The Need for a Scapegoat

Anti-Semitism had been a cornerstone of the Nazi Party since it was founded under the name of the German Workers’ Party in 1919. At that time, it had fewer than twenty-five members, only six of whom were active in promoting its ideals via lectures and discussions. Hitler joined the party shortly after its inception and quickly took control. He modified its name to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party and began refining its radical rhetoric for a broader audience.

Hatred and fear-mongering were strong components from the outset. At the first mass meeting of the German Workers’ Party in February 1920, Hitler read the party program, which he had helped write. The program consisted of twenty-five points emphasizing the importance and strength of nationalism, condemning Communism, and promoting racism and anti-Semitism. A strong centralized government and total control of the individual were essential if the party’s doctrines were to work.

During that first mass meeting, Hitler, speaking on behalf of the party, stated: “For modern society, a colossus with feet of clay, we shall create an unprecedented centralization which will unite all powers in the hands of the government. We shall create a hierarchical constitution, which will mechanically govern all movements of individuals.”

As foreign as these concepts may sound to those who have grown up in a democracy like the United States, they were music to the ears of millions of Germans who were looking for someone to guide them out of their nation’s stagnation. They also liked the fact that the Nazis offered them a villain in the Jewish people, thus removing the blame for Germany’s burdens from their own shoulders.

Hitler and the Nazis promoted anti-Semitism at every opportunity, and the concept became a key component of their rapid rise to power. From 1929 to 1932, Germany’s economic depression grew increasingly worse, and the Nazis used this to the fullest advantage by almost always blaming the growing problems on Jews and others. By beating the drum of nationalism during these increasingly dark hours, the party’s ranks filled by the tens of thousands.

The popularity of the Nazi Party and its extreme ideals reached its first important plateau in July 1932 when the party received 13.7 million votes in the national elections and won 230 of the 670 seats in the German parliament. Hitler lost the presidency to Paul von Hindenburg, but that was only a minor setback. After months of political wrangling, including the dissolution of the German parliament twice, Hitler was finally appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933.

Legislated Genocide

Hitler and his followers immediately enacted legislation making the Nazi doctrines of racism and anti-Semitism the law of the land. The program was instituted in four phases: (1) the economic persecution of German Jews, (2) the passage and enforcement of legislation to remove Jews from the German public and social life, (3) the forced removal of Jews from their homes in Germany and conquered lands, and (4) the eradication of all Jews through systematic mass murder.

Economic Persecution

Hitler began the economic persecution of the Jewish people on April 1, 1933, by ordering a boycott of all Jewish businesses. Falling back on the Nazi trick of claiming to do God’s work, Hitler stated: “I believe that I act today in unison with the Almighty Creator’s intentions: By fighting the Jews, I do battle for the Lord.”

Just in case the German people weren’t up for a boycott, the edict was enforced by SA goons who stood in front of Jewish-owned stores and verbally and physically intimidated all who might try to do business with them. Almost immediately, Jewish businesses saw a devastating drop in trade, and many were financially ruined within weeks.

This was just the first step. A week after instigating the economic boycott, Hitler removed Jews from the civil service. Then, over the course of the following year, he systematically ordered all non-Aryans (meaning Jews and those who had at least one Jewish parent or grandparent) removed from positions in banks, the stock market, the law, medicine, and journalism. The result was a national “brain drain” as thousands of prominent Jews in science and academia fled the country before it was too late. Among them were Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud.

What was the Gestapo?

The Gestapo, an acronym for Geheime Staatspolizei (secret state police), was formed in 1933 as a replacement for the Prussian secret police. It operated throughout Germany and all occupied lands, ruthlessly eradicating all political opposition by whatever means necessary. Individuals viewed as dangerous or subversive by Gestapo officials faced a number of fates, including incarceration, torture, and assassination.

From 1933 to 1937, an estimated 130,000 Jews fled Nazi Germany and Austria. However, the world didn’t exactly put out a welcome mat for them. In one of the most notorious incidents of international anti-Semitism, 937 Jews sailed from Germany for Havana, Cuba, aboard the liner St. Louis on May 13, 1939. When the ship reached its destination, however, all but 22 of the passengers were denied entry. The United States also refused entry to the ship. Having nowhere else to go, it returned to Europe, where the passengers got off and scattered for whatever safe haven they could find. Many were not able to find it, however—an estimated 600 of them died in concentration camps over the course of the war.

In late 1935, two years after his rise to power, Hitler successfully coaxed the Reichstag into passing what became known as the Nuremberg Laws, after the Bavarian Nazi stronghold. These laws essentially stripped Jews of all rights within Germany. Blood laws, for example, stated that only persons of “German or related blood” could be citizens. Other laws made Jews the property of the state, prohibited marriage or sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews, and prevented Jews from hiring female servants under the age of forty-five.

