Germany Rearms

In January 1934, Hitler began his appease-and-attack campaign by signing a ten-year nonaggression pact with Poland, which boasted an army far larger than Germany’s. This allowed Hitler to appear as a peacemaker while giving him time to secretly rearm his nation.

Later that year, Hitler visited Mussolini—one of his idols—for the first time, but the meeting didn’t go well. Mussolini didn’t particularly care for Hitler (he thought the German leader was mad and referred to him as a buffoon behind his back), and the two dictators parted without agreeing to anything significant. Soon after, Hitler angered Mussolini further with a failed attempt to place a puppet regime in Austria after the assassination by Viennese Nazis of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, who was one of Mussolini’s most valued allies. However, Hitler was able to publicly and successfully disavow his role in Dollfuss’s killing—even though he was a primary instigator— and continued to court Mussolini as an ally. Two years later, the two men formed the Rome-Berlin Axis, which set the stage for war in Europe.

Hitler Takes Austria

With Mussolini now his ally, Hitler put into play his plan to annex Austria. In 1936, he had tried to placate Mussolini, who was then Austria’s protector, by signing an agreement recognizing the nation’s sovereignty. In return, Hitler had forced Austrian chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg to declare his nation a German state and promise to share power with the national opposition. These provisions legitimized the Austrian Nazis who advocated reunification with Germany and laid the foundation for Hitler’s takeover of the nation two years later.

The groundwork for the planned takeover began in February 1938 when Schuschnigg traveled to Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s mountain retreat, to complain about a Nazi coup being planned against him. Hitler was far from sympathetic. With Schuschnigg on his turf, Hitler took the opportunity to browbeat him into signing a pledge to give moral, diplomatic, and press support to Germany; to stop prosecuting Nazi agitators; and to appoint a Naziaffiliated lawyer named Artur Seyss-Inquart as interior minister. A frightened Schuschnigg signed the demands. He quickly recovered after his return to Austria, however, and called for a plebiscite, or popular vote, to determine the people’s wishes on Austrian independence. Then, Schuschnigg tried to exclude many Nazi sympathizers by limiting voting to those over the age of twenty-four.

Hitler became furious at Schuschnigg’s attempts to prevent reunification. Hermann Goering, whom Hitler had ordered to handle the matter, demanded that the vote be postponed, and Schuschnigg agreed. Goering then demanded Schuschnigg’s resignation, which he tendered. But when Goering demanded that Seyss-Inquart be made chancellor, Austrian president Wilhelm Milas refused. On March 12, Hitler ordered his troops into Austria. The occupation was met with little resistance because Schuschnigg urged the army to stand down. Despite his efforts to avert a military confrontation, Schuschnigg was arrested and spent seven years in prison.

Hitler followed his troops into Austria and was met with nearly nationwide adoration. As a result of Hitler’s mesmerizing oratory, most Austrians had become convinced that reunification with Germany was the only way to reclaim their lost greatness. Unfortunately, it was also the end of any sort of democratic rule. With Hitler firmly in place as the nation’s leader, anti-Nazi dissidents were brutally punished and Jews were sent into exile or to concentration camps.

Kristallnacht—the Night of Broken Glass—refers to the attacks on Jews in Germany and German-controlled territories on November 9, 1938. Over the course of the night, SA and SS units burned more than 200 synagogues, destroyed nearly 7,500 Jewish-owned businesses, and attacked any Jew they encountered. More than 200 Jews were killed, 600 were seriously injured, and approximately 30,000 were arrested.

These early years of German expansion also marked the beginnings of the “Final Solution,” Hitler’s plan to eliminate as many Jews as humanly possible on the theory that they were to blame for the country’s ills. Kristallnacht was followed by a host of other terrible nights and days and weeks and years for Jewish and other “undesirables” in Germany and the countries absorbed by the Third Reich. The Jewish people, especially, were systematically, efficiently, and ruthlessly singled out, transported, and murdered in unimaginable ways. Deportations led to incarcerations led to forced labor led to mass killings. All of this was hidden behind a veneer of political expansion and military threat. The lebensraum that Hitler so publicly pined for—and got, in the Sudetenland and in Austria—didn’t include space for Jews.

