On the Big Screen

Over the years, virtually every aspect of World War II has been analyzed on the big screen, from the various theaters of war to the Holocaust to life on the home front. Many movies produced during the war years were pure propaganda that played fast and loose with the facts. Hollywood is to be forgiven for this, considering the fact that wartime America went to the movies solely for escapist entertainment and cried out for heroes and happy endings, not reality. It wasn’t until after the conflict ended that Hollywood began depicting World War II in more realistic terms.

One of the most compelling and accurate war-era films was William Wellman’s The Story of G.I. Joe (1945), which Time magazine called “the least glamorous war picture ever made.” It tells the story of a typical infantry company’s battles in Tunisia, Sicily, and Italy and makes wonderful use of actual combat footage. Stars included Robert Mitchum, Wally Cassell, and Burgess Meredith as real-life war correspondent Ernie Pyle.

Harold Russell, who played a disabled soldier in the 1946 movie The Best Years of Our Lives, was a real-life soldier who lost both hands during the war. Russell received two Academy Awards for his performance in the film: one for Best Supporting Actor and a special award “for bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans.”

Hollywood has turned many of the war’s most important battles and events into epic motion pictures over the years. The Longest Day (1962), for example, is a star-studded look at the Normandy invasion that runs nearly three hours. The film’s cast reads like a Who’s Who of Hollywood, and includes John Wayne, Richard Burton, Robert Mitchum, Henry Fonda, Robert Ryan, Mel Ferrer, and Sean Connery, among many others. Ken Anna-kin’s Battle of the Bulge (1965) is equally grand in its telling of Germany’s last desperate push in the Ardennes in December 1944. Featured performers include Henry Fonda, Robert Shaw, Robert Ryan, and Dana Andrews. Also compelling is Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), a remarkably realistic look at the Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbor told from both the American and Japanese perspectives. Directed by Richard Fleischer, Toshio Masuda, and Kinji Fukasaku, the movie is highlighted by some gorgeous cinematography and stunning action footage.

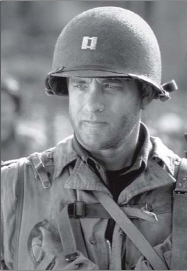

No discussion of American war movies would be complete without a mention of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998). The first twenty minutes of this movie offer a stunning recreation of the American landing on Normandy’s Omaha Beach. It’s intentionally disorienting—just like real-life combat—and agonizing to watch as soldiers are mowed down by German forces before they are even able to get out of their amphibious transports, lose limbs to enemy fire, and wade through water dyed red with the blood of their fallen comrades. Most veterans say that this sequence, which was filmed in Ireland, contains some of the most realistic combat scenes ever put on film, and the rest of the movie is equally harrowing in its depiction of war. When Saving Private Ryan premiered, the U.S. Veterans Administration offered special counseling at many VA hospitals for World War II veterans who were emotionally affected by it.

Figure 19-1 Tom Hanks in a scene from Saving Private Ryan.

Getty Images/David James/Staff

Other outstanding World War II movies include David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957); John Sturges’s The Great Escape (1963); Bryan Forbes’s King Rat (1965), based on novelist James Clavell’s experiences in a Japanese POW camp; Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One (1980); J. Lee Thompson’s The Guns of Navarone (1961); Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967); Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca (1943); William Wellman’s Battleground (1949); William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946); Franklin Schaffner’s Patton (1970); and Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1961).

Films Made During the War

War-era films of note dealing with the European and African theaters included Lloyd Bacon’s Action in the North Atlantic (1943), starring Hum-phrey Bogart and Raymond Massey; Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), a scathing parody of Adolf Hitler; Archie Mayo’s Crash Dive (1943); Billy Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo (1943); David Lean and Noel Coward’s In Which We Serve (1943); Zoltan Korda’s Sahara (1943); and Howard Hawks’s Air Force (1943).

Illustrators such as Alberto Vargas were renowned for their sexy pinups, but the most popular pinup of all was a photograph of actress Betty Grable in a white bathing suit, peering seductively over her shoulder. At the height of the war, the movie studio received 20,000 requests a week from servicemen for Grable’s photograph. Other popular pinup gals included Rita Hayworth and Jane Russell.