With the Jewish people’s legal protection removed by the state, persecution increased. The Nazis seized numerous Jewish businesses and canceled legally binding business contracts simply by claiming that the owners had violated one of the many Nuremberg Laws. Jewish employees of businesses owned by non-Jews were let go en masse. Anti-Semitism became compulsory in German schools with the teaching of so-called racial science and mandatory membership in Hitler Youth for all children except those of Jewish descent. Before too long, Jewish children were barred from attending public schools.

The Night of Broken Glass

The Nazi campaign against the Jews reached a murderous plateau on November 9, 1938, with Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. Using the assassination of a German diplomat in Paris as an excuse, Nazi officials secretly orchestrated a one-night campaign of vicious retribution against German Jews that resulted in more than 200 synagogues being burned to the ground, 7,500 Jewish businesses destroyed, and more than 800 Jews killed or severely injured.

Kristallnacht laid the groundwork for the roundup and elimination of Jews. With that single act, they ceased to be seen as human beings in the eyes of many Germans and were relegated to the status of vermin in need of eradication.

In the terror that followed, more than 20,000 Jews were arrested and 10,000 were sent to the concentration camp at Buchenwald. From that night on, no German Jew was safe from state-sanctioned attack.

Jews in German-Occupied Lands

After methodically removing the majority of Jews from Germany, the Nazis turned their attention to the Jewish populations of the countries that came under German control during the early months of World War II.

The first was Poland, which fell to the German blitzkrieg in early September 1939. On September 21, Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Reich Central Security Office, chaired a meeting in Berlin to address the question of what he called “the Jewish problem in the occupied zone.” While hinting of a far more sinister future plan for the Jews, Heydrich emphasized the need to eliminate all Jews from western Poland and concentrate those who lived in large cities into small, self-contained areas, or ghettos.

The largest ghettos were in Warsaw and Lodz, though ghettos were established in other Polish cities as well. They were small and tightly packed, yet the Nazis insisted on adding still more people from surrounding areas until living conditions became unbearable. (Many Jews not herded into ghettos were sent to labor camps, where they were forced to work under inhuman conditions.) Entire families were forced to live in a single, cramped room. Jews received half the food rations of non-Jewish Poles, a caloric restriction so severe that starvation was inevitable. Forced to wear a Star of David on their arm for easy identification, they were taunted, tortured, and routinely killed by Nazi occupation forces for no reason other than their heritage. German soldiers delighted in such barbaric practices as forcing Polish Jews to collect and burn religious scrolls while dancing around the flames singing, “We rejoice that this shit is burning.” Many Jews refused to participate and were shot for their insolence.

What’s most astonishing, with the hindsight of history, is that the German people let all of this happen. Not everyone was as vehemently anti-Semitic as Hitler and his core group of supporters. While the average German man or woman may have privately echoed certain anti-Semitic sentiments with friends and family, most worked with and/or socialized with Jews. They had friends and neighbors who were Jewish and patronized stores and businesses owned by Jews. And yet, very few people stood up and publicly declared that what the Nazis were doing was morally wrong. (Most of those who did were religious leaders, not average citizens.) A mass public dissent might have halted the Nazi campaign against the Jews before it turned into a holocaust, but such a public outcry never occurred, either because the people didn’t care or because they were too scared and intimidated by the military to risk their own lives for the sake of others. The power and scope of the German government’s military and spy networks during this period in history are breathtaking. Neighbors were led to suspect neighbors, (a practice that kept right on going in East Germany after the war ended). Although many Germans risked their lives to aid Jewish friends and associates, the overwhelming majority simply turned their backs as their Jewish neighbors were led away to an almost certain death. Even though instances of violence against Jews were well known, the existence of death camps was not common knowledge. Had more people known about the “Final Solution,” a public outcry might have been forthcoming.

Between the invasion of Poland and the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, an estimated 30,000 Jews were shot dead by German forces or killed by the starvation and disease that was rampant within the many ghettos and forced labor camps. But the worst was yet to come.

The Final Solution

Hitler’s ultimate aim, in its simplest context, was the complete eradication of all Jews from Germany and occupied lands. This process was code-named Die Endlösung (the Final Solution).

The phrase was first used by Hermann Goering on July 31, 1941, shortly after the invasion of the Soviet Union. Goering instructed Reinhard Heydrich to create a plan “showing the measures for organization and action necessary to carrying out the final solution of the Jewish question” in German-occupied Europe. Heydrich later added other groups to the extermination order, including Gypsies.

