Hard Times on the Home Soil

The prevailing emotion among most Americans in the days after the attack on Pearl Harbor was fear. The fact that Japanese bombers and fighters could inflict such tremendous damage on an American naval base suggested that they were capable of anything—including an attack on the American mainland. A minor panic ensued as municipalities from coast to coast enacted nighttime curfews and blackouts and piled sandbags in front of their most important buildings. Gun emplacements were constructed on top of buildings to defend against enemy planes, and scouts patrolled the beaches with binoculars, searching for planes and submarines. The enemy never showed up, but that didn’t prevent municipal leaders from exhorting the public to vigilance. “The war will come right to our cities,” said Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York. “Never underestimate the strength, the cruelty of the enemy.”

Many American servicemen fell in love while serving overseas. The result was an influx of war brides. In 1946, Operation War Bride brought 600 British women to the United States via passenger ship. That year, immigration officials report, 60,000 British women filed for emigration as brides or prospective brides. Another 12,000 applications were received from Dutch, French, Italian, and Australian women.

The Axis powers were a mysterious enemy to most Americans, so perhaps they can be forgiven for their panic. News was sparse during the early weeks of the war, and rumors and gossip ran wild. Anyone who appeared even slightly foreign was viewed with suspicion and distrust. American citizens of Japanese and German ancestry found themselves ostracized, if not actually attacked. Many businesspeople with foreign-sounding names took to plastering their store windows with American flags and signs reading “I Am an American!” to demonstrate their patriotism.

When no enemy planes came flying in over the oceans, panic and fear quickly gave way to a bizarre sense of wartime normalcy, though vigilance against enemy attack continued throughout the war. The Office of Civilian Defense, created by President Roosevelt in the spring of 1941, increased its efforts to encourage people of all ages to become involved in maintaining the nation’s defenses by volunteering in their communities.

Figure 17-1 Americans in line to buy rationed sugar.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (208-AA-322I-2)

The campaign worked: Americans volunteered by the millions for a wide variety of wartime defense programs. For example, over the course of the war, more than 1.5 million civilians volunteered as enemy plane spotters. They memorized the silhouettes of German and Japanese planes and spent their days and evenings scanning the skies with binoculars. No enemy planes were ever seen, but that never dampened the enthusiasm of the participants. Other volunteer programs included air raid wardens, security guards, and firefighters.

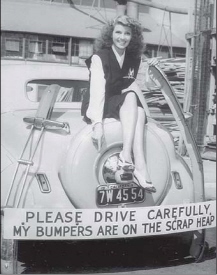

Rationing

Life in America during the war years was marked by sacrifice. The war effort demanded huge amounts of metal, paper, rubber, and other materials, and Americans were expected to donate as much of these substances as possible and live without until the war ended. Scrap drives were a common community activity, with high school groups going door to door seeking whatever materials homeowners could part with. Promotional campaigns featuring movie stars and other celebrities encouraged Americans to give until it hurt, then give some more. In one famous image, actress Rita Hay-worth sat atop her car, which bore a sign reading: “Please drive carefully. My bumpers are on the scrap heap.”

As the war effort increased, Americans learned to live with less and less. Shortages were common, and the rationing of essential materials like gasoline, rubber, and certain foods such as meat became part of everyday life for most Americans. Voluntary at first, rationing of some items became law as the war progressed.

Perhaps best remembered among those who lived in wartime America is gasoline rationing. Aimed at curbing the nonessential use of automobiles, the program required car owners to paste ration stamps on their windshields. An “A” stamp meant the car was for nonessential use, a “B” stamp meant it was needed for work, and a “C” stamp was for cars of essential drivers such as doctors. The type of stamp on a car’s windshield dictated how much gasoline could be bought for it each week. Additional rationing efforts encouraged the use of car pools and public transportation.

Figure 17-2 Actress Rita Hayworth promoting the national scrap metal drive.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (208-PU-91B-5)

A wide variety of common foods also fell into short supply as the government increased procurement for servicemen. In fact, nearly one-third of food items were rationed during the war years. Quality meat became increasingly difficult to find in civilian groceries, as did butter, sugar, coffee, and cheese. In one war-era animated cartoon, a picture of a steak smothered in onions appears briefly, then again at the end of the cartoon, so food-rationed Americans could gaze hungrily at what they had been missing for so long.

The Office of Price Administration was established in August 1941 to control and stabilize the prices of food and of goods and services and also to prevent the creation of a black market. Later, a presidential directive gave the OPA the authority to ration certain items. One of its first acts was to freeze the prices of nearly all everyday goods and most foods at March 1942 levels. Increases in rent were also severely restricted. The restrictions lasted until June 1946, when the prices of most items went up dramatically, sometimes as much as 25 percent over their wartime cost.

During the war, every family received ration books containing stamps to be given to grocers when buying certain items. Red stamps were used for meat (except for poultry, which was not rationed), butter, fats, cheese, canned milk, and canned fish. Green, brown, or blue stamps were used for canned vegetables, juices, baby food, and dried fruit. Shoppers could earn two extra red points for every pound of meat drippings and other fat they turned in as part of a national fat-collection campaign. Animal fats were used in a variety of wartime manufacturing processes, including the making of paint and munitions.

Music helped servicemen remember what they were fighting for. The music industry started producing patriotic melodies by the dozens shortly after the United States entered the conflict. Patriotic events almost always included a medley of songs honoring the armed forces. The most common were “The Caissons Go Rolling Along,” “Anchors Aweigh,” and “The Marine Hymn.”

Because of the food shortages, Americans were encouraged to plant what became known as victory gardens. In addition to placing food on the table of the average American, this freed farmers to provide still more food for America’s armed forces. Americans from all walks of life participated in the victory garden program, planting vegetables wherever space was available. In all, an estimated 20 million garden plots were created across the country.

War Bonds

Americans also helped finance the war by buying war bonds. More than $190 billion worth of bonds were purchased by private citizens over the course of the war. The program was heavily promoted with campaigns that involved movie stars, national celebrities, and even comic book heroes like Superman and Batman.

The first really patriotic song, ‘Remember Pearl Harbor,’ exhorted: “Let’s remember Pearl Harbor as we go to meet the foe. . . . Let’s remember Pearl Harbor as we did the Alamo.” Equally rousing was Frank Loesser’s “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” which was based on the legend that a chaplain had assisted gunners firing on Japanese planes.

Eight war bond drives were conducted from December 1942 to December 1945, and the response was tremendous. Two out of every three Americans, many using payroll deduction plans, bought Series E bonds, which were first issued in September 1943. Even children got into the act, pasting twenty-five-cent war bond stamps into a special book until it was full and they could redeem it for a $25 bond.

The interest rate for war bonds was 1.8 percent, compared with 4.25 percent for similar bonds issued during World War I. But most Americans didn’t mind because buying the bonds made them feel as if they were really helping the war effort, which they were. Small investors bought about $40 billion worth of bonds, with the rest being purchased by commercial banks, states, local governments, and other bodies.

Many families proudly displayed blue stars in their front windows to indicate that they had a family member serving in the military. The blue star was replaced with a gold star if the family member was killed in action.

The Role of Propaganda

Every war involves propaganda, and World War II saw plenty of it on both sides. It took many forms—posters, advertising, songs, comic books, comic strips, newsreel shorts, and even motion pictures—and was used to educate and influence both civilian populations and the men fighting on the front.

The word propaganda comes from the Italian Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Sacred Congregation for Propagating Faith), a papal organization that spread the Christian faith. The primary goal of propaganda as we know it today is to strengthen and enforce core beliefs and sway public opinion.

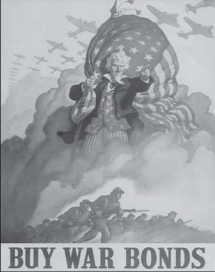

Figure 17-3 An American wartime poster.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (44-PA-531)

The Nazis used propaganda in two ways: to spread and preserve the basic doctrines of Nazism and to dehumanize “inferior” groups such as the Jews so that it would be easier for the German people to hate and exterminate them. Joseph Goebbels, chief of Nazi propaganda, was a master of the art form. He used every medium at his disposal to blanket Germany and the conquered lands with pro-Nazi propaganda. Goebbels found the radio to be particularly effective, and so almost every German family had at least one radio—specially constructed so that it was not able to receive anti-Nazi broadcasts from Great Britain and elsewhere.

The success of the Nazi propaganda machine was tremendous. Hitler was elevated to the status of national savior based solely on Goebbels’s tight control of the national press and his skill at turning political rallies into full-blown multimedia events.

The Allies also relied heavily on propaganda. In the United States, posters proved most effective at influencing public opinion and maintaining morale. On the home front, they encouraged Americans to buy war bonds, write to GIs on the front, give blood, donate scrap materials to the war effort, do their best at war-production jobs (“He can’t fix guns in the air! Build ’em right! Keep ’em firing!”), and carpool to conserve gasoline (“When you ride alone, you ride with Hitler! Join a car-sharing club today!”).

One of Japan’s less successful propaganda campaigns involved a series of English-speaking women who broadcast music and misinformation to Allied troops via the radio. Servicemen nicknamed the friendly, faceless voice “Tokyo Rose.” She aimed to damage Allied morale by reporting incorrect casualty figures and tales of infidelity back home. Most servicemen paid little attention, though they did enjoy the accompanying dance music.

As in Nazi Germany, Allied propaganda posters were also used to reduce the enemy to subhuman status, thus making it easier for servicemen to kill them. In addition, the military used posters to remind soldiers of the importance of maintaining their equipment (“His rifle will fire . . . will mine? Care of arms is care of life.”) and the need to avoid careless talk (“Keep mum . . . she’s not so dumb! Careless talk costs lives!”).