The Battle of the Coral Sea

While it was a naval battle in the sense that the opposing forces were on ships, the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 was unique in that the ships did not fire on each other, relying instead on carrier aircraft. The Battle of the Coral Sea was important, too, in that it was the first Japanese setback of World War II.

The Coral Sea is located between Queensland, Australia, on the southwest, the New Hebrides and New Caledonia on the east, and Papua and the Solomon Islands on the north. The battle there resulted from the Japanese plan to take Port Moresby and then threaten the Australian mainland. Capture of Port Moresby would also end Allied attacks against Japanese bases at Rabaul and in the Solomon Islands.

On April 18, 1942—just four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor— American bombers, later known as “Doolittle’s Raiders,” passed over Japan. An Allied attack on the Japanese mainland was thought to be impossible, yet it happened. That first bombing assault actually did little physical damage, but it succeeded greatly in raising American morale and puncturing, at least a little, the veneer of Japanese invincibility.

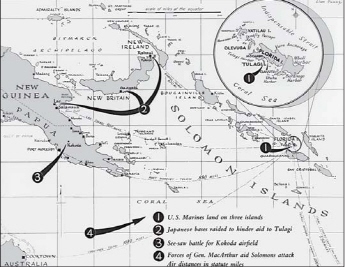

Map 6-1 The U.S. offensive in the Solomon Islands.

Map courtesy of the National Archives (Solomon Islands, RG 160, Vol. 1, No. 17)

For the invasion of New Guinea, the Japanese amassed seventy ships, including two large aircraft carriers, two smaller carriers, and a number of cruisers, destroyers, and supply ships. Thanks to luck in breaking the Japanese code, the U.S. Navy was well aware of the deployment, and plans were made to counter the invasion with a naval task force under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher that included the carriers Lexington and Yorktown and a handful of destroyers and cruisers. It was a force smaller than that of the Japanese, but it was all that was available at the time.

Cat and Mouse

On May 3, 1942, Japanese troops landed on Tulagi in the Solomons, off Guadalcanal. Planes from the Yorktown scouted the area in search of the Japanese fleet but found only a few isolated ships, including three minesweepers and a destroyer, all of which were quickly sunk.

Figure 6-1 A Japanese torpedo bomber explodes after being hit by antiaircraft fire.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-415001)

For the invasion of New Guinea, the Japanese amassed seventy ships, including two large aircraft carriers, two smaller carriers, and a number of cruisers, destroyers, and supply ships. Thanks to luck in breaking the Japanese code, the U.S. Navy was well aware of the deployment, and plans were made to counter the invasion with a naval task force under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher that included the carriers Lexington and Yorktown and a handful of destroyers and cruisers. It was a force smaller than that of the Japanese, but it was all that was available at the time.

At the same time, the Japanese force was searching for the American task force. Japanese planes came across an oiler and a destroyer, sinking both. On May 7, the U.S. force received a garbled message noting the presence of two Japanese carriers and four heavy cruisers. But the message was incorrect—the convoy actually contained two heavy cruisers and two destroyers. A total of ninety-three American aircraft went hunting for the misidentified Japanese carriers, while Japanese reconnaissance planes continued their search for the U.S. fleet.

American planes eventually came across the Japanese light carrier Shoho and its destroyer escorts. The carrier was hit with seven torpedoes and numerous bombs and sank within minutes.

The logistics of the first Tokyo bombing raid were astounding. The flight deck of an aircraft carrier was only 450 feet compared with the standard 1,200 feet or more generally used. Air force pilots practiced extensively on ground mockups of a carrier deck until they had every nuance down pat.

Meanwhile, poor weather prevented the Japanese planes from finding the U.S. carriers, so they dumped their bombs and torpedoes in the ocean and headed back toward their fleet. U.S. fighters on reconnaissance saw the Japanese planes and attacked, shooting down ten while losing two of their own. The air battle raged past sunset, and some of the surviving Japanese planes accidentally stumbled across the Yorktown, which, in the dark, they mistook for their own carrier. Several Japanese planes prepared to land on the Yorktown when the pilot of the lead plane suddenly realized his mistake and immediately throttled up in a desperate attempt to escape blistering antiaircraft fire. Shortly afterward, the surviving planes found their own carriers, which used searchlights to guide the pilots in.

Massive Aerial Recon on Both Sides

More than eighty U.S. bombers and torpedo planes went in search of the Japanese carriers the next day, while the Japanese fleet sent sixty-nine planes after the Lexington and the Yorktown. Astoundingly, the two aerial armadas didn’t see each other as they headed for their respective targets. Torpedo planes attacked the Lexington, sending two torpedoes into its port side. Five bombs also struck the ship, but they did little damage. The Yorktown was also hit by a bomb, which plunged through the flight deck before exploding.