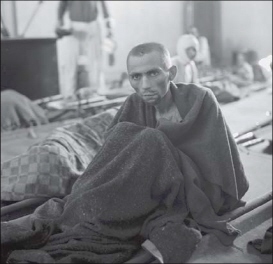

Figure 15-1 A starving inmate of Camp Gusen, Austria, May 1945.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (111-SC-264918)

In January 1942, Heydrich and his aide, Adolf Eichmann, chaired the Wannsee Conference, where one of the primary topics of discussion was “the final solution of the European Jewish question.” Also in attendance were representatives from the Occupied Eastern Territories, the ministries of Justice and the Interior and the Foreign Office, and various Nazi organizations.

In a horrifying example of raw Nazi barbarism, several German officials discussed the idea of eliminating 30,000 Gypsies by taking them by boat into the Mediterranean Sea and then bombing the boats. However, the idea was later abandoned.

The conference was held at the Reich Central Security Office in Wannsee, a suburb of Berlin. Eichmann acted as secretary, taking detailed notes of the strategies under discussion. At issue was how to deal with an estimated 11 million Jews in Germany and the occupied territories. According to Eichmann’s notes, Heydrich outlined a plan in which Jews capable of working would be sent in large labor gangs from other parts of Europe to conquered territory in the East. The survivors of the slave labor program represented “the strongest resistance” and were to be eliminated. It’s important to note that the word killed does not appear in Eichmann’s notes. Heydrich spoke in euphemisms, noting that Jews who survived forced labor “represented a natural selection” that must be “treated accordingly.” In short, those posing the greatest threat would have to be killed. During his trial in Israel in 1961, Eichmann said that he never saw a written order regarding the mass extermination of Jews. “All I know,” he said, “is that Heydrich told me, ‘The Führer ordered the physical extermination of the Jews.’”

The so-called Final Solution was carried out in two ways: via action squads that followed German troops into conquered lands with the specific mission of rounding up and executing Jews, and via death camps equipped with gas chambers and other methods of mass slaughter.

Unthinkable Atrocities

According to the Nuremberg International Tribunal on War Crimes, German action squads killed as many as 2 million men, women, and children in German-occupied territories over the course of the war. Most victims were rounded up, taken to a specific location outside the town or city, lined up in front of a large ditch, and quickly executed by firing squad. The bodies were then buried in mass graves. The murders committed by the action units remained a secret at first because there were usually no witnesses. However, word eventually leaked out of Germany that special death squads were murdering people on a massive scale.

The role of the death camps was to kill as many people as possible as quickly as possible—in other words, efficient genocide. Various methods were used over the course of the war, including firing squads and poisonous gases such as carbon monoxide and Zyklon-B.

Two extermination centers operated in concentration camps— Auschwitz-Birkenau and Lublin-Majdanek—under the auspices of the SS Central Office for Economy and Administration. Five others were in camps established by regional SS or police officials: Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka in eastern Poland; Kulmhof in western Poland; and Semlin outside Belgrade in Serbia.

The victims of Germany’s killing centers came from all over occupied Europe, though the first groups were deported from Polish ghettos. More than 300,000 were taken from the Warsaw ghetto, most of them women, children, and older men—individuals who could not work and thus could not benefit Germany. However, even those initially retained as laborers and workers were later scheduled for execution.

Death and Dishonor

Perhaps most horrifying is the fact that death did not end the degradation for many people murdered at Nazi extermination camps. Gold fillings were routinely removed with pliers from the mouths of corpses, and very often, skin was stripped from their backs, thighs, and buttocks, cured, and used to make lampshades, purses, and other articles. According to testimony at the Nuremberg war crimes trials, driving gloves made from human leather were particularly coveted among SS officers.

The heaviest deportations of Jews occurred in the summer and fall of 1942. The victims were transported by train and never told of their final destinations. However, news of the death camps eventually reached the ghettos, triggering organized resistance (much more so than in Germany itself). The greatest resistance effort occurred in the Warsaw ghetto, where in April 1943 nearly 65,000 Jews managed to hold off German police for three weeks.

The possessions of deported Jews did not go to waste. Everything the doomed people owned—from bank accounts to clothing and furniture— was acquired by the state for later distribution. Many Germans whose houses were destroyed by Allied bombing raids refurnished their new homes with furniture confiscated from deported Jews in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

Hitler’s desire to eliminate the Jews from Germany and all occupied lands created a political and bureaucratic nightmare for German officials. Some German-held countries, such as Vichy France, began deporting Jews even before being ordered to, but others were less cooperative. The Fascist government in Italy refused to deport Jews until the country was occupied by German forces in September 1943. Hungary also held out until Germany invaded in 1944. The government in Romania had no qualms about massacring Jews in occupied regions of the Soviet Union but refused to turn Romanian Jews over to the Germans. And in Denmark, tremendous efforts were made to save Danish Jews by covertly transporting them to neutral Sweden.