Despite the obvious force used by Germany to take over Austria, both the United States and Great Britain accepted Hitler’s conquest. Italy also accepted the situation, sending congratulations to Hitler. “Tell Mussolini I will never forget him for this,” Hitler told Il Duce’s emissary. “Never, never, never, whatever happens.”

The Nazis then ordered another carefully orchestrated plebiscite on the issue of reunification. More than 99 percent of Austrians approved the takeover.

The conquest of Austria—and other nations’ unwillingness to confront him on it—gave Hitler the confidence he needed to pursue his dream of world domination, which he saw as Germany’s divine right. On August 22, 1939, he made a speech to the German High Command in which he outlined his plan for the swift and brutal invasion of Poland, a nation he had lulled into complacency with a meaningless nonaggression pact.

Czechoslovakia Divided and Conquered

The stage for Hitler’s invasion had been set earlier in the year with the dissection of Czechoslovakia. The previous year’s Munich Conference, which was thought to have brought “peace in our time,” had given parts of the country to Germany. Then Poland and Hungary received their shares as well. What remained of Czechoslovakia turned into a federation of three republics. Then, in March 1939, Slovakia seceded to become an independent state, though still under German domination.

The Czech Republic was the last prewar domino to fall before Hitler. President Emil Hacha tried desperately to appease Germany by enacting anti-Semitic and anti-Communist laws, but it didn’t help. The Wehrmacht, Germany’s armed forces, began gathering troops at the Czech border. On March 14, the day Slovakia declared its independence, Hacha traveled to Berlin to beg for his nation’s very existence. Hitler met with Hacha and his aides at 1:15 A.M., told them the invasion would begin at 6:00 A.M., and then stormed out of the room. German cabinet ministers Hermann Goering and Joachim von Ribbentrop told Hacha that Prague would be bombed to rubble if he didn’t sign surrender documents immediately. Hacha, who suffered from a heart condition, passed out when he heard the demand but was revived by one of Hitler’s doctors long enough to sign the document that effectively gave his country to the Nazis.

When he received the signed surrender, Hitler hugged Goering and Ribbentrop, shouting, “Children! This is the greatest day of my life!” That evening, he rode with his troops into Prague. Hacha remained in power as a puppet president of the new German protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

France and Great Britain knew of Hitler’s intentions long before his troops crossed the Czech border but hoped they could placate the mad dictator and avoid a confrontation. At a conference in Munich in September 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Premier Edouard Daladier met with Hitler to work out a peace deal. Chamberlain and Daladier agreed to let Germany take the Sudetenland, a German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia. Hitler promised to leave the rest of Czechoslovakia and the rest of Europe alone, and Chamberlain and Daladier wrote out a pledge of friendship among the nations, which Hitler signed with absolutely no intent of honoring.

Shortly after annexing Czechoslovakia, Hitler demanded the return of the former German port of Memel, which was then part of Lithuania. His demand met with little resistance.

World war became a near certainty on March 31, 1939, when Great Britain and France, embarrassed by Hitler’s successful manipulation of their mutual promises, guaranteed aid and assistance to Poland and Romania if Hitler acted against them. To Hitler, England and France— once two of the most powerful nations in the world—were mere gnats buzzing about his head and offered little to fear.

Hitler’s remarkable success at snatching nearby countries without rebuke emboldened Mussolini, who was eager to extend his new Roman Empire. Mobilizing his army, he quickly conquered nearby Albania. Shortly after Italy conquered Albania, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a cable to Mussolini and Hitler asking the dictators to promise that they would rein in their armies for at least twenty-five years. As might be expected, both men saw the cable as a sign of weakness.

