Adolf Hitler

No other twentieth-century world leader achieved the degree of infamy that Adolf Hitler did. A power-mad dictator intent on world conquest, Hitler used Germany’s tattered national pride and raging anti-Semitism as steppingstones to create one of the most heinous and morally repulsive governments in world history. Millions of people died as a result of Hitler’s lust for power, and his name has justly become synonymous with hate, intolerance, and evil.

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, in Braunau, Austria, the fourth child of Klara and Alois Hitler. His father worked for the Austrian customs service and was able to give his family a comfortable lifestyle.

Hitler’s father died in 1903, leaving the family without a strong male figure. With no one to drive him, Hitler began skipping school, and his grades continued to drop. He left school in 1905 with a ninth-grade education.

When his mother died in 1908, Hitler pretended to continue his education in Vienna in order to receive an orphan’s pension. However, he spent most of his days wandering the city streets and dreaming about his future. Hitler eventually ended up in a homeless shelter, where he was first introduced to the racist concepts that would be the cornerstone of his political ideology. He also developed an intense hatred for socialism, which he came to associate with Jewish people. From 1910 to 1913, he was able to eke out a meager living painting postcards and sketches. Then he moved to Munich, Bavaria, in Germany.

Hitler in the First World War

Hitler volunteered for a Bavarian unit during World War I and fought through the entire war. He returned to Munich after the war and was selected to be a political speaker by the local army headquarters, which trained him as an orator and allowed him to practice public speaking before returning prisoners of war. Hitler excelled as a public speaker and was selected as an observer of political groups around Munich. As part of his job, he investigated the German Workers’ Party, a nationalist group steeped in racism. It was here that Hitler found his soul mates.

Birth of the Nazi Party

Hitler embraced the German Workers’ Party and became an active member. He renamed the organization the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (commonly abbreviated as the Nazi Party) and became its spokesman— despite the fact that he was still technically employed by the army.

Hitler used his deft speaking skills to promote the organization, drawing huge crowds wherever he lectured. When he presented the party’s official program to a gathering in February 1920, more than 2,000 people were in the audience. Discharged from the army in March, Hitler threw all his energies into the new political party, quickly rising to become its leader. He learned early on how to use treachery and backroom scheming to eliminate opposition, a skill that would serve him well in the years to come. On July 29, 1921, Hitler was chosen Führer (absolute leader) of the growing political organization.

The swastika was adopted by Hitler as the emblem and primary flag motif of the Nazi Party during the organization’s infancy. Hitler adopted the design as a symbol “for the victory of the Aryan man.” However, the symbol is actually very old. Similar designs were used by ancient Greeks, Tibetans, and some Native American tribes and are widespread in India.

On November 8, 1923, Hitler attempted his infamous Beer Hall Putsch, a revolution designed to push out the current ruling party and install himself as leader of the German people. The “revolution”—in truth, a small riot— started at a beer hall in Bavaria and quickly spread to the streets, fanned by some 600 of Hitler’s faithful followers. It was quickly put down by armed police, and Hitler was arrested for treason. Though he might have faced life in prison for his acts, he was sentenced to just five years and served only nine months. Though the revolt had failed, Hitler actually came out ahead. The act gained him tremendous publicity and convinced him that the most effective political change came not from an outside force but from maneuvering within. Hitler knew he would have to become part of the government in order to take it over.

Hitler returned to the helm of the Nazi Party after his release from prison in 1924 and spent the next several years creating a network of local party organizations throughout Germany in an attempt to bolster the party’s political strength and influence. He also organized the black-shirted Schutzstaffel, or SS, an elite corps created to protect him, control the party, and perform certain police tasks.

Hitler’s rise to power continued with the 1928 election. Though the Nazi Party garnered just under 3 percent of the vote, it received quite a bit of publicity, and its membership grew. Two years later, new elections increased Nazi representation in the Reichstag, the German parliament, from 12 to 107. Because of the Great Depression and the Nazis’ campaign to cancel all of Germany’s financial obligations, foreign investors fled the country, resulting in the collapse of the German banking system. As the nation’s economic woes worsened, the simplistic appeal of the Nazis grew, and more and more people joined the party. In the 1932 elections, the Nazis received more votes than any other party, and Hitler demanded that President Paul von Hindenburg appoint him chancellor. Hindenburg was initially reluctant but finally agreed. Hitler had now achieved the political clout necessary to make him absolute ruler.

One of the most vivid and frightening film images of wartime Germany is of thousands of hysterical Nazi supporters raising their hands in stiffarmed salute to their Führer while screaming “Heil Hitler!” (Long live Hitler!) It’s an image that, once seen, is difficult to forget. The salute was used by members of the Nazi Party and other civilians to show their allegiance.

Der Führer

After Hindenburg’s death, Hitler became the Führer of Germany, consolidating his power with astounding speed. By that time, the Nazi Party was in complete control of the nation, and Hitler immediately began his despicable racial policies designed to eliminate all undesirables—particularly the Jewish people. Many prominent Jews, fearing for their lives, fled the country.

Hitler also started immediate rearmament and militarization of Germany, despite the fact that it violated the Treaty of Versailles. Though he was chastised, other nations did nothing to stop him. As his arsenal grew, Hitler planned four distinct attacks in his drive to conquer Europe and then the world: Czechoslovakia, Britain and France, the Soviet Union, and finally the United States.

Hitler wasted little time putting his military plan into action. He aligned himself with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. By the middle of 1940, the German despot had taken much of Europe through political scheming and sheer military might. The USSR proved more difficult than originally assumed, however, and the tide of the war changed dramatically with the entry of the United States.

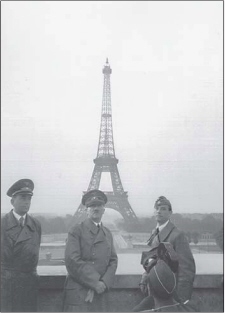

Figure 7-1 Adolf Hitler after the conquest of France, June 23, 1940.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (242-HLB-5073-20)

The German military machine achieved tremendous victories but was hampered by Hitler’s unwillingness to delegate authority where necessary and his “no retreat, no surrender” policies. Victory in war often comes from a strategic pullback and regrouping, but Hitler almost always refused to let his commanders do this, particularly during the Soviet campaign. As a result, a huge number of men and equipment were lost unnecessarily over the course of the war. In the big picture, the German army’s worst enemy was its commander in chief.