The Pacific theater was also a popular subject for war-era movies. Some of the best included Tay Garnett’s Bataan (1943); Edward Ludwig’s Fighting Seabees (1944), starring war film icon John Wayne; Lloyd Bacon’s The Fighting Sullivans (1942); Lewis Seller’s Guadalcanal Diary (1943); Raoul Walsh’s Objective, Burma! (1945); Mark Sandrich’s So Proudly We Hail (1943), which examines the American retreat through the Philippines to Corregidor through the eyes of three army nurses; John Ford’s They Were Expendable (1945), again starring John Wayne; and Mervyn LeRoy’s Thirty Seconds over Tokyo (1944), featuring Spencer Tracy as Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle.

Interestingly, many of Hollywood’s top directors and other creative talents made films specifically for the armed forces. One of the best known is the Why We Fight series, developed by Frank Capra and written by Julius and Philip Epstein, who also worked on Casablanca, Mr. Skeffington, and The Man Who Came to Dinner. The series was pure propaganda designed to explain to servicemen in simple terms America’s involvement in the war, and Capra pulled out all the stops, using archival photographs, animation, reenactments, and even scenes from German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl’s tribute to Nazism, Triumph of the Will. There were seven films in the series, required viewing for all servicemen headed overseas. The shorts proved so popular that they were eventually released theatrically for civilian audiences.

Many movie stars, musicians, athletes, and entertainers helped the war effort by promoting war programs, entertaining troops, and even joining the service. Famous stars who enlisted include Jimmy Stewart, Clark Gable, Raymond Massey, Burgess Meredith, Victor Mature, and Leslie Howard. Many legendary athletes also joined, including Bob Feller, Hank Greenberg, Joe DiMaggio, and Ted Williams.

Foreign Films

Many outstanding foreign films also examine various aspects of World War II. One of the finest is Wolfgang Petersen’s Das Boot (The Boat) (1981), which provides an incredible glimpse of life aboard a German U-boat. The film is wet, claustrophobic, disturbing, and utterly fascinating. On the other side of the world, Ken Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain (1959) presents an intriguing look at the war in the Pacific from the Japanese perspective. A scathing indictment of war in general, the film examines the Japanese retreat from the Philippines in the waning days of World War II through the eyes of one soldier.

Animation

The armed services also used a series of animated cartoons to teach new recruits the importance of discipline and following military regulations. One of the most memorable was the Private Snafu series, written by Ted Geisel (better known as children’s author Dr. Seuss) and Phil Eastman, and directed by legendary Warner Brothers animators Chuck Jones, Fritz Fre-leng, and others. The instructional cartoons, which relied heavily on humor to convey their very important messages, covered everything from the hazards of spreading rumors to the need for camouflage.

Many theatrically released animated cartoons from Walt Disney, Warner Brothers, MGM, and other studios also addressed the war. Perhaps best known among the dozens of cartoons produced during the war years is the Academy Award–winning Donald Duck cartoon Der Führer’s Face (1943), which mocked Adolf Hitler as a buffoon. Other wartime animated classics include Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips (Warner Brothers, 1944), in which Bugs takes on stereotypical Japanese forces; Herr Meets Hare (Warner Brothers, 1945), in which Bugs tangles with Nazi Hermann Goering by disguising himself as Hitler and Joseph Stalin; The Blitz Wolf (MGM, 1942), which features a wolf in Nazi clothing; and Swing Shift Cinderella (MGM, 1945), a war-era retelling of the classic fairy tale.

Chronicling the War

World War II was one of the most thoroughly reported military events of the twentieth century. Print and radio journalists, photographers, cinematographers, and even cartoonists captured every aspect of the war in every theater—very often at the risk of their own lives. And after the war, novelists such as Norman Mailer and Joseph Heller used their military experiences as fodder for some of the postwar era’s best fiction.

A handful of television shows have used the war as a backdrop. The best known is Hogan’s Heroes, which began in 1965. The show, featuring Allied troops in a POW camp guarded by bumbling Germans, played the war for laughs. More recently, the HBO series Band of Brothers examined the lives of soldiers in Easy Company, members of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, U.S. 101st Airborne Division.

An estimated 700 American correspondents (including twenty-four women) covered World War II for newspapers, magazines, and radio. The war was front page news almost every day, and journalists scrambled to cover stories both large and small. The Normandy invasion alone was chronicled by an estimated 500 American reporters and photographers.