Mussolini didn’t like Hitler, but he admired the fact that Hitler was able to take Czechoslovakia without firing a single shot. In 1939, the two countries signed an alliance that came to be known as the Pact of Steel. Although most people didn’t know it at the time, the alliance would soon pit the two daring dictators against the rest of the world.

Figure 2-1 Hitler and Mussolini in Munich, circa June 1940.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (242-EB-7-38)

Hitler Pushes East

Hitler’s next move—the bold invasion of Poland—was the final stroke that ignited World War II. In the days following his speech to the German High Command, there was much diplomatic discussion as Hitler tried to overcome British opposition to his plans. Chamberlain had announced that if Poland’s sovereignty were threatened, the British would “feel themselves bound at once to lend the Polish government all support at their power.” Mussolini was also bothered by Germany’s planned aggression, and he strongly encouraged Hitler to continue negotiating with Poland rather than invade it. But Hitler refused to listen, and on August 31 he ordered his troops across the border. At the same time, he ordered that all terminally ill patients in German hospitals be euthanized to make room for the anticipated wounded.

Polish leaders had long believed that if Germany did attack, the Soviet Union would respond swiftly with troops. After all, Germany and the Soviet Union had been at odds ever since taking opposite sides in the Spanish Civil War. However, Hitler had cleverly eliminated any Soviet threat by signing a nonaggression pact with Stalin on August 23, 1939. As history would show, this pact was as meaningless to Hitler as the one he had signed with Poland.

Figure 2-2 Soviet commissar Vyacheslav Molotov signing the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (242-JRPE-44)

To give Hitler an excuse for his invasion, SS chief Heinrich Himmler concocted the story that Polish soldiers had attacked a German radio station in the border town of Gliwice. An unnamed prisoner was taken from a German concentration camp, placed in a Polish uniform, and shot by the Gestapo (the secret state police) outside the radio station. It was all Hitler needed to put his plan into motion.

Poland Is Brought to Its Knees

Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, with a brutally fast attack known as a blitzkrieg (a combination of two German words meaning “lightning war”) in which the enemy is hit with ruthless speed and efficiency with multiple methods of attack in an effort to destroy it before an effective defense can be mounted. This was in extreme contrast to the trench warfare of World War I, in which enemy armies dug in at fixed positions and then slugged it out.

The blitzkrieg against Poland was devastating. Even though Poland had a larger army, sudden air attacks destroyed much of its air force while it was still on the ground; then another wave of bombers took out the nation’s roads and railways, assembly points, and munitions dumps and factories. German planes also attacked numerous civilian centers, causing extraordinary panic.

Figure 2-3 German troops parading through Warsaw, September 1939.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (200-SFF-52)

German dive-bombers then attacked marching troops without mercy in an attempt to decimate enemy forces and demoralize anyone who was left. Civilian refugees were strafed with machine gun fire as they fled the approaching troops, causing still more chaos on Poland’s already crowded roads and hindering Polish troops. Within a matter of hours, Hitler’s troops brought Poland to its knees.

While the Luftwaffe rained bombs on Polish soldiers and civilians alike, wave after wave of motorized infantry, light tanks, and motor-drawn artillery poured into the country, followed by heavy tanks, doing as much damage as possible as they plunged deep into Poland. Once a region had been softened up with air attacks and artillery, it was occupied by German foot soldiers supported by artillery, who mopped up whatever resistance remained. More than 2 million German civilians living in Poland aided the German army by giving precise information on Polish troop movements.

Hitler’s invasion of Poland had two goals: to regain territory lost after World War I and to impose German rule over the rest of the country. To this end, he almost immediately began a campaign to eradicate both enemies of Nazism and those he considered inferior, particularly Poland’s large Jewish population. Numerous atrocities were committed in the weeks following the German invasion, including massacres of hundreds of unarmed military personnel and civilians, destruction of entire villages, and incarceration or murder of anyone who voiced any type of opposition against the new leadership. Hitler’s army was a merciless iron hand held at the throat of the Polish people and its government, and it tightened its grip with each passing day.

