The Attack on Pearl Harbor

Military intelligence in Washington, D.C., had intercepted a series of memoranda from Tokyo indicating that the Japanese were planning some kind of aggressive action. The messages were delivered to President Roosevelt that evening, but he took no action. He believed that war with Japan was imminent but that the Japanese would never attack American soil, preferring instead to push farther into Asia.

On the morning of December 7, what was thought to be the last of the fourteen communiqués from Tokyo was intercepted and decoded. It noted that Japan was breaking off all negotiations with the United States. The message was delivered to President Roosevelt at 10:00 A.M. EST, but again, he saw no cause for immediate concern. Then another message was intercepted, this one instructing Ambassador Saburo Kurusu to present the Japanese reply at exactly 1:00 P.M. EST, or 7:30 A.M. Pearl Harbor time. If everything went as planned, that would be the exact moment Japanese bombers would be over Pearl Harbor.

An astute naval officer immediately understood the significance of Japan’s timing and arranged to have General George Marshall, who had been enjoying a horseback ride along the Potomac, brought to the War Department for consultation. Marshall also understood the significance of the final Japanese memorandum, but his message of warning to Pearl Harbor could not be delivered immediately because the department was not in radio contact with Honolulu. Instead, the message went by commercial wire and radio and was not received until 7:33 A.M. Pearl Harbor time. The bicycle messenger sent to deliver the warning was furiously pedaling to Fort Shafter when, at 7:55 A.M., destruction came raining down from the sky.

All Hell Breaks Loose

The first wave of Japanese bombers and attack planes consisted of forty torpedo bombers (known as Kates), fifty-one Val dive-bombers, and approximately forty-nine high-level bombers escorted by forty-three Zero fighters. The torpedo bombers came in low to drop their destructive torpedoes while the Vals dropped bombs and armor-piercing shells on the docked ships below. At the same time, the Zeroes dropped bombs on American planes in the airfields, a move designed to thwart saboteurs; no thought had been given to an enemy air attack.

The massive ships along Battleship Row never stood a chance. The first to go down was the Oklahoma, its hull ripped open by three torpedoes, and the deathblow delivered by two more. Panicked sailors screamed for their lives as the ship exploded and began to sink. The crew of the Maryland, which was moored next to the Oklahoma, used the smoke and burning wreckage of their sister ship as protection while they fought the surprise attackers with everything they could find. Astoundingly, the Maryland survived the two bombs that struck it.

Figure 3-1 The USS Shaw exploding during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-16871)

While Japanese planes screamed overhead and bombs exploded all around, the sailors on the ships along Battleship Row used axes and hammers to open the locked boxes containing the ammunition they needed to fight back. With the first explosions ringing over the island, sailors on shore leave raced back to their ships, even swimming when necessary.

The other moored battleships, unable to maneuver, also proved easy targets for the attacking Japanese planes. The West Virginia went down after being hit with two bombs and several torpedoes; its hulk provided protection for the Tennessee, which escaped most of the torpedoes aimed at it but was set afire by flaming debris from the Arizona moored behind it. The Arizona was hit so hard by the Japanese that it sank in minutes, taking more than 1,100 crewmen with it, including Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, commander of Battleship Division One, and the ship’s commanding officer, Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh. The California, which was moored alone, exploded in a fireball that reached 500 feet into the sky when a bomb struck its arsenal.

The only battleship to attempt to get out to sea was the Nevada, which was also moored alone. Its frantic crew engaged in a grueling battle with Japanese planes before finally being forced aground. The crew of the Pennsylvania, which was in dry dock at the time, fought valiantly, blanketing the air with so much antiaircraft fire that the ship took only one bomb hit.

The Japanese had sent two waves of attack planes against Pearl Harbor (a third wave was waiting and ready but was not called into action), intent on inflicting as much damage as possible in the hope of permanently crippling the American military presence in the Pacific. By midmorning, as the last Japanese planes headed back to Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s carrier fleet, four U.S. battleships had been sunk and four had been severely damaged. In addition, three light cruisers, three destroyers, and four smaller vessels were also destroyed or severely damaged. All but three of the sunken ships were raised and returned to action. The military decided to leave the Arizona where it went down and later turned the site into a solemn memorial to the military personnel and civilians who died during the assault.

