Chapter 2: South Korea in Depth

Introduction

The history of the Korean Peninsula spans more than 5,000 strife-filled years. That’s ironic for a place that has been called the “Land of the Morning Calm.” But because of its strategic location, the peninsula suffered a seemingly endless series of invasions by China and Manchuria from the north and Japan from the east. In fact, the last war, the Korean War, never actually ended—rather, it was halted by a ceasefire in 1953. That solidified a historic split, with a communist dictatorship ruling the North and a more democratic regime ruling the South. The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the area that marks the boundary between the two Koreas, is a painful reminder of the country’s war-torn past.

While North Korea has suffered poverty and famine, South Korea has made incredible strides in the past few decades in its race toward modernization. South Korea, a country roughly the size of Great Britain, is the 15th-largest economy in the world. The city of Seoul, with its towering high-rises and modern infrastructure, is a testament to the innovative spirit of the Korean people.

South Korea Today

Touted as one of the most wired (or shall we say, “wireless?”) countries in the world, it’s no surprise to see everyone from toddlers to grandpas texting with their smartphones on the subway. These technological advancements have not only made South Korea more prominent on the world map, but its electronics, cars, and even textiles have spread worldwide. This export of Korean goods even includes cultural phenomena, like the rise in popularity of Korean TV dramas, films, and KPop around the world.

With the opening up of the world market to Korean goods, South Korea, in return, has imported much from other countries, especially from the West. This can most easily be seen in the American fast-food chains that dot the urban landscape. However, this also means that Korea’s global cuisine has come a long way. In a country where even a hamburger was hard to come by, you can now find crispy Neopolitan pizza fresh from wood-burning stoves, schwarma vendors on the street, and even get a croissant that tastes almost like it’s come out of a Parisienne boulangerie.

Although the global economic downturn has affected South Korea, too, you would not be able to tell with all of the new road projects and construction going on in the country. Still, traces of tough economic times can be seen in empty storefronts and high-end restaurants with fewer occupied tables.

Unpredictable weather in South Korea and other parts of the country has driven up food prices, although it’s difficult to tell the domestic problems, since prices remain generally stable due to the influx of cheap crops from China.

The price of gas remains high (averaging around ₩1950 per liter) so travel costs have increased. Still, public transportation remains affordable throughout South Korea.

As the country moved by leaps and bounds toward the technological age, some of the traditions and traces of its past were overtaken. However, in the past few years, the government has taken steps to try and preserve the architectural and natural resources that remain. Outside the large cities, you can still see older folk farming in the fields, making kimchi (a spiced dish) in the fall, and picking fruit by hand on the hillsides, they just happen to do it now on paved roads, mobile phones in hand.

The Making of South Korea

Prehistory

Before humans settled on the Korean Peninsula, dinosaurs left fossils and other evidence. You can still see their footprints and fossilized eggs on the shores of Goseong. The first human beings on the peninsula can be traced as far back as the Paleolithic period (about 500,000 years ago). Researchers believe that Neanderthals lived here until Paleo-Asiatic people moved in around 40,000 b.c. Very little is known about the Paleo-Asiatics, but the tools and other relics they left behind suggest that they were hunter-gatherers who also fished. It is very likely that these early inhabitants of the Korean Peninsula moved to what is now Japan about 20,000 years ago, when the Korea Strait was narrower and easier to cross.

Archaeological remains suggest that nomadic Neolithic tribes migrated from central and northeast Asia (mostly Mongolia, China’s Manchu region, and southeast Siberia) to the Korean coastline around 8,000 b.c. These are the ancestors of modern Koreans, and they are responsible for the earliest versions of Korean culture and language (the Tungusic branch of the Ural-Altaic language group). Traces of these Neolithic and older cultures can be seen in the goindol (dolmen/megalithic stone tombs) scattered throughout the land. In fact, the largest concentration of dolmen in the world is found on the Korean Peninsula. The easiest to access from Seoul is in Ganghwa-do, but more can be seen around Gochang and Hwasun.

In around 3,000 b.c. a larger wave of immigrants from the same areas brought more developed pottery and better tools. These new arrivals contributed to the founding of small villages of pit dwellings. With the domestication of animals and the development of farming, these tribes ventured farther inland and became increasingly less nomadic. Clans developed around the start of the Bronze Age.

However, Korean history is generally considered to start with the birth of King Dang-gun in 2333 b.c. Legend has it that Dang-gun was born of a son of Heaven and a woman from one of the bear-totem tribes (shamanism was predominant in ancient Korean religions). He established the GoJoseon (Old Joseon) Kingdom, which literally translates to the “Land of the Morning Calm.” This walled kingdom was located near present-day Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea.

The Three Kingdoms

By the first century b.c., three dominant kingdoms had emerged on the peninsula and part of what is now Manchuria. The first and largest was Goguryeo (37 b.c.–a.d. 688), in the northern part of the peninsula, encompassing part of Manchuria and what is now North Korea. It served as a buffer against aggression from China. Baekje (18 b.c.–a.d. 660) developed in the southwestern part of the peninsula and Shilla (57 b.c.–a.d. 935) in the southeastern section. This time is known as the Three Kingdoms period, even though a fourth, smaller kingdom, Gaya (a.d. 42–532), existed between Shilla and Baekje in the southern part of the peninsula.

Traces of Baekje history can be seen in its old capitals, the now small towns of Gongju, and, especially, Buyeo.

Goguryeo was the first to adopt Buddhism in a.d. 372. The Baekje Kingdom followed in 384. Shilla was later and did not adopt the religion until 528. The three kingdoms had similar cultures and infrastructures, based on Confucian and Buddhist hierarchical structures with the king at the top. Legal systems were created, and Goguryeo annexed Buyeo while Shilla took over Gaya. The kingdoms became refined aristocratic societies and began competing with each other in development of Buddhist–Confucian power and an eye toward territorial expansion.

Unified Shilla

The Shilla Kingdom developed a Hwarang (“Flower of Youth”) corps, a voluntary military organization for young men, in the 600s. This popular movement helped build up Shilla’s military strength. The kingdom was also looking outward, learning from its neighboring kingdoms and building amicable relations with the Tang Dynasty in China.

In the meantime, Goguryeo was in fierce battle with Tang China and the Sui emperor, with heavy casualties on both sides. Tang China eventually turned to Shilla for help. The Shilla–Tang forces were able to defeat Goguryeo and its ally Baekje, but Tang wasn’t about to let Shilla have control of the land. Chinese officials took the Baekje king and his family to Tang and appointed a military governor to rule Baekje territory. Goguryeo’s king and hundreds of thousands of prisoners were also taken to China. Shilla launched a counterattack against China and retook all of Baekje. In 674 China invaded Shilla, but the kingdom was able to defend itself, forcing the Tang army out of Pyongyang. Still, the Chinese forces were able to hold onto part of the Goguryeo kingdom, which is now Manchuria.

The Shilla Kingdom officially unified the peninsula in 668. Despite some turbulence, the Unified Shilla period (668–935) maintained close ties to China and its culture. Many Shilla monks traveled there to study Buddhism and bring back their cultural learnings. During this cultural flowering, there were new technological innovations, including the world’s oldest astronomical observatory which was constructed in Gyeongju, the Shilla capital. The town of Gyeongju is like one large outdoor museum, preserving the history of Shilla in its temples, shrines, and grassy royal tombs.

Goryeo Dynasty

At the end of the 9th century, the Shilla Kingdom had grown weak and local lords began fighting for control. It was a period of civil war and rebellion. In 918, Wang Geon, the lord of Songak (present-day Gaesong), defeated the other warring lords and established the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392). Goryeo, a shortened version of the former Goguryeo kingdom, is where the name Korea came from.