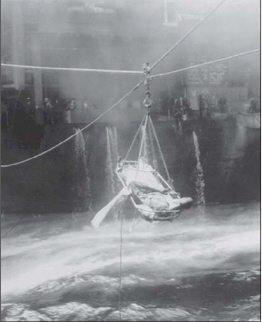

Figure 6-2 Troops and supplies heading into the invasion of Cape Gloucester, New Britain, December 24, 1943.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (26-G-3056)

Numerous internal explosions rocked the Lexington as a result of the Japanese attack, which took 216 lives, and five hours later orders were given to abandon ship. After the crew of more than 2,700 was evacuated, the carrier was torpedoed by a U.S. destroyer to hasten its death.

As Japanese planes attacked the American carriers, bombers and torpedo planes from the Yorktown launched a massive attack against two Japanese carriers. But several torpedoes launched against the carrier Shokaku missed or failed to detonate. In addition, only two bombs found their target. Planes from the Lexington followed with a second attack but also inflicted minimal damage.

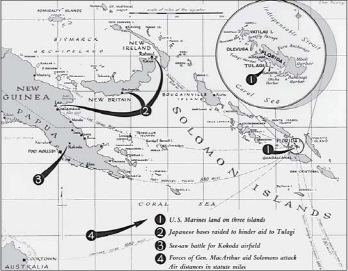

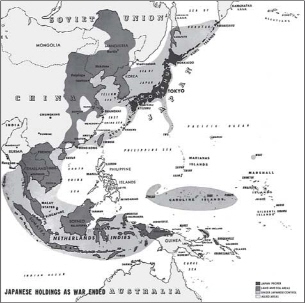

Map 6-2 The height of the Japanese power in the Pacific, China, and Southeast Asia.

Map courtesy of the National Archives (Japanese Empire August 1942, RG 160, Vol. 4, No. 19F)

Map 6-3 The range of Japanese power as the war ended.

Map courtesy of the National Archives (Japanese Holdings as War Ended, RG 160, Vol. 4, No. 19F)

It appeared that the Japanese were the victors in the Battle of the Coral Sea, but the Allies were the tactical winners because the assault damaged a sufficient number of Japanese ships and planes to delay the Japanese expedition against Port Moresby and thus prevented planned air attacks against Australia.

When the order was given to abandon the Lexington during the Battle of the Coral Sea, 2,735 men went over the side and were rescued without a single loss. Accompanying the crew was the captain’s cocker spaniel, Wags.

Wake Island

Wake Island, a small coral atoll approximately 2,000 miles west of Hawaii, is notable as the site of the first lengthy battle between U.S. and Japanese forces.

The United States took possession of Wake Island in 1898, though the island meant little until 1935, when it became an important refueling stop for Pan American Airways Clippers flying between San Francisco and Manila in the Philippines. The U.S. military also took notice of Wake Island, and in 1938, funds were allocated to build air and submarine support bases there. Construction was delayed until 1941, when a civilian crew of 1,200 workers arrived, along with a small navy and marine contingent and an army communications unit. The base was completed by November, and a 388-man marine defense detachment was based there, supported by a variety of heavy guns, many of them scavenged from old World War I battleships.

The Japanese attacked Wake Island the same day they attacked Pearl Harbor. Japanese bombers out of Kwajalein destroyed seven F4F Wildcat fighters on the ground and heavily damaged the base. A Pan American Clipper loaded with tires for the P-40 Warhawks of the fabled Flying Tigers in China was caught on Wake at the time of the attack. Once the Japanese bombers left, the tires were unloaded and burned to keep them out of Japanese hands, and the plane took off.

The American defenders of Wake Island managed to get in a few good hits of their own on December 11 when they damaged three Japanese cruisers, two destroyers, and other ships that were part of an invasion force. The Japanese responded by bombing and shelling Wake Island for twelve consecutive days, then landing an invasion force on December 23. Unable to mount a defense, Navy Commander Winfield Cunningham surrendered.

The Japanese eventually placed 4,400 troops on Wake Island, but the island proved to be of little use. It was bombed repeatedly by U.S. planes, and ships commonly used it as an artillery range. Supplies were slow in reaching the men stationed there, and many suffered from malnutrition. Fewer than 1,200 were left alive when Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara, commander of the Japanese force on Wake, surrendered on September 4, 1945. Sakaibara was tried for war crimes and was executed on June 18, 1947.

Midway

Midway, a U.S. Navy base on two tiny islands that form a coral atoll in the central Pacific, was the site of unsuccessful Japanese attacks in December 1941 and January 1942. The Japanese attacked for the third time in June 1942, and the resulting battle was one of the largest of the war in the Pacific.

The Doolittle raid reached Tokyo just minutes after a practice air raid drill. As a result, most residents of the city thought the planes were part of the exercise. Later, when asked where the bombers had come from, President Roosevelt slyly replied, “Shangri-La.” The U.S. Navy later named an aircraft carrier under construction at the time the Shangri-La.