Land Targets

The nearby airfields also suffered tremendous damage. Dozens of planes, parked wingtip to wingtip, made an easy and vulnerable target for Japanese bombers. In the end, only a handful of American fighters managed to make it into the air to engage the enemy attackers.

At Hickam and other area airfields, 188 aircraft—75 percent of the island’s military air fleet—had been destroyed before they could take to the air. Luckily, the fleet’s three aircraft carriers—the primary target of the Japanese attack—were out to sea on maneuvers and escaped harm. Human casualties were also high: 2,403 servicemen and civilians killed and another 1,104 wounded. Most of the casualties were aboard the destroyed ships, though a direct hit on the mess hall at Hickam Field killed 35.

American forces did manage to inflict some damage on the attacking Japanese, downing twenty-seven planes and killing sixty-four airmen and seamen. In addition, the Japanese lost five two-man midget submarines, which had been deployed to penetrate the harbor minutes before the attack.

A Well-Planned Attack

The attack on Pearl Harbor was anything but a last-minute decision by the Japanese military. In truth, the assault was more than a year in the planning, and was under way even as the Japanese government went through the motions of negotiating with the United States regarding Japan’s ongoing aggression in the Pacific.

The mastermind behind the attack on Pearl Harbor was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Yamamoto began planning the attack in November 1940, just two months after signing the Tripartite Pact, which brought Japan into the Axis with Germany and Italy.

It is commonly believed that Yamamoto had two sources of inspiration for the attack on Pearl Harbor. The first was a 1925 book titled The Great Pacific War by Hector Bywater, a British naval expert. Bywater’s book realistically describes a war between the United States and Japan that begins with the destruction of the Pacific Fleet and a Japanese invasion of the Philippines and Guam. The second source was the November 1940 RAF strike at Taranto, Italy, in which torpedoes heavily damaged two Italian battleships. The event impressed Yamamoto because it was the first practical attack by aircraft on battleships.

In January 1941, Yamamoto instructed Rear Admiral Takijiro Onishi, a renowned naval aviator, to prepare a preliminary study on the feasibility of an attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. The plan was completed in April and called for Japan to make a surprise air and submarine attack on Pearl Harbor. The site was selected because it was both a major U.S. military installation and close enough for Japanese forces to approach with little risk of detection.

Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, director of the air attack, spent the next several months developing the tactics and equipment necessary to fly to Hawaii and take out the ships along Battleship Row. In November, after the Japanese government approved the attack, it became known as the “Hawaiian Operation.”

On November 30, the Japanese cabinet set December 7 as the date Japan would declare war on the United States. On December 1, Yamamoto’s flagship in Japan’s Inland Sea sent out a prearranged coded message—“Climb Mount Niitaka”—which was the signal to attack Pearl Harbor on Sunday, December 7.

The first U.S. prisoner of war was Ensign Kazua Sakamaki, the sole surviving crewman of the five Japanese midget subs destroyed by American forces during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Victory Breeds Confidence

Pearl Harbor was not the only target of the Japanese on that fateful day. Simultaneously, Japanese planes attacked the British in Malaya and Hong Kong and American military bases in the Philippines, Guam, Midway, and Wake Island. The barrage caught everyone by surprise, and there was little time to mount a defense. Within twenty-four hours, a huge expanse of the Pacific belonged to Japan.

Yamamoto and Tojo both believed the war was over at that point, confident that the United States and Great Britain had been weakened to the point where they could not and would not fight back. Hitler, too, believed that the United States would not pursue war, telling his aides, “Now it is impossible for us to lose the war. We now have an ally who has not been vanquished in 3,000 years.”

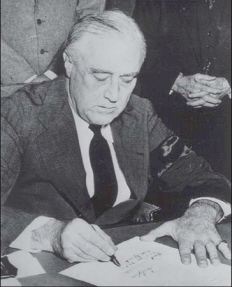

Figure 3-2 Roosevelt signing the Declaration of War against Japan the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (79-AR82)

Lulled by America’s earlier neutral stance and now believing the nation to be weak and essentially defenseless, Hitler declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941. Italy followed suit shortly after. But rather than rolling over as anticipated, the United States reacted almost immediately with its own declarations of war against Germany and Italy, while Great Britain declared war on Japan.