New laws were created based on Chinese law as well as Buddhist and Confucian beliefs. During a period of relative peace, culture flourished under the Goryeo aristocracy. Goryeo celadon pottery was developed (see Celadon Museum, ); the Tripitaka Koreana, a set of more than 81,000 wood blocks used to print the Buddhist canon, was created (see Haeinsa, ); and the first movable metal type was invented. As the official religion, Buddhism flourished under Goryeo rule—new temples were built, wonderful paintings were commissioned, and various manuscripts were created.

Unfortunately, peace didn’t last long. Although Goryeo was able to thwart attacks early on, in the 12th century it suffered internal conflicts, with civilian and military leaders fighting for control. In the 13th century, the peninsula was invaded several times by the Mongolians; traces of their invasion can be seen in the distinct type of horses on Jeju-do. Luckily for Goryeo, Mongol power declined rapidly from the middle of the 14th century on, giving the kingdom some respite, though it did not quell the conflicts brewing internally. At the same time, Japanese pirates started becoming more sophisticated in their military tactics. General Yi Seong-gye was sent to fight both these pirates and the Mongols, and his victories helped him consolidate power. He forced the Goryeo king to abdicate and named himself King Taejo (“Great Progenitor”), the first emperor of the Joseon Dynasty.

Joseon Dynasty

When the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) was founded, King Taejo created a Confucian form of government that promoted loyalty to the country and respect for parents and ancestors, and in 1394 he moved the capital to what is now Seoul, where many of the palaces and the Jongmyo, the family’s royal shrine, still stand. His family, the Yis, ruled what was to become one of the world’s longest-running monarchies.

Again, Korea flourished both artistically and culturally, and major advances in science, technology, literature, and the arts were made. One of the most celebrated emperors of the time was King Sejong the Great, who took the throne in 1418. He gathered a team of scholars to create Korea’s first written language, Hangeul.

From 1592 to 1598, Korea was attacked relentlessly by Japanese aggressors during what is called the Imjin Waeran and is sometimes referred to as the Hideyoshi Invasions. Successive attacks by its eastern neighbor and Qing China from the north led to the country’s increasingly harsh isolationist policy. By the time Admiral Yi Sun-shin (see Yeosu, ) and his fleet of iron-clad “turtle” ships had fended off the Japanese for good, Korea had shut itself off completely from the rest of the world. It became known as the Hermit Kingdom, and it managed to remain relatively untouched by outsiders until the 1800s.

Floating Turtles

Korea’s most famous naval commander, Admiral Yi Sun-shin, led the navy against Japanese invasion during the wars of 1592 to 1598. Legend has it that the admiral, who was killed during a skirmish in 1598 at the age of 43, never lost a single one of the 23 battles he commanded. But he may be most famous for his use of turtle ships, boats armored with thick wood planking, iron shields, and spikes that the Korean navy used to inflict heavy damage on invading Japanese ships. Capable of ramming other ships without sustaining damage, these turtle ships are considered one of the triumphs of Korean ingenuity.

Japanese Occupation

In the 19th century, Korea again became the focus of its imperialist neighbors, China, Russia, and Japan. By 1910, Japan, which had been exerting more and more control over Korea’s destiny, officially annexed the country, bringing an end to the Joseon Dynasty. The Japanese tried to quash Korean culture, not allowing people to speak their own language, and attempted to obliterate Korean history.

When King Gojong, the last of the Joseon rulers, died, anti-Japanese rallies took place throughout the country. Most notably on March 1, 1919, a declaration of independence was read in Seoul as an estimated two million people took part in rallies. The protests were violently suppressed, and thousands of Koreans were killed or imprisoned (see Seodaemun Prison, ). But independence-minded Koreans were not deterred, and anti-Japanese rallies continued until a student uprising in November of 1929 led to increased military rule. Freedom of expression and freedom of the press were severely curbed by Japanese rule.

A Korean government in exile was set up in Shanghai and it coordinated the struggle against Japan. On December 9, 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the exiled Korean government declared war on Japan. On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied forces, ending 35 years of Japanese occupation. Ten days later Korea became one of the earliest victims of the Cold War: It was divided in half, with the United States taking control of surrendering Japanese soldiers south of the 38th Parallel, while the Soviet Union took control of the areas north. The division was meant to be temporary, until the U.S., U.K., U.S.S.R., and China could come to an agreed-upon trusteeship of the country.

The Korean War

A conference was convened in Moscow in December 1945 to discuss the future of Korea. A 5-year trusteeship was discussed and the Soviet–American commission met a few times in Seoul, just as the chill of the Cold War began to set in. In 1947, the United Nations called for the election of a unity government, but the North Korean regime, dominated by the Soviet Union, refused to participate, and the two countries were formally established in 1948.

But on June 25, 1950, North Korea, aided by the communist People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union, invaded the South. The South resisted with help from United Nations troops, most of whom were American. Fighting raged for 3 years, causing much damage and destruction. The war has never officially ended, but the fighting stopped with the signing of a ceasefire on July 27, 1953, creating the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ, ).

Recent History

The Republic of Korea officially became a country on August 15, 1948. Its history after the Korean War has been marked by turbulent governments. The country has undergone five major constitutional changes, along with decades of authoritarian governments and military rule. Although an electoral college was created in the 1970s, South Korea did not hold its first democratic and fair presidential election until 1987. Despite its violent past, South Korea grew by leaps and bounds, especially in the decades from the 1960s to the 1990s. It is now the 4th-largest economy in Asia and the 15th-largest in the world. It is also one of the most wired countries in the world.

The president is the head of state of the Republic of Korea and is elected by direct popular vote for a 5-year term (with no possibility for re-election). As South Korea’s first president, Rhee Syngman took power in 1954 with an anticommunist platform, but his administration collapsed in the face of a student antigovernment movement, the 4.19 (April 19th) Revolution, in 1960. In 1963, Park Chung-hee was elected president, and he ruled with military might until he was assassinated by his own men in 1979 (Im Sang-Soo’s film, The President’s Last Bang, is an excellent satire of the assassination). In 1980, Chun Doo-hwan came to power and continued his predecessor’s authoritarian rule until a massive 1987 protest demanding democracy. At that point, Roh Tae-woo came to power, the country hosted the 1988 Olympics, and it joined the United Nations in 1991. Kim Young-sam became the country’s first nonmilitary president in 1993 and saw the International Monetary Fund (IMF) collapse during his presidency. In 1997, Kim Dae-jung was elected and made efforts toward reviving the economy, and he hosted the FIFA World Cup in 2002. The 16th president of South Korea, Roh Moo-hyun, was elected in 2003 and committed suicide in May 2009, when he was embroiled in a bribery scandal.

After one of the lowest voter turnouts in history, Lee Myung-bak of the conservative Grand National Party was elected president in 2007. The largely unpopular President Lee was the former CEO of Hyundai and served as the mayor of Seoul. Lee’s term runs from 2008 to February of 2013.

With the surprise death of Kim Jong-Il in 2011, there is uncertainty as Kim Jong-eun has taken helm as the Supreme Leader of North Korea. South Koreans are somewhat used to this opaqueness from their neighbor and everyday life is largely unaffected by changes in the north.

Art & Architecture

Arts

Ceramics

The earliest form of art found on the Korean Peninsula is pottery. Pottery shards from the Neolithic era are prevalent. By the time of the Three Kingdoms, ceramics were in common use in everyday life. But it was during the Unified Shilla period that the pottery began taking on interesting shapes and decorative patterns.