The Allies were able to get an important foothold in Europe with the Normandy invasion in June 1944, and the push toward Berlin began in earnest. By this time, the German army was facing overwhelming defeat. A growing number of Germans believed that the only way to end the carnage was to assassinate Hitler, but several attempts failed.

Hitler launched his last desperate offensive of the war in the fabled Battle of the Bulge—in December 1944. The attack managed to push into the Allied defensive line, but the Allies rallied to drive the Germans back.

Hitler’s Final Days

As Allied troops advanced on Berlin, it became apparent that the end was near. Hitler chose to take his own life rather than face trial and judgment in the world court.

Preparing for death, Hitler married his longtime girlfriend, Eva Braun. His marriage to Braun was performed on April 28, 1945, by a Berlin municipal councillor. During the ceremony, both Hitler and Braun swore they were “of complete Aryan descent.” A party followed the ceremony, but few people felt like celebrating.

Hitler then set about dictating his will and political testament. He appointed Karl Dönitz as his successor and encouraged his countrymen to continue their opposition to “international Jewry.” He also noted that his decision to die was made voluntarily, as was his decision to stay in Berlin.

Shortly after 2:00 A.M. on April 30, Hitler bade farewell to his two secretaries and about twenty other people as exploding Soviet artillery echoed above. He then retired to his room with Braun.

Hitler emerged alone the following day for lunch. Shortly after, he ordered his chauffeur, Erich Kempka, to get some gasoline from the Chancellery garage. Hitler and Braun then returned to their private quarters, where Hitler shot himself through the mouth and Braun took cyanide. Kempka and some aides carried their bodies into the Chancellery garden, doused them with gasoline, and set them on fire. Just hours later, Berlin fell to the Allies.

Benito Mussolini

Renowned both for his shaved head and for making the infamously bad Italian train system run on time, dictator Benito Mussolini plunged his nation into a global conflict for which it was woefully unprepared. Aligning himself with Adolf Hitler, he sought world domination—only to lose the support of his own people and ultimately his life.

Benito Mussolini was born on July 29, 1883, in Dovia di Predappio, Italy. His father was a blacksmith and his mother an elementary school teacher. Mostly self-educated, Mussolini became a teacher and socialist journalist in northern Italy. He married Rachele Guidi in 1910 and fathered five children.

Mussolini opposed Italy’s 1912 war with Libya and was jailed for expressing his views. Shortly after his release, he became editor of Avanti!, the Socialist Party’s newspaper in Milan. He initially opposed involvement in World War I, considering it “imperialist,” but changed his mind and called for Italy to fight on the side of the Allies. He was expelled from the Socialist Party and soon started his own newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia (The People of Italy), which would eventually become the voice of the Fascist movement.

Mussolini and several other young war veterans formed the Fasci di Combattimento in March 1919. The organization, which took its name from the fasces, an ancient symbol of Roman discipline, promoted a nationalistic, antiliberal, antisocialist position that attracted many middle-class Italians. The party, its members dressed in telltale black shirts, grew quickly, making a name for itself by attacking peasant leagues, socialist groups, and any others it deemed a threat to Italian nationalism.

Il Duce

In 1922, the Fascists—under direction from Mussolini—marched on Rome. A nervous King Victor Emmanuel III invited Mussolini to form a coalition government. He seized the opportunity, and within four years was able to maneuver the nation into a totalitarian regime, with himself as Il Duce (the leader).

Eager to create a modern Roman Empire, Mussolini defied the League of Nations and, in a very quick war, conquered Ethiopia in 1936. The populace supported this initiative, but Mussolini’s popularity quickly plummeted when he backed Generalissimo Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War, developed an alliance with Nazi Germany, legislated anti-Semitism, and invaded Albania in 1939.

The relationship between Hitler and Mussolini was primarily one of convenience for both men. Hitler saw Mussolini as a role model who could teach him much about dictatorial control. However, as Mussolini made one mistake after another, Hitler lost his respect for the Italian leader. Mussolini, on the other hand, disliked Hitler from the beginning.

Promising to support Austrian independence, Mussolini described Hitler to an Austrian official as “a horrible sexual degenerate, a dangerous fool.” According to Mussolini, fascism recognized the rights of the individual, as well as of religion and the family. Nazism, on the other hand, was “savage barbarism.”

However, as much as Mussolini found Hitler foolish, he couldn’t help but be impressed by Hitler’s quick rise to power and his accelerating military might. In October 1936, Germany and Italy signed a secret alliance that promised a joint effort on issues of foreign policy. The pact was the beginning of the Axis.

In September 1937, Mussolini met Hitler on the Führer’s home turf. He toured German military factories and attended a huge rally in Berlin. The two men joined hands before the massive crowds and pledged eternal cooperation.

The Puppet

Mussolini was eager to join the war in Europe after Hitler’s conquest of Poland but was forced to wait until his own army could be strengthened. Italy officially entered the war in June 1940 after Germany had taken France. In quick succession, Italy attacked British territory in Africa, invaded Greece, and joined Germany in dividing Yugoslavia and attacking the Soviet Union. Italy eventually also declared war on the United States.

But Mussolini’s Italy was not Hitler’s Germany, and some early military successes were quickly countered by major defeats. The country’s unprepared army was devastated by heavy casualties, and the Italian people began to question their role in the global conflict. On July 16, 1943, after the Allied invasion of Sicily, Italian Fascist leaders met with Mussolini and demanded a session of the Fascist Grand Council. Mussolini, sensing that his days as ruler of Italy were numbered, stalled with the excuse that he would soon be meeting with Hitler. Mussolini hoped to peacefully end his nation’s alliance with Germany, but Hitler was able to talk him out of it.

On July 24, the Grand Council met for the first time since 1939. After Mussolini offered a lengthy speech on Italy’s current position in the war, the council voted to depose him. King Victor Emmanuel deposed Mussolini on July 25, 1943, and replaced him with Marshal Pietro Badoglio, chief of the Italian General Staff. In September, King Victor Emmanuel and Badoglio brokered an armistice with the Allies—who had invaded southern Italy— that effectively removed Italy from the Axis.

Mussolini was arrested shortly after his removal from office, possibly because Italian authorities hoped to use him as a bargaining chip with the Allies. Though moved to a number of locations over the next couple of months, he was finally rescued by a German raid on September 12 and flown to Vienna, then to Munich, where he was reunited with his wife. On September 14, Mussolini met with Hitler at the Führer’s compound in Rastenburg.