Hitler’s blitzkrieg succeeded beyond his wildest hopes. The Polish government was forced into exile, and of the nation’s 1 million soldiers, 700,000 were taken prisoner and another 80,000 fled the country. Germany’s expeditionary force of 1.5 million soldiers suffered minimally— just 45,000 dead, wounded, or missing.

Sixteen days after Germany invaded Poland, the Soviet Union sent troops into eastern Poland, supposedly to assist the Ukrainians and Belorussians who lived there. In reality, this action was part of a secret agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union to divide Poland among them, and it dealt the deathblow to Poland’s struggle. On September 28— the day after a heavily battered Warsaw finally fell—Germany and the Soviet Union signed a pact that divided Poland in two, with the eastern half going to the Soviet Union and the western half going to Germany. Hitler also conceded the Baltic States and Finland to the Soviet sphere of influence.

The Role of Finland

Finland’s role in World War II can appear a little confusing as a result of its ongoing conflict with the Soviet Union. The nation was freed from Russian rule following the Bolshevik Revolution, but the relationship between the two nations remained tense. In early 1939, as Finland and Sweden were negotiating the fortification of some islands they shared in the Gulf of Bothnia, the Soviet Union began harassing Finland. In August, the secret pact between Germany and the Soviet Union placed Finland and the Baltic nations under the USSR’s sphere of influence, and the Soviets began planning the conquest of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Relations between Finland and the Soviet Union continued to deteriorate, and on November 30, 1939, after claiming that Finnish soldiers had fired on Soviet troops, the Red Army attacked—only to be beaten back. The Soviets regrouped and attacked again early in 1940. Finland fought valiantly but faced overwhelming odds, so it reopened negotiations with the USSR and, in return for peace, lost the Karelian Isthmus and other territory along the border.

Late in 1940, Finland—technically neutral in the war but still anti-Soviet—allowed German troops to pass through from Soviet territory for the German occupation of Norway. When Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, Finland joined in. As a result, the nation was considered an Axis power by the United Kingdom, which declared war on Finland on December 6, 1941.

Great Britain and France declared war on Germany two days after Hitler invaded Poland. Those declarations of war included a blockage of German ports, which was initially very successful at denying Germany needed raw materials, especially food. Hitler asked the two nations to rescind their declarations and promised to leave the surrounding nations alone. This time, Great Britain and France refused to budge. The standoff would continue until Hitler’s attack on Denmark and Norway in April 1940.

Hitler Takes Denmark and Norway

As the smoke cleared over a vanquished Poland, an uneasy calm settled on Europe. Great Britain and France were both engaged in a sea war with Germany (an ongoing conflict that became known as the Battle of the Atlantic), but there was no war on land—at least for a while.

Hitler next turned Germany’s military might against Norway and Denmark. The reason was simple: Germany needed to safeguard important iron ore shipments arriving mostly from neutral Sweden and to give its navy a safe passage through Norwegian coastal waters into the North Atlantic. Taking the Scandinavian peninsula would also provide Germany with much-needed food and other goods that were in short supply as a result of the British-French blockade of German ports.

The invasion of Norway and Denmark was placed in the hands of the German navy. Naval forces were to land along the Norwegian coast on April 9, 1940, while airborne units were dropped on Norway and Denmark to capture essential airfields.

Norway, which tried to remain neutral during Hitler’s grab for land, learned of the planned invasion a day before it was to occur when Norwegians in Kristiansund picked up 122 survivors from a German transport that had been torpedoed by a Polish submarine. The captured Germans admitted that they were part of a planned invasion force, but, incredibly, the Norwegian cabinet did nothing to set up defenses.

Others, however, were doing what they could to halt Germany’s aggression. Great Britain defied international law by laying mines in Norwegian waters to slow the iron ore trade between Germany and Norway. It was initially believed that when Germany invaded Denmark and Norway on April 9, it was in response to this British mining of Norwegian waters. However, the attack had been planned for two months.