The Japanese wanted Midway for several reasons. It would be an essential part of Japan’s defensive line in the Pacific. It was also a necessary cog in Japan’s strategy to invade the Hawaiian Islands.

The Battle Ensues

The U.S. naval presence in the Pacific was a constant threat to Japanese imperialism, and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, believed that the U.S. Pacific Fleet had to be completely destroyed in 1942 or Japan would lose the war. A savvy strategist, Yamamoto rightly believed that an attack on Midway would pressure Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, into using everything at his disposal to protect the island, which was integral to the defense of Pearl Harbor.

The attack on Midway was to begin on June 5 with carrier aircraft destroying the island’s ground defenses and aircraft. The next day, according to the plan, Japanese troops would take Kure Island, nearly 60 miles northwest of Midway, and create a base for seaplanes to support the Midway invasion. In addition, a fleet of Japanese submarines was dispersed to intercept U.S. ships sent to Midway and the Aleutians from Pearl Harbor.

Thanks to their code breakers, U.S. Navy officials were well aware of Yamamoto’s plans. Admiral Nimitz decided to send his only three aircraft carriers—the Enterprise, the Hornet, and the recently repaired Yorktown—against the Japanese invaders.

The Japanese invasion force was identified on June 3, but air strikes by bombers out of Midway inflicted little damage. The next morning, bombers and fighters from Japanese carriers attacked Midway.

Aircraft armed with torpedoes were being held at the ready on the Japanese carriers to deal with any U.S. warships that might be seen by Japanese reconnaissance planes. Then a change of orders sent the crews scrambling to swap the torpedoes for bombs so Midway could be attacked a second time.

While crewmen struggled to make the switch, a Japanese search plane saw U.S. warships just 200 miles away. But Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher, commander of the U.S. carrier strike force, was already aware that two Japanese carriers were within easy striking distance. The battle of Midway was set in motion.

Surprise Assault

Acting quickly to maintain the element of surprise, Fletcher ordered Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance to attack the Japanese carriers with planes from the Enterprise and the Hornet. Fletcher planned to follow the two carriers aboard the Yorktown once his scout bombers returned.

Speeding toward the Japanese carriers at twenty-five knots, Spruance decided to launch his planes before the Japanese could launch another attack on the battered station at Midway. This required launching his planes 200 miles out—well short of the torpedo bombers’ combat radius. Nonetheless, fourteen TBD Devastator torpedo bombers were launched from the Enterprise, along with thirty-three dive-bombers and an escort of ten Wildcat fighters. The Hornet launched thirty-five dive-bombers, fifteen torpedo bombers, and ten fighter escorts. Approximately an hour and a half later, the Yorktown delivered seventeen dive-bombers, twelve torpedo bombers, and six fighters.

The Hornet’s fifteen-plane Torpedo Squadron Eight lost contact with the other attack planes but came across four Japanese carriers. Though greatly outnumbered by Japanese Zeros and facing a blanket of antiaircraft fire from cruisers and destroyers, the planes engaged the ships in short-range battle. Plane after plane was shot down by the Japanese Zeros and the barrage of artillery, but the American pilots continued their futile attack. In the end, not a single plane escaped, and none of their torpedoes hit the intended targets. Only one man from Torpedo Eight survived the battle; he was rescued at sea the following day.

Torpedo Squadron Six from the Enterprise attacked next, but it, too, suffered greatly. Of the fourteen torpedo bombers to engage the Japanese, only four survived. And once again, none of the torpedoes hit their targets. Torpedo Squadron Three from the Yorktown suffered a similar fate: all twelve planes lost, with no damage to the Japanese.

But the loss of the torpedo squadrons opened the door for the destruction of the Japanese carriers. Because the planes came in low over the water, the guns on the Japanese ships and all Japanese fighters were drawn down low. As the attack continued, American dive-bombers from the Enterprise arrived on the scene unopposed.

While wave after wave of U.S. torpedo bombers attacked the Japanese carriers, the ships’ crews were working to prepare planes for a counterattack, stacking bombs on the hangar decks of the Akagi and the Kaga. The first few Zeros were taxiing down the Akagi’s flight deck when an American bomb struck the carrier, causing more than sixty newly fueled and armed planes to explode. Four bombs also struck the Kaga, causing the bombs set on its deck to go off.

While the Akagi and the Kaga burned, seventeen dive-bombers from the Yorktown converged on the carrier Soryu, hitting it with three well-placed bombs that ignited the waiting, weapons-heavy planes and sending a fireball of destruction across the ship’s flight deck.

