Germany Surrenders

The Allied victory over Germany—celebrated on V-E Day, or Victory in Europe Day, on May 8, 1945—was hard won, with political complications arising in the weeks and months leading up to Germany’s unconditional surrender.

The beginning of the end for Germany came on many fronts, though it could be argued that it started with the fall of Benito Mussolini in July 1943 and Italy’s surrender and withdrawal from the war in the following months. At first, Hitler showed little concern over the developments in Italy, believing that everything could be fixed by pouring more troops into the country and treating it like another occupied nation. He had little reason to feel otherwise, since this plan had worked so well in the past. However, the fall of Italy was the first in a long line of dominoes that would ultimately cost Germany the war.

No one in the German High Command dared suggest to Hitler that the end was near. In his madness, Hitler remained convinced that the Third Reich would still triumph.

Another domino was the successful invasion of Normandy, which planted Allied troops in occupied Europe and gave them the foothold they would need to push German forces all the way back to Berlin. By the time the primary Allied leaders—Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin—met at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the writing was on the wall. A lot remained to be done, but Germany was doomed. The Allies knew it, and the German High Command knew it, too.

A New German Leader

In April 1945, several important events came together to ensure the defeat of Germany. The first was the linkup of U.S. and Soviet troops at Tor-gau on the Elbe in the very center of Germany. The second was the surrender of German forces in occupied Italy. The third, and most important, was the suicide of Adolf Hitler on April 30. With a single bullet, Nazi Germany had lost its guiding light.

With Hitler’s death, Karl Dönitz became president of Germany and commander in chief of its armed forces. Hitler had instructed Dönitz to continue the war, but for all intents and purposes, it was already lost. Two months earlier, Heinrich Himmler had initiated talks with Count Folke Bernadotte, representing the Red Cross, on the release of some Scandinavian prisoners being held in concentration camps. These discussions quickly turned to the issue of Germany’s surrender.

Himmler wasn’t the first German official to send out feelers regarding an end to the war. Also in February, Karl Wolfe, the German military governor of Italy, contacted associates of Allen Dulles, the representative in Sweden of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, to discuss the surrender of German troops in northern Italy. Wolfe and Dulles met face-to-face the following March, when Dulles stated emphatically that unconditional surrender was the only term the Allies would accept. Wolfe reluctantly agreed, and secret plans were set in motion to work out the details. On April 29, the day before Hitler killed himself, the German Southwest Command surrendered all forces in Italy to a combination of American, British, and Soviet officers.

Next to lay down arms was the German state of Lower Saxony, which on May 4 surrendered to British field marshal Bernard Montgomery, acting on behalf of Dwight Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. The surrender agreement included German infantry and naval forces in Denmark, the Netherlands, and northwest Germany.

Germany Seeks Terms for Surrender

Dönitz knew the end was at hand. On May 6, he instructed Alfred Jodl, chief of the operations staff in the High Command of the Armed Forces, to negotiate an armistice with Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Dönitz hoped to work out a separate peace with Eisenhower without having to also surrender to the Red Army, which Dönitz rightly feared was preparing to enact a horrible vengeance against Germany. However, Eisenhower would have none of it and refused everything except an unconditional surrender that met all the Allied requirements set forth earlier.

Dönitz had to agree. On May 7, around 2:40 A.M., Jodl and two other German officers met with Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith, SHAEF chief of staff, and other military representatives from the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union in the SHAEF war room in the Professional and Technical School at Reims in northeastern France. The Germans and the Allies—with the exception of the Soviet Union—signed a surrender document; Eisenhower was not present because he refused to meet with German military officials until they had formally surrendered.

That document was not the formal surrender agreement, however. The official document, supervised by Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin, had been under revision since July 1944. Prepared by the European Advisory Commission (EAC), it was to spell out all the details of an unconditional surrender and offer possible solutions to the inevitable economic and political problems that were sure to follow.

The surrender didn’t officially take effect until 11:01 P.M. on May 8. The extension was given to allow as many German troops as possible to surrender to American forces rather than to the Red Army, which was out to exact revenge. Soviet officials demanded that a second ceremonial signing take place on May 9 because the Soviet observer at the first signing was too low in rank to sign on behalf of the nation.

Unfortunately, political difficulties prevented the Allies from presenting the EAC document at that time. France had not been included in the creation of the 1944 draft, and the word dismemberment, which had been added at the Yalta Conference to underscore the division of Germany, was not included. A revised draft was quickly written, but Eisenhower decided that the military surrender document, which officially ended hostilities, was sufficient for the moment and that all other problems could be worked out later.

