Adolf Eichmann

At the end of World War II, few names evoked as much revulsion as did that of Adolf Eichmann, one of the primary architects of the so-called Final Solution and the man ultimately responsible for the deaths of millions of Jews in Nazi-occupied nations.

Eichmann became an early supporter of Hitler and the Nazi movement. Under the guidance of Austrian Nazi official Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Eichmann became one of the Nazis’ foremost “authorities” on Jews.

Figure 9-1 Adolf Eichmann.

Getty Images/David Rubinger/Contributor

Eichmann knew how to play politics and quickly became chief of the Reich Central Office of Jewish Emigration. In 1940, he was instructed to develop a plan to deport 4 million Jews to Madagascar, which was controlled at the time by the Vichy French. The plan never came to fruition because the Nazis found it easier to imprison and kill the Jews than to move them out of the country.

In January 1942, Eichmann attended the Wannsee Conference on the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question,” which involved discussion of the most effective ways to eliminate large numbers of people. Eichmann’s notes on the genocide conference were recovered after the war and used as evidence at the Nuremberg war crimes trials. Throughout the war, Eichmann authorized the deportation of countless Jews to concentration camps and supervised the SS action groups.

Eichmann managed to slip away from the authorities and escaped from Germany before he could be tried. Eichmann was finally located in Buenos Aires in May 1960 and secretly returned to Israel. Eichmann tried to convince the court that he had merely been following orders. His pleas fell on deaf ears. Eichmann was found guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against the Jewish people, and was hanged on May 31, 1962.

Eichmann was one of numerous high-ranking Nazis who were tried for war crimes. He apparently felt no remorse for his actions. According to an associate, as Allied forces bore down on Berlin, Eichmann said he would leap laughing into the grave because the feeling that he had been instrumental in the deaths of 5 million people would be for him a source of extraordinary satisfaction.

Joseph Goebbels

The Third Reich flourished under a constant bombardment of public propaganda— almost all of it the work of Nazi Party propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels. Goebbels understood very well the impact and influence of the right image, and early on he designed and orchestrated an ongoing media campaign that emphasized Hitler’s importance as the Führer and the 1,000-year reign of the invincible Third Reich.

In 1933, Hitler appointed Goebbels minister of propaganda and public enlightenment and gave him the task of providing Germany with “spiritual direction.” This meant complete government control of every form of media. Almost immediately, every book, radio program, newspaper, and motion picture became imbued with Nazi rhetoric. Opposing viewpoints were censored.

Goebbels was a slight, sinister-looking man who walked with a noticeable limp. He joined the Nazi Party in 1925 and was soon writing its propaganda leaflets. In 1926, Hitler made him district leader in Berlin, where he displayed an innate talent for turning political rallies into outright brawls against any group (but particularly Communists) that disagreed with the Nazi doctrine.

Goebbels was rapidly promoted to be Hitler’s political manager, and it was here that his talents as a propagandist came to the forefront. Under Goebbels’s direction, political rallies became impressive multimedia events complete with huge posters, documentary films, loudspeakers, and massive crowds of faithful supporters. The swastika—the Nazis’ grand symbol—was clearly visible throughout.

Hitler rewarded Goebbels’s devotion in 1944 with a promotion to the post of Reich trustee for total war. Goebbels took the title to heart and during the final days of the Reich endorsed Hitler’s wish that Germany go down in flames rather than submit to its invaders. As the Allies approached, he read to Hitler from his favorite books and continued to feed the Führer’s demented ego.

On May 1, 1945—the day after Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide— Goebbels and his wife, Magda, ordered Hitler’s dentist to give their five children a dose of morphine. Once the children, ranging in age from three to twelve, were asleep, Goebbels placed cyanide capsules in their mouths. He and Magda then walked into the Chancellery garden, where Hitler’s charred remains were still evident, and ordered an SS underling to kill them. They were both shot in the back of the head; then their bodies were doused with gasoline and set afire. That night, the entire Führerbunker was torched, incinerating all that lay within.

Heinrich Himmler

Few men were as feared within the Nazi regime as Heinrich Himmler, leader of the Nazi secret police known as the SS. A Bavarian chicken farmer before joining Hitler and rising through the ranks of the Nazi Party, Himmler was responsible for some of the Nazis’ most heinous activities, including the creation of concentration camps and the mass slaughter of “inferior” individuals, specifically the Jews, the physically infirm, and the mentally handicapped.

Himmler was an early supporter of Hitler and his National Socialist German Workers’ Party. Originally commander of political police in Bavaria, he worked his way up through the party until he was second only to Hitler in power and authority.

