Egypt

Great Britain began the first phase of the North African campaign shortly after Italy declared war on June 10, 1940. General Archibald Wavell, commander in chief of British forces in the Middle East, felt it necessary to prove to Mussolini that the Allies were not about to let any Axis aggression go unchecked. Wavell sent a couple of armored vehicles from British-controlled Egypt to the Italian colony of Cyrenaica in Libya. After smashing through the barbed wire fence erected by the Italians, the British force paraded around two Italian forts, then crossed the border back into Egypt. The action was the beginning of a fight that would go on almost to the end of the war.

Mussolini showed little concern for the British presence in Egypt. His forces in the region greatly outnumbered those of the British, and he believed that the British posed little threat to what he saw as the start of the new Roman Empire.

On August 4, Mussolini ordered his forces to invade British Somaliland, southeast of Egypt. The British, greatly outnumbered, quickly withdrew from the territory, and on August 17 the Italian forces took the colony’s capital, Berbera. The move had dire potential consequences for the British; if the United States, still neutral at the time, were to declare the Red Sea unsafe because of the Italian presence, it could cut off an important British supply line.

While Great Britain bolstered its forces and tried to formulate a military response to the Italian invasion of Somaliland, Mussolini, having learned from Hitler that an invasion of England was imminent, encouraged Marshal d’Armata Rodolfo Graziani, commander in chief of Italian forces in North Africa, to press Italy’s advantage by invading Egypt. When Germany was forced to cancel Operation Sea Lion—the invasion of England—Graziani was reluctant to move, but he finally did so at Mussolini’s urging on September 13. Five divisions crossed the border and, despite British resistance, successfully advanced about sixty-five miles to the coastal town of Sidi Marrani, where a strong defensive perimeter had been established.

Wavell was not about to let the Italians take Egypt, and on December 9, a British Western Desert Force of 30,000 attacked the Italian stronghold, taking the Italians by surprise and capturing 20,000 prisoners. Flushed with an easy victory, Lieutenant General Richard O’Connor, commander of the British force, decided to press on into Libya. He very quickly took the border town of Bardia, then proceeded forward, capturing nearly every town his force encountered. In just ten weeks, O’Connor’s army, which was greatly outnumbered in the region, crossed 500 miles, captured the province of Cyrenaica, and took an amazing 130,000 prisoners.

O’Connor felt unstoppable and was eager to advance on the Libyan capital of Tripoli, but Wavell said no. His orders were to supply fresh troops to Greece, so he cut the Libyan force in the hope that the smaller army would still be able to control Cyrenaica.

Germany Enters the African War

The decision not to take Tripoli had serious consequences for the British. On February 12, 1941, General Erwin Rommel, newly appointed commander of Germany’s Afrika Korps, arrived in Tripoli to help Italy get back what the British had taken. Though officially under an Italian general, Rommel, a savvy military strategist and gamesman, pretty much ran the show on his own. In March, after amassing a strong German-Italian force fortified with tanks and heavy artillery, Rommel headed to Cyrenaica. The small British force there was quickly overwhelmed by the German war machine, and by April Rommel had succeeded in retaking everything except Tobruk, where the British had set up a strong defense. Over the course of the campaign, Rommel managed to capture General O’Connor and two other generals who were sent to Italy as prisoners of war, but O’Connor escaped in December 1943.

By the end of his offensive, Rommel had crossed the border into Egypt, where he took Halfaya Pass. Having initially bypassed Tobruk, he returned to lay siege to the fortified port city. Wavell tried to break the German hold on Tobruk with two assaults, code-named Brevity and Battleax, but succeeded only in losing nearly half his armor to Rommel. The defeat was a serious problem for Winston Churchill, who had gone against his military advisers by taking tanks and fighter aircraft from Great Britain and giving them to Wavell. Churchill had no recourse but to replace Wavell with General Claude Auchinleck, who in November 1941 mounted another offensive against the Germans. His goal was twofold: Cover a breakout from Tobruk and recover the territory taken by Rommel.

The battle lasted until mid-December, when Auchinleck’s army successfully lifted the siege of Tobruk and pushed Rommel all the way back to El Agheila. Both sides experienced heavy casualties, but the victory went to Auchinleck, who lost less of his military strength than did Rommel.