Pearl Harbor Investigations

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor sparked a flurry of questions, the most obvious being “How could it have happened?” Despite a worldwide intelligence and surveillance network and a meticulously trained home guard, the United States could not prevent Japan from sneaking up and delivering a devastating blow. In the years following the attack, eight major investigations would attempt to answer the question of how it had happened.

The first investigation was a closed-door board of inquiry ordered by President Roosevelt eleven days after the attack. The Roberts Commission, named after its chairman, Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, concluded its investigation January 23, 1942, by laying the blame on Admiral Husband Kimmel, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, commanding officer of the U.S. Army’s Hawaiian Department. In its official report, the Roberts Commission declared that the two men had failed to exhibit the qualities of high command. Kimmel and Short had been relieved of duty by the time the commission concluded its investigation, and both men soon retired.

Six more closed-door investigations were conducted by the U.S. Army or Navy over the next few years, their results cloaked in secrecy because of concerns over military security. It wasn’t until after the war that the public would learn exactly what had happened on December 7, 1941.

Congressional Investigations

November 15, 1945, saw the beginning of a joint congressional investigation into the disaster. It lasted six months and produced more than 15,000 pages of testimony. Both the majority and minority reports issued at the end of the investigation placed the primary blame on Kimmel and Short, noting that the two men had failed to heed warnings from Washington of a potential enemy attack and that they had failed to properly alert their forces. The committee concluded that while Kimmel and Short had made “errors in judgment,” they were not guilty of “dereliction of duty.”

Conspiracy theorists continue to have a field day with Pearl Harbor. One idea has President Roosevelt moving the Pacific Fleet from California to Hawaii to lure the Japanese into attacking the United States and thus opening the door to war, which the nation needed to break out of the Depression. However, facts suggest that this was not the case. The fleet was moved at the urging of the State Department because it believed that having the Fleet in Hawaii would deter Japanese aggression—not tempt them to attack.

The congressional committee’s report was not the end of the debate. Many questions remained, but the documents that might answer them would not be declassified for many years.

Why Warnings from Washington Were Not Heeded

As for war warnings from Washington, they were received and acted on, but ineffectively. Kimmel received a dispatch from the Navy Department warning of anticipated aggression by Japan, and Short received a similar warning from the War Department. Kimmel decided not to raise the alert status of the navy forces he commanded because he didn’t want to frighten Pearl Harbor’s civilian population. He did, however, send two aircraft carriers with escorts to deliver planes to Wake Island and Midway, an action that accidentally helped save the valued ships when the Japanese finally attacked.

Short, who was in charge of Pearl Harbor’s defenses, reacted to the warnings from Washington by bolstering precautions against sabotage, considered the main threat because of the island’s large Japanese American population. To that end, he followed military policy and ordered all the warplanes parked wingtip to wingtip so they would be easier to guard. Sadly, the plan only made them a more convenient target for Japanese bombers.

Kimmel and Short were also hobbled in their defense by the fact that they were denied access to intelligence reports based on the decoding of Japan’s communiqués to its diplomats in the United States. Had they known what the intelligence community knew—but failed to share—they might have reacted differently.

The American Response

The Japanese believed that by striking first, they could effectively disable the American military presence in the Pacific and thus prevent any formidable intervention as Japan continued its conquest of smaller nations in the pursuit of land and resources. However, rather than destroying the U.S. military and demoralizing the nation as planned, the attack only strengthened the country’s resolve. Previously, a neutral and politically divided United States might have been content to let Japan continue its warlike ways as long as it didn’t touch American interests or harm American citizens. But with a single blow, Japan managed to unleash the fury of the entire nation.

FDR’s Radio Address

On December 8, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt made the following address, asking Congress to declare war on Japan. Its opening line remains one of the most famous quotes regarding the attack on Pearl Harbor:

Figure 3-3 President Franklin D. Roosevelt addresses the nation following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (ARC 196055)

Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific. Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in Oahu, the Japanese ambassador to the United States and his colleague delivered to the secretary of state a formal reply to a recent American message. While this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or armed attack. It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time, the Japanese government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace. . . .