Hitler placed Mussolini in charge of a puppet state in northern Italy known as the Italian Socialist Republic. But the job came at a hefty price. In exchange for his freedom, Mussolini was forced to give Germany Trieste, the Istrian Peninsula, and South Tyrol.

Mussolini had little real authority over his nonexistent state, which was actually controlled by the Germans. However, in January 1944 he used what little power he had to order a public trial of his son-in-law, Galeazzo Ciano, who had been arrested by the Germans the previous August. Mussolini was enraged that Ciano had participated in his ouster as the leader of Italy and wanted to make examples of Ciano and four other former members of the Fascist Grand Council. Ciano and the others were found guilty of treason and executed by firing squad on January 11.

As the Allies swept through Italy in April 1945, Mussolini visited his wife in Milan and encouraged her to flee the country. He left Milan in a motorcade with his longtime mistress, Clara Petacci. On April 27, Italian partisan guerrillas stopped the motorcade at gunpoint near Dongo on Lake Como and yanked Mussolini and Petacci from their cars. The next day, Mussolini, Petacci, and twelve other captured Fascist leaders were executed by the guerrillas and their bodies hung upside down from a gas station girder in Milan. Allied officials eventually ordered the bodies removed.

The bodies were buried in an unmarked grave. Later, Mussolini’s body was removed and buried in Predappio next to his son Bruno, who had died in a 1941 air crash.

Winston Churchill

Few leaders had as much influence over the course of World War II as British prime minister Winston Churchill. With unflagging strength and vitality, he rallied his beleaguered people when things looked their bleakest, never wavering from his belief that the Allies would eventually emerge victorious. As a result of his tenacity and dedication, most historians consider him the greatest British leader of the twentieth century.

Churchill was born on November 30, 1874, at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire to an old and very aristocratic family. He was the oldest son of Lord Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill, a British statesman who rose to be chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the House of Commons. His mother, Jennie Jerome, was American by birth, the daughter of a New York financier.

In his youth, Churchill developed a deep interest in military affairs and warfare, and his later years at Harrow School prepared him for the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, from which he graduated with honors. In 1895, Churchill was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Fourth Queen’s Own Hussars, a regiment of the British army. On military leave as a war correspondent for a London newspaper, he covered the Spanish army’s attempts to quell a rebellion in Cuba. It was during this endeavor that Churchill came under enemy fire for the first time.

Churchill Enters Politics

Churchill resigned his army commission in 1899 and, in keeping with his family history, turned to politics. He ran for a seat in Parliament as a Conservative candidate but was defeated. Working as a journalist, he went to South Africa to cover the Boer War and was captured by the Boers and imprisoned in Pretoria. He escaped and caught a train to Portuguese East Africa, a feat that made him a hero back home. Churchill later returned to South Africa and sought another army commission. He fought during the Boer War and again wrote about his exploits.

Churchill’s wartime activities made him famous in Great Britain and paved the way for his election to the House of Commons. Though a Conservative, he butted heads with the Conservative leadership over a number of issues and eventually took a seat with the Liberal Party. Churchill’s political star continued to climb for the next several years. In 1908 he married Clementine Ogilvy Hozier, who bore him five children, one of whom died in childhood.

In 1911, as world events were leading to World War I, Churchill was appointed first lord of the admiralty by Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith. Churchill was instructed to create a naval war staff and to maintain the fleet in constant readiness for war. Under his guidance, the British navy became a formidable force, and when war broke out in 1914, its presence in the North Sea helped keep the German fleet under control. Churchill was an active participant during World War I, aiding the Belgians at Antwerp (though the port was lost) and working to develop armored tanks that he believed would help end the stalemate in Europe. His work greatly helped the Allied effort, though Churchill would later become the scapegoat for the failed land campaign at the Gallipoli Peninsula on the Dardanelles. (The campaign actually failed because of delays and incompetent leadership.)

After World War I, Churchill was appointed to the War Office and then to the Colonial Office. In the next election, he was defeated as the Conservatives returned to power, and he found himself cast from the House of Commons for the first time since 1900. Churchill turned again to writing, penning a comprehensive history of World War I, among other books. He won election in 1924, once again as a Conservative, and remained in the House of Commons for the next four decades.

Churchill’s career and popularity ebbed and flowed over the next several years. He supported King Edward VIII in the controversy over his romance with Wallis Warfield Simpson, which eventually led to Edward’s abdication from the throne, and this cost Churchill heavily in the opinion polls. It also widened the rift between Churchill and Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. In addition, Churchill continued to sound frequent warnings about Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, though few people listened.

World War II Breaks Out

When World War II broke out, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain asked Churchill to become a member of his war cabinet. He was again made first lord of the admiralty and immediately began efforts to bolster the Royal Navy, particularly in the area of antisubmarine warfare.

Public confidence in Chamberlain began to fade with the German invasion of Norway, and he resigned on May 10, 1940, the day Germans invaded the Netherlands and Belgium. King George VI asked Churchill to be prime minister, and the Labour and Liberal Parties immediately agreed to join the Conservatives in a wartime coalition government. Said Churchill during his first report to the House of Commons: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.”

Churchill quickly proved to be a skillful prime minister. As commander in chief, he had direct control over the formulation of policy and the conduct of military operations. He and his staff supervised virtually every aspect of the war effort, working closely with the war cabinet secretariat. Through Churchill’s efforts, Great Britain was able to arm itself and prepare for war with remarkable speed.

Churchill assumed power just as the Germans were invading France. The French begged him to send fighter squadrons, but he quickly realized that there was little Britain could do to stop the German war machine in France. In one of his most difficult decisions, he declined France’s request. Great Britain’s planes, he knew, would be needed for his nation’s own air defense.

After the fall of France, Hitler turned his attention to Great Britain. His goal was a land invasion following massive bombing raids designed to weaken Britain to the point of helplessness. It was a dark time for the nation, but Churchill did all he could to protect its suffering populace. His frequent speeches did much to maintain public morale and rally his people to their own defense.