The Battle Winds Down

The fourth Japanese carrier, the Hiryu, was able to launch its bombers against the U.S. carriers, stopping the Yorktown with three bombs. In a second attack, the carrier was hit in the port side by two torpedoes and began taking on water. The order to abandon ship was given, and the ship’s survivors, numbering more than 2,200, crossed into the waiting destroyers and cruisers. The Yorktown’s dive-bombers, which were on the Enterprise, then hooked up with that ship’s bombers to destroy the Hiryu. The job was done with four bombs, which ignited huge fires aboard the Japanese carrier, stopping it dead in the water.

The Battle of Midway is widely regarded as the turning point for the Americans in the Pacific, showing that the Japanese had greatly underestimated them.

Even with the loss of the Yorktown, the Battle of Midway was a decisive blow against the Japanese navy. In addition to the four aircraft carriers, a Japanese cruiser was sunk, and another cruiser and two destroyers were badly damaged. All of the carriers’ 240 planes were lost, along with most of their pilots and support crews.

But all was not lost for the Japanese in the Pacific. The northern phase of the battle succeeded, with the Japanese continuing to the Aleutians because Admiral Nimitz had nothing left to stop them. Japanese carrier aircraft were able to inflict substantial damage on the American base at Dutch Harbor, and the Japanese were virtually unopposed when they landed at Kiska and Attu. They would hold these positions for another year.

The Philippines

This collection of some 7,000 islands, along with Guam and Puerto Rico, was ceded to the United States by Spain after the Spanish-American War. The battles of Bataan and Corregidor fought in the Philippines were two of America’s greatest losses to Japan at the beginning of World War II, but the territory was eventually liberated in 1944.

As a commonwealth, the Philippines relied on the United States for its defense. Retired general Douglas MacArthur, former U.S. Army chief of staff and onetime commander of the army’s Philippine Department, was made the territory’s military adviser.

In July 1941, as the Japanese threat grew more imminent, MacArthur was recalled to active duty and made commander of all U.S. and Philippine troops in the Philippines.

MacArthur believed that the troops under his command were up to the task of keeping the Japanese at bay, and he pretty much ignored the official war plan for defense of the commonwealth, known as War Plan Orange, Revision Three. This plan called for forces to withdraw to the mountainous Bataan peninsula at the mouth of Manila Bay, which was protected at the rear by the fortified island of Corregidor, until reinforcements could arrive.

The plan looked good on paper, but the reality of the situation was quite different. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces immediately turned their attention to the Philippines with an unexpected air attack on U.S. bases that wiped out nearly half of the 200 aircraft stationed there. The following day, December 9, the Japanese made an amphibious landing on Bataan Island off Luzon and seized the airstrip. More Japanese forces arrived the next day, going ashore at two points on northern Luzon. Additional airstrips were quickly seized with almost no opposition because most of MacArthur’s forces were 800 miles away in Mindanao at the southern tip of the Philippine chain.

The Japanese continued gradually increasing their control of the Philippines, finally landing at Mindanao on December 20. They were met by approximately 3,500 U.S. and Philippine troops, but they quickly overwhelmed them. Meanwhile, a major Japanese landing force went ashore at Lingayen Gulf on Luzon’s west coast on December 22, with a secondary landing on the east coast, south of Manila. The Philippine capital became their next goal.

MacArthur hoped to save Manila from destruction by declaring it an open city (meaning it was undefended) on December 26; then he began a withdrawal to the Bataan peninsula, where he hoped to either be rescued or receive reinforcements. Meanwhile, the Japanese disregarded MacArthur’s open-city declaration and began bombing Manila, which fell on January 2, 1942. Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma, the supreme Japanese commander, chose to take Manila as originally planned rather than chase MacArthur and his small army to Bataan. He wouldn’t turn his attention to MacArthur until January 9. This delay gave MacArthur’s troops time to establish a defensive perimeter, though the chances of a rescue were bleak because of the heavy losses the Pacific Fleet had suffered in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

On February 20, Manuel Quezon, president of the Philippines, and several other U.S. and Philippine officials were evacuated by submarine. Once in Washington, Quezon quickly established a government in exile. Meanwhile, President Roosevelt acknowledged the loss of the Philippines and ordered MacArthur to escape to Australia, which he did via PT boat on March 17.

The Battle of Bataan

MacArthur’s forces put up a formidable defense in Bataan, but it wasn’t enough to hold off the much larger Japanese army. On January 9, Homma unleashed a heavy artillery barrage on the defenders, then ordered his men across the Calaguiman River to within 150 yards of the defensive line. Then, he ordered a suicide run by his troops, which pushed the American and Philippine soldiers farther down the peninsula.

But MacArthur’s troops didn’t roll over. Instead, they fought with tremendous ferocity, throwing everything they had at the attacking Japanese. Though continually pushed back, the defenders were able to prevent the swift Japanese victory that Homma had anticipated.