The Axis Lays Down Its Arms

The first order of business was the question of how the Germans were to surrender. A second document addressed this issue with specific instructions on how, where, and when German forces were to lay down their arms. The document also stipulated that Germany was to immediately surrender all naval forces and provide maps of all minefields in European waters.

The Dönitz government remained in power for just over two more weeks. Dönitz, Jodl, and many other German officials were then taken into custody to be tried for war crimes at Nuremberg. Dönitz received a ten-year prison sentence for his role in the war. Jodl, who remained faithful to Hitler even during his trial, was hanged. However, a West German de-Nazification court concluded in 1953 that as a soldier, Jodl had not broken any international laws and posthumously cleared him of earlier charges.

Japan Surrenders

By mid-1944, the Japanese war machine was crumbling at a frightening rate, and a growing number of Japanese officials were in favor of ending hostilities. However, it would ultimately take the devastation of two atomic bombs to force Japan to capitulate.

Figure 14-1 A Navy chaplain holds Mass for marines in Saipan, June 1944.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (127-N-82262)

Japan, which had enjoyed a number of impressive military victories early in the war, was a dying giant by 1944. Its navy devastated by Allied forces and its exhausted army growing weaker by the day, Japan stood by in relative helplessness as American forces took Saipan in June 1944 and escalated the firebombing of the Japanese mainland using B-29 Superfortresses. Unable to defend against this brutal onslaught, many more Japanese officials began to seriously consider the need to bring the war to a close.

In the spring of 1945, Japanese government officials began a covert effort to initiate peace talks by contacting Sweden, the Soviet Union, and associates of Allen Dulles at the Office of Strategic Services in Sweden. U.S. intelligence, having broken the Japanese codes, knew all of this and fed the news to Washington.

The small but growing peace bloc within the Japanese government then turned to the Potsdam Declaration, which it felt offered some insight into the issue of Japanese surrender. According to these officials’ interpretation of the document, the unconditional surrender decree applied only to the military—not to the nation itself. This was good news.

Every member of the Japanese cabinet except for two hard-line generals favored a quick surrender, primarily to save their nation from U.S. bombers, which were slowly destroying Japan. While trying to persuade the dissenting generals that surrender was Japan’s only option, and to prepare the nation for the news, the government issued a statement saying that an offer of peace had been made but that the cabinet had decided to withhold comment. When the radio announcement was received by U.S. intelligence officials, they interpreted it to mean that the Japanese cabinet was ignoring a peace offer and intended to go on fighting. In early August, a frustrated Harry Truman authorized the use of the atomic bomb in an effort to force Japan to surrender.

The Atom Bomb

The atomic bomb is the most devastating weapon ever used in warfare. It was used twice against Japan near the end of World War II, but the threat of further use drove the Cold War and continues to threaten peace in the world today.

The bomb was the product of an American group of scientists under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who worked on a top-secret mission known as the Manhattan Project. Working in the isolation of the American Southwest, the scientists, lead by J. Robert Oppenheimer, built on the knowledge of and suggestions by famed physicist Albert Einstein and succeeded in splitting the atom.

Previous to the start of the Manhattan Project, a group of American scientists gathered at two historic conferences, one in Chicago and one in Berkeley, California. The top practical and theoretical physics minds in the land were at these conferences, and their discussions focused almost entirely on creating a superweapon. Among those speaking at the Berkeley conference was Hungarian physicist Edward Teller, who would play a major role in the discoveries that begat the bomb.

During 1942, when Japanese occupations were at their highest, the Manhattan Project achieved the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Subsequent developments built on that success, and by 1944, the atom-splitting operations were in full force. The first nuclear explosion took place on July 16, 1945, in the famed “Trinity” test near Alamogordo, New Mexico. That success led to the two bombs that devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

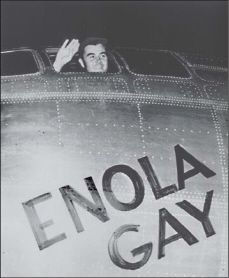

At 2:45 A.M. on the morning of August 6, 1945, Colonel Paul Tibbets, commanding officer of the 509th Composite Group, and his crew took off from Tinian Island in a B-29 Superfortress called the Enola Gay. In the plane’s belly rested the most destructive weapon created up to that time, a 9,000-pound atomic bomb nicknamed Little Boy.

Earlier that night, the residents of the Japanese port city of Hiroshima had gone through an air raid drill—something they had been notified of several days earlier. The first alarm went off shortly after midnight, and the all-clear sounded at 2:10 A.M. A yellow warning was sounded at 7:09 A.M., and the all-clear at 7:31 A.M. Approximately forty-five minutes later, the Enola Gay flew over the city. Most people thought the plane was part of the air raid drill—until a blast as bright as the sun incinerated the metropolis in the space of a heartbeat.