However, the German defeat did not mean the end of the war in North Africa. If anything, it only served to accelerate the action. Rommel’s supply lines were far shorter than Auchinleck’s, and his army was soon reinforced, resupplied, and rearmed. The situation might have been quite different had the RAF not been preoccupied supporting British forces in Malta.

On January 21, 1942, Rommel struck again against the British, this time with overwhelming force. He recaptured Benghazi (and the British arsenal stored there) and pressed to within 35 miles of the British stronghold at Tobruk. Startled by Rommel’s strength, the British withdrew to the Gazala line, a series of defensive structures linked by minefields that ran from El Gazala on the coast to Bir Hacheim, approximately 40 miles southwest of Tobruk.

Rommel and Auchinleck paused to regroup and amass supplies. Auchinleck also used the time to reinforce the center of the Gazala line. On May 26, Rommel finally made his move, maneuvering swiftly around the southern end of the Gazala line in the hope of taking Bir Hacheim and then eliminating the defensive boxes one at a time. But things suddenly turned sour for Rommel, who found himself trapped between British bunkers and facing almost certain annihilation.

It was then that Rommel demonstrated his true skill as a military leader. Through sheer drive, he rallied his army to overrun Bir Hacheim, smash a series of British defensive boxes, then make a mad run for a large British supply dump east of Tobruk. Four days later, Rommel’s Afrika Korps swarmed Tobruk, capturing the town and its huge cache of supplies—enough to supply 30,000 men for three months. The only thing denied Rommel was the British gasoline supply, which was set ablaze before the Germans could get to it.

Having lost Tobruk, the British regrouped and formed another defensive line at Mersa Matruh deep inside Egypt. Behind that was a last-ditch defense at El Alamein, which protected Alexandria. If that fell, so would Egypt.

Rommel, his reputation taking on almost legendary proportions, took Mersa Matruh at the end of June, then set his eyes on the El Alamein line, which stretched for 35 miles and was protected at the flanks by a series of natural obstacles that made access extremely difficult. The sea lay to the north of the line, and to the south was the Qattara Depression, nearly 7,000 square miles of terrain so harsh that it was virtually unpassable.

Hitler was extremely pleased with Rommel’s performance and rewarded him with a promotion to field marshal. Unimpressed, Rommel reportedly responded by saying, “It would be better if [Hitler] sent me another division.”

Adding to Rommel’s woes were dwindling supplies, constant harassment by the RAF, and the fact that his men were exhausted after weeks in the desert. As a result, when Rommel’s forces finally reached the El Alamein line on July 1, they lacked the strength and resources to smash through.

Great Britain Reorganizes

Churchill, reacting to the fall of Tobruk, flew to Egypt to review the situation, then replaced Auchinleck with General William Gott. But Gott was killed while flying to take command, so Churchill transferred General Bernard Montgomery and sent him to command the British forces in Egypt. Montgomery, a by-the-book military man, immediately set about strengthening the Eighth Army. He replaced officers he considered lacking in leadership, increased troop training, and arranged for closer air support.

Montgomery correctly assumed that Rommel would attempt to break through at the south end of the line in August, and made sure his Eighth Army was prepared. Rommel attacked on August 31 at exactly the spot Montgomery had anticipated and was quickly repelled by blistering fire. Unable to proceed, Rommel was forced to withdraw.

While Rommel was trying to break the El Alamein line, RAF bombers were doing all they could to destroy the German tanker convoy that was bringing the Desert Fox the fuel he needed to continue. Meanwhile, Montgomery enjoyed a plentiful resupply effort from the United States. At Churchill’s request, President Roosevelt had authorized the loan of Sherman tanks and artillery to assist Montgomery’s defense.

Two months after Rommel’s ineffective drive against the El Alamein line, Montgomery began a remarkably strong offensive campaign designed to force the German-Italian forces into a retreat. The Eighth Army quickly decimated four German divisions and eight Italian divisions and captured nearly 30,000 prisoners. Montgomery then turned his attention to the fleeing Rommel. On November 20, 1942, Benghazi fell, and three days later Rommel was back where he started, in El Agheila. The Eighth Army chased Rommel through Libya, taking Tripoli on January 13, 1943, and eventually made its way to French North Africa, where it hooked up with other Allied troops in April.