Ordered to evacuate the Philippines by President Roosevelt, MacArthur placed Jonathan Wainwright, newly promoted to lieutenant general, in command of the Philippine army. Boarding the PT boat that would take him to Australia, MacArthur uttered his now-famous farewell: “I shall return.”

Members of the Provisional Naval Battalion, who fought the Japanese during the battle of Bataan, tried to turn their white uniforms khaki for better camouflage using coffee. However, rather than turning brown, the uniforms came out yellow. As a result, one Japanese officer wrote in his diary of seeing “a new type of suicide squad dressed in brightly colored uniforms.”

By this time, the defending army consisted of approximately 500 American sailors and their officers, who formed the Provisional Naval Battalion. Knowing that their task was ultimately futile, the men nonetheless vowed to do everything in their power to hold off the Japanese as long as physically possible.

Homma’s forces received reinforcements in early April, and on April 3, he launched a brutal assault against the weakened American and Filipino defenders. Wave after wave of Japanese soldiers threw themselves at the defensive line with little regard for casualties. Yet despite overwhelming odds, the American and Filipino troops continued to defend themselves with everything at hand, fighting past the point of exhaustion. A week later, on April 9, the valiant fighters, exhausted and out of supplies, finally surrendered.

Before the fall of Bataan, a handful of survivors, including Lieutenant General Wainwright, joined the small contingent of servicemen and nurses on the fortified island of Corregidor, which was next in the Japanese campaign for the Philippines. The Japanese won, but the victory was bittersweet for Homma, who had been given fifty days to take the Philippines. Because he went over schedule, Homma was relieved of command on June 9.

For the survivors of the Battle of Bataan, the worst was yet to come. Taken prisoner, they were forced by the Japanese to march sixty grueling miles from Bataan to San Fernando.

The Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March—involving 76,000 American and Filipino soldiers taken prisoner after the capture of Bataan—is one of the most infamous atrocities committed by the Japanese against Allied servicemen.

During the Bataan Death March, an American prisoner—a former Notre Dame football player—had his 1935 class ring taken from him by a Japanese guard. It was later returned to him by an apologetic Japanese officer who politely explained, “I graduated from Southern California in thirty-five.”

The march began on April 10, 1942, when thousands of prisoners were searched and stripped of personal belongings by Japanese guards. Some of the prisoners were summarily executed, supposedly because they possessed Japanese money. The prisoners were then placed in groups of 500 to 1,000 and forced to march without food or water to a camp under construction at San Fernando in Pampanga Province.

Figure 6-3 American POWs in the Bataan Death March, May 1942.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (127-N-114541)

The march was an exercise in brutality. One soldier reported having his canteen confiscated, the water given to a horse, and the canteen discarded in the bushes. Prisoners who fell behind because of exhaustion were bayoneted and left at the side of the road. The stronger prisoners were not allowed to help.

According to the U.S. War Department, nearly 5,200 Americans died during the twelve-day march, and many more died after reaching the camp. Conditions were so harsh that the death rate at San Fernando reached 550 a day.

The Bataan Death March was a well-kept secret. Word of the atrocities didn’t get out until three years later, when three American officers escaped from the prison camp and revealed the truth. After the war, General Masaharu Homma received much of the blame for the death march. He was convicted of war crimes and executed.

Philippine Resistance

The Japanese began the next phase of their conquest—reorienting Filipinos to view the Japanese not as enemies but as friends eager to help them against the colonialists. The teaching of Japanese became mandatory in Philippine schools, and radios were adapted so they could not pick up American broadcasts. All political parties were abolished, and a new party loyal to the Japanese was started to select members of a pro-Japanese puppet government.

The Japanese had hoped to bring the Philippines into the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere after they conquered it. However, vehemently anti-Japanese forces took to the hills and began an aggressive guerrilla campaign against the invaders. The fighting forces were frequently reinforced and given weapons and supplies via submarine drops, and many of the secret military forces were led by U.S. officers under MacArthur’s command. The movement solidified quickly, and by 1944, the guerrillas had a working recruitment program, communications system, political organization, and even their own currency. Nearly 60 percent of Philippine territory (most of it outlying regions) came under guerrilla control over the course of the war.

Figure 6-4 General MacArthur wades ashore during the initial landing at Leyte following the invasion to liberate the Philippines.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (111-SC-407101)

MacArthur was eager to keep the promise he had made to the Filipino people on his evacuation to Australia, and after his forces made major gains in New Guinea, he started lobbying for the liberation of the Philippines. After much debate, President Roosevelt finally agreed.

The invasion began on October 20, 1944. With two assault forces and 500 ships at his disposal, MacArthur landed more than 200,000 troops on Leyte, which was an important steppingstone to Mindanao and Luzon. The U.S. forces wasted little time in their campaign to retake the island chain. On October 21, they captured the harbor and airfield at Tacloban, the provincial capital of Leyte.