Unthinkable Destruction

The devastation wreaked by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima was unequaled in its time. Never before in human history had a weapon of such destructive force been unleashed on a population. The bomb was dropped from a height of 31,600 feet and exploded at about 1,900 feet— directly above Shima Hospital, near the heart of the city. Almost everything within a one-mile radius of the explosion’s center spontaneously combusted. Buildings disintegrated. The surface of granite stones melted under the intense heat. People vaporized, often leaving ghostly images imprinted on stone walls and sidewalks.

Figure 14-2 Colonel Paul Tibbets in the Enola Gay.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (208-LU-13H-5)

Those just outside the center of the blast also experienced atomic hell. Many people had their clothes blasted from their bodies. Hair was singed off, limbs ripped and seared, eyeballs melted. Those who survived the initial blast suffered a slow death from radiation poisoning.

The exact number of people killed in the Hiroshima blast remains unknown. The official Japanese estimate is 71,379 killed in the initial explosion and another 70,000 dead from radiation poisoning. A total of 70,000 buildings were destroyed or heavily damaged. Medical help was slow to reach those who so desperately needed it because more than 90 percent of Hiroshima’s doctors, nurses, and other medical personnel had been killed. Survivors overwhelmed hospitals in nearby cities.

News of the Hiroshima blast stunned the world—none more so than the Japanese, many of whom were joyously looking forward to a permanent peace. As the nation and its government reeled from what had occurred, the United States, fearing that Japan was still considering the continuation of hostilities, dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki three days later.

The Second A-Bomb

The second bomb, nicknamed Fat Man, was different from the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in that it used plutonium instead of uranium as its fissionable material. The bomb’s incredibly complex design had been tested in an explosion near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945.

The many components of Fat Man were flown from the atomic laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, to Tinian, where it was assembled and loaded on a B-29 nicknamed Bockscar, after its commander, Frederick Bock. On that particular mission, however, the plane was piloted by Major Charles Sweeney.

The second atomic bomb mission was extremely hazardous for the flight crew. Fat Man had to be assembled before being placed in the plane and was fully armed when the crew took off. Should the plane crash, a conventional explosion would disperse radioactive material over a frighteningly large area or, in the worst case, there would be a full nuclear explosion.

The Bockscar’s primary target was Kokura, the site of a major Japanese munitions dump. However, cloud cover blocked visibility, and after three passes the plane flew on to its secondary target, the port city of Nagasaki, a large shipbuilding center that also manufactured naval ordnance. It was a risky target because the Bockscar had only enough fuel for one pass, then a hasty return to Okinawa. Should the plane have to make more than one pass, the crew would have to ditch in the Pacific and hope to be rescued.

Nagasaki, like Kokura, was covered with clouds when the plane approached, forcing bombardier F. L. Ashworth to approve a radar run rather than visual bombing, as originally ordered. However, the clouds broke just as the plane reached the heart of the city, and Ashworth was able to see his target. The bomb was released and exploded at 1,650 feet with a force equivalent to 22,000 tons of dynamite.

As with Hiroshima, the resulting devastation was tremendous. Nearly 44 percent of the city was instantly annihilated in the blast, and more than 25,600 people were killed, with another 45,000 dead from radiation poisoning by the end of the year.

Japan Falls

Japan was finished. Emperor Hirohito, fearing a coup by stalwart militarists, immediately ordered that an official answer be sent accepting surrender. On August 10, Japan notified the United States through diplomatic channels in Switzerland that it accepted an unconditional surrender, asking only that the emperor be retained as sovereign ruler. U.S. officials responded that the rule of the emperor and the Japanese government were subject to the supreme commander of the Allied powers.

As the Japanese cabinet furiously debated the situation, the military struggled to keep the war going. To prevent such a move, Emperor Hirohito secretly recorded an announcement of surrender, which was broadcast over Radio Tokyo on the morning of August 15. In the address, the emperor said:

“We have ordered our government to communicate to the governments of the United States, Great Britain, China, and the Soviet Union that our empire accepts the provisions of their Joint Declaration.”

President Truman announced Japan’s official surrender at 7:00 P.M. on August 14, U.S. time. Allied occupation forces began landing on Japan’s shores just two weeks later, led by General Douglas MacArthur.

On September 2, 1945, Allied representatives including MacArthur, as supreme commander of the Allied powers, and Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainright, who had been a POW since the fall of Bataan, met with representatives of the Japanese government aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay to sign the official surrender document. Over the following weeks, entrenched Japanese forces surrendered on a number of fronts, including the Philippines, China, and Korea.

World War II was over. All that remained was to put the world back together.