Most war correspondents covered the war from the command posts, getting their information from commanding officers and military liaisons. But a great many realized that the best stories involved the soldiers fighting on the front lines, so that’s where they went, pen and camera in hand, eager to capture the sights and sounds of combat. Most of these correspondents remained relatively anonymous, but some became famous for their coverage of the war. One of the best known was Ernie Pyle, a writer for United Features Syndicate. Pyle was a friend of the common soldier and was well liked and respected by the servicemen he met and covered. So was Raymond Clapper of Scripps-Howard, whose articles were syndicated to nearly 180 newspapers throughout the United States. Sadly, both men were killed during the war: Pyle by an enemy sniper and Clapper when the plane he was riding in collided with another.

The job of war correspondent was extremely hazardous because the enemy made no distinction between journalist and soldier. A total of thirty-eight accredited war correspondents were killed by enemy fire over the course of the war, and thirty-six were wounded.

Print journalists chronicled the war, but it was radio that really brought the full horror of it into the living room of the average American. Few who heard it can forget CBS correspondent Edward R. Murrow’s solemn reporting of the Battle of Britain, conducted from the London rooftops as German bombers delivered their deadly loads. Murrow described not only the military aspect of the war in Europe but also its toll on the individual.

World War II was also the first war to be thoroughly documented in motion pictures. The U.S. military used numerous cinematographers to film battles, troop movements, and other events for later review, but Hollywood also got into the act. Indeed, some of its best known directors took camera in hand to film the action as it occurred. From this sprang an entire movie subgenre known as the war documentary. John Ford, for example, served with Major General William Donovan as head of the Field Photographic Branch and directed the documentary The Battle of Midway (1942), which combined actual battle footage with staged scenes. Ford also filmed footage from a PT boat during the Normandy invasion.

Of the many correspondents who covered World War II, none were better known than Ernie Pyle. His specialty was profiling average soldiers just trying to survive from one day to the next. Through his writing, Pyle showed America both the simple joys and the numbing horrors of World War II. Pyle’s columns were published in nearly 300 American newspapers and he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1943.

John Huston was another famous director who lent his talents to covering the war, producing Report from the Aleutians in 1943 and The Battle of San Pietro in 1944. These documentary shorts brought the graphic reality of combat home to many Americans for the first time.

War reporting was as much propaganda as it was journalism. Reports from the front were subject to military censorship, though in general there was little need to edit because most journalists believed that their job was to maintain morale as well as to report the facts. As a result, bad news, such as reports of atrocities committed by Allied forces, was so rare as to be nonexistent.

Unfortunately, racism was rampant in most news reports—as it was in almost all forms of wartime media. Japanese forces, for example, were routinely referred to as “Japs” and described as being less than human. In the years after the war, many correspondents said they had come to regret those descriptions.

The Influence of Comic Art

Most veterans of World War II have fond memories of the era’s military strips, such as Bill Mauldin’s Up Front, George Baker’s The Sad Sack, and Milton Caniff’s Male Call. To servicemen everywhere, they were as coveted as dry socks and mail from home. But these weren’t the only cartoons to address the war. Many popular civilian strips aided the effort equally well on the home front by boosting morale, maintaining a strong sense of patriotism, and encouraging Americans to do their part by buying war bonds, limiting travel, and contributing to scrap drives.

“People were swept up in a sense of common purpose,” recalls Will Eisner, a comic book artist who used his talents during the war to create instructional cartoons for the U.S. Army. “It was by common consent that we were in the war, and no daily strip dared make an antiwar remark. All of the civilian strips were involved in promoting the war effort because we had an enemy that had to be defeated.”

The smoke from the attack on Pearl Harbor had barely cleared when the comics’ most beloved characters lined up to enlist. One of the first was Joe Palooka, who refused a commission (he felt he wasn’t smart enough to be an officer) and spent the entire war as a buck private. It was an act that prompted countless men to sign up.

There were many others: Terry of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates became a flight officer with the air force, and his mentor, Pat Ryan, a lieutenant in naval intelligence. Roy Crane’s Captain Easy helped the FBI fight spies and saboteurs when war broke out in Europe, and after Pearl Harbor the character became a captain in the army. Even Russ Westover’s Tillie the Toiler did her part by joining the WACs, her ditzy personality quickly replaced by patriotic duty.