Once again, the blitzkrieg offense proved devastatingly effective. It took Germany just four hours to invade and conquer Denmark. German troops marched across the Danish border early on the morning of April 9, overwhelming the surprised Danes into surrendering. At the same time, German troops emerged from cargo ships in Norwegian ports, and aircraft dropped German paratroopers onto Norwegian airfields. Simultaneously, German destroyers, protected by thick fog, moved up Norway’s main fjords to unload additional troops and provide artillery support to the assault.

Caught somewhat by surprise, the Norwegians fought with all they had, assisted by British troops and planes, but the German army was far too powerful. Despite their heroic efforts, the Norwegian soldiers never really had a chance.

The accompanying sea battle, however, went a little differently. The first German losses were at the hands of Norwegian defenders at Oslo Fjord, who opened fire from coastal defense batteries at close range. On the first morning of the sea war, the heavy cruiser Blücher was sunk with the loss of several hundred troops and civilians who were to act as occupation officials. Two other coastal defense ships managed to damage another German cruiser, and gunners at Oslo Fjord took out a German torpedo boat.

Germany’s use of paratroopers during the 1940 blitzkrieg invasion of Norway was the first ever in war. The largest mass drop of the war was Operation Varsity on March 24, 1945. In that remarkable effort, 1,285 transports and 2,290 gliders were used to lift more than 9,300 U.S. paratroopers and 4,976 British troops across the Rhine. Bombers followed, dropping supplies.

British destroyer guns and British naval aircraft flying from the Orkney Islands also managed to inflict heavy damage on the invading German forces, sinking a light cruiser and ten destroyers. The battleships Scharn-horst and Gneisenau were also damaged during the battle, which continued into June. British and French naval losses included the sinking of several destroyers and the aircraft carrier Glorious.

By late May, the British and French troops had established strong positions near Narvik (Norway), but the military collapse the Allies were facing in northern France and the Low Countries forced them to abandon the Norwegian campaign. During the first week of June, the Allies were able to evacuate 27,000 people with almost no losses, as well as King Haakon and the officials who would quickly establish Norway’s government in exile.

It took two months, but Norway and Denmark now belonged to Hitler. However, the conquest had a downside for Germany. More than 300,000 troops had to be stationed in Norway, which kept them far from battle, and their presence did little to quell seething anti-German resistance.

The Fall of France

The German blitzkrieg into Norway and Denmark foreshadowed what lay ahead for France, which had joined forces with Great Britain to try to halt Hitler’s conquest of Europe. Internally, France was going through a political shift. Communist organizations were dissolved, and a vote of no-confidence resulted in new leadership as Daladier stepped down to become minister for the war and Paul Reynaud was selected to be premier.

Things happened quickly in Europe from May to July of 1940. Germany simultaneously invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, taking the three countries with remarkable swiftness. French and British troops tried to halt the German invasion but found themselves overwhelmed and forced to retreat. On May 13, German troops established a bridgehead at Sedan, the gateway to France; the nation, which had been invaded by Germany during World War I, again found itself fighting for its existence.

Breaking through the French border defenses took just two days. German forces outflanked the famed Maginot line—a defensive perimeter of forts along the French-German border—and raced through the Ardennes. Almost immediately, France found itself an occupied country. British prime minister Winston Churchill learned of France’s fate when he received a telephone call from Premier Reynaud who, speaking in English, said simply: “We have been defeated.”

On June 10, the French government fled Paris, first to Tours and then, on June 14, to Bordeaux. Two days later, Reynaud resigned as premier and his successor, Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, surrendered the French army. Germany and France signed an armistice on June 22, and two days later, General Charles de Gaulle, who had fled to Great Britain before the German army had invaded, was recognized by the British government as the leader of the Free French.

As the war drew to a close, French Resistance leaders executed an estimated 10,000 French collaborators. Thousands more were sent to jail.