In the Goryeo period, a ceramics culture evolved, with the creation of cheongja (celadon) pottery. In the Joseon era, the white ceramics of baekja and buncheongsagi were developed. Unusually, Joseon ceramics were simpler in design than those from the Goryeo period. Of course, the tradition of Korean ceramics continues today and can be seen throughout the country, especially in Icheon, where you can see Korea’s potters solidify their clay creations in traditional firewood kilns.

Painting

The earliest known Korean paintings are murals found on the walls of tombs from the Three Kingdoms period (although painted baskets were found in the area of the ancient Lelang kingdom around 108 b.c.). The ones from Goguryeo were more dynamic and rhythmic, while those of Baekje were refined and elegant. Those from Shilla were meticulous. Unfortunately, only one example survived from the Unified Shilla period.

During the Goryeo period, painting flourished with the heavy influence of Buddhism, as shown in murals in temples and religious scroll paintings. No examples of secular paintings remain from this time, but writings talk about them and Koreans often traveled to China to buy paintings.

The rise of Confucianism during the Joseon period had a profound effect on Buddhist painting, and it has not enjoyed such artistic prominence since the Goryeo period. Paintings during this time were influenced by works of Chinese scholar-artists. The 17th century saw less of an effect of China on Korea, due to successive invasions from the Japanese and Manchus, and it was during the 18th century that Korean painting finally came to its own. Examples of this are the development of the chingyoung sansu (“real landscape”) style and depictions of everyday life.

During the Japanese occupation, Korean painting suffered, but the introduction of modern Western painting styles influenced Korean artists. After World War II, an interest in both Western and traditional styles grew rapidly and today both continue to flourish.

Sculpture

The oldest known sculptures in Korea are some rock carvings on a riverside cliff, Ban-gudae, in Gyeongsangbuk-do. Smaller sculptures were made of bronze, earthenware, and clay during the Bronze Age. The art form, however, did not gain prominence until the introduction of Buddhism during the Three Kingdoms period. Buddhist images and pagodas became the main forms for sculptors during this time. Buddhas from Goguryeo had long faces on mostly shaven heads and were characteristic of the more rough style of the kingdom. Baekje Buddhas had more human features and stately but relaxed bodies with more volume beneath the robe. Early Shilla sculptures showed influences of Sui and Tang China, with round faces and realistically depicted robes.

Buddhist sculpture continued to be popular during the Goryeo period. A large number of pagodas and Buddhas were created with more Korean facial features, but stiffer bodies. Of course, Buddhist sculpture suffered during the Joseon period and declined even more under Japanese rule, when Korean sculptors began just imitating Western styles. Modern Korean sculpture came into its own in the 1960s, and contemporary Korean sculpture continues to develop today.

Architecture

Several architectural remains from Neolithic culture exist on the peninsula. Dolmens, primitive tombs of important people from ancient times, are found all over the southern areas of Korea. Other ancient structures of interest are the royal tombs from the Baekje and Shilla eras. One interesting thing of note is that evidence of ondol, the uniquely Korean system of under-floor heating, can be found in primitive ruins.

In general, historical Korean architecture can be divided into two broad styles—one used for palaces and temples and the other for houses of common people.

The natural environment was always an important element of Korean architecture and when choosing a site for building, Koreans gave it careful consideration. An ideal site had appropriate views of the mountains and water and aligned with traditional principles of geomancy.

The ideal hanok (traditional house), for instance, is built with the mountains to the back and a river in the front. The homes were built with ondol underneath for the cold winters and a wide daecheong (front porch) for keeping the house cool during the hot summers. In the colder, northern areas, homes were built in a closed square to retain better heat, while homes in the central region were generally L-shaped for better airflow. Houses in the southern region were built in an open I-shape for even more airflow.

Traditional homes of upper-class people, or yangban, took into consideration Confucian ideas, separating living quarters by the age and gender of the occupants. Males older than 7 slept in the sarangchae (the study and drawing room for the men), while women and children (and sometimes married couples) slept in the anchae, which was a place in the inner part of the home to restrict the movement of women. The servants slept in the haengnang and the ancestors were honored in the sadang. The buildings had tiled roofs and were often called giwajib. The entire complex was housed within stone walls with a large main gate/front door, daemun. Although not homes, per se, examples of yangban architecture can be seen in seowon, Confucian academies, such as Dosan Seowon.

Lower-class homes had a much simpler structure of a large main room, a kitchen, and a porch. The houses were simple, with thatched roofs made of straw or bark. Examples of these can be seen in the Korean folk village of Suwon or Andong.

South Korea in Pop Culture

Books

Although classic texts and popular English-language literature are often translated into Korean, the reverse is not true. Very few Korean books are translated into English. However, the newer generations of Korean immigrants, foreign-born Koreans, and non-Koreans are writing interesting books about the culture.

Non-fiction books on Korea include the following: 20th Century Korean Art (2005) by Youngna Kim is a solid introduction to contemporary works by current artists. Korean Folk Art and Craft (1993) by Edward B. Adams, although a bit dated, is an excellent guide to understanding Korea’s folk objects. Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (2005, updated edition) by Bruce Cumings is an excellent overview of the history of the peninsula. Korea Style (2006) by Marcia Iwatate and Kim Unsoo is perhaps the only book in English about Korean architectural and interior design, highlighting 22 homes in the country. Eating Korean: From Barbeque to Kimchi, Recipes from My Kitchen (2005) is a friendly guide to Korean cuisine. Written by the author of this guide, it includes personal stories and over 100 recipes. Quick and Easy Korean Cooking (2009), also written by this book’s author, introduces Korean flavors into your home kitchen.

There are some good Korean fictional works translated into English, available on limited release: Between Heaven and Earth (1996/2002) was the winner of the Yi Sang Literature Prize in 1996. It’s a story about a transient relationship between a man on his way to a funeral and a woman he meets on the way. The Wings (2004) by Yi Sang is a collection of three semiautobiographical short stories on life, love, and death. The Rain Spell (1973/2002) by Yun Heung-gil is a touching and sad story about the Korean War. House of Idols (1960/1961/1966/2003) by Cho In-hoon is about two soldiers in Seoul after the Korean War. It includes “End of the Road,” a story about a prostitute set around a U.S. military base. The Land of the Banished (2001) by Cho Chong-rae is about a peasant family during the Korean War. It depicts the class struggle and describes the People’s Army. It’s Hard to Say: Buddhist Stories Told by Seon Master Daehaeng (2005) is an illustrated introduction to Seon (Zen) teachings, with fun stories for adults and children. Meeting Mr Kim: Or How I Went to Korea and Learned to Love Kimchi (2008) is the story of how an English writer, Jennifer Barclay, traveled around South Korea for three months, often well off the beaten track, with a tent and backpack, meeting people as she went and discovering a unique culture she had previously known nothing about. In spite of having arrived in Korea with a rock band, her journey becomes something of a spiritual one as she learns about Buddhist temples. It’s an accessible and sometimes funny introduction to the country, offers inspiration on places to visit beyond the city of Seoul, and illustrates what a welcoming country it really can be.

Films

Since the late ’90s, South Korean films have been gaining international recognition and winning prizes at festivals worldwide. Though not comprehensive by any means, the following is a list of films we’ve found notable in the past decade or so.

Hahaha (2010) won Hong Sang-soo a prize at Cannes for his usual narrative tricks of showing the same events told from different perspectives. His 2005 Tale of Cinema and his 2008 Night and Day are also standouts in his repertoire.

Actresses (2009) is a star-studded “documentary” of a supposed Vogue Korea photo shoot of the country’s lead actresses on New Year’s eve. The director, Lee Je-yong plays with the documentary form while letting the sharp wit of the actresses themselves shine through the loosely structured script.