Himmler firmly agreed with Hitler’s desire to rid Germany of inferior people, and one of his first tasks was the creation in 1933 of the Dachau concentration camp, which was originally built to house dissidents. A year later, Himmler cemented his power within the Nazi Party with the orchestration of the “Night of Long Knives,” a rapid series of assassinations that eliminated the increasingly powerful SA police apparatus and replaced it with the SS. Himmler put the SS in charge of Dachau, and the dreaded agency oversaw all concentration camps and death camps throughout the war.

When Germany went to war in 1939, Hitler appointed Himmler commissar for consolidation of German nationhood. As the title suggests, Himmler’s job was to purify Germany by eliminating all “undesirables,” “misfits,” and “inferior races.” Over the next several months, he supervised the forced eviction of Poles so their land could be taken over by ethnic Germans, ordered the systematic murder of concentration camp inmates at Auschwitz, and instigated the slaughter of hundreds of sick and starving civilians in the Warsaw ghetto. Himmler also was said to have established a program in which unwed German women could bear the children of pure Aryan soldiers on their way to battle.

In August 1943, Himmler was made minister of the interior, which placed him in complete charge of all concentration camps. His duties also included forcing the residents of conquered nations to work in German war factories and authorizing horrifying medical experiments on concentration camp inmates. In addition, Himmler established special action groups designed to enter conquered territories specifically to eliminate the Jewish population.

Himmler tried to escape Germany in disguise as the Allies entered Berlin, but he was captured by British troops near Bremen. Facing trial for war crimes, Himmler took his own life by poison on May 23, 1945.

Himmler’s SS was instrumental in uncovering and rounding up the conspirators of the failed assassination plot against Hitler in July 1944. Hitler was pleased with Himmler’s work and rewarded him by placing him in command of the reserve army Hitler had formed to make one last desperate offensive against the approaching Allied forces. However, the offensive was a failure, and Germany was soon in ruins. In the spring of 1945, Himmler tried to broker a peace settlement through the Swedish Red Cross, but his efforts were unsuccessful. Hitler found out about Himmler’s “treason” and, in one of his last acts before committing suicide, expelled Himmler from the Nazi Party and stripped him of all authority.

Rudolf Hess

The saga of Rudolf Hess is a strange one indeed. A devoted follower of Hitler from the very beginning, Hess had a tremendous future in the Nazi Party. Then, in 1941, he threw it all away by flying to Scotland in a cockeyed attempt to work out an unauthorized peace treaty. The stunt landed him in prison for the rest of his life.

Hess and Hitler served in the same infantry regiment during World War I, and it was there that they forged a strong friendship. After the war, Hess became enamored of Hitler’s political rhetoric and joined the Nazi Party. He was by Hitler’s side during the ill-fated Beer Hall Putsch in 1923 and went to prison with the future Führer. While incarcerated, Hess transcribed and edited much of Hitler’s autobiography, Mein Kampf.

When Hitler’s political career started to take off, he made Hess his personal aide. In 1933, when Hitler assumed the position of chancellor, he made Hess deputy führer. Six years later, on the eve of World War II, Hess became a member of the Ministerial Council for the Defense of Germany and the third most powerful man in the German government, after Hitler and Hermann Goering.

During the Olympic Games in 1936, Hess had made the acquaintance of the Duke of Hamilton. When war broke out in Europe, Hess wrote the duke a letter—apparently without Hitler’s knowledge—inquiring about the possibility of a peace treaty between Great Britain and Germany. The British government told the duke to ignore the letter.

Hess and six other convicted Nazis were incarcerated at Spandau Prison in western Berlin. Hess’s fellow prisoners either died or were released over the years, and by 1966 he was the prison’s sole inmate. Hess remained in Spandau until his death in 1987, at which time the prison was torn down.

But Hess wasn’t about to be put off. With the help of aviator Willy Messerschmitt, he learned how to fly a fighter plane and took off, unarmed, for the Duke of Hamilton’s estate on May 10, 1941. When he got lost, Hess bailed out over Scotland and was promptly taken into custody by British authorities, who thought he was crazy.

When Hitler found out what had happened, he flew into a rage, instantly removing Hess from the Nazi Party. The British held Hess in the Tower of London for the rest of the war. At the war’s end, he was tried for conspiracy to commit crimes and for crimes against humanity. Hess pretended he had amnesia but did not convince the tribunal, which sentenced him to life in prison.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and niece of President Theodore Roosevelt, was a prominent figure during World War II. Not content to observe the war from the White House, she did much to improve the morale of her fellow countrymen and the troops overseas.