Concentration Camps

The concentration camps in which millions of Jews and others were systematically brutalized and killed remain one of the most horrifying images of World War II. When the camps were finally liberated in 1945, battle-hardened American, British, and Soviet troops often broke down in tears at the sight of the emaciated men and women and the conditions they had been forced to live under.

The term concentration camp was not new to World War II. It stemmed from internment centers created by the British to house Boer civilians during the Boer War of 1899–1902. German concentration camps were part of a system that also included slave-labor camps, whose prisoners worked at nearby factories, and death camps whose sole purpose was the efficient extermination of “undesirables.” The very first concentration camps were called “education centers” or “labor camps” by German propagandists, but their true purpose was the removal of Jews and others (such as Gypsies, the mentally and physically challenged, and so on) from German society.

Medical care at concentration camps was almost nonexistent for prisoners. As a result, countless men and women died from disease and poor nutrition. Women who became pregnant were forced to undergo abortions, though there were occasional exceptions. A special pregnancy unit was established at the Kaufering concentration camp in December 1944, during the waning months of the war. Seven women gave birth there, all of whom—including their babies—survived.

Figure 15-2 Jewish youths liberated from the concentration camp at Buchenwald on their way to Palestine, June 5, 1945.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (111-SC-207907)

The food given to concentration camp prisoners was usually of poor nutritional quality. Prisoners typically received about 1,800 calories or less per day yet were forced to perform hard labor requiring many times that amount. The result was a slow death by starvation.

The Allied soldiers who finally liberated Germany’s concentration camps were appalled by what they saw and outraged that such inhumanity could occur on such a wide scale. When General Dwight Eisenhower visited a work camp at Ohrdruf, near Buchenwald, he found rows of gallows in the cellar and more than 3,000 corpses throughout the camp, many of them bearing fresh head wounds—evidence that camp guards had systematically executed prisoners as Allied forces drew near. Eisenhower became so enraged when those living near the camp claimed to be ignorant of what went on there that he ordered every man, woman, and child from nearby towns marched through the camp at bayonet point. Afterward, he ordered the townspeople to bury the dead.

Secrets and Propaganda

The Nazis worked hard to keep their deadly secret from the world. Concentration camps were often referred to as “re-education camps,” and the camp at Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia was made to look like a model ghetto to impress outside visitors and calm new prisoners, who arrived by the trainload. Established in 1941, Theresienstadt housed a number of prominent Jews, including heroes of World War I, Danish Jews, and others who were actually forced to pay for what was euphemistically called a “transfer of residence.” The camp was ostensibly administered by a Jüdenrat, or Council of Jews, but, in fact, the Nazis held absolute power and intimidated council members into doing their bidding.

The Nazis forced the prisoners at the Theresienstadt concentration camp to make a ridiculous propaganda film titled Hitler Presents a Town to the Jews. However, the prisoners who acted in the film so obviously exaggerated the kindness of the Nazis that the film was never released. As retribution, many of the actors in the film were sent to their deaths at Auschwitz.

The Nazis often used Theresienstadt as a public relations tool, cleaning it up for the benefit of foreign dignitaries. Leaders touted the camp’s schools, concerts, and other artistic endeavors, but for the most part it was all a hoax. The people living at Theresienstadt could not leave, and thousands died there. Starting in January 1942, Theresienstadt was a stopover for prisoners being transferred to the death center at Auschwitz. More than 140,000 Jews were sent to Theresienstadt; fewer than 14,000 survived. Of the estimated 15,000 children who passed through its gates, fewer than 100 survived the war.

Concentration camps were guarded by SS members who were part of what became known as Death-Head detachments; members were identified by a special skull-and-crossbones insignia on their coats and caps. The guards were, for the most part, viciously cruel to prisoners, and spontaneous executions, often for something as minor as looking at a guard, were common. To get away with such an atrocity, all a guard had to do was claim that a prisoner had attacked him or was trying to escape. There were occasional acts of kindness among the less brutal among the guards, though these were extremely rare. Guards caught assisting prisoners were harshly punished.

Indeed, prisoners were routinely treated worse than animals. Many were forced to have identification numbers tattooed on their arms, and the standard-issue clothing was a vertically striped uniform with a triangular patch designating the prisoner’s category: red insignias for political prisoners, yellow for Jews, pink for homosexuals, black for “work-shy” prisoners, purple for Jehovah’s Witnesses, and green for criminals. Some prisoners overlapped in category and wore multiple patches.