Early in the war, Churchill established a strong relationship with President Franklin Roosevelt, who did much to help the British war effort despite America’s position of neutrality. When the United States officially entered the war in December 1941, the relationship between the two world leaders— based on mutual trust, respect, and admiration—grew closer still. However, as the war progressed and the United States became increasingly powerful, Churchill found himself having to accept American-imposed war plans. His relationship with Roosevelt began to deteriorate, and Churchill’s ideas often went unheeded. In early 1945, for example, Roosevelt ignored Churchill’s warnings about Joseph Stalin’s plans to take over countries in Eastern Europe after the war, with dire consequences.

Churchill Re-elected Following the War

Churchill was re-elected to Parliament in the first postwar election in July 1945, but the Labour Party gained a majority and Churchill, who had run as a Conservative, was replaced as prime minister by Labour leader Clement Richard Attlee. Churchill was at the Potsdam Conference—the last meeting among the United States, Britain, and the USSR—when he received news of the election, and his chair at the conference was taken by Attlee. Churchill was extremely disappointed to be retiring as prime minister, having worked so hard to save the nation from German aggression.

Winston Churchill coined the phrase “iron curtain” during a 1946 speech in Fulton, Missouri. It defined the barrier constructed by the Soviet Union between its Eastern European satellites and the rest of Europe.

Winston Churchill continued to be involved in politics and international affairs. In 1951, his efforts to revitalize the Conservative Party were rewarded when he was again asked to assume the mantle of prime minister. The international nuclear threat was one of his primary concerns, and he tried unsuccessfully to broker a summit conference among the USSR and the Western powers. In 1953, Queen Elizabeth II conferred on him the Order of the Garter, Britain’s highest order of knighthood, making him Sir Winston Churchill. He resigned as prime minister in 1955 but remained a member of the House of Commons.

Churchill continued to write and paint in his retirement, and his paintings were exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1959. He died in 1965, two months after his nintieth birthday and was buried near Blenheim Palace.

Emperor Hirohito

Emperor Hirohito, born in 1901, reigned as emperor of Japan from 1926 until his death in 1989. Revered as divine by his people, he had little to do with the actual governing of his country, his authority stifled by pomp and pageantry. During World War II, he held the title of commander in chief of the armed forces, though almost all military affairs were handled by others.

Hirohito was born in Tokyo, the eldest son of Crown Prince Yoshohito. Beginning in 1914, he was educated at a palace school created to prepare him for his future role as emperor.

Hirohito became the first Japanese crown prince to visit the West when he toured Europe for six months in 1921. During his trip, he expressed great interest in British culture and tradition and was particularly attracted to the concept of a constitutional monarchy as characterized by King George V. When Hirohito became emperor in 1926, he chose to call his dynasty Showa, meaning “peace and enlightenment.”

Under the Japanese constitution of 1889, Hirohito held tremendous authority that derived from the belief that the Japanese imperial line descended from Amaterasu, the sun goddess of the Shinto religion, and had ruled the nation forever. However, Hirohito’s authority was primarily symbolic; he was trained by his advisers to refrain from interfering in political decisions. He remained uninvolved in politics and avoided public controversy, refraining from taking a stand on almost any public issue. In most cases, Hirohito merely approved the policies of his advisers and ministers, which were then adopted in his name.

Because the day-to-day governing of his nation was controlled by militarists, it came as no surprise that Japan instituted an aggressive foreign policy as it sought new sources for needed natural resources. And though Hirohito had little influence on most military issues, he was not completely removed from his nation’s aggression. He approved a number of important Japanese cabinet decisions, including the 1937 invasion of China and the attack on Pearl Harbor. (In an oral autobiography published after his death, Hirohito said he was powerless to stop the militarists because any dissent on his part would have led to his assassination. He also denied knowledge of many of the atrocities committed by Japan during the war, though Western biographers have uncovered evidence that he knew of—and did nothing to stop—the Bataan Death March and the execution of American airmen captured after the Doolittle raid on Tokyo.)

When Emperor Hirohito of Japan died in 1989, he was buried with several of his favorite possessions, including a microscope and a Mickey Mouse watch, which he had received during a 1975 visit to the United States.

Hirohito was as loathed by the Allies as Hitler and Mussolini during World War II, and many people expected the emperor to be tried for war crimes after the fighting was over. However, Allied officials felt it was necessary that Hirohito remain emperor to maintain political calm in postwar Japan, and neither he nor his immediate family (which included many high-ranking military officers) were ever questioned about their involvement in or knowledge of Japan’s wartime activities.

Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo, along with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, personally represented the evil Axis to many people around the world. Though not a dictator like his Axis allies, Tojo ruled the military with an iron fist, and as prime minister was responsible for many of Japan’s strategic successes during the early stages of the war.

Tojo was born in Tokyo in 1884, the son of an army general. He attended the Imperial Military Academy and then the Army Staff College, from which he graduated at the top of his class in 1915. From 1919 to 1922 he was a military attaché in Switzerland and Germany, and in the late 1920s he served in a section of the Army General Staff, monitoring mobilization preparations for full-scale war.

In the early 1930s, Tojo joined a group of officers known as the Control Faction, which was devoted to updating and modernizing the Japanese army, with an emphasis on military technology. However, his association with the group was viewed unfavorably by an opposing faction, and Tojo was punished with a series of posts far below his status and ability. His career took a turn for the better after 1935 when he was sent to Manchukuo, the puppet state established by the Japanese in Manchuria. Tojo eventually became the chief of staff of the Kwantung Army, the primary Japanese military force in the region.

While in Manchukuo, Tojo became known for his efficient and decisive manner and his aggressiveness as a staff officer. A tough disciplinarian, he was secretly called “The Razor” by his men. Tojo was ordered back to Tokyo in 1938 to serve as vice minister of war, and in 1940 he was promoted to war minister. He closely watched the war in Europe and became convinced that Germany would eventually triumph. In the fall of 1940, he actively supported an official alliance with Germany and Italy, making Japan the third member of the Axis triad.

Tojo strongly advocated Japanese expansion into East Asia through military force and the establishment of a regional co-prosperity sphere under Japanese control. When relations between Japan and the United States worsened in 1941 as a result of Japanese aggression, Tojo held firm, opposing any compromise that would undermine Japan’s position in East Asia. By the fall of 1941, it appeared that Japan would have no choice but to enter the world war. Tojo, widely viewed by many as a man who could guide Japan to victory, was named prime minister in October. In December 1941 his cabinet decided to declare war on the United States by attacking the American naval base at Pearl Harbor.