MacArthur had wanted to make the liberation of the Philippines an army operation, but it was the navy that helped propel him to victory as a result of the decisive naval battle of Leyte Gulf, which devastated the Japanese fleet and left the Japanese forces in the Philippines with little air support or supply line protection.

During the naval battle of Leyte Gulf, which enabled General Douglas MacArthur to retake the Philippines by severing Japanese forces’ supply lines, Commander David McCampbell of the carrier Essex shot down at least nine Japanese fighters. McCampbell became the navy’s top fighter pilot in the war with thirty-four confirmed kills.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

The three-day battle of Leyte Gulf, one of the greatest sea battles in history, was Japan’s desperate attempt to disrupt the landing of American troops in the Philippines, as well as drive away the U.S. warships that supported them. Almost the entire Japanese fleet took part in the battle, which started badly for the Japanese with the sinking of two of the first cruisers sent to the region; the ships were torpedoed off the north coast of Borneo, claiming 582 sailors.

Both sides took heavy losses in the battle. When the American carrier Princeton was hit and sunk by a single Japanese bomb, the destruction was so massive and immediate that more than 500 sailors drowned. However, U.S. forces gained immediate and uncontested air superiority and quickly changed the course of the battle by sinking the Japanese battleship Musashi.

During the engagement, the Japanese lost thirty-six warships and the United States lost six. The battle signaled the end of Japanese aggression in the Pacific and introduced a last-ditch weapon from the Japanese: the suicide corps known as the kamikaze, or “divine wind.” On October 25, the last day of the battle, one kamikaze pilot plunged his plane into the flight deck of the American escort carrier St. Lo, igniting the bombs and torpedoes stored below. The ship went down less than a half hour later.

Even though the invasion force met little resistance at Tacloban, the landing at Ormoc on December 7 was a different story. Japanese soldiers hiding in caves and carved-out pillboxes threw everything they had at the Americans while kamikaze raids inflicted heavy damage on U.S. support ships just off shore. A week later, nearly 16,000 U.S. troops and 15,000 construction and army air force personnel landed at Mindoro, quickly overwhelming the 500-man Japanese garrison there. Leyte was secured by Christmas, and MacArthur turned his attention to Luzon, which was being protected by nearly 250,000 Japanese troops.

The Landing at Luzon

The initial landing forces at Luzon met very little resistance, a situation that perplexed the U.S. commanders. It was later learned that the Japanese had opted to let the beach landing take place unopposed so the Japanese defenders would not lose men to the aerial bombardment that usually accompanied such an action. The Japanese, entrenched in a maze of tunnels and pillboxes, fought hard, hoping to prevent an invasion of Luzon and the Philippines’ other main islands.

However, on January 31, 1945, U.S. troops pushed into Manila, beginning a battle that lasted more than a month and involved intense house-to-house and hand-to-hand combat with Japanese defenders unwilling to give up. In Manila, U.S. rangers, backed by Filipino guerrillas, freed a large number of American POWs, including many survivors of the Bataan Death March.

On March 3, MacArthur proclaimed Manila a secure city and returned civil control of the territory to the former Philippine government.

American forces liberated the Philippines piece by piece, with fighting that continued throughout the islands for several more months. General Tomoyuki Yamashita led his force of 65,000 into the hills around Luzon and continued to harass American and Filipino forces until the end of the war.

Aftermath of Occupation

Four years of war took a horrible toll on the Philippines. The Japanese destroyed countless homes, buildings, infrastructures, and farmland. Reconstruction had to be postponed because the Philippines were a primary staging area for a planned invasion of the Japanese mainland. (The Japanese surrender after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki eliminated the need for the invasion.)

After the war, the United States gratefully thanked its ally with eight years of free trade, generous quotas on imports, and a $400 million fund for the payment of war-damage claims. The United States also provided a $120 million public works program and turned over $100 million in surplus properties to the Philippine government. The greatest gift of all came on July 4, 1946, when the Philippines was granted its independence.

The Battle of Guadalcanal

The battle of the Solomon island known as Guadalcanal, which started in August 1942, began the first U.S. offensive of the war in the Pacific. It would prove to be a vicious battle, with heavy losses on both sides.

The invasion, code-named Operation Watchtower, began on August 7 with marines going ashore at Florida and Tulagi Islands, located just north of Guadalcanal, and nearby Tanambogo and Gavuru Islands. Japanese opposition on these secondary islands was much stronger than what the marines landing on Guadalcanal itself faced. It was later learned that the Japanese forces on Guadalcanal had been taken by surprise because poor weather kept their surveillance planes on the ground.

Figure 6-5 U.S. Marine Raiders in front of a Japanese dugout on Cape Totkina on Bougainville, Solomon Islands, which they helped to take in January 1944.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-205686)

It would take an entire day for the Japanese forces on Guadalcanal to realize they were being invaded. During that time, more than 11,000 marines stepped ashore, in addition to the 6,800 who landed on the other islands. The Japanese finally reacted with a hasty air attack out of Rabaul, which inflicted little damage on the U.S. forces.