France Carved Up

Germany claimed the Alsace-Lorraine area of France, long a point of contention in previous wars, as a territory and occupied northern and western France as a conquered land, putting it under the military governor of Belgium. The remainder of France was left unoccupied and was administered, along with all French colonies, by a collaborationist government that became known as Vichy France because its capital was the city of Vichy, approximately 200 miles southeast of Paris.

Intent on punishing France for its role in humiliating Germany with the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles as well as for transgressions in previous wars, Germany fined France an estimated $120 million and assessed occupation costs of nearly $2 billion a year. In addition, the Bank of France was forced to extend huge credits to Germany. These figures were as staggering as those imposed on Germany by France and its allies at the end of World War I.

Worst of all, however, according to many, was the plunder of France’s priceless artwork. A total of 140 railcars of looted art—including irreplaceable works by many of the world’s great masters—were taken from France to Germany. Hitler, himself a failed painter, coveted great works of art and thought that his nation, which he considered to be the strongest on the planet, had a right to inherit the legacy of such masterpieces.

The German invaders found life in France much to their liking, at least for the first few years. The best wines were reserved for high-ranking German officials, as were specially designated seats on all public transportation. Many Germans also enjoyed the company of French women who found it easier to join their nation’s conquerors than to resist them. (After the liberation of France, many such women, loathed by their countrymen, were forced to parade through town with their heads shaved as a sign that they had been Nazi sympathizers.)

A strong French underground resistance sprang up almost overnight, but the price for its activities was high: 100 French hostages killed for every German. Nonetheless, the underground succeeded in hindering the Nazi war effort through sabotage and guerrilla warfare.

Figure 2-4 A French woman who had collaborated with the Germans during the occupation has her head shaved.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (111-SC-193785)

Operation Dynamo

The war could have ended for the Allies with the fall of France, if not for the astounding evacuation of nearly 300,000 troops from the French port of Dunkirk.

The German advance, which had been lightning-swift, trapped nearly 200,000 Britons and 140,000 French and Belgians in the coastal city near Belgium. To save them, the British Admiralty rounded up virtually every seaworthy vessel available—from warships to tiny pleasure craft. On May 26, the first vessels sailed across the English Channel, protected by Royal Air Force planes, and the waiting soldiers crowded the beaches and piers to greet them.

The evacuation, code-named Operation Dynamo, lasted ten frightening days. British and French destroyers raced to the port, took on as many soldiers as they could, then, with guns firing almost constantly, raced back to Dover, England. Smaller boats carried troops to ships located outside the ruined Dunkirk harbor. Hitler, who certainly had enough troops and tanks in the country to prevent such a thing, had misread the situation and halted his advance too soon to prevent this massive relocation of troops. Instead the Luftwaffe was sent to do what damage it could.

The horrors and hazards of the evacuation—the largest of its kind in history—were tremendous. German planes rained a constant barrage of bombs on both land and sea, terrorizing those still waiting for rescue. The Royal Air Force (RAF) engaged the Germans at every opportunity, downing 159 enemy planes (which was significant but not too threatening, since the Luftwaffe possessed many more planes and the capacity to manufacture a great many more). Making things worse was the knowledge that every hour brought the invading German army closer and closer. Three days into the evacuation, the nearby port of Calais fell to the Nazis, and the following day Belgium surrendered. The situation might have ended far worse if Hitler had not twice suspended his drive toward Dunkirk to concentrate on other objectives.

When the rescue was over, only 2,000 had died. Those who made it to the Dover shore were greeted with cheers and soon left to continue the fight against Germany.

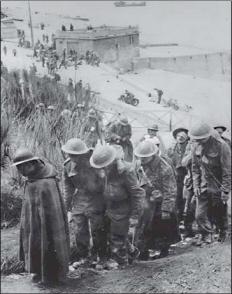

Figure 2-5 British prisoners at Dunkirk.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (242-EB-7-35)

In the United States, there was a sense of shock as France fell to the Nazis, leaving an ill-prepared Great Britain to fight alone. While the United States remained neutral regarding affairs in Europe, Congress decided to prepare for the worst by enacting the first peacetime conscription in American history and greatly increasing the military budget. However, the public, while sympathetic toward Great Britain’s plight, was not eager to engage Germany, and most Americans maintained that isolationism was still the best policy.