Tojo’s scope of authority widened over the course of the war. While retaining his position as war minister, he became head of the Munitions Ministry in 1943 and took over as army chief of staff in 1944.

Tojo’s political power began to wane as Allied victories over Japan became increasingly common toward the end of the war. Forced to resign as prime minister in July 1944 when the United States took the island of Saipan (thus placing Japan within range of Allied bombers), Tojo remained in retirement for the rest of the war.

In September 1945, Tojo tried to commit suicide when he learned that he was to be arrested and tried for war crimes. After his recovery, he was tried as ordered by the International Military Tribunal in Tokyo and found guilty. He was hanged in December 1948.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

During his unprecedented twelve years in office, Franklin D. Roosevelt faced national and international problems whose severity had not been seen since the presidency of Abraham Lincoln. It’s a testament to Roosevelt’s skill as a leader and a politician that he was able to successfully guide the nation— and the world—through these troubling times.

When Roosevelt was elected as the thirty-second president in 1932, the nation was well into the most devastating economic depression it had ever experienced. And nine years later he would be forced to ask Congress to thrust the United States into a war that would eventually envelop most of the world. No political weakling like many of his immediate predecessors, Franklin Roosevelt mustered all of his strength and courage to keep the world free from tyranny.

Franklin Roosevelt was born on his family’s estate in Hyde Park, New York, on January 10, 1882. His father, James, was a successful businessman with a variety of interests, and his mother, Sara, was a prominent member of New York society. The family, conservative Democrats by belief, was deeply involved in politics and had already produced one president: Franklin’s cousin, Theodore Roosevelt.

Political Career

Roosevelt entered politics in 1910 when he ran for the New York State Senate. He campaigned vigorously and won by a narrow margin. In Albany, he developed a reputation as an independent scrapper who followed his own ideals rather than the desires of the more established Democratic leadership. He quickly became known as a social and economic reformer and was re-elected in 1912—despite his inability to actively campaign because of a case of typhoid fever. Much of Roosevelt’s political success must be attributed to his association with Louis McHenry Howe, a journalist and savvy political strategist who knew how to promote Roosevelt’s career with maximum effectiveness.

Roosevelt managed to make a name for himself in national politics even before his state senate re-election by assisting in Woodrow Wilson’s presidential campaign. When Wilson took the White House in 1912, Roosevelt was rewarded for his hard work with an appointment as assistant secretary of the navy. Roosevelt resigned his state senate seat and moved to Washington, D.C.

Roosevelt served as assistant secretary of the navy until 1920. He came to understand how Washington worked and how to manipulate the system to get things done, so when the United States entered World War I in 1917, the navy was ready and able to leap into action. Roosevelt’s position required him to make frequent public speeches, which helped establish his image as a politician with a tremendous future. Roosevelt resigned his Navy Department post in 1920 to campaign for the vice presidency under Democratic presidential candidate James Cox, but they were defeated by Republicans Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge.

In August 1921, Roosevelt was diagnosed with poliomyelitis (polio). In pain and no longer able to walk, Roosevelt might have thought that his political career was destined to end before it had really begun. His mother urged him to retire to Hyde Park and enjoy the peace and quiet there, but encouraged by both his wife, Eleanor, and Louis Howe, Roosevelt refused to let his illness keep him down. Though primarily confined to a wheelchair, he remained active, maintaining important political contacts and slowly rebuilding his career.

Franklin Roosevelt was very rarely photographed in a wheelchair or walking with the leg braces and canes he required, and the press almost never discussed his disability. As a result, many Americans remained unaware for years that Roosevelt was paralyzed from the waist down.

Throughout much of the 1920s, Roosevelt worked with Al Smith, helping him win his second term as governor of New York and later assisting with Smith’s presidential campaigns. In 1928, at Smith’s encouragement, Roosevelt ran for governor of New York, winning by a very slim margin. Smith, meanwhile, lost the presidency to Herbert Hoover. The following year, the United States slipped into a crippling economic depression when the stock market crashed, taking with it the fortunes of thousands of Americans and forcing the closing of many banks. In 1930, Roosevelt was re-elected governor of New York—a position that would quickly help him reach the White House.

Roosevelt Becomes President, Introduces the New Deal

As a result of his aggressive personality, his reputation as a social reformer, and his strong New York roots, Roosevelt was a natural for the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination. He worked vigorously to hold on to his status as party favorite and was nominated on the fourth ballot. In his acceptance speech, Roosevelt promised the American people a “new deal” that would help alleviate many of the social and economic ills forced on them by the Depression. He campaigned strongly, making numerous speeches throughout the country, and ultimately took forty-two of the nation’s forty-eight states.

Roosevelt’s first concerns were with helping the millions of Americans who were suffering as a result of the Depression. He instituted a number of domestic reforms, bringing the government more directly into people’s lives than ever before. During his first 100 days in office, Roosevelt and Congress worked together to pass more bills than any previous administration had done in a similar time span. The Emergency Banking Act, which was introduced, passed, and signed by the president in just one day, gave the federal government remarkable power to deal with the banking crisis that had economically crippled the nation.

Roosevelt also worked hard and fast on relief legislation designed to temporarily assist out-of-work Americans while getting them back into the work force as quickly as possible. Under Roosevelt’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), large amounts of money were given to the states to assist those most in need.

Nearly one-sixth of the nation was still on government relief by the end of 1934. In 1935, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was established by executive order and the FERA was abolished. The WPA (later renamed the Work Projects Administration) helped the nation by building or repairing roads, schools, libraries, and government buildings. Roosevelt also established the Civilian Conservation Corps to assist unemployed and unmarried young men and the National Youth Administration, which gave part-time jobs to needy high school and college students.

Roosevelt was a strong advocate of government-sponsored social and economic change. His administration enacted reform legislation that increased the federal government’s regulatory activities as well as important banking legislation designed to bolster the flagging dollar.

Re-elections

Roosevelt did much to help the American people during his first term in office, and he was re-elected in 1936 with more than 60 percent of the popular vote. However, middle-class support for the Roosevelt administration began to erode in 1937 and 1938, primarily because of its support of increasingly militant labor unions. Roosevelt’s armor also lost some of its sheen when he unsuccessfully tried to increase the size of the Supreme Court. The president argued that the change was needed to facilitate the high court’s work, but in truth, Roosevelt hoped to pack the court with members who better supported his progressive program. Then, in 1937, the president cut spending to balance the budget, causing the Depression to worsen and further tarnishing Roosevelt’s reputation.