Treeless Mountain (2008) is an unsentimental story of a girl (age 6) who must take care of her younger sister after their mother leaves them with an aunt to search for their father. This story of childhood resilience was written and directed by one of South Korea’s few women directors, So Yong Kim.

Secret Sunshine (Miryang; 2007) is Lee Chang-dong’s film about a woman trying to start a new life in a small town, Miryang (hence the name). The performance by Jeon Do-yeon won her the best actress prize at Cannes, but her co-star, Song Kang-ho, also does an excellent job of portraying a certain type of universal, small-town Korean man.

The President’s Last Bang (2005), directed by Im Sang-soo, is a controversial political satire dramatizing the last days of President Park Chung-hee. His military dictatorship ended in 1979 with his assassination by his own men. The Korean title translates literally to “Those People at That Time.”

Oasis (2002), an award-winning film by Lee Chang-dong, is about a relationship between an ex-convict and a woman with cerebral palsy. The brilliant acting by Moon So-ri garnered her the Marcello Mastroianni Award at Venice that year. Lee’s Peppermint Candy (2000), though not a brilliant work of art, is an interesting historical drama depicting the Korean psyche, through one man’s story told backward from the end of his life to his youth.

Spring in My Home Town (1998) is a slow-moving but nicely told story by director Lee Kwangmo about two 13-year-old boys in a small village during the last days of the Korean War. The film’s Korean title is “The Beautiful Season.”

Farewell, My Darling (1996), written and directed by Park Cheol-Su (director of 301/302), is about a family mourning the death of its patriarch. It is an excellent commentary on the contradictions and commingling of Confucius traditions and modern life in Korea.

TV

The wildly popular television drama Winter Sonata (the second half of the show Endless Love) was one of the shows responsible for the “Korean wave” (or Hallyu) that swept through the rest of Asia in the early 2000s and popularized Korean TV shows worldwide.

There are literally hundreds of dramas to choose from, so it’s difficult to recommend titles. The most popular ones from the past few years have been My Girl, Secret Garden, 49 Days, Iris, Full House, City Hunter, and Heartstrings. Also, historic dramas, like Deep-rooted Tree (based on the novel of the same name, dramatizing the story of King Sejong and the creation of the Korean written language) and Queen Seon-deok (written by the screenwriter of Jewel in the Palace, telling the story of the first female ruler of the Shilla Kingdom), although fictionalized, are an entertaining way to learn more about Korea’s colorful history. You can even visit some of the sets built specifically for productions. We’ve included details of these throughout the book.

YesAsia (www.yesasia.com) is an excellent online source for Korean dramas with English subtitles.

Music

You may have heard of the KPop, made popular by Rain or even heard KPop groups in some clubs overseas. Of these, female vocalist Boa is one of the few who have been able to make a crossover album in English. Still, Korean pop singers and performers rise and fall so quickly it’s hard to keep track. Kpopmusic.com, allkpop.com, and kpopseven.com are good sources for checking out the latest hits and bands.

Despite the temporary nature of today’s pop music in South Korea, the country’s musical roots go back centuries, back to its shamanistic roots. Korea’s traditional music grew from some outside influences (for example, Buddhism), but had its own origins. Special court music and ensembles were performed for royalty and aristocrats. Although it dates back to the beginning of the Joseon Dynasty, it’s very rare to be able to catch a court music performance these days, aside from special events put on by the National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts.

At the other end of the spectrum were the folk musicians, who traveled from town to town putting on impromptu concerts for commoners. The villagers would throw the roving musician a few coins or feed them in return for the entertainment.

Pungmul is a type of folk music tradition that grew from shamanistic rituals and Korea’s agricultural society. A pungmul performance is led by drumming, but includes wind instruments as well as dancers. Because it’s a kinetic, colorful performance, a recording of pungmul music rarely does it justice. However, samul nori, which also has its roots in nog-ak (farmer’s music), makes use of four of the drums found in pungmul. Each drum represents various elements of weather—rain, wind, clouds, and thunder. It’s a good entry into Korean traditional music, especially for those who like percussion. They have occasional performances at a variety of places around the country, including the Korean Folk Village in Suwon ().

Pansori is one of the most famous types of traditional performance. Sometimes called the Korean “blues” (not because of the style but more because of the sadness in the music), pansori is a long, drawn-out performance by one singer and one accompanying drummer. The lyricist tells a narrative song, inviting audience participation and joke telling along the way.

Sanjo (which translates literally as “scattered melodies”) is one of the most advanced forms of Korean music. It describes a solo performance on a traditional instrument in which the performer begins slowly, but builds up to a faster, more spontaneous tempo, adding improvisations and showing off his or her skills with each successive movement. In an entirely instrumental performance, the rhythms shift as the performance progresses. There are sanjo for piri (bamboo oboe), daegeum (bamboo flute), haegeum (two-string bowed instrument), ajaeng (bowed zither), geomungo (six-stringed zither), and the gayageum (12-stringed zither).

A modern gayageum master was Hwang Byungki (www.bkhwang.com), who played both traditional and original compositions on the Korean zither. His album The Labyrinth (2003) contains some of the most experimental of his works, while Spring Snow (2001) is a more meditative and minimal interpretation.

A celebrated performer of the daegeum is Yi Saeng-gang (www.leesaengkang.com). His album Daegeum Sori (2007) is an excellent introduction to the sounds of the bamboo flute, but his Sound of Memory Vol. 2 is a more haunting study of the bamboo instrument.

Eating & Drinking

Korean cuisine encompasses foods from the land and the sea. You can enjoy a simple bowl of noodles, a 21-dish royal dinner, or anything in between. From a humble vegetarian meal at a Buddhist temple to elaborate banquets in Seoul’s most expensive restaurants, South Korea has something for even the pickiest of eaters.

Koreans enjoy dishes with bold flavors, such as chili peppers and garlic, but usually traditional royal cuisine and temple food is not spicy. Each town in the country is famous for a certain dish, a regional specialty, seafood, or a particular fruit or vegetable that is grown in the area.

The Korean Table

A Korean meal is usually made with balance in mind—hot and cool, spicy and mild, yin and yang. At the core of every meal is bap (rice), unless the meal is noodle- or porridge-based. Koreans don’t distinguish between breakfast, lunch, or dinner, so it’s not unusual to eat rice three times a day.

In addition to individual bowls of rice, you may get a single serving of soup. Hot pots (jjigae or jungol), which are thicker and saltier, are set in the middle of the table for everyone to share. Because beverages are rarely served during a traditional Korean meal, there should always be a soup or water kimchi (see box below) to wash the food down (although as a foreigner you’ll almost always be offered filtered or bottled water with your meal).

Speaking of kimchi, there will usually be at least one type on the table. Often there are two or three kinds, depending on the season. Served in small dishes, kimchi helps add an extra kick to whatever else is on the menu. Like the rest of the food, kimchi is laid out in the middle of the table for everyone to share.

What Is Kimchi?

Kimchi is a spicy dish, the most popular of which is made from fermented cabbage, and it is a source of national pride for South Koreans. When hungry, any Korean would swear that a bowl of rice and some kimchi are all that’s needed to complete a meal. The most popular type is the traditional version made from napa cabbages, called baechu kimchi. Not only is kimchi eaten as a side dish, it is also used as an ingredient in other dishes. For instance, there is kimchi bokkeum bap (fried rice with kimchi), kimchi jjigae (a hot pot of kimchi, meat, tofu, and vegetables), kimchi mandu (kimchi dumplings), kimchi buchingae (kimchi flatcakes), kimchi ramen (kimchi with noodles)—the list is endless. Koreans love their kimchi so much that many homes even have separate, specially calibrated refrigerators designated just to keep kimchi fresh. When taking a photo, Koreans say “kimchi” instead of saying “cheese.” If you like spicy, salty food, be adventurous and try some kimchi. You’ll have over 167 varieties to choose from!

