Bombers

The development of high-speed offensive bombers really took off in the 1930s. All sides of the war made extensive use of bombers in terrifying air assaults.

Allied Bombers

One of the most influential bombers to come out of that era was the B-17 Flying Fortress, which was widely used by the Allies in both the European and Pacific theaters throughout the war. The B-17 was popular because it had a formidable defensive gun armament (hence the name Flying Fortress) and could also sustain considerable damage and still make it home.

Fig 11-1 The Avengers flying in formation, September 1942.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-417475)

Equally important in the overall war effort was the B-24 Liberator, a heavy bomber produced in greater numbers than any other U.S. military aircraft. The B-24 was used primarily as a long-range bomber and saw service as such in Europe, the Pacific, and North Africa. However, it was also used as an antisubmarine plane, for reconnaissance, and to haul cargo.

The Memphis Belle was the first U.S. bomber to successfully complete twenty-five missions over Europe, and as a result it became one of the best-known aircraft of the war. The Memphis Belle, a B-17 Flying Fortress, was named by Captain Robert Morgan for Margaret Polk of Memphis, Tennessee. In addition to their bombing runs, the crew shot down eight German fighters.

The B-29 Superfortress was the next step in the evolution of American-designed heavy bombers and was by far the most advanced bomber to see action in the war. The B-29 was used extensively in bombing raids against Japanese industrial and urban targets during the latter months of the war. In addition, the B-29 was the first U.S. bomber with a radar bombing system, which replaced the popular Norden bombsight for precision bombing.

The B-32 Dominator was created just in case the B-29 failed to live up to expectations. Also a heavy bomber, it saw limited action (only fifteen actually flew in combat in the Pacific before the end of the war) because the B-29 proved to be so reliable and effective. However, the B-32 was a very solid plane with tremendous defensive capabilities. In one incident in August 1945, two B-32s on a photo mission over Tokyo were attacked by fourteen Japanese fighters. One Dominator was damaged in the ensuing battle, but both managed to return safely to their base in Okinawa.

Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima, was a B-29.

The B-36 Peacemaker was a long-distance bomber designed to attack European targets from bases in North America. The plane was also considered for duty in the Pacific as a result of problems with the B-29 and B-32. However, the first B-36 didn’t roll off the assembly line until August 1946— a year after the end of the war and nearly five years after the prototype was first ordered.

Even more distinctive in concept was the B-35 Flying Wing, a long-range bomber that, as its name implies, looked like a flying wing. The plane was conceived of as a transatlantic bomber, and the order for a prototype was received by Northrop in 1941. The first B-35s took to the air in June 1946, too late to participate in the war.

Who painted the noses of fighter planes during the war?

The job usually went to the crewman with the most talent. Lacking that, crews would often offer to pay others to do the job, though usually it was done for free. The farther from headquarters a crew was based, the more daring it made its nose art. Air crews were encouraged to keep their nose art inoffensive when close to home.

Medium-range Allied bombers included the B-25 Mitchell (which was flown by Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle and his raiders during their famous attack on Tokyo in April 1942) and the B-26 Marauder (which Allied pilots disliked because of its high accident rate and difficulty in bailing out).

Axis Bombers

Germany and Japan also had very effective medium- and long-range bombers, as well as other craft. In the German Luftwaffe, the Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber was most commonly used for air support and tactical bombing. Thousands of the planes were produced over the course of the war, and the Ju 87 participated in all early blitzkrieg attacks, as well as almost every major battle in which air support was needed. The plane carried bombs under the wings and fuselage and was unique in its use of an autopilot if the pilot blacked out during a dive. The use of sirens on the undercarriage made its natural scream even more terrifying to enemy troops.

Germany, like the Allies, experimented with a number of intriguing war plane prototypes. The Ju 390, a transatlantic bomber, was originally conceived of for strategic bombing missions against the United States from bases in Europe. In January 1944, the Ju 390 was tested with a mission that took it across the Atlantic to within twelve miles of New York City and back again. The plane was never mass-produced and did not see action during the war.

The Ju 88 was one of Germany’s most commonly used medium-range bombers. In fact, the plane was so popular because of its versatility that more Ju 88s were produced than any other German bomber. Like the Ju 87, it participated in nearly all German aerial campaigns and inflicted tremendous damage on enemy targets.