Roosevelt scored better with his foreign policy. He instituted the Good Neighbor policy toward Latin America, which meant that the United States would no longer intervene in Latin America to protect private American interests. Later, he requested a huge government appropriation for naval expansion, then asked for yet more money to bolster American defense. After war broke out in September 1939, he called a special session of Congress to revise the Neutrality Act so that nations at war against Germany could buy arms on a cash-and-carry basis. Then, after his re-election in 1940, Roosevelt worked around national isolationist policies through congressional passage in March 1941 of the Lend-Lease Act, which allowed the United States to militarily aid Great Britain and other nations without actually having to declare war on Germany and Italy. Roosevelt’s goal was to provide yet more aid to Great Britain and France, though deep in his heart he knew the United States was headed toward war whether it wanted to or not.

Entering the War

America entered World War II on December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Roosevelt found himself in the dual position of commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces and soothing father figure to the American people. Historians have long debated Roosevelt’s effectiveness during the war years, though most agree he was a strong national and international figure who understood that the only way to protect the United States was to drive Germany and Japan into unconditional surrender.

Roosevelt was, for the most part, admired and respected by the other Allied leaders with whom he was aligned. Though the United States was slow to enter the conflict in Europe, once it was involved, Roosevelt offered everything in the American arsenal and then some. He consulted often with other world leaders and helped ease the hurt feelings and international misunderstandings that were sure to accompany a war effort of such remarkable scope.

Figure 7-2 President Roosevelt receives a Red Cross pin from a young volunteer.

Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (ARC 196055)

Roosevelt’s stint as assistant secretary of the navy under Wilson served him well during this period. Most historians agree that he ably directed the course of the war and worked closely with his Joint Chiefs of Staff in making important decisions. Very often, Roosevelt’s final decisions went against those of his military advisers as he attempted to balance both military and political concerns. Examples include the decision to invade North Africa, the plan for Douglas MacArthur to retake the Philippines, and the decision to continue sending Lend-Lease ships to the Soviet Union.

Extraordinary Challenges

Roosevelt’s job as commander in chief was extraordinarily difficult. At the beginning of the war, he found himself in the unenviable position of having to dramatically increase military production without creating inflation, and he had to oversee the allocation of goods throughout several theaters of war and to the various Allied powers. In addition, Roosevelt oversaw the immediate buildup of the nation’s army and navy, recruiting servicemen (and women) and increasing production of needed materiel. Lastly, he had to stay in constant contact with the American people, explaining his decisions and their importance in ways that the average American could understand and support. Thankfully, this was a skill at which Roosevelt was adept. His frequent radio addresses, known as “fireside chats,” helped calm a frightened populace during its most desperate and dire hours.

Franklin Roosevelt was the only president to be elected to four terms in office—and the only president who will ever hold such an honor. The Twenty-second Amendment to the Constitution, adopted after his death, limits a president to two elected terms.

Though Franklin Delano Roosevelt saw the United States into its second world war and worked tirelessly to support it, he died before an Allied victory could be achieved. The war took a terrible toll on his health, and he looked old and frail while campaigning for his fourth term. He defeated Thomas Dewey in 1944, and in the early spring of 1945, Roosevelt traveled to his vacation home at Warm Springs, Georgia, in an attempt to rebuild his strength. On April 12, Roosevelt complained of a severe headache; he died a short time later from a massive cerebral hemorrhage. Vice President Harry Truman took the oath of office later that day to become the nation’s thirty-third president.

Charles de Gaulle

Though forced to flee to Great Britain with the fall of France in 1940, Charles de Gaulle was not about to give up on his beloved country. Over the objections of Winston Churchill, he established a Free French movement that helped to liberate the nation.

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was born in Lille, France, on November 22, 1890. The son of a teacher, he attended the Saint-Cyr Military Academy, graduating in 1912. An infantry officer during World War I, de Gaulle was wounded three times and eventually captured by the Germans. After the war, he was appointed aide-de-camp to Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain. During this period, de Gaulle became a true student of war, conceiving doctrines and plans that conflicted with established military articles of faith. In his book The Army of the Future, de Gaulle recommended lightning-swift movements and use of armored forces that very closely mirrored Hitler’s blitzkrieg strategy.

When the war in Europe began in September 1939 with the German invasion of Poland, de Gaulle was commander of tanks in the French Fifth Army. However, under the French army command structure, it was outside de Gaulle’s authority to actually place the tanks into action. After Germany raced through Poland, de Gaulle requested—and was granted—command of an armored division. His division engaged the Germans in one of France’s few offensives in Germany’s campaign against France and the Low Countries.

Charles de Gaulle had a strong sense of self-purpose. While he was attending military school, a fellow student commented, “I have a curious feeling that you are intended for a very great destiny.” To which de Gaulle replied, “Yes. So have I.”

On June 6, 1940, de Gaulle was named undersecretary of state to the minister of national defense and war. Three days later he flew to London to meet with Prime Minister Winston Churchill about coordinating the strategy of the two nations’ armies. But when de Gaulle returned home, he found the government on the verge of fleeing. He pleaded with Prime Minister Pétain to stay and fight or at least to evacuate troops to French North Africa and take a stand there.

But de Gaulle’s pleas fell on deaf ears. By that point, France was on the verge of surrender, its army no match for the German juggernaut. De Gaulle returned to Great Britain, and in an address to his countrymen broadcast across the channel by the BBC he stated, “France is not alone!” The collaborationist Vichy government charged de Gaulle with treason and condemned him to death. Unbowed, de Gaulle formed a government-in-exile force known as the Free French movement, which later became the Free French National Council.

Later, de Gaulle aligned himself with General Henri Giraud in French North Africa, where another freedom movement had developed, becoming copresident with Giraud of the French Committee of National Liberation. After the crafty de Gaulle was able to facilitate Giraud’s departure, he became the leader of both the French Resistance movement in German-occupied France and the Free French in North Africa.

Shortly before the start of the Normandy invasion, de Gaulle demanded that his provisional government be declared the rightful government of all liberated areas in France. General Dwight Eisenhower was able to placate de Gaulle by promising not to accept any ruling government except de Gaulle’s and by making de Gaulle supreme commander of the French armed forces. On August 26, 1944, a triumphant de Gaulle rode into newly liberated Paris behind French and American troops.