Mit banchan—a variety of smaller side dishes, anything from pickled seafood to seasonal vegetables—rounds out the regular meal. In traditional culture, the table settings varied depending on the occasion (whether the meal was for everyday eating, for special occasions, or for guests) as well as the number of banchan (side dishes) on the table. The settings were determined by the number of side dishes, which could vary in number—3, 5, 7, 9, or 12. As with all Korean food, the royal table was different from the commoner’s.

There are no real “courses” per se in Korean meals. Generally, all the food is laid out on the table at the same time and eaten in whatever order you wish. If you order galbi (ribs) or other meat you cook yourself on a tabletop grill, your rice will arrive last so that you don’t fill yourself up too fast. When you have hwae (raw fish), you will be brought a starter, the fresh fish (quite often the fish is netted for you fresh from a tank), and then a mae-un-tahng (spicy hot pot) made from whatever is left of your fish. Also, there is no such thing as dessert in Korean tradition; however, an after-dinner drink of hot tea or coffee is generally served with whatever fruit is in season.

Korean meals were traditionally served on low tables with family members sitting on floor cushions. Some restaurants still adhere to this older custom, but others offer regular Western-style dining tables. Although certain traditions have gone by the wayside, mealtime etiquette still applies, especially for formal meals.

For starters, you should always wait for the eldest to eat his or her first bite, unless you are the guest of honor—if you are, then everyone will be waiting for you to take your first bite before digging in. Koreans usually eat their rice with a spoon, not with chopsticks. Unlike in other Asian countries, rice bowls and soup bowls are not picked up from the table. Completely taboo at the dining table is blowing your nose, chewing with your mouth open, and talking with your mouth full. Leaving chopsticks sticking straight out of a bowl (done only during jesa, a ritual for paying respect to one’s ancestors), mixing rice and soup, and overeating are also considered inappropriate. During informal meals, however, these rules are often broken.

For a list of popular menu items in Korean and English.

Sweet Goldfish & Silkworm Casings: Street Food

Wandering around the streets of South Korea, you can eat your fill without setting foot in a restaurant. You can choose from a wide variety of venues and dishes—everything from little old ladies roasting chestnuts on the street corners (only in the winter) to pojang macha (covered tents), where you can get a beer or soju (rice or sweet potato “vodka”), too. Typical fare includes the following:

• Dduk bokgi—seasoned rice cake sticks that are spicy, a little sweet, and a lot tasty

• Boong-uh bbang—goldfish “cookies” filled with sweet red-bean paste (also available round with a flower print or in other shapes)

• Ho-ddeok—flat, fried dough rounds filled with sugar

• Soondeh—Korean blood sausage

• Gimbap—rice and other things rolled in seaweed (also available in miniversions)

• Yut—hard taffy usually made from pumpkin (may be rough on your fillings!)

• Bbundaegi—boiled silkworm casings, a toasty treat for the adventurous

• Sola—tiny conch shells

When to Go

South Korea has four distinct seasons, and the best times to visit are in the spring and fall, since summers are hot and humid and winters are dry and cold—though the mountainous terrain makes for great snow sports. More detailed weather information is given below, but a far bigger factor in your planning should be avoiding major Korean holidays. Domestic tourists take to the roads in the tens of thousands, crowding all forms of transportation, filling hotels, and making it difficult to visit popular attractions. By contrast, Seoul empties out and traffic is almost nonexistent. For the latest news and more detail check out the Korea Tourism Organization (KTO) at http://english.visitkorea.or.kr.

Peak Travel Times

Seol (Lunar New Year) Although January 1 is also celebrated in South Korea, Seol (also known as Seollal) is a bigger holiday. It can be difficult for tourists to figure out when the Lunar New Year will fall, as Westerners rely on a solar calendar. The solar calendar equivalents of the Lunar New Year for the next few years are February 10, 2013; January 31, 2014; February 19, 2015; February 8, 2016. Most Koreans get 3 days off during the holiday and use that time to travel to their hometown. Others take the opportunity to go on ski holidays or travel abroad. Bus and train tickets go on sale 3 months beforehand and people line up for hours in order to get their passage out of town. Driving is a bad option, since the normal 5- to 6-hour drive from Seoul to Busan, for example, can take up to 14 hours due to ridiculous traffic.

Children’s Day Though not necessarily in prime travel season, May 5 is the day South Koreans celebrate their little ones. Parents dress up their kids and take them to amusement parks, zoos, theaters—pretty much anywhere children love to go. If you want to avoid big crowds, stay away from kiddie hot spots on this day.

Summer Holidays It’s not as insanely busy as the Lunar New Year or Chuseok (see below), but when the kids go on summer break, many families head out of Seoul to take a trip to the beaches or the mountains. Korean children have only about 6 weeks of summer break, usually from mid-July to late August, but university students keep trains and buses busy throughout the season. Be sure to book rooms in popular destinations (such as Busan’s beaches, which get super-crowded June–Aug) well in advance.

Chuseok (Harvest Moon Festival) Another traditional holiday as important as Lunar New Year, Chuseok (sometimes spelled Chusok) is celebrated on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month, usually sometime in mid- to late September. Solar equivalents for the next few years are September 19, 2013; September 8, 2014; September 27, 2015; and September 15, 2016. The days before and after are considered legal holidays in South Korea. Once again, Korean families mobilize to visit their hometowns and pay respect to their ancestors. Tickets for travel usually sell out 3 months in advance and roads and hotels are packed.

Weather

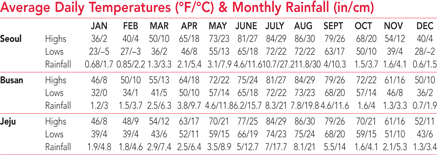

South Korea’s climate can be described as temperate, with four distinct seasons. The weather is heavily influenced by the oceans that surround the Korean Peninsula and by its proximity to the rest of Asia to the north. Winters and summers are long and punctuated by short but enjoyable springs and autumns.

Winter begins in November as cold air moves south from Siberia and Manchuria. By December and January, average temperatures drop below 32°F (0°C) over the whole country, with the notable exception of Jeju-do and some coastal areas. In Seoul, winter temperatures usually drop to 18°F (–8°C) and have been known to fall to –11°F (–24°C).

Spring starts by the end of March, when warm air begins to move north off the Pacific Ocean. Temperatures usually average 51°F (11°C), and rainfall is unpredictable. By the end of May, summer brings a period of warmth and humidity with heavy rainfall that starts in July and lasts until the end of September. Summer temperatures average 77°F (25°C), but often approach 86°F (30°C) in July and August. It’s not the heat that’s the challenge; it’s the humidity. South Korea gets about 125cm (49 in.) of rain annually, 60% of which falls during the summer months. In general, the southern and western regions see more rain, with Jeju-do having the highest average rainfall per year. The summer is also typhoon season in South Korea. Although most typhoons lose their strength by the time they make it to the peninsula, some cause flooding, structural damage, and, in extreme cases, even death.

By late September, the cool, dry winds from Siberia change the weather again. Temperatures fall to about 59°F (15°C) and skies generally remain clear and crisp, with very little rainfall. Koreans consider autumn the best season, marked by the most important national holiday, Chuseok, when people visit their ancestral homes and give thanks for the harvest. Trees throughout the country exchange their summer greens for fall (autumn) colors and Koreans flock to the mountains in droves to see nature’s show.