The Northwest Africa Campaign

Northwest Africa was a strategic goal for both the Allies and the Axis since the fall of France in 1940. Germany’s conquest left the French-held territories in North Africa open to occupation, while the British were eager to keep Germany away from French North Africa and its military installations. The British were fearful that Germany and Italy, already in Northeast Africa, would bring reinforcements through Italy.

The campaign offered both political and military benefits. On the home front, Roosevelt believed that military action in Northwest Africa would stimulate morale among Americans while putting U.S. forces into action. It was also a way to placate Stalin, who had been calling for a second front against Germany. At the same time, an invasion of the region would provide a staging ground for action against Italy while putting pressure on Rommel, who was wreaking havoc in the east.

Roosevelt and Churchill first discussed a joint military campaign in French North Africa at the Atlantic Conference in August 1941, when both men acknowledged that U.S. involvement in the war was just a matter of time. During other meetings in December 1941 and January 1942, the two leaders discussed the idea in greater detail, confident that action in Northwest Africa would help put additional pressure on Hitler.

The campaign was slow to start, however, because of international political problems. For example, the United States had established diplomatic ties with the Vichy government in France, but the British refused because they viewed it as a German puppet government. Relations between Great Britain and Free France, led by Charles de Gaulle, had also taken a bruising. The Royal Navy had attacked French warships to keep them from coming under German control—an act that also enraged the Vichy French. As a result, Great Britain could not contemplate acting alone in French North Africa; diplomacy dictated that others also take part.

Figure 5-1 From a Coast Guard-manned sea-horse landing craft, American troops leap forward to storm a North African beach during final amphibious maneuvers.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (James D. Rose, Jr., ca 1944, 26-G-2326)

The situation changed dramatically in June 1942 when Rommel’s Afrika Korps made substantial gains in Libya and left the Eighth Army in temporary disarray. Churchill met with Roosevelt on June 17 to discuss the issue and agreed on a plan to land in North Africa. The plan was code-named Torch.

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff were uncomfortable with the plan, preferring a larger, more forceful landing in Europe. But they were overruled by Roosevelt, who felt that Operation Torch was a necessary endeavor. Plans for the operation were made during the summer of 1942, as the Soviets continued their push for a second front. Churchill finally told Stalin about Operation Torch in August after Stalin insinuated that the Soviet Union was doing all the fighting against Hitler while the British stood idly by.

The North African Assault

The North African assault—the first joint endeavor between Great Britain and the United States—was put under the overall military command of Lieutenant General Dwight Eisenhower, who was a relative unknown at the time. Royal Navy Admiral Andrew Browne Cunningham was placed in command of all naval forces, and RAF Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder was put in charge of all air operations.

On October 21, 1942, Major General Mark Clark, one of Eisenhower’s deputies, sailed from Gibraltar for a top secret meeting with Robert Murphy, the U.S. consul general in French North Africa, and Vichy representatives in North Africa. Clark’s goal: a promise of assistance from the French or, lacking that, at least a promise that they would not interfere with an Allied landing in North Africa. After two days of talks, Clark received a promise of cooperation. In return, the French were promised a month’s notice of the pending invasion—though, in fact, U.S. warships were already on their way and were expected to reach North Africa in about two weeks.

The goal of the invasion, which began November 8, was to push German and Italian forces out of North Africa by linking the invasion force with Montgomery’s Eighth Army, which in October had broken through Rommel’s lines at El Alamein and forced Rommel to retreat westward across Libya. Unfortunately, the Allies’ plan hit a snag when their push eastward was slowed to a crawl by a lack of air support and rains that turned the roads into unpassable bogs. The Germans reacted immediately by pouring supplies and troops into Tunisia from Sicily by sea and air, capturing airfields in Tunis and Bizerte.

The airfield at Bone had been taken by British airborne troops by November 12, but Allied forces—many of them inexperienced recruits—moved too slowly to take advantage of the Axis rout in Egypt. The situation greatly angered Eisenhower, who fumed at the missed opportunities.