Mussolini Joins the Fray

Benito Mussolini watched with awe as Hitler’s troops stormed across Europe. He desperately wanted to join in, fearful that there would be little left to conquer once Hitler was finished, but several factors prevented him from acting immediately. Foremost, his people weren’t in the mood for war and conquest, preferring to enjoy a more pacifistic lifestyle. Moreover, his army was ill-prepared to enter a major war. Mussolini was also angered by Hitler’s pact with Stalin and his vicious treatment of Poland, which had taken even Mussolini by surprise and made him think twice about joining forces with such a tyrannical leader. In the back of Mussolini’s mind was the thought of what would happen if Germany lost the war.

However, Mussolini’s grand ego and Hitler’s strong urging eventually overcame any doubts Mussolini may have had about bringing his nation into what was obviously gearing up to be a full-blown world war. In March 1940, the two dictators met at the Brenner Pass on the Austrian-Italian border to formalize their alliance. During the meeting, Mussolini promised to commit his troops the moment Germany’s attack on France appeared successful.

Italy Declares War, Begins Blunder

That moment came sooner than expected. On June 10, as France fell to the Nazis, Benito Mussolini declared war on Great Britain and France with the statement: “This is the struggle of the peoples who are poor and eager to work against the greedy who hold a ruthless monopoly of all the wealth and gold of the earth.”

Though personally doubtful of his own army’s chances of success, Mussolini had boasted to Hitler of Italy’s military might. Appointing himself the new commander of Italian armed forces, Mussolini ordered his troops to attack France from across the Alps. The results were far less than Mussolini— or Hitler—had expected. Italy’s first assault on southern France resulted in the acquisition of very little territory, as Italian troops were pushed back by the smaller but better prepared French forces.

The other battles in which Italy engaged were equally unimpressive. An August invasion of British Somaliland by 40,000 Italian troops succeeded only because the Italians outnumbered the British four to one. And even then, Italy lost 2,000 men to Britain’s 260, and the engagement took a full two weeks. In September, 80,000 Italian soldiers marched from Libya into Egypt, heading for the Suez Canal. They faced just 30,000 British troops— and were driven back, losing much of eastern Libya in the process.

In October, without consulting Hitler, Mussolini sent 155,000 troops into Greece from Albania. And once again, the Italian army failed to win. Worse, a third of Albania fell into Greek possession, while the British landed on the strategically important island of Crete.

Mussolini was supposed to be waging a parallel war in the Mediterranean while the Germans took control of northern Europe, but such was not the case. There were no devastating Italian blitzkriegs, just a mishmash of battles fought by poorly trained and ill-prepared Italian troops who wished they were anywhere but on the frontlines of a war. As a result, Hitler came to view Mussolini more as a hindrance than an ally and spent much time cleaning up Mussolini’s messes.

The Axis Expands

In November 1940, Hitler brought Romania and Hungary into the Axis alliance, primarily because he needed to cross them to get to Greece and, later, the Soviet Union. Bulgaria joined in March 1941. Yugoslavia, however, refused to follow, so Hitler ordered an invasion, which began on April 6, 1941.

The invasion of Yugoslavia was a tough conquest, with German military officials having to pull together an army of nine divisions from Germany and France in less than ten days.

On April 10, German forces began attacks on Belgrade from the northwest, north, and southeast. The city fell three days later, quickly followed by the surrender of the Yugoslav army. Like many other conquered countries, however, Yugoslavia proved more difficult to hold than it had been to take. Guerrilla fighters would continue to harass the Nazi invaders over the course of the war.

Next, Hitler went after Greece, which was better prepared to fight than Yugoslavia had been. Its fighting force of 430,000 men was fully mobilized and battle-tested, but things went poorly from the start. The Greeks’ efforts to defend the Metaxas line northeast of Salonika proved to be a disaster, and German troops forced the surrender of the line and nearly half the Greek army on April 9. Almost two weeks later, the Greek First Army was attempting to pull out of Albania but became trapped at the Metsovon Pass and was forced to surrender.