At the war’s end, de Gaulle was elected interim president of the provisional government by a newly elected constitutional assembly. He tried desperately to make France a part of the postwar planning but was rebuffed by Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin.

De Gaulle resigned as provisional president on January 20, 1946. He returned to politics in 1958 and was elected president of the newly created Fifth Republic under a revised constitution. He held the position until 1969, when he resigned after defeat in a national referendum. He retired to his estate in Colombey-les-deux-Églises, where he worked on his memoirs until his death in 1970.

Joseph Stalin

Few Allied leaders were as controversial as Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. A valued ally in the war against Germany, Stalin quickly became the enemy by making a grab for much of Eastern Europe once the war was over.

Stalin was born Joseph Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili on December 21, 1879, in what would later become the Soviet Republic of Georgia. His father was a cobbler and his mother a house cleaner. In 1888, Stalin entered the Gori Church School. He was an excellent student and won a scholarship to the Tbilisi Theological Seminary. It was there that he was introduced to the political philosophies of Karl Marx, which caused him to rethink his dedication to the church. Because of his involvement with the underground revolutionary movement to overthrow the monarchy, Stalin was expelled from the seminary in 1899. Soon, he was arrested for distributing illegal literature (primarily Marxist propaganda) to rail workers and others, and was eventually exiled to Siberia. However, he managed to escape and returned to Georgia in 1904.

He took the name of Stalin (“man of steel”) and eventually joined the Bolsheviks, who were being led by Vladimir Lenin. He married in 1905 (his wife, Yekaterina, died two years later). Between 1908 and 1912, Stalin was arrested several times but managed to escape. In 1912, he traveled to St. Petersburg (later Petrograd and then Leningrad) and joined the staff of a small newspaper titled Pravda (Truth), later the official Communist newspaper of the USSR. It was then that Stalin was encouraged by Lenin to write his primary theoretical work, Marxism and the National Question. In 1913, Stalin was arrested again and sentenced to life in exile. This time, he was not able to regain his freedom until the revolution of 1917 that instituted Communist rule.

Communist Takeover of Russia

Free again, Stalin traveled back to Petrograd, where he became deeply involved in the workings of the Bolshevik government and became a member of the party’s Central Committee bureau. In 1919, he was elected to the Politburo, the Communist Party’s highest decision-making body. As a political commissar in the Red Army during the Russian Civil War, he oversaw military activities against the counterrevolutionary White forces led by General Piotr Wrangel.

Stalin was elected general secretary of the Communist Party in 1922, which helped solidify the base of his political power. Aggressive by nature, he often clashed with Lenin, who came to regret his association with Stalin. Lenin eventually called for Stalin’s removal from office, but Stalin was able to hold on to his position through slick political maneuvering. After Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin used political connections, strategic alliances, and good old-fashioned back-stabbing to establish and maintain his power. By 1929, he had become the supreme ruler of the USSR.

Stalin as Supreme Ruler

A brutal and vicious leader, Stalin carried out a number of purges throughout the 1930s to eliminate anyone who might oppose him. His purge of the Red Army just before the onset of World War II removed nearly a third of the officer corps, hampering the nation’s ability to defend itself early in the conflict.

Stalin would continue his campaign of terror throughout his life, sending as many as 25 million of his own people to squalid prison camps in Siberia before his death in 1953. People could be exiled to prison for virtually anything, causing the entire nation to tremble in fear under his iron-fisted rule. During World War II, Stalin sentenced his soldiers to prison camps for the crime of being captured by the Germans.

Entering the War

Though ideologically opposed to Nazism, Stalin saw value in aligning with Hitler, and in August 1939 the two leaders signed a nonaggression pact that essentially gave the Soviet Union a piece of Poland. However, Hitler turned on his ally and invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. The move stunned Stalin, who seemed unable to make a decision for the first few weeks of the German campaign in the Soviet Union.

Stalin’s unwillingness to prepare for a German invasion despite overwhelming evidence that it was coming and the poor condition of the Red Army meant quick victories for Hitler and placed the Soviet Union in a desperate defensive position.

Stalin guided the Soviet war effort from a bomb shelter deep below the Kremlin, directing his generals and rallying his people against the German invaders. Though Stalin was a vicious dictator who had ordered the deaths of millions, the Soviets looked to him to protect them from Hitler.

When the United States entered the war in December 1941, Stalin began pushing for a second front, arguing that a U.S.–British invasion of German-occupied Europe would help take some of the pressure off the Soviet Union. Stalin also demanded supplies from his Allied brethren, threatening to sue for a separate peace with Germany if help was not forthcoming.

When Stalin addressed his people on the radio in November, he offered fictitious statistics suggesting that the Red Army had the enemy on the run. In truth, it was the other way around: Soviet forces were taking a pounding. Stalin’s lies were the result of concerns that the populace of the conquered territories would rise up against him.

Stalin met with Roosevelt and Churchill for the first time at the Tehran Conference in November 1943. By then, the Germans had pulled most of the way out of the Soviet Union and the Soviet offensive had begun. Sensing an Allied victory in Europe, Stalin plotted to gain control of as much territory as he could after the war. Months later, Stalin began his land grab by demanding concessions on Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe in exchange for a promise to declare war on Japan. Soviet participation in the war against Japan lasted all of five days; for his effort, Stalin was allowed to extend his influence into northern Korea, Manchuria, and the Kuril Islands.

The Start of the Cold War

With World War II over, Stalin immediately began his efforts to spread Communism around the world, resulting in icy relations with the Western powers. The Cold War was quick in coming, and it would last for decades.

Stalin’s mental abilities began to deteriorate about 1950, and he was seen less and less around the Kremlin. His paranoia growing, Stalin ordered another purge in January 1953, this one aimed at Kremlin doctors who Stalin thought were plotting against high-level Soviet officials. Stalin died from complications of a stroke in March, just before his latest round of terror could begin. He was succeeded as general secretary of the Soviet Communist party by Nikita Khrushchev.

Harry S Truman

Truman had served as vice president under Franklin D. Roosevelt for less than three months when Roosevelt’s death thrust Truman into the presidency. His administration would be rife with controversy, but the stalwart Missourian never backed away from the rigors of high office, and he assumed responsibility for all the decisions made by his administration. A small plaque on his desk confirmed Truman’s conviction: “The buck stops here.”