Public Holidays

South Koreans celebrate both holidays from the traditional lunar calendar (see above) and holidays adopted from the Western calendar. National public holidays are New Year’s Day (celebrated Jan 1 and 2), Lunar New Year’s Day (usually in Jan or Feb, and the 2 days following it—see “Peak Travel Times,” above, for exact dates), Independence Movement Day (Mar 1), Arbor Day (Apr 5), Children’s Day (May 5), Buddha’s Birthday/Feast of the Lanterns (the eighth day of the fourth lunar month, usually in Apr or May), Memorial Day (June 5), Constitution Day (July 17), Liberation Day (Aug 15), Foundation Day (Oct 3), Harvest Moon Festival (14th–16th days of the eighth lunar month—see “Peak Travel Times,” above, for exact dates), and Christmas Day (Dec 25).

Calendar of Events

South Korea’s traditional festivals follow the lunar calendar, but modern festivals follow the solar/Gregorian calendar. For conversion to solar calendar dates, visit www.mandarintools.com/calconv_old.html or www.chinesefortunecalendar.com/CLunarCal1.htm.

With festivals for everything from fireflies and pine mushrooms to swimming in icy-cold water, Koreans will most likely be celebrating something when you visit. Regional festivals are a great way to get a sense of just how varied Korean culture is while experiencing traditional costumes, performances, and music.

For an exhaustive list of events beyond those listed here, check http://events.frommers.com, where you’ll find a searchable, up-to-the-minute roster of what’s happening in cities all over the world.

January

Seol (Lunar New Year) is still one of the biggest holidays of the year. Koreans get up early, put on their best clothes (usually the traditional hanbok), and bow to their elders. Families celebrate with feasts of dduk guk (rice-cake soup) or mandu guk (dumpling soup), and the palaces in Seoul host special events. See “Peak Travel Times,” above, for dates.

Hwacheon Mountain Trout Festival ( 033/441-7575) is a charming festival celebrating the mountain trout (the “Queen of the Valleys”). Thousands of people descend upon this small town in Gangwon-do (see chapter 10) to catch this fish and enjoy a variety of winter sports. Through most of January.

033/441-7575) is a charming festival celebrating the mountain trout (the “Queen of the Valleys”). Thousands of people descend upon this small town in Gangwon-do (see chapter 10) to catch this fish and enjoy a variety of winter sports. Through most of January.

February

Inje Ice Fishing Festival ( 033/460-2082) occurs every winter, when Soyang Lake freezes over and hundreds of people flock to this mountain village in the inner Seoraksan area. Not only will you be able to ice fish, but you also can play ice soccer (football), go sledding, watch a dog sled competition, and enjoy a meal of freshly caught smelt. Late January through mid-February.

033/460-2082) occurs every winter, when Soyang Lake freezes over and hundreds of people flock to this mountain village in the inner Seoraksan area. Not only will you be able to ice fish, but you also can play ice soccer (football), go sledding, watch a dog sled competition, and enjoy a meal of freshly caught smelt. Late January through mid-February.

March

Jeongwol Daeboreum Fire Festival celebrates the first full moon of the lunar year. The celebrations involve both livestock—there are duck and pig races—and nods to the island’s history. The festival arose from the island’s ancient practice of burning grazing fields, which served the dual purpose of razing the land for new crops and getting rid of pests. Don’t miss the spectacular fireworks show. February or March on the 15th day of the first lunar month.

Gyeongju Traditional Drink & Rice Cake Festival ( 054/748-7721 or 2; www.fgf.or.kr) is held at Hwangseong Park in Gyeongju every March or April (dates vary wildly, so be sure to check ahead of time) and is the perfect place to sample everything from rice cakes to rice wine. You can also try your hand at pounding rice into cakes the old-fashioned way (with a wooden mallet), see traditional folk performers, and enjoy the market-like atmosphere.

054/748-7721 or 2; www.fgf.or.kr) is held at Hwangseong Park in Gyeongju every March or April (dates vary wildly, so be sure to check ahead of time) and is the perfect place to sample everything from rice cakes to rice wine. You can also try your hand at pounding rice into cakes the old-fashioned way (with a wooden mallet), see traditional folk performers, and enjoy the market-like atmosphere.

April

Gwangalli Eobang Festival ( 051/610-4062, ext. 4) celebrates the arrival of spring and was founded in 2001, when three smaller festivals were combined. The festivities are kicked off when hundreds of Busan residents parade in masks and costumes. The costumes are a mix of old and new, and represent a traditional play called “Suyeong Yaryu,” which originated from Suyeong-gu (an area in central Busan) and which mocks the yangban (noble class). Other events include the local custom of praying for the safe return of fishermen (with a big catch, of course). At night, you can enjoy the fireworks and the lights of the Jindu-eoha, where fishing boats are lit to re-enact traditional torchlight fishing. Early April.

051/610-4062, ext. 4) celebrates the arrival of spring and was founded in 2001, when three smaller festivals were combined. The festivities are kicked off when hundreds of Busan residents parade in masks and costumes. The costumes are a mix of old and new, and represent a traditional play called “Suyeong Yaryu,” which originated from Suyeong-gu (an area in central Busan) and which mocks the yangban (noble class). Other events include the local custom of praying for the safe return of fishermen (with a big catch, of course). At night, you can enjoy the fireworks and the lights of the Jindu-eoha, where fishing boats are lit to re-enact traditional torchlight fishing. Early April.

Jeonju International Film Festival (www.jiff.or.kr) is held in (where else?) Jeonju (see chapter 8). You won’t catch many blockbusters here—the festival is more focused on short independent films—but you may discover a new star on the rise. Late April to early May.

Hi Seoul Festival ( 02/3290-7150; www.hiseoulfest.org) highlights the history and culture of South Korea’s capital. Most of this festival’s events, including everything from classical music to rock music concerts, happen in the downtown area. Don’t miss the spectacular lighted boat parade in the evenings in Yeoui-do. Lasts about a week, usually in early May.

02/3290-7150; www.hiseoulfest.org) highlights the history and culture of South Korea’s capital. Most of this festival’s events, including everything from classical music to rock music concerts, happen in the downtown area. Don’t miss the spectacular lighted boat parade in the evenings in Yeoui-do. Lasts about a week, usually in early May.

Icheon Ceramic Festival ( 031/644-2944, ext. 4) Want to experience the history and craftsmanship of Korean pottery? Then head to Icheon (see chapter 6) for this festival, where you can even buy handmade ceramics from the artists themselves. Late April.

031/644-2944, ext. 4) Want to experience the history and craftsmanship of Korean pottery? Then head to Icheon (see chapter 6) for this festival, where you can even buy handmade ceramics from the artists themselves. Late April.

May

Boseong Green Tea (Da Hyang) Festival ( 061/852-1330; www.boseong.go.kr) is held in South Korea’s most important tea-producing region. Enjoy Jeollanam-do (see chapter 7) and taste some of the finest nokcha (green tea) in the world, fresh from the plantation. You can also try foods made with green tea, try a tea facial, and participate in traditional tea ceremonies. Early May, in odd-numbered years (2013, 2015, and so on).

061/852-1330; www.boseong.go.kr) is held in South Korea’s most important tea-producing region. Enjoy Jeollanam-do (see chapter 7) and taste some of the finest nokcha (green tea) in the world, fresh from the plantation. You can also try foods made with green tea, try a tea facial, and participate in traditional tea ceremonies. Early May, in odd-numbered years (2013, 2015, and so on).