As commander in chief of the Army and Navy, I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense.

Always will we remember the character of the onslaught against us. No matter how long it may take to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory.

I believe I interpret the will of the Congress and of the people when I assert that we will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will make certain that this form of treachery shall never endanger us again.

Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory, and our interests are in grave danger. With confidence in our armed forces—with the unbounded determination of our people—we will gain the inevitable triumph, so help us God. I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.

A Nation Reeling

On December 8, Congress declared war on Japan by a nearly unanimous vote. Within a day of the declaration of war, long lines formed at every draft board as men clamored to join the service. Most isolationists suddenly changed their beliefs, fully aware that the United States could no longer sit out a war that was threatening to engulf the world. Most people hoped the conflict would be short but knew in their hearts that it would take everything at the nation’s disposal to eliminate fascism’s threat to the world. As men lined up to enlist in the service, women replaced them in the workplace, giving birth to role models like Rosie the Riveter.

The automotive industry became the primary arms maker in the war. An estimated 35 percent of the nation’s ordnance was produced in or around Detroit. General Motors Corporation became the nation’s largest producer of war materials by developing specialties for its divisions. The company’s Cadillac plant, for example, produced tanks and howitzer carriers, while its Chevrolet plant manufactured gears for aircraft engines and axles for army vehicles. The Chrysler Corporation, Packard, and other large manufacturers also did their share of war production, turning out machinery and weapons at an astounding rate. At Ford’s huge River Rouge plant, the largest industrial facility in the world, raw materials arrived by ship, and finished jeeps and trucks moved out from the same docks.

On the afternoon of the attack, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt addressed the nation by radio. “For months now,” she said, “the knowledge that something of this kind might happen has been hanging over our heads. . . . That is all over now, and there is no more uncertainty. We know now what we have to face, and we know we are ready to face it. Whatever is asked of us, I am sure we can accomplish it; we are the free and unconquerable people of the United States of America.”

Hawaii under Martial Law

Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii was deemed a war zone, meaning it was a potential target of invasion and a possible refuge for enemy agents. On the day of the attack, the territorial governor suspended the writ of habeas corpus—the constitutional protection against being imprisoned or detained without judicial approval—and signed a declaration of martial law prepared by the army. General Short, the army commander on Oahu, declared himself military governor. He was relieved of command December 17, but martial law—the most severe since the Civil War—continued until October 24, 1944.

Martial law during wartime was allowed in Hawaii under the same act of Congress that had made the island chain a U.S. territory. As a result of the declaration, the military ordered a strictly enforced nighttime blackout. Anyone caught with a lit cigarette, pipe, or cigar during the blackout was subject to arrest, as was anyone else if the light of their radio dial or kitchen stove burner could be seen through the house windows. The army also instituted a 6:00 P.M. to 6:00 A.M. curfew for anyone not on official business and drew up intelligence reports on 450,000 Hawaiians.

In 1946, the U.S. Supreme Court, after hearing appeals from Hawaiian residents arrested during the war, declared that the writ of habeas corpus should not have been suspended and that declaration of martial law did not automatically allow the military to take over civilian courts, even during wartime.

Fearful of another enemy attack at any time, officials confiscated more than 300,000 acres of land for military use and enacted severe censorship. All outgoing mail was read by military censors, and letters that could not be edited with black ink or scissors were returned to the sender to be rewritten. Long-distance telephone calls were required to be in English so that military personnel could listen in.

Fearing that Japanese invaders might try to disrupt U.S. currency, the military ordered all Hawaiians to turn in all U.S. paper money, which was burned and replaced with bills with HAWAII overprinted on them. In addition, Hawaiians were forbidden to make bank withdrawals of more than $200 in cash per month or to carry more than $200 in cash. To keep track of civilians, the military issued identification cards to everyone over the age of six; anyone caught without a card was subject to arrest.

The military also oversaw the Hawaiian legal system, with military courts trying thousands of cases, most of them having nothing to do with wartime security. People accused of a crime went before a military judge who heard the charges—typically without the presence of a lawyer—and then passed sentence, which could be revoked only by a pardon from the military governor.