The most effective dive-bomber used by the Japanese was the D3A Val, which inflicted tremendous damage during the attack on Pearl Harbor. A workhorse of the Japanese air force, the plane saw action throughout the Pacific and Indian Oceans. By mid-1944, however, the Val had largely been replaced by the A6M Zero fighter-bomber and to a lesser degree by the D4Y Suisei (Comet) bomber (code-named “Judy” by the Allies). The D4Y Suisei was most commonly used for kamikaze attacks against Allied ships.

Torpedo Bombers

One of the weapons most feared by seamen during wartime was the torpedo bomber, which was used by both sides against surface ships. The primary U.S. torpedo bomber at the start of the war was the TBD Devastator. Though capable of inflicting tremendous damage on enemy ships, the Devastator was slow and extremely vulnerable to attack by other planes. Devastators helped sink the Japanese light carrier Shoho at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 but proved useless during the Battle of Midway the following month; all three flights of U.S. Devastators were destroyed by Japanese defenses without hitting a single Japanese carrier. However, aerial torpedoes helped sink the Japanese battleships Yamato and Musashi.

Captain Robert Morgan, the pilot of the Memphis Belle, also flew the first B-29 Superfortress to bomb Japan.

In May 1943 Allied aircraft started using the acoustic antisubmarine torpedo known as Fido, which homed in on the sound of a submarine’s propeller. Similar devices were used by German submarines against Allied surface ships. Torpedo bombers were used throughout the war, but dive-bombers eventually took over as the navy’s primary striking force.

Bombs

Thousands of aircraft bombs were dropped by both sides over the course of the war, devastating entire cities and killing hundreds of thousands of people. A wide variety of bombs were used by the U.S. Army Air Forces, including high-explosive, fragmentation, and incendiary warheads. Bombs were also developed for chemical and biological warfare, but they were not deployed during World War II.

U.S. high-explosive bombs ranged in size from 100 to 4,000 pounds, though the larger sizes were seldom used. (An experimental 42,000-pound high-explosive bomb was created by the Army Air Forces in 1945 but was never used in the war.) Fragmentation bombs—also known as antipersonnel bombs—came in 20-, 23-, and 30-pound sizes and were dropped on enemy ground troops.

Incendiary bombs, which used chemicals to start fires, were usually fifty pounds in size and were often dropped in clusters to create a fast-moving blaze. Sometimes demolition bombs were dropped first to blow off roofs so the incendiary bombs that followed would be more effective in destroying target buildings. According to bomb experts, incendiary bombs were far superior to explosives for wholesale destruction, and entire cities, such as Dresden, Germany, were burned to the ground as a result of their use.

Map 11-1 Air offensive in Western Europe as of September 6, 1943.

Map courtesy of the National Archives (RG 160, Vol. 2, No. 20)

Toward the end of the war, the Japanese sent incendiary bombs to the United States and Canada via balloon. Few reached their targets, and damage from the balloon bombs was minimal. The only casualties were Elsie Mitchell and her five children, who found a balloon bomb while fishing in Lake County, Oregon. The bomb detonated while they were examining it. The Mitchells were also the only casualties from enemy action on the U.S. mainland.

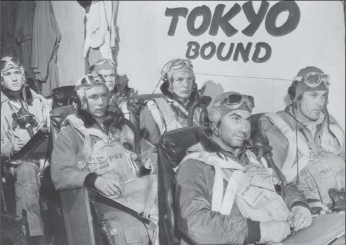

Fig 11-2 Pilots aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier receive last minute instructions before taking off to attack industrial and military installations in Tokyo.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (208-N-38374)

The British created a number of large bombs, including a 4,000-pounder that could level an entire city block. This “blockbuster” bomb was first used against the German port of Emden on April 1, 1941. The largest bombs used during the war were British-made 12,000- and 22,000-pound “earthquake” bombs known, respectively, as Tallboy and Grand Slam. These bombs were used against German submarine pens and other heavily fortified targets and proved quite effective. A Tallboy bomb was also used to sink the German battleship Tirpitz, which had survived blasts from smaller bombs.

Some large bombs were equipped with parachutes to slow their fall so aircraft could safely escape the blast area before they detonated.