Lotus Lantern Festival ( 02/2011-1744, ext. 7; www.llf.or.kr) coincides with Buddha’s Birthday (also known as “The Day the Buddha Came”), and it is not to be missed. Hundreds of thousands of people parade along the Han River with lanterns. The opening ceremony for the parade starts at Dongdaemun Stadium. Other events happen in temples throughout the country in mid-May.

02/2011-1744, ext. 7; www.llf.or.kr) coincides with Buddha’s Birthday (also known as “The Day the Buddha Came”), and it is not to be missed. Hundreds of thousands of people parade along the Han River with lanterns. The opening ceremony for the parade starts at Dongdaemun Stadium. Other events happen in temples throughout the country in mid-May.

Gangneung Danoje Festival (http://english.visitkorea.or.kr/enu/SI/SI_EN_3_2_1.jsp?cid=293063) celebrates Dano (the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar year) with brewing of sacred wine. Although there are month-long events, the main festivities happen in the 3 to 4 days surrounding Dano. Highlights include the Gwanno mask drama—a pantomime combining Korea’s ancient shamanistic beliefs with traditional dance and mask play that was performed and handed down by government servants during the Joseon Dynasty—and daily shamanistic rituals. The festivities have been deemed an important, intangible cultural property by UNESCO. Late May through June in Gangwon-do.

June

Muju Firefly Festival ( 063/322-1330; festival@firefly.or.kr) honors the local ecosystem. This is the only place in South Korea where fireflies are found, and the people of Muju use the insect’s annual appearance as an excuse to celebrate. The festival also includes taekwondo demonstrations, since Muju is the site of the World Taekwondo Park. Early June in Jeollabuk-do.

063/322-1330; festival@firefly.or.kr) honors the local ecosystem. This is the only place in South Korea where fireflies are found, and the people of Muju use the insect’s annual appearance as an excuse to celebrate. The festival also includes taekwondo demonstrations, since Muju is the site of the World Taekwondo Park. Early June in Jeollabuk-do.

July

Boryeong Mud Festival ( 011/438-4865; www.mudfestival.or.kr) is all about rolling around in the mud. Supposedly very good for your skin, mud from this region is used in cosmetics and massages. Great fun for kids, events include mud wrestling, mud slides, and making mud soap. For one week in mid-July in Chungcheongnam-do (see chapter 6).

011/438-4865; www.mudfestival.or.kr) is all about rolling around in the mud. Supposedly very good for your skin, mud from this region is used in cosmetics and massages. Great fun for kids, events include mud wrestling, mud slides, and making mud soap. For one week in mid-July in Chungcheongnam-do (see chapter 6).

August

Busan International Rock Festival (www.rockfestival.co.kr) turns Dadaepo Beach into an open-air concert venue. This free festival attracts over 150,000 fans to see musicians from South Korea and all over the world. Early August.

Muan White Lotus Festival (http://tour.muan.go.kr) is held at Asia’s largest field of the rare white lotus. Other than walking through the gardens, you can take a boat ride to see the blooms up close, enjoy contemporary and traditional performances, and eat a variety of foods made from lotuses. Try the lotus ice cream and the lotus noodles. Mid-August in Muan-geun in Jeollanam-do.

September

Chuseok (Harvest Festival) is another important traditional holiday and is held on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. Also called Korean Thanksgiving, this holiday celebrates the bountiful harvest and hopes for another good year to come. Although most Koreans will be traveling to their ancestral homes, festivities are held at the palaces and at the National Folk Museum in Seoul. See “Peak Travel Times” to see dates for the next few years. Usually sometime in September.

October

Busan International Film Festival (BIFF; www.biff.kr) is one of the largest showcases for new films in Asia. The festival attracts over 200 films from dozens of different countries (with an emphasis on Asian films, of course). Usually happens in mid-October.

Jagalchi Festival ( 051/243-9363; www.ijagalchi.co.kr) is South Korea’s largest seafood festival. Celebrating the sea, traditional fishing rituals are performed and you can enjoy raw fish and discounts on pretty much everything that’s sold at the Jagalchi Market. Mid-October in Busan.

051/243-9363; www.ijagalchi.co.kr) is South Korea’s largest seafood festival. Celebrating the sea, traditional fishing rituals are performed and you can enjoy raw fish and discounts on pretty much everything that’s sold at the Jagalchi Market. Mid-October in Busan.

Icheon Rice Cultural Festival ( 031/644-4121; www.ricefestival.or.kr) celebrates the agriculture (particularly rice) from the plains of Icheon, which once grew the rice served to royalty. Held at Icheon Seolbong Park; stop in at a neighborhood restaurant for rice and vegetables in a dolsotbap (hot stone pot). Late October.

031/644-4121; www.ricefestival.or.kr) celebrates the agriculture (particularly rice) from the plains of Icheon, which once grew the rice served to royalty. Held at Icheon Seolbong Park; stop in at a neighborhood restaurant for rice and vegetables in a dolsotbap (hot stone pot). Late October.

November

Gwangju World Kimchi Culture Festival ( 062/613-3641 or 2; http://kimchi.gwangju.go.kr) highlights this 5,000-year-old Korean food tradition. Taste the variety of the region’s kimchi (the most popular type being made from fermented napa cabbage), or make some of your own. Mid-November.

062/613-3641 or 2; http://kimchi.gwangju.go.kr) highlights this 5,000-year-old Korean food tradition. Taste the variety of the region’s kimchi (the most popular type being made from fermented napa cabbage), or make some of your own. Mid-November.

Natural World

Located on the southern half of the Korean Peninsula, South Korea is surrounded mostly by ocean—nearly 1,500 miles (2,413 km) of coastline—spanning the Yellow Sea to the west, the East China Sea to the south, and the East Sea (Sea of Japan) to the east. South Korea is separated from North Korea by the DMZ, the world’s most heavily guarded border, which runs about 148 miles (238 km), just north of the 38th parallel. Although the country’s land mass is not large (only about 38,623 sq miles, 100,032 sq km), the country is crisscrossed by a number of mountain ranges, leaving just a small percentage of the land available for farming. The highest mountain in South Korea is Hallasan, which is on the country’s largest island, Jeju-do, located to the southwest of the peninsula.

The country has 9 provinces. Gangwon-do, located in the northeast, borders the DMZ and is the most mountainous. Gyeonggi-do surrounds Seoul and also borders the DMZ. Chungcheongnam-do is located to the south of Gyeonggi-do. Its neighbor, Chungcheongbuk-do is the only land-locked province in the country. To the east of Chungcheongbuk-do lies Gyeongsangbuk-do, which includes the historic towns of Andong and Gyeongju. To the south is Gyeongsangnam-do, which includes the city of Busan and several islands. Jeollanam-do to the west is also a coast-heavy province with nearly 2,000 islands off its coast, the majority of which are uninhabited. Its neighbor, Jeollabuk-do includes Jeonju and more mountainous regions. Jeju-do is South Korea’s ninth province.

Responsible Travel

Although South Korea is not particularly eco-friendly, the nation has been making more effort toward green living. Cities now have recycling (city dwellers are required to sort their waste) and buses with reduced emissions.

National and municipal governments have launched several efforts to make South Korea more environmentally conscious. Programs like the preservation of wetlands in places like Upon-eup , Junam, and Suncheon-man provide sanctuary for migrating birds as well as maintaining natural environments friendly to other wildlife. Unfortunately, the more they create awareness of certain areas, the more people come to visit, making it not so friendly for the birds and other animals there.

The good thing about South Korea is the country’s extensive national park system (http://english.knps.or.kr). The government-run organization maintains the scenic mountains and the fragile environments of its islands and coastal locations as well.