Allied troops on their way to Tunis, hampered by poor weather and dwindling supplies, were stopped by a smaller German force. By the beginning of the new year, the Axis had created a strong defense in Tunis with combined German-Italian forces numbering more than 100,000.

Churchill and Roosevelt were concluding their Casablanca summit in mid-January just as Montgomery and his Eighth Army was pushing westward after Rommel. Montgomery took Tripoli on January 23 and was eager and ready to drive the Axis out of North Africa.

Rommel Combines His Forces

However, the situation proved more difficult than originally thought. Rommel managed to connect his fabled Afrika Korps with a German Panzer division on the Tunisian front and then launched an offensive against Allied forces to the east. Rommel hoped his new combined army would be able to break through the Allied line and enable him to establish a new supply route at Bone.

The German force was formidable, and the antitank guns were almost invincible. American troops took heavy casualties, including the loss of forty tanks in a single battle. On February 14, the Germans broke out of the Faid area with a double thrust maneuver that effectively split the Allied lines and pushed American troops back to the Kasserine Pass, a two-mile gap in the Dorsal mountains of western Tunisia. It was there that American troops met Rommel’s army on February 19. The fighting was heavy, but the U.S. forces were able to hold off the Germans. Rommel received armored reinforcements that night, and the following day—with Rommel in the lead— the Germans attacked again. The Americans fought valiantly, but they were overwhelmed and forced to withdraw. More than 1,000 U.S. soldiers died in the battle, and hundreds were taken prisoner.

From the Kasserine Pass, Rommel advanced toward Tala, 20 miles north, and Tébessa, near Algeria. It was there that Rommel would meet his match. American forces pushed the Germans back at Tébessa, then were joined by Allied forces that sent the Germans into retreat while attacking them from the air. Rommel’s troops retreated through the pass and almost certainly could have been taken, but Allied ground forces missed the opportunity by hesitating to pursue them.

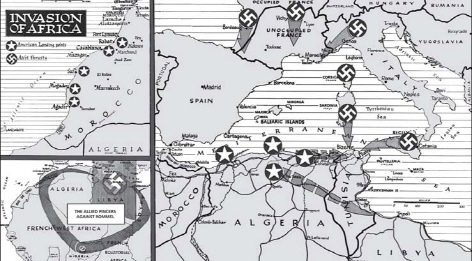

Map 5-1 The invasion of North Africa (Operation Torch) led by Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Map courtesy of the National Archives (RG 160, Vol. 1, No. 30)

Allied Forces Work Together

The combined Axis forces faced the Eighth Army at the Mareth line, a 22-mile length of fortifications built by the French that ran from the sea to the Matmata Hills. While both sides prepared, General Harold Alexander, commander in chief of the British Middle East Forces, was named deputy commander for ground forces in an important command reorganization. Under Alexander were the British Eighth Army, U.S. Army troops, and forces of the Free French—a combined total of more than half a million men.

For nearly a month, from February 26 to March 20, the Axis forces were gradually weakened through a series of battles that took a heavy toll on their troops and equipment. Once the Axis forces had been sufficiently softened up, the Allies prepared for the coup de grâce: a push through the Mareth line. On April 8, patrols from the U.S. forces in the east and the British Eighth Army from the west shook hands near Gafsa, signaling the official linkup that was to drive the Axis from North Africa for good. Rommel, who had become ill, had already been flown to Germany, where he would play an important role in designing the German defense of Normandy. But the Desert Fox would never set foot in Africa again.

The Axis forces were in no position to put up much of a fight once the Allies hooked up and started their push. Desperately low on food and supplies and exhausted from the long retreat from El Alamein, they established one last defensive position encompassing Tunis, Bizerte, and the Cape Bon Peninsula but were quickly overwhelmed. Tunis was captured by the British, Bizerte by the U.S. and French. The German and Italian forces laid down their weapons for good on May 13, and their generals arranged for mass surrenders that eventually totaled more than 240,000 soldiers. North Africa was finally under complete Allied control.

This fact would prove strategically important, as Allied forces gradually took control of the entire Mediterranean region.