Truman was born on May 8, 1884, in Lamar, Missouri, the oldest child of John and Martha Truman. When he was six years old, his family moved to Independence, Missouri. It was there, while attending Sunday school at the local Presbyterian church, that Truman met five-year-old Bess Wallace, the girl who would later become his wife.

Political Beginnings

In need of a job, Truman turned to Mike Pendergast, organizer of the Democratic club Truman had belonged to years earlier, for permission to enter a four-way Democratic primary for an eastern Jackson County judgeship. Pendergast okayed Truman’s entry but refused to endorse him. Truman campaigned on his war record and his deep Missouri roots, and he won both the primary and the general election. He was sworn into his first public office in January 1923.

When Truman’s term was up, he hoped for renomination in the Democratic primary, but the influential Ku Klux Klan had other ideas. Almost as quickly as he had entered politics, Truman was out. For the next two years, he sold automobile club memberships and dabbled in banking.

Harry Truman’s middle initial doesn’t stand for any name. It was given to him when he was born to honor both of his grandfathers.

In 1926, Truman sought a four-year term as presiding judge of the county, a position that oversaw county roads, buildings, and taxes. This time, Truman was supported by Pendergast, who was boss of the local political machine. Most political machines maintained power and influence by rewarding supporters with lucrative government jobs, but Truman—never one to mince words—told Pendergast he would immediately fire anyone who wasn’t doing his job. Truman won the position and immediately set about correcting the problems caused by years of graft and political cronyism. His hard work paid off with a second easily won four-year term.

Truman Joins the Senate

After his stint as county judge, Truman was asked by Pendergast to run for the U.S. Senate. Truman campaigned vigorously, capitalizing on the popularity of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and beat his Republican opponent by a large margin. However, his stint in the Senate got off to a bad start. Despite his honesty, Truman’s association with the Pendergast political machine tainted him, and some believed that he would be implicated in the government’s investigation of the Pendergast organization. Truman managed to salvage his political career by impressing two important men: Vice President John Nance Garner and Arthur Vandenberg, the Republican senator from Michigan. With their assistance, Truman was named to two important Senate committees, where his political savvy was a valued asset.

Truman was challenged for his Senate seat in 1940 by two influential Missouri Democrats who had worked to bring down the Pendergast machine. He was the odd man out in the race, hampered by a lack of both money and big-name support. Still, he decided to make his best effort, canvassing the state and talking to the people in terms they could understand. Truman won the general election, and when he returned to the Senate, he received a standing ovation from his colleagues, many of whom were startled by his victory.

As the United States geared up for war in 1941, Truman began investigating allegations of waste in the defense program. He toured the camps and defense plants and found conditions that he called appalling. When he returned to the Senate, he denounced the defense program and demanded a full investigation. His colleagues agreed and put him in charge of the investigating committee.

The Truman committee spent the next two years investigating the defense program and producing detailed reports confirming allegations of fraud and waste. With a budget of just $400,000, the committee managed to save the nation an estimated $15 billion. The committee’s success also served to make Harry Truman a national figure, and leading Democrats started mentioning his name as a contender for the 1944 vice presidential spot under Roosevelt.

The Call for a Strong VP

Few people doubted that Roosevelt would run for a fourth term in 1944, though Democratic leaders were increasingly troubled by his failing health. The need for a strong vice presidential candidate became paramount. At the Democratic convention, Truman was elected on the second ballot; together, he and Roosevelt won the election.

Truman had been vice president for just eighty-two days when Roosevelt died, in April 1945. He spent his first month as president meeting with Roosevelt’s aides and advisers in an attempt to get up to speed on the war effort and to ensure the continuation of Roosevelt’s plans and programs. As the Allies pushed into Germany and victory in Europe seemed guaranteed, Truman insisted that unconditional surrender was Germany’s only option. V-E Day (Victory in Europe Day) was announced on May 8, 1945: Truman’s sixty-first birthday.

From July 17 to August 2, Truman attended the Potsdam Conference in Germany along with Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill (with Clement Attlee succeeding Churchill as British prime minister during the conference). The men discussed how best to implement the decisions reached at the previous Yalta Conference regarding the reconstruction of Europe after the war. As presiding officer, Truman suggested the establishment of a council of foreign ministers to oversee peace negotiations, settlement of reparations claims, and war crimes trials.

Figure 7-3 Harry S Truman and Winston Churchill at the Potsdam Conference, 1945.

U.S. Army, courtesy of Harry S Truman Library (ARC 198808)

Truman, backed by the other Allied leaders, issued the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, calling for Japan’s unconditional surrender and listing peace terms. Ten days earlier, the first successful atomic bomb had been detonated near Alamogordo, New Mexico. The use of such a bomb, Truman’s military advisers told him, could help prevent the loss of up to 500,000 American servicemen should the Allies be forced to invade the Japanese mainland. When Japan ignored the ultimatum set forth in the Potsdam Declaration, Truman authorized the use of the bomb, which was dropped on the city of Hiroshima on August 6. Two days later, Stalin sent troops into Manchuria and Korea, and a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki the day after that. Japan laid down arms on August 14 and officially surrendered on September 2.

Following the War

With the war over, Harry Truman turned his attention to converting the United States back to a nation at peace. However, many of his proposals received tremendous opposition from Congress, which felt he was trying to attain too much too soon. Controversy over his domestic policies followed Truman for much of the rest of his first term.

The end of World War II did not mean an end to international tension. The USSR, once America’s ally, quickly became a feared enemy as it tried to take control of much of Eastern Europe. Truman vehemently opposed Stalin’s actions, and both sides quickly broke wartime agreements. The ensuing hostility between the two world superpowers blossomed into what became known as the Cold War.

Truman was re-elected president in 1948, campaigning on a platform of civil rights and other social issues that angered Southern Democrats. The race was exceptionally close, and most people thought Republican candidate Thomas Dewey would win. The Chicago Tribune, in its belief that Truman would lose, ran the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” on the front page of its early edition on November 2. However, when the votes were finally tabulated, Truman had won by nearly 2 million votes.

In 1950, Harry Truman survived an assassination attempt that killed a White House guard.

After his second term, Truman retired to his home in Independence, Missouri. He remained active in national and regional politics, though his influence had waned, and loyally supported the Democratic presidential candidates in subsequent years. He wrote memoirs and other books, and toured colleges and universities, lecturing on American government. Harry Truman died in 1972 and was buried on the grounds of the Truman Library in Independence.