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was born on October 11, 1884, to Elliott and Anna Hall Roosevelt. Both of her parents died by the time she was ten, and she lived with her maternal grandmother until being sent to a boarding school in Great Britain at age fifteen. When she returned home, Eleanor did social work in New York until she married her distant cousin, Franklin Roosevelt.

Eleanor played the role of faithful wife while Franklin pursued his political career, but their relationship changed drastically when she discovered that he had been having an affair with her social secretary. The couple reconciled, but Eleanor decided that she no longer wanted to be simply a housewife and started to pursue outside interests, including the League of Women Voters and the Women’s Trade Union League. When Franklin was crippled by polio, she helped keep his political career alive by becoming active in the Democratic Party. When her husband assumed the presidency, Eleanor often acted as a springboard for his programs and proposals.

During World War II, Eleanor Roosevelt often donned a Red Cross uniform and visited wounded servicemen in military hospitals throughout the United States and overseas. During one trip, she traveled a remarkable 25,000 miles in just five weeks. After she returned home, she spent countless hours making hundreds of reassuring phone calls to the concerned parents, wives, and girlfriends of the servicemen she had met. She also championed the cause of desegregation in the military.

Eleanor Roosevelt served as a member of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations from 1945 to 1953 and chaired the commission that created the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. She died in New York City on November 7, 1962.

Chiang Kai-shek

One of two important Chinese leaders during the years of Japanese aggression and occupation was Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Kuomintang and of the Republic of China. Chiang inherited the mantle of government from Sun Yat-sen and was in charge of the country’s rebuilding for a time, but was soon faced with two enemies: Japan and the Communists. Under the slogan “first internal pacification, then external resistance,” Chiang led a significant armed force against the Communist forces, under Mao Tse-tung. This internal struggle cost China many men and much momentum in the early years of the Japanese invasion. However, by 1937, the two bitter rivals had agreed, at least on the surface, to put aside their differences and fight a common foe.

Years of bitter fighting between the Chinese and Japenese followed, with horrendous casualties on both sides, but especially Chinese forces. China lost 200,000 in the capture of Shanghai alone. Another 300,000 died in the Rape of Nanking. Chinese soldiers resisted Japanese aggression as much as possible. The country received a large amount of aid from the Allied powers, especially the United States, which sent the famous Flying Tigers to beef up China’s air defenses. China also provided landing space to those pilots who were lucky enough to escape after dropping bombs on Japan in James Doo-little’s famous raid.

Chiang emerged as the national leader and a friend of the Allied powers, who made him one of the “big four” and invited him to the historic Cairo Conference in 1943. He remained the nominal leader of the country after the Japanese surrender but soon lost his position in the Communist Revolution. Chiang fled China for Formosa (Taiwan) in 1950 and ruled there until his death in 1975.

Marshal Philippe Pétain

Philippe Pétain had quite a dichotomous reputation, going from one of France’s military heroes to one of its most villainous personalities. A hero of World War I known as the “Savior of Verdun,” Pétain gradually and reluctantly assumed more powerful roles in the French government. As France’s secretary of state, he urged appeasement of Germany and later signed the armistice that handed over control of much of the country to the Germans.

During the rest of the war, Pétain was the head of the Vichy government and provided much food, land, and war materiel to the Axis cause. His willingness to help the Nazi cause waned as the war went on, and he eventually lost his dictatorial powers as the Germans assumed greater control. Pétain was vilified for his actions by Charles de Gaulle and other leaders of the Free French.

After the war, Pétain was seized and named a traitor to his people. He was tried and convicted of war crimes and sentenced to death; De Gaulle commuted his sentence to life imprisonment because of Pétain’s age, which was eighty-nine. He died in prison in 1951.

Henry L. Stimson

Secretary of state Henry L. Stimson, was a former U.S. attorney who brought great political and economic experience to the government. He served as secretary of war under President William Howard Taft and helped organize the military expansion during World War I, even seeing combat time in France. Stimson then served as secretary of state under president Herbert Hoover. He retired to private life when Roosevelt was elected.

Stimson issued the famous Stimson Doctrine in response to Japan’s invasion of Manchuria. This doctrine was the official U.S. position against the Japanese invasion, which was a refusal to recognize the territorial claims of the aggressor.

In 1940 Stimson accepted FDR’s invitation to re-enter the cabinet and assumed his old post as secretary of war. In this capacity, Stimson built the American military up to an eventual force of 10 million. His leadership during the war was invaluable in maintaining an overwhelming demand for men and raw materials.