The largest Axis bomb used was the German 5,511-pound SB 2500, which carried an explosive charge of more than 3,700 pounds. The bomb was effective, but few were dropped during the war. The most destructive Allied bombs, of course, were the atomic bombs used to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Fighter Planes

Bombers were not the only offensive planes used by Allied and Axis forces during World War II. Equally effective were fighter planes, which were used to defend bombers and attack other planes, ships at sea, and ground troops.

Fighters played an extremely important role in defending Great Britain during the Battle of Britain. Hermann Goering was confident his Luftwaffe would be able to make short work of the Royal Air Force, but the British Hurricane and Spitfire fighters quickly proved that Great Britain was not about to roll over. The planes were extremely successful in defending the British coast, and the RAF downed considerably more planes than it lost.

Fig 11-3 Pilots pleased over their victory during the Marshall Islands attack grin across the tale of an F6F Hellcat on board the USS Lexington, after shooting down seventeen out of twenty Japanese planes heading for Tarawa.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-470985)

The Hurricane became part of the RAF’s air arsenal in December 1937. The Spitfire followed in 1939 and quickly became one of the foremost Allied fighter planes of the war; it was even used during the Normandy invasion to direct gunfire from nearby warships.

The U.S. military was racially segregated during the war, with African-American servicemen serving in special units. The most famous was the Ninety-ninth Pursuit Squadron, the first African-American combat unit in the Army Air Forces. The unit was established in Tuskegee, Alabama. The so-called Tuskegee Airmen completed more than 500 missions in its first year of action. More than eighty members were decorated.

Fighter Plane Evolution

The United States also produced a wide variety of fighter planes during the war. The first fighter aircraft to see combat was the P-36, which was produced primarily for use by foreign air forces, though a few were flown by the U.S. Army at the start of the war. A variant of the P-36 was the Hawk 75, which was first flown in 1937. It, too, was primarily sold to other nations. (A handful of captured Hawk 75s were flown by the Germans after the fall of France.)

The P-47 Thunderbolt was the most widely flown American fighter of the war. In fact, in 1944 and 1945, the Thunderbolt was flown by more than 40 percent of all army air force fighter groups overseas. The plane was widely used in both Europe and the Pacific and was surpassed in performance only by the P-51 Mustang, which was considered the most reliable and effective land-based fighter of the war. Because of its long-distance and defensive capabilities, the Mustang allowed U.S. heavy bombers to fly over Europe during daylight rather than under the cloak of night.

Other effective American fighter planes included the P-38 Lightning, which had the longest range and greatest performance of any American fighter at the beginning of the war; the P-39 Airacobra; the P-40 Warhawk; the P-61 Black Widow, which was the first American plane developed specifically as a night fighter; and the P-80 Shooting Star, the first U.S. jet-propelled combat aircraft. Though the Shooting Star came out of development too late to see service in World War II, it was one of the first U.S. jet aircraft put into combat in the Korean War.

Probably the most feared Japanese fighter plane was the A6M Zero, which created havoc in the Pacific for the first two years of the war. Developed by Jiro Horikoshi, the Zero was the first plane to prove that a carrier-based aircraft could hold its own against land-based fighters. The Zero, which reached speeds of more than 300 miles per hour, was used in the attack on Pearl Harbor and in almost all Japanese naval air battles after that. It wasn’t until the introduction of the Navy’s F6F Hellcat in 1943 that an Allied fighter could defeat the Zero under all combat conditions.

The Dreaded Kamikaze

Allied naval personnel serving in the Pacific faced numerous hazards every day, but few were more dreaded than the Japanese naval suicide squads known as kamikaze.

The Japanese navy began organized suicide attacks against Allied forces on October 25, 1944, in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, though individual Japanese pilots had routinely aimed their planes at U.S. ships when their craft was damaged and they had no hope of returning safely to base.

The idea of organized crash-dive attacks was conceived of by Captain Motoharu Okamura, commander of the 341st Air Group, who felt such a program was the only way to prevent a U.S. advance on the Japanese mainland. “Provide me with 300 planes, and I will turn the tide of the war,” Okamura told Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi in June 1944.

The first Japanese Zero to fall into American hands was found in the Aleutian Islands, where it had crashed, killing its pilot. The plane was repaired by American technicians, who marveled at its unique design, and made its first flight with U.S. markings in October 1942.