The goal of the Guadalcanal invasion was the nearly finished Japanese airfield there, an important element in Japan’s planned invasion of New Guinea. The Japanese, outgunned and outmanned, quickly withdrew from the unfinished airfield as the marines approached, and the area was secured and renamed Henderson Field, in honor of Major Lofton Henderson, a marine pilot killed in the Battle of Midway.

Japan Fights Back

However, the Japanese were not about to give up Guadalcanal without a fight. Using barges and transports from Cape Esperance, they were able to quickly unload a considerable armed force. Japanese military leaders then turned their attention to U.S. naval forces in the area, engaging them in a number of battles that would play an important role in whether the marines would be able to take and control Guadalcanal.

The first Medal of Honor ever awarded to a marine went to Sergeant John Basilone. During the Battle of Guadalcanal, Basilone killed so many Japanese in one firefight that he had to send out fellow marines to clear his field of fire. The recommendation for Basilone’s medal said he had contributed “materially to the defeat and virtually the annihilation of a Japanese regiment.”

The Japanese won a decisive naval victory off Savo Island, sinking four Allied cruisers while experiencing minimal damage themselves. The victory allowed Japan to pour reinforcements into Guadalcanal, but Japanese military leaders grossly underestimated the number of marines on the island, and the first small detachment sent to the beach was quickly eliminated. The next wave of Japanese reinforcements was considerably larger, numbering nearly 1,500 men in five protected transports. However, the U.S. naval victory in the battle of the eastern Solomons helped destroy most of the invading force, and those who did make it ashore did so without heavy weapons.

It became increasingly difficult to bring supplies to the entrenched marines, and food, water, and other necessities quickly became scarce. Reinforcements arrived before the situation turned critical. The Japanese also received reinforcements from ships, almost always at night, in a relay that came to be known as the Tokyo Express. However, the added forces were never enough to regain control of the island.

Japan’s Final Push Fails

The largest reinforcement effort by the Japanese occurred in mid-November, when an attempt was made to land 10,000 men. However, no matter what the Japanese tried, they couldn’t establish a strong foothold on Guadalcanal, and by December a complete evacuation was considered. The order was approved by Emperor Hirohito (since Japanese forces were loath to retreat lest they lose face before their emperor), but the actual evacuation didn’t take place until February 1943. So secretive had the Japanese been about the withdrawal that the marines didn’t even realize they’d abandoned the island until they found empty boats and abandoned supplies on the beaches of Cape Esperance.

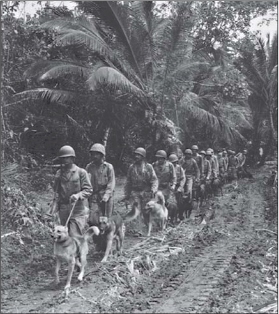

Figure 6-6 U.S. Marines with scouting dogs on the Solomon Islands, circa November 1943.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (127-GR-84-68407)

The Battle of Guadalcanal was a costly defeat for Japan. More than 25,000 Japanese soldiers lost their lives (nearly 9,000 from starvation and disease) both defending and then trying to wrest the island from the marines. U.S. losses totaled 1,500 dead and 4,800 wounded.

The Battle of Iwo Jima

The Battle of Iwo Jima, memorialized for all time by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal’s inspiring photograph of marines raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi, was one of the bloodiest engagements of the entire war. When it was over, almost all of the 21,000 Japanese defenders were dead. U.S. losses totaled 6,821.

Iwo Jima lies only 660 miles from Japan. Because of its relative proximity to the Japanese mainland, it was an essential target for U.S. forces. The Japanese knew this and created a tremendous defense on and beneath the island. More than 600 pillboxes and gun positions dotted Iwo Jima, which also contained a number of caves.

Because the Japanese were so well entrenched on Iwo Jima, U.S. forces spent seventy-four consecutive days softening it up with a constant barrage of shells and bombs from air and sea. The bombardment, which began in November 1944, was the longest of the war, but it was necessary if the island was to be taken.

Underwater demolition teams were used to survey the proposed landing sites and clear away anything that might impede troop carriers. But the Japanese misidentified the demolition teams as an actual landing force and opened fire, killing 170. The mistaken attack gave away hidden gun positions, which greatly aided the invasion planners.

Operation Detachment—the actual amphibious landing of U.S. troops— began on February 19, 1945, observed from a special amphibious command center by Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. The first divisions to hit the beach were greeted with only sporadic gunfire. But once all seven battalions were on the beach, the Japanese let loose with a blistering defense. Antitank guns picked off marine tanks stationed on the beach while the troops pinned down on the volcanic sand were hit with machine gun fire. When the sun set, 566 marines had been killed and 1,854 wounded.