Many people fought the sustained martial law. In 1944, a federal judge ruled that military governing of Hawaii was no longer valid, but the military ignored the ruling and President Roosevelt had to step in. In October 1944, he announced the suspension of martial law and the restoration of habeas corpus.

The American Internment Camps

Following America’s entry into the war, thousands of Japanese Americans, German Americans, and Italian Americans were rounded up and placed in internment camps, ostensibly to ensure that they did nothing to help the Axis.

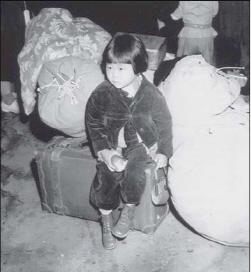

Figure 3-4 Young Japanese girl on her way to an American internment camp.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (210-G-2A-6)

The fear of traitorous acts by Japanese aliens and Japanese Americans was not a new concept. As early as the 1930s, as Japan began to flex its military might in the Pacific, the military expressed concern about such a possibility. The fear was particularly strong in Hawaii, where military intelligence officers created secret lists of potential espionage suspects among the territory’s sizable population of Japanese descent.

Hatred toward Japanese aliens and Americans of Japanese ancestry ignited immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Suspicion ran especially deep in Hawaii, where everyone with Asian features was instantly viewed as the enemy. Newspapers fueled this hysteria with headlines such as “Caps on Japanese Tomato Plants Point to Air Base.” As a result, every Japanese fraternal and business organization was suspected of anti-American activity.

Not all Japanese Americans went willingly to relocation centers. Gordon Hirabayashi fought his internment all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court with the claim that the army had violated his rights as an American. However, the court ruled that the threat of invasion and sabotage gave the military the right to restrict the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans.

Panic Sweeps the Nation

A similar panic quickly swept the mainland, and on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued an executive order identifying specific military areas in the United States that were immediately off limits to Japanese, German, and Italian aliens and Japanese Americans.

On March 18, the War Relocation Authority was established as part of the Office of Emergency Management. Its goal, according to a report to President Roosevelt, was to “take all people of Japanese descent into custody, surround them with troops, prevent them from buying land, and return them to their former homes at the close of the war.”

An estimated 120,000 men, women, and children of Japanese descent were rounded up on the West Coast and taken to ten relocation centers in isolated areas of several states, including Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. Nearly two-thirds of those forced from their homes were American citizens, and more than one-fourth were children under fifteen. The internees were divided into three groups: Nisei (those who had been born in the United States of immigrant Japanese parents and therefore were United States citizens), Issei (Japanese immigrants), and Kibei (Nisei who had been educated primarily in Japan).

Life in an internment camp was hard and demeaning. Internees ate in mess halls, used communal bathrooms, and lived in tarpaper barracks with a twenty-by-twenty-five-foot room allowed for each family. Razors, scissors, and radios were banned. Barbed wire surrounded the camps, and armed soldiers patrolled them. Children went to schools operated by the War Relocation Authority and were routinely indoctrinated with “patriotic” assignments such as writing essays on why they were proud to be Americans.

The camps were, for the most part, quiet and peaceful. The only serious problems occurred at the Tule Lake Relocation Center at the California-Oregon border. In June 1943, Tule Lake was designated a “segregation center” for Japanese Americans who had proclaimed their loyalty to Japan or whom the Department of Justice considered disloyal to the United States. Frequent strikes and demonstrations at the Tule Lake center forced the army to tighten control.

Approximately 2,000 people of German and Italian ancestry were placed in American relocation camps in addition to the 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry.

Japanese American Reactions, Results

Japanese Americans were prevented from entering the service until 1943. When the ban was finally lifted, 9,500 Japanese Americans in Hawaii volunteered for military duty, and 2,700 were accepted. In total, more than 17,000 Japanese Americans fought for the United States in World War II, many of them distinguishing themselves with remarkable bravery. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, whose soldiers were born in America of Japanese ancestry, fought in the Italian campaign and became the most decorated military unit in U.S. history. By the end of the war, members of the unit had received 4,667 medals, awards, and citations, including a Medal of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, and 560 Silver Stars. (See Appendix D for more about medals.)

In 1990—forty-five years after the end of the war—the United States government finally apologized to the 60,000 survivors of internment camps and their heirs. Each received $20,000 in reparations.