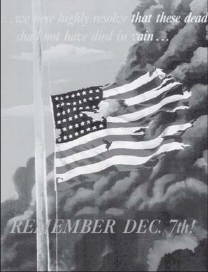

Figure 19-2 War poster by Alan Saalburg.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives (44-PA-191)

There seemed to be a general agreement among most artists that they would keep readers entertained. They didn’t want to remind people of the war. They wanted to reassure them that some things would continue as they always had.

The military comic strips that appeared in Stars and Stripes, camp papers, and stateside publications were also a tremendous morale booster—both for fighting forces and their families back home, say cartoon historians.

Comic books became one of the most popular forms of reading material on military bases during the war. They were much more gung-ho than the daily strips, which made them the perfect medium for war-era propaganda. Japanese were usually depicted as short, buck-toothed, slant-eyed devils, and the Nazis as war-mongering beasts—perfect foils for peace-loving superheroes, generally good-looking white Americans.

Morale Boosters

The strips were also a heartfelt tribute to the forces in the trenches, who often saw their daily frustrations and anxieties humorously illustrated. “The military strips were definitely good for morale because the soldiers saw their own experiences in them,” cartoonist Mort Walker adds.

One of the best at finding that “universal truth” was Bill Mauldin, whose generic dogfaces, Willie and Joe, experienced everything good and bad that the war had to offer. Up Front was especially popular with the average foot soldier because he knew Mauldin was right there on the front lines with him, not sitting on his butt in the Stars and Stripes office.

Also popular with servicemen was Sergeant George Baker’s The Sad Sack, which premiered in Yank magazine in May 1942. A former animator for Walt Disney, Baker conceived of the weekly humor strip based on his experiences and those of his fellow soldiers. “The underlying story of the Sad Sack,” Baker noted during the strip’s heyday, “was his struggle with the Army in which I tried to symbolize the sum total of the difficulties and frustrations of all enlisted men.” Baker succeeded well. In one infamous strip, Sad Sack watches a military hygiene film so graphic that he puts on rubber gloves to shake hands with another serviceman’s girlfriend.

Other humorous military strips included Leonard Sansone’s The Wolf and Dick Wingert’s Hubert.

Dave Breger, who had been doing a strip for the Saturday Evening Post titled Private Breger, changed the name to G.I. Joe in 1942 for Yank magazine and Stars and Stripes, thereby coining one of the most famous terms to come out of the war. The character was essentially the same in both military and civilian versions, and remained popular even after the war.

While Up Front illustrated the daily grind of frontline duty and The Sad Sack and others showed the more humorous side of military life, Milton Caniff’s Male Call was something different altogether: a pinup strip whose main character, the sexy and sublime Miss Lace, constantly reminded its readers what they were fighting for.

Servicemen in all theaters of the war relied on pinups—photographs, illustrations, and cartoons of beautiful women—to remind them of what was waiting back home. Though the military sometimes tried to censor the pinups, they proliferated at a remarkable rate and could be found tacked up on barracks walls and in soldiers’ wallets worldwide.

Male Call

Caniff was a dedicated patriot who deeply loved his country, but phlebitis kept him from serving during the war. Caniff glorified the war effort in Terry and the Pirates, but he also wanted to do something special for the servicemen. He pitched to the military a light-hearted strip specifically for camp papers, and Male Call was born. The strip premiered in 1942 (at first featuring the sultry Burma from Terry and the Pirates) and by the end of the war was appearing in nearly 3,000 publications. Caniff neither asked for nor received any payment for the strip, which he drew during his lunch hour and other rare moments of free time.

The United States was not the only country to use comic art as a propaganda device. The Nazis used vicious caricatures to turn national sentiment against the Jews and other minorities. Even American comic-book characters were fair game; Das Schwarz, a Nazi propaganda organ, went so far as to brand Superman as Jewish in an effort to discredit the Man of Steel.

Miss Lace, the star of Male Call, was a dark-haired beauty with model Bettie Page bangs who dressed as seductively as Caniff could get away with. She was every serviceman’s pal, and the readers adored her.

Male Call ended in 1946, but Caniff continued to draw Miss Lace for military reunion programs for years afterward.