The Japanese called the suicide squads “kamikaze” after the super-strong “divine winds” that were said to have destroyed Mongol fleets sailing to invade Japan in 1274 and 1281. The first kamikaze attacks in October 1944 were flown by twenty-four volunteers of the Japanese navy’s 201st Air Group on Leyte. Using A6M Zero fighters, the pilots focused their efforts on U.S. escort carriers that had engaged Japanese warships in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The first U.S. ship to be hit was the escort carrier St. Lo, which went up in flames after being struck by a Zero filled with explosives. The carrier went down in less than half an hour, taking 100 members of its crew with it. Two other escort carriers were damaged by kamikazes on October 25 but stayed afloat.

After that, the Japanese sent more than 1,250 aircraft on organized kamikaze attacks against U.S. forces during the battles for the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. The suicide squads sank 26 combat ships and damaged nearly 300 more. The largest U.S. ships sunk were 3 escort carriers, 13 destroyers, and a destroyer escort. Several U.S. aircraft carriers were damaged by suicide attacks, but none was sunk. An estimated 3,000 Allied personnel (primarily American and British) were killed in kamikaze attacks, and another 6,000 were wounded.

The Japanese also used small, piloted suicide submarines (actually torpedoes) called kaiten, which sank a U.S. tanker and a destroyer escort, and damaged several other ships. Overall, however, the kaiten program was a failure.

Gliders

Gliders were used by both sides to deliver troops and equipment to locations where traditional aircraft couldn’t go. Because they were unpowered, gliders were particularly good at delivering their cargo undetected behind enemy lines.

The Treaty of Versailles prevented Germany from having an air force, so German aviators formed glider clubs to retain their flight skills and train new pilots. From that came increased interest in gliders as military weapons. Large gliders were found to be superior to parachute landings in efficiently delivering large numbers of troops and equipment to a specific site.

One of the first significant German military gliders to be developed was the DFS 230, which could carry nine men. It was first test-flown in 1937 and proved to be quite useful. A glider commando force was formed in 1938, and production of the DFS 230 was greatly increased. By 1943, more than 1,500 of the craft had been made. During the German campaign of 1940 in France and the Low Countries, gliders were used to take Fort Eben Emael on the Belgian border. Gliders were also used during the German invasion of Crete in 1941, to bring supplies to besieged German troops in the Soviet Union, and to rescue Benito Mussolini in September 1944.

Larger and better gliders were soon created by the German air force, including the Gotha Go 242, which could carry 21 men, and the massive Messerschmitt Me 321 Gigant, which could carry 130 soldiers, though it was used primarily to transport cargo.

The U.S. Army Air Forces ignored the glider concept until Germany proved the planes’ usefulness in a number of important airborne assaults in 1940 and 1941. Military aviation experts began to explore glider design in February 1941, and two distinct designs were eventually mass-produced: the CG-4A, which could carry thirteen men, and the CG-13, which could carry thirty. More than 14,000 of these gliders were produced over the course of the war.

The Allies used gliders to deliver troops and equipment during several crucial campaigns, including the capture of Sicily in 1943, the Normandy invasion in June 1944, and the Rhine crossings in 1945. Gliders were used sparingly in the Pacific because of the distances between bases and their objectives, as well as a shortage of transport craft.

Britain, the Soviet Union, and Japan all used gliders to varying degrees over the course of the war. The Soviet Union even designed a glider-bomber known as the PB, though the craft never left the drawing board.

Guided Missiles and Rockets

Both the Allies and the Axis explored the use of guided missiles—unmanned craft controlled by radio signals from nearby aircraft—as offensive and defensive weapons, with mixed results.

In 1944, the U.S. Army Air Forces and Navy worked together to refine the use of worn-out bombers packed with explosives as a weapon against German submarine pens, oil refineries, and other targets. The results of the top secret project, known as Aphrodite, were less than spectacular, and the concept was not implemented during the war. The use of radio-controlled fighters packed with bombs or napalm was also explored in 1945, but the war ended before the project could reach the development stage.

Specialized guided missiles were also widely researched. One concept involved fitting bombs with wings or controllable fins. A variety of glide bombs were developed, and in May 1944, bombers flying out of England dropped more than 100 of these GB-1s on Cologne, Germany. However, the results were disappointing, and no more attacks were approved. Improved GB-type weapons were tested in Europe over the course of the war, though they, too, had little success.