The German drive accelerated after that, with the Nazis taking the Isthmus of Corinth by April 27 and the Peloponnesus by April 30, forcing British defenders into an evacuation that cost nearly 12,000 men. In addition, a week-long airborne assault in late May brought Crete under German control.

As all this was going on, German general Erwin Rommel had launched a very successful counteroffensive against the British in Libya, pushing them from the country with the exception of an isolated garrison at Tobruk. North Africa was quickly falling into German hands.

Japan Extends Its Military Might

The Japanese leadership watched the events in Europe closely in 1939 and 1940 and found in Germany’s rapid victories the encouragement it needed to expand its control into Southeast Asia. The expansion was necessary to meet Japan’s desperate need for natural resources such as petroleum and rubber to help carry on its military efforts against China and elsewhere.

Its reliance on supplies from other countries was a major problem for Japan. As a result of a commercial treaty signed in 1911, a high percentage of Japan’s resources came from the United States, including oil (66 percent), aviation fuel (100 percent), metal scrap (90 percent), and copper (91 percent). But in July 1939, President Roosevelt, angered by Japan’s growing militarism, threatened to terminate the treaty and sever this essential source of supplies. Realizing that it could no longer rely on the United States for resources, Japan began to hungrily eye its neighbors.

The descent into war in the Pacific began to accelerate. When France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands finally fell to the Germans, the government of Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe announced Japan’s plan to create a self-sufficient economic and political coalition under Japanese leadership to be known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which would dramatically change the balance of power in the Pacific because the defeated European nations had ruled much of southeastern Asia as colonies.

Then, in September 1940, the Konoe cabinet joined the Axis by signing the Tripartite Pact. In so doing, Japan received permission from Germany to occupy French Indochina, which had been a source of supplies for China. In Indochina, Japan would be able to establish bases it could use to conquer nearby regions rich in the natural resources it so desperately needed. Of special interest to the Japanese were the Pacific colonial territories of the Netherlands and Great Britain, particularly the oil-rich Dutch East Indies.

Meanwhile, relations between Japan and the United States continued to worsen. After a series of shakeups, the Japanese cabinet hardened its expansionist policies. The message was clear: Japan needed land and resources and was more than willing to take them by force. On April 13, 1941, Japan and the Soviet Union signed a neutrality pact that greatly benefited both countries. The Soviet Union agreed to respect the borders of the puppet state of Manchukuo, and Japan pledged to do the same in Mongolia. The pact gave Japan important protection on its Soviet flank and opened the door for war against the United States and the European colonial powers.

Japanese militarists wasted little time. In July 1941, after removing the remaining moderates, the military-dominated Japanese cabinet ordered an invasion of the rest of Indochina and demanded more conscripts. U.S. President Roosevelt responded to Japan’s increasingly warlike attitude by freezing all Japanese assets in the United States and cutting off oil exports to Japan. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe struggled for a diplomatic solution, but the armed forces favored a more militant policy and urged at a conference in October that the nation prepare itself for war.

Konoe resigned as prime minister and was replaced by General Hideki Tojo, Japan’s minister of war. Tojo, a career military man, drew a line in the sand when he demanded that the United States cease sending aid to China, accept the Japanese conquest of Indochina, resume normal trade relations, and not reinforce American bases in the Far East.

Negotiations between Japan, represented by Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura, and the United States, represented by Secretary of State Cordell Hull, quickly hit an impasse. On November 26, the United States again demanded that Japan withdraw from China and Indochina if negotiations were to continue, but Japan wasn’t about to give back what it had already taken. Considering Hull’s demand an ultimatum and thus seeing no need for further talks, Tojo ordered to sea a Japanese task force that had been assembled secretly off the island of Etorofu. Its target: the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor.