Aircraft Carriers

Aircraft carriers were generally the largest ships in any nation’s fleet and replaced battleships as the primary support vessels of the U.S., British, and Japanese navies during the war because their bomber aircraft were more flexible and could reach more-distant targets than the big guns of any battleship.

Most U.S. aircraft carriers saw action in the Pacific. When war first broke out, the navy had seven aircraft carriers in operation. They were the primary target of the Japanese attack against Pearl Harbor, but all were out to sea when the Japanese struck. Aircraft carriers played decisive roles in several important battles in the Pacific, including the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway. Though massive and heavily protected, aircraft carriers were not invincible, and several U.S. carriers were destroyed in combat. The Lexington, for example, was sunk at Coral Sea, the Yorktown at Midway, and both the Wasp and the Hornet during the campaign to take Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands. At one point in 1942, the Enterprise was the only operational carrier in the Pacific Fleet, and it was limping as a result of enemy attack.

In the motion picture Jaws, fisherman Quint, played by Robert Shaw, admits that his hatred of sharks stems from watching many of his shipmates get eaten alive after the sinking of the cruiser Indianapolis on July 30, 1945. That scene, rewritten by Shaw, was later called one of the movie’s best by its director, Steven Spielberg.

New carriers began joining the fray in 1943. By the middle of 1945, thirteen 27,100-ton Essex-class and nine 13,000-ton Independence-class light carriers were in service. These ships, capable of carrying large numbers of aircraft, conducted much of the Allied offensive against the Japanese, whose own fleet of carriers had been heavily damaged in fighting.

From the Battle of Midway until the end of the war, only one U.S. light carrier was sunk by enemy fire: the Princeton, which was hit by Japanese bombs during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944.

Only two American aircraft carriers saw action in the Atlantic. The Wasp was briefly part of the British Home Fleet and made two voyages into the Mediterranean Sea in April 1942 to unleash fighter planes during the campaign to take Malta. And the Ranger—kept out of the Pacific because of its slow speed and lack of torpedo planes—also aided the British in the Atlantic, particularly during the invasion of North Africa in 1942.

Figure 12-1 USS Iowa firing its 16-inch guns during a drill in the Pacific, circa 1944.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-59493)

The German navy did not have any aircraft carriers, though it did have some formidable battleships, including the 41,700-ton Bismarck and the 42,900-ton Tirpitz.

Battleships

The U.S. Navy had seventeen battleships in service when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Fifteen of them had been put into commission from 1912 to 1923; the other two—the North Carolina and the Washington—were more modern, having joined the fleet in early 1941.

When the Japanese attacked, nine of the older ships were in the Pacific Fleet. Eight were stationed at Pearl Harbor, and two of them (the Arizona and the Oklahoma) were destroyed in the attack. Five others were heavily damaged but were quickly repaired and put back into action. At the time of the Japanese attack, six of the older battleships and the two newest were in the Atlantic.

Over the course of the war, eight additional battleships were delivered to the fleet: four ships of the Iowa class and four of the South Dakota class. All of the modern battleships were equipped with nine 16-inch guns and a variety of smaller weapons. The four ships in the Iowa class were the largest and most heavily armed battleships on the seas with the exception of the Japanese Yamato and Musashi, both of which were eventually sunk by U.S. carrier aircraft. A larger class of battleship, to be known as the Montana class, was considered, but the program was canceled in 1943.

Figure 12-2 The crew of the U.S.

Coast Guard Cutter Spencer watch charges explode while searching for German U-boats.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (26-G-1517)

The primary role of U.S. battleships was to provide antiaircraft defense for carrier task forces and shore bombardment to reduce enemy resistance before amphibious landings. However, there were two major battleship-to-battleship fights off Guadalcanal in 1942. In one of them, the Washington sank a Japanese battle cruiser while suffering no damage itself, though another U.S. battleship was heavily damaged by Japanese cruisers and destroyers.

In addition, six U.S. battleships—four of them survivors of the Pearl Harbor attack—engaged Japanese ships in an impressive night battle during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. Two Japanese battleships were sunk during the fighting.

No U.S. battleships were sunk by enemy fire after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Destroyers

Destroyers were some of the most plentiful surface ships in the war and were used to great advantage by both the Allies and the Axis. Smaller and faster than battleships, destroyers were used primarily to intercept enemy destroyers and other warships and disable them with torpedoes. If necessary, crippled enemy ships were then finished off by larger battleships or cruisers.

The U.S. Navy had 171 destroyers in service when America entered the war. Of that number, 71 had been built during or immediately after World War I and the rest put into commission after 1934. (Several older destroyers were also used as light minelayers, minesweepers, and transports.) All U.S. destroyers had banks of torpedo tubes, and the newer ships were also equipped with 5-inch guns to defend against—and attack—planes and surface ships. American destroyers also had sonar for tracking other ships, depth charges for use against submarines, and machine guns.

The first destroyer action of the war involved the Ward, which sank a Japanese midget submarine as it tried to enter Pearl Harbor just minutes before the Japanese air attack. (Three destroyers were heavily damaged during the attack but were completely rebuilt and placed back in service.) After that, destroyers saw action in all theaters of combat. Like battleships, they were also used to soften up enemy coastal defenses before amphibious landings.

Two U.S. destroyers lost during a typhoon off Luzon provided the setting for Herman Wouk’s novel The Caine Mutiny, which was turned into a popular motion picture starring Humphrey Bogart.

Production of destroyers escalated dramatically over the course of the war, with American shipyards delivering nearly 400 of the versatile ships. A total of 71 U.S. destroyers were lost during the war—more than any other type of warship. Most were sunk by enemy planes and ships (including 9 by Japanese kamikazes), though 3 U.S. destroyers went down as a result of accidental collisions, and 2 were lost during a typhoon off Luzon.

Submarines

The submarine was one of the most effective offensive naval craft of the war and was used to great advantage by the United States against the Japanese in the Pacific and by the Germans against Allied convoys in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

At the start of the war, the United States had 114 submarines. In the Pacific, 22 fleet boats operated out of Pearl Harbor, and 23 fleet boats and 6 older S-boats were based at Manila Bay in the Philippines. Sixty-three additional submarines of various classes were based along both U.S. coasts.

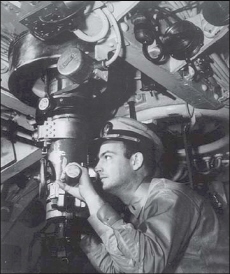

Figure 12-3 An American submarine officer scanning the surface.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (80-G-11258)

The fleet boats were large, long-range submarines built in the decade before the war to protect surface ships. They were more than 300 feet long and equipped with ten 21-inch torpedo tubes and a stock of up to twenty-four torpedoes. They were also armed with a single 76-mm deck gun and several machine guns. The smaller S-boats were not as spacious as the larger subs, could not dive as deep, and were armed with only four torpedo tubes.

At the onset of the war in December 1941, U.S. submarines in the Pacific were ordered to search for and destroy Japanese merchant ships rather than support the surface fleet, as originally intended. But the mission was impeded by recurring problems with faulty torpedoes, a situation that was not completely remedied until 1943.

The first successful U.S. submarine attack occurred just a week after Pearl Harbor, when the Swordfish sank the Japanese merchant ship Atsutasan Maru off Indochina. On January 27, 1942, the Gudgeon became the first U.S. submarine to sink a Japanese warship when it successfully torpedoed the submarine I-173. The attack was one of many based on information derived from decoded Japanese naval communiqués. Over the course of the war in the Pacific, U.S. subs sank nearly 1,300 Japanese merchant vessels, 4 fleet and 4 escort carriers, a battleship, 12 cruisers, 42 destroyers, 22 undersea craft, and 2 Soviet merchant ships mistaken for Japanese vessels.

Smaller older American submarines patrolled the east coast of the United States and the Panama Canal Zone during the early days of the war, though they saw little action. Then, in the summer of 1942, Roosevelt responded to a request by Winston Churchill and ordered six fleet-type submarines to the Atlantic, to be based in Scotland. The subs participated in the invasion of North Africa, but poor weather and confused recognition signals resulted in the Gunnel and the Shad being attacked by friendly fire.

U.S. submarines fired an estimated 14,750 torpedoes at 3,184 enemy ships over the course of the war. More than 1,300 enemy vessels were sunk, and submarines received “probable credit” for another 78 ships.

German submarines—called U-boats—patrolled the Atlantic during the early months of the war, sinking a great many Allied supply ships and dramatically affecting the European war effort. They played an integral role in the Battle of the Atlantic and were slowed only after the development of radar and increased use of antisubmarine ships and planes.

The first U-boats were launched in 1935 in direct violation of the Treaty of Versailles. When the war began, Germany had fifty-seven U-boats in commission, twenty-six of them large enough for ocean patrol. Their numbers increased quickly, and the German U-boat soon became the scourge of the Atlantic, which it easily accessed after the fall of Norway and France in 1940. By the end of 1942, nearly a hundred U-boats were in operation, with more to follow.

Germany and the Allies played a continual game of catch-up when it came to the U-boat, with every new submarine advance being met with a countermeasure. Germany also designed larger, better armed, and better equipped submarines such as the Type XXL, but few were produced, and they had little influence over the course of the war.

Other Sea Weapons

Warships weren’t the only sea weapons to be used during the war. A wide variety of other weapons were also employed including:

• Torpedoes. Launched from submarines, destroyers, or aircraft, torpedoes were effective against both surface and undersea ships.

• Numerous sizes and designs were used throughout the war, with improvements occurring regularly. Japanese torpedoes were far superior to Allied torpedoes, with the Japanese Type 93 being the largest torpedo used in the war.

• Mines. Several hundred thousand naval mines were placed over the course of the war. Four basic types of mines were used: acoustic mines, which were detonated by the sound of a ship’s engine or propeller; contact mines, which exploded when struck; magnetic mines, which detonated when disturbed by a steel-hulled ship; and pressure mines, which reacted to changes in water pressure caused by a passing ship. Some mines had multiple capabilities.

• Depth charges. Developed and first used during World War I, depth charges were surface ships’ primary method of defense against submarines. They typically consisted of a metal cylinder filled with explosives and fitted with a fuse that caused the canister to explode at a specific depth. Because surface ships often did not know exactly where or at what depth a submarine was, depth charges were often scattered in a fan pattern and set to go off at incremental depths. Depth charges were also dropped from submarine-hunting planes and blimps.

Liberty Ships

The workhorse of the combined Allied navies was the mass-produced “Liberty” cargo ship. More of them were made during the war than any other ship in history. Sturdy and reliable, they served in every theater of action.

The Liberty ship design was based on the old British “tramp” steamer, with modifications for wartime use. Each ship measured 441 feet long and could carry nearly 11,000 tons of cargo. Powered by steam engines, they had a maximum speed of 11 knots.

More than 2,700 Liberty ships were produced at nineteen American shipyards from 1941 to 1945. By December 1943, a complete Liberty ship could be built and delivered in twenty-seven days, with fourteen days for fitting out.