The goals of the invasion were 550-foot Mount Suribachi and an airfield directly inland. By the second day of the assault, the marines targeting Mount Suribachi had advanced just 200 yards, their movements impeded by incessant Japanese gunfire. Members of the Twenty-eighth Regiment of the Fifth Division spent three full days battling their way up the volcano, using flamethrowers and grenades to clear the Japanese ahead of them. On the morning of February 23, the marines reached the top of Mount Suribachi, where they planted an American flag.

Figure 6-7 The planting of the flag at Iwo Jima.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-413988)

A total of twenty-seven Medals of Honor were awarded to the fighting men who risked their lives to take the tiny island of Iwo Jima. It was the largest number awarded for any single action of World War II.

The Battle of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa came late in the war, when Japan was down to its last defenses. Its fleet in the Pacific had been devastated by several strategic losses, and it had lost almost all the territory it had gained at the war’s beginning. With the Allies practically knocking on their door, Japanese military leaders had become desperate. Okinawa had to be held or all was lost.

The 100,000 Japanese troops amassed on Okinawa fully understood the situation. To that end, they had vowed to eliminate as many of the enemy as they could through whatever means necessary. The motto of the Thirty-second Japanese Army confirmed the soldiers’ dedication: “One plane for one warship. One boat for one ship. One man for ten enemies. One man for one tank.”

Because of the passion of the Japanese defenders, Okinawa was a hard-fought and bloody engagement that resulted in huge casualties. When it was finally over in June 1945, more than 107,000 Japanese and Okinawan soldiers and civilians had been killed, and another 4,000 Japanese perished when the battleship Yamato was destroyed on its way to support the Japanese Okinawan defense. American losses on the island totaled 7,613 dead or missing in action and more than 31,000 wounded. An additional 4,907 sailors and marines were killed and 4,824 wounded aboard U.S. ships supporting the island assault.

The U.S. invasion fleet contained almost 1,500 combat and support vessels— the largest number of ships involved in a single operation over the course of the war in the Pacific. The British also contributed a carrier task force of 21 ships, with 244 aircraft on 4 carriers to supplement the nearly 1,000 U.S. carrier aircraft. The number of fighting men involved in the operation totaled nearly half a million, representing the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marines, and the Royal Navy.

Operation Iceberg

Operation Iceberg, as the invasion of Okinawa was code-named, was scheduled to begin on March 1, 1945. But it had to be postponed to April 1—Easter Sunday—because of delays in the Philippines campaign and at Iwo Jima, where the Japanese were forcing the marines to pay heavily for every yard they took.

A preinvasion bombardment of Okinawa started a week before the landings, and on March 26, U.S. forces captured five small islands in the Kerama Retto group west of Okinawa. This would help stop suicide boats based on the islands from being used against the invading forces.

The landing itself began at 4:06 A.M. on April 1 with a feint toward the southwestern shore of the island. This was designed to reduce the Japanese forces at the real landing site, a five-mile stretch on the southwestern coast near two strategic airfields. Marines and army troops went ashore as planned and achieved their immediate goals relatively quickly with a minimum of opposition.

Fatal Defense

The Japanese began their defense with kamikaze attacks against the naval task force supporting the invasion. Nearly 1,900 suicide sorties were flown from April to July, and more than 260 ships were sunk or damaged. According to military records, 2,336 Japanese aircraft were destroyed by U.S. planes and naval guns.

Figure 6-8 Transfer of wounded from the USS Bunker Hill to the USS Wilkes-Barre. The injuries were sustained as a result of a Japanese kamikaze attack off Okinawa, May 11, 1945.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (080-G-328610)

The Japanese sacrificed the island’s airfields so they could fortify their defenses along what came to be known as the Shuri line, named after a nearby castle. American forces first hit the line on April 4; the resulting battle lasted eight days as American soldiers struggled to take a ridge and clear Japanese fighters from the area’s many caves. An offensive against the Shuri line was launched on May 11, but the Japanese were able to repulse the American forces. The First Marine Division finally captured Shuri Castle on May 29.

Renowned combat journalist Ernie Pyle was killed by a Japanese sniper on the island of Ie Shima during the battle to take Okinawa.

Unable to hold the line, the Japanese evacuated Shuri and established another defensive line at Yaeju Dake and Yazu Dake to the south. Vicious fighting continued on Okinawa until the last week of June, with the U.S. campaign officially ending in a successful conquest on July 2.

The Battle of Okinawa is unique because of the high number of cases of “combat fatigue” (now known as posttraumatic stress disorder) that resulted. More than 26,000 American servicemen who fought on Okinawa were later treated for psychological problems due to the ferocity and intensity of the fighting and the almost nonstop artillery and mortar fire that accompanied it.