The Army Air Forces had better luck with vertical bomb weapons. The VB-1 Azon was a 1,000-pound bomb with a radio-controlled tail that allowed for much greater accuracy. It was used successfully against German targets throughout Europe and the Mediterranean in 1944 and 1945, as well as against Japanese bridges in Burma.

German Advances

Germany conducted extensive research into guided missiles and had its greatest success with the V-1 rocket, commonly known as the buzz bomb because of its distinctive drone. The V-1 was the first guided missile to be launched in large numbers against an enemy, and it inflicted tremendous damage and huge casualties on Great Britain starting in June 1944. In fact, during an eighty-day period, a nonstop rain of V-1s damaged or destroyed nearly 1 million buildings, killed 6,184 Britons, and injured more than 17,980 others. The city of Antwerp was also targeted with V-1s.

The U.S. Army Air Forces created its own version of the V-1 rocket in August 1944, using parts from recovered V-1s as a guide. The American version was called the JB-2 and was successfully tested in October 1944. General H. H. Arnold, head of the air forces, ordered the weapon into mass production. However, the initial numbers were scaled back because the high demand was exhausting production capability. Germany and Japan both surrendered before the guided missiles were put into wide use.

Many of the V-1s launched against England were duds though, and a large number were thwarted by planes and barrage balloons. V-1 production and launch sites in Germany became primary targets of Allied bombing raids.

Allied ships were another common target of German guided missiles. The primary guided bomb was the Kramer X-1, which carried a 1,300-pound armor-piercing bomb. The Luftwaffe successfully sank the Italian battleship Roma with a single X-1 on September 9, 1943. Many other Allied warships were heavily damaged by X-1s.

The V-2 Missile

Germany led the way in rocket research during the war, with deadly results. One of its most impressive rocket missiles was the dreaded V-2, a forerunner of the contemporary intercontinental ballistic missile.

At 46 feet in height, the V-2 was an impressive missile. Fueled by a mixture of liquid oxygen and alcohol, it weighed 28,373 pounds at launch and carried a 2,145-pound explosive warhead. Variations included a winged model called a glider, a two-stage rocket that would have been able to hit the United States from Europe, and a model that could be launched from a submarine. However, none of these was developed in time to have much of an impact on the war.

The V-2 was developed by a team of German rocket scientists led by Dr. Werner von Braun. After the war, he and many of his associates were brought to the United States, where they were instrumental in establishing the U.S. ballistic missile and space programs. Other German scientists aided the Soviet Union.

The experiments that led to the development of the V-2 started in the 1930s. The first operational launches occurred on September 6, 1944, when two V-2s were fired at Paris from the Peenemünde rocket facility on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Two days later, two more V-2s were fired at England. Over the next several months, England was hit by hundreds more. More than 2,700 Britons were killed by the rockets, and more than 6,500 were injured. Antwerp and Brussels were also frequent V-2 targets.

Unlike successful efforts to down the V-1 buzz bomb, no countermeasures could be taken against the V-2 once it had been launched. Fired from hundreds of miles away, the missile reached a terminal velocity of nearly 4,000 miles per hour; a flight of 200 miles took just a few minutes from launch to impact.

Airships

The U.S. Navy relied heavily on blimps for a variety of functions during the war and was the only service branch among all the war participants to use lighter-than-air ships.

When war broke out, the United States had only 10 operational blimps; by the end of the conflict, 167 were in service, most of them K-type airships. The blimps’ primary function was to search for U-boats and lead aircraft and surface ships to them, and the airships were highly effective in that role. No Allied convoys accompanied by a blimp experienced serious damage from enemy ships. Blimps were also used for rescues at sea.

Blimps were often equipped with machine guns and other weapons, and sometimes they engaged enemy ships. Only one Allied blimp was ever shot down. The K-74 discovered a surfaced submarine on July 18, 1943, and attacked it with machine guns and depth charges. The sub responded with a barrage of antiaircraft fire, and the K-74 was struck multiple times, forcing it down in the ocean. Amazingly, all but one crewman survived. The German submarine U-134 escaped but was later sunk in the Bay of Biscay by an RAF bomber.

Blimps were filled with nonflammable helium and propelled by two reciprocating engines. The K-type blimps had a cruising radius of approximately 1,500 miles and a top speed of about 75 miles per hour.