A strong advocate of containing Japanese aggression, he was a prime supporter of the design and eventual use of the atomic bomb. He also played a leading role in determining the postwar fate of Germany and its leaders. Stimson retired from the cabinet not long after the war ended and died just four years later.

Anne Frank

Many fifteen-year-olds keep a diary, but none has influenced the world quite like Anne Frank’s. Through her poignant words, the world learned what it was like to be an adolescent Jewish girl living in fear of Nazi persecution.

Anne was born in Germany in 1929, and her family moved to Amsterdam in 1933. The Germans invaded the Netherlands in 1940, and the roundup of Dutch Jews began shortly thereafter. At great risk to themselves, Christian friends saved Anne, her family, and four others by housing them in a hidden area of what had been a warehouse. There, the group lived for two years in constant fear of discovery by the Nazis, who were sending Dutch Jews to concentration camps by the thousands.

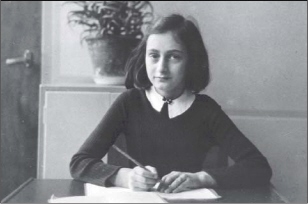

Figure 9-2 Anne Frank writes at her desk.

Getty Images/Anne Frank Fonds— Basel/Anne Frank House/Contributora

During her time in hiding, Anne kept a detailed diary describing her life, hopes, dreams, and fears. Foremost was the agonizing question of how people could treat others so brutally—a question that remains unanswered today. She started the diary on June 12, 1942; her final entry was dated August 1, 1944.

On August 4, 1944, Gestapo agents, tipped off by a Dutch informer, burst into the warehouse and arrested all who were living inside. The agents ransacked the room but considered Anne’s precious diary inconsequential and threw it in a corner. Anne and her family were separated and sent to concentration camps. Her mother died at Auschwitz, while Anne and her sister, Margot, eventually died at Bergen-Belsen. (This camp was liberated by the British in April 1945, just a month after Anne died.)

A new edition of Anne Frank’s diary was published in 2001 with five previously omitted pages describing her parents’ loveless marriage and Anne’s troubled relationship with her mother.

At the end of the war, the only family member still alive was Anne’s father, Otto. He returned to the family’s secret hideaway in Amsterdam and found Anne’s diary in the corner where it had been tossed by the Gestapo agents. The diary, published under the title Diary of a Young Girl, was an international bestseller and became required reading in many U.S. schools. It was also adapted for theater and a motion picture.

Oskar Schindler

Until director Steven Spielberg brought his story to the big screen in the 1993 movie Schindler’s List, most people had never heard of Oskar Schindler. Today, Schindler is renowned worldwide for his efforts to protect Jews from German persecution.

Schindler, a Catholic, was born in what is now the Czech Republic in 1908. He held a number of jobs before becoming a sales manager for an electrical products manufacturing company. In the late 1930s, the German government asked Schindler to spy against Poland during his frequent business trips there.

After the German conquest of Poland, Schindler moved to Krakow to run an enamelware factory that primarily employed low-paid Jewish workers. Jews flocked to his factory begging for work because Schindler could use his business connections in the German government to prevent his laborers from being taken to concentration camps. Schindler was both self-serving and compassionate in his efforts to protect his Jewish workers—he was irritated by the fact that Nazi brutality adversely affected his factories’ production, but he was also morally repulsed by Germany’s anti-Jewish campaign.

In 1943, the Nazis decided to send all the Jews living in the Krakow ghetto to a concentration camp at nearby Plaszow. Schindler managed to save a great many who would otherwise have been doomed by building a camp on his factory grounds and convincing German officials to let his employees stay there.

In 1961, Israel commemorated Schindler’s efforts with a memorial that was unveiled on his fifty-third birthday. Germany also rewarded Schindler’s efforts with the Cross of Merit in 1966 and a state pension in 1968. Oskar Schindler died in 1974. His story first became widely known as a result of Thomas Keneally’s 1982 book Schindler’s Ark.

A year later, as Soviet troops approached Krakow, the German government ordered all Jews in both the Plaszow concentration camp and Schindler’s company camp sent to Auschwitz for extermination. Schindler used a combination of personal charm, bullying, and bribes to convince the Nazis to let him move his factory (and his workers) to Czechoslovakia instead. He created a registry—the now-famous Schindler’s List—of more than 1,000 employees he wanted to accompany him to his new factory. Had Schindler not done so, those individuals almost certainly would have been killed. Schindler and his workers remained in Czechoslovakia until the end of the war.