In Seoul, Gyeongju, and other cities, the government has launched a bicycle program, building more trails and providing a standardized bike-rental scheme. See the “By Bicycle” section under “Getting Around,” in the planning chapter.

Another form of eco-tourism the Koreans are trying out is hands-on experiences and tours of organic farms throughout the country. We’ve highlighted some options in the following regional chapters.

Although South Korea has no organized dolphin or whale-watching opportunities, 41 different species of these marine mammals can be found off the coasts of the peninsula. For information about the ethics of swimming with dolphins and other outdoor activities, visit the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (www.wdcs.org) and Tread Lightly (www.treadlightly.org).

In addition to the resources for South Korea listed above, see www.frommers.com/planning for more tips on responsible travel.

Tours

Since South Korea is still a mystery to most travelers, there aren’t that many specialized tours offered. However, some do show off specific areas of the country’s cultural kaleidoscope.

Aju Incentive Tours (www.ajutours.co.kr) has a 6-day culinary tour of Seoul, which includes a cooking class, an opportunity to sample temple fare, and a cultural performance. They also offer a 4-day Oriental health tour exploring different aspects of traditional medicine, including a sauna, foot massages, and a visit to the traditional herbal market. Their other tours highlight different aspects of South Korea’s arts and culture or explore the country’s historical religions; they also offer ski tours, and even a bird-watching tour. Although bird-watching is a relatively new hobby in the country, Birds Korea (www.birdskorea.org) offers guided tours to see migrating fowl and birds unique to the region.

The KTO ( 02/729-9497, ext. 499, or the 24-hr. travel info hot line

02/729-9497, ext. 499, or the 24-hr. travel info hot line  1330; http://english.tour2korea.com) will help you arrange seasonal and themed tours to specialized regions in the country.

1330; http://english.tour2korea.com) will help you arrange seasonal and themed tours to specialized regions in the country.

Tours from South Korea into North Korea are closed for the moment (after an unfortunate incident in which a South Korean housewife was shot and killed by a North Korean soldier). The closest you can get is to the Panmunjeom at the DMZ, which you can access via a day tour from Seoul. Plan your trip at least 3 days in advance. See chapter 4 for detailed information on various trip options.

Many of the major cities in South Korea also offer city tours. You can tour Seoul, Busan, Gyeongju, Daegu, Daejeon, Incheon, Suwon, Gongju, and Ulsan by bus. See each of these city’s specific sections or chapters for additional information.

Academic Trips & Language Classes

Many major universities in Seoul (as well as a few in Busan, Daejeon, Busan, and other cities) offer semester- or quarter-long language programs for learning the basics of Korean. The most popular programs are, of course, during the summer months, but classes are available year-round. Ewha Women’s University ( 02/3277-3683; http://ile.ewha.ac.kr) has 10-week and intensive 3-week courses. Yonsei University (

02/3277-3683; http://ile.ewha.ac.kr) has 10-week and intensive 3-week courses. Yonsei University ( 02/2123-3464; www.yskli.com) has a popular summer language program. Seoul National University (

02/2123-3464; www.yskli.com) has a popular summer language program. Seoul National University ( 02/880-8570; http://lei.snu.ac.kr/site/en/klec/main/main.jsp) provides a 5-week summer program, but has classes year-round. Korea (Goryeo) University (

02/880-8570; http://lei.snu.ac.kr/site/en/klec/main/main.jsp) provides a 5-week summer program, but has classes year-round. Korea (Goryeo) University ( 02/3290-2971 or 2972; http://klcc.korea.ac.kr/main.mainList.action?langDiv=2) has quarterly language programs.

02/3290-2971 or 2972; http://klcc.korea.ac.kr/main.mainList.action?langDiv=2) has quarterly language programs.

Sogang University ( 02/705-8088; http://klec.sogang.ac.kr/root/index.php?lang=english) offers a “master class,” a 6-week workshop where well-known Korean artists, filmmakers, writers, or musicians provide insight from their experiences in their particular field of expertise. You can also enroll in their regular 10-week language courses year-round.

02/705-8088; http://klec.sogang.ac.kr/root/index.php?lang=english) offers a “master class,” a 6-week workshop where well-known Korean artists, filmmakers, writers, or musicians provide insight from their experiences in their particular field of expertise. You can also enroll in their regular 10-week language courses year-round.

Adventure & Wellness Trips

Adventure Korea ( 018/242-5536; www.adventurekorea.com) offers a variety of active tours around the country, based on the season. Choose from active trips, such as snowboarding in Pyeongchang, ice fishing for trout in Hwacheon, or rockclimbing Songnisan. You can also have them customize a tour for you, if you can round up 19 of your friends. Adventure Travelers (

018/242-5536; www.adventurekorea.com) offers a variety of active tours around the country, based on the season. Choose from active trips, such as snowboarding in Pyeongchang, ice fishing for trout in Hwacheon, or rockclimbing Songnisan. You can also have them customize a tour for you, if you can round up 19 of your friends. Adventure Travelers ( 630/915-5618 from U.S.; www.adventure-travelers.com) offers specialty tours of South Korea, including a week of taekwondo training, a 2-week trip with hands-on ceramics, and trips focusing on watersports or skiing. One of the best tours from an Australian operator is by The Imaginative Traveller (

630/915-5618 from U.S.; www.adventure-travelers.com) offers specialty tours of South Korea, including a week of taekwondo training, a 2-week trip with hands-on ceramics, and trips focusing on watersports or skiing. One of the best tours from an Australian operator is by The Imaginative Traveller ( 1300-135-088; www.imaginative-traveller.com), which provides a 15-day “adventure” tour that hits the major destinations as well as Seoraksan and the caves in Samcheok.

1300-135-088; www.imaginative-traveller.com), which provides a 15-day “adventure” tour that hits the major destinations as well as Seoraksan and the caves in Samcheok.

Food & Wine Trips

Unfortunately, no tour company offers regular culinary tours in South Korea. However, special tour packages are offered from time to time, usually in conjunction with a special event. In Seoul, O’ngo Food Communications ( 02/3446-1607; www.ongofood.com) offers the best tours, including their “Korea Taste Tour,” a 2.5-hour walking survey that includes tastings from street stalls and restaurants, starting at ₩57,000 per person. They also have regular cooking classes Monday–Friday at 10am and 2pm (also on Saturday, by request), which start at ₩65,000 per person and include a visit to a traditional market.

02/3446-1607; www.ongofood.com) offers the best tours, including their “Korea Taste Tour,” a 2.5-hour walking survey that includes tastings from street stalls and restaurants, starting at ₩57,000 per person. They also have regular cooking classes Monday–Friday at 10am and 2pm (also on Saturday, by request), which start at ₩65,000 per person and include a visit to a traditional market.

Traditional food classes are offered at the Institute of Traditional Korean Food at the Tteok Museum ( 02/741-5447; www.kfr.or.kr/eng/index.htm). For ₩70,000, you can choose two dishes to cook from a list of traditional recipes. They require a minimum of two people and reservations at least a week in advance. There are no programs on Sunday.

02/741-5447; www.kfr.or.kr/eng/index.htm). For ₩70,000, you can choose two dishes to cook from a list of traditional recipes. They require a minimum of two people and reservations at least a week in advance. There are no programs on Sunday.

Volunteer & Working Trips

Habitat for Humanity ( 02/2267-3702, ext. 402; http://www.habitat.or.kr/eng_new/index.asp) has special volunteer trips to help build homes for poor South Koreans, from May through early November. No special skills are required, just a willingness to learn and roll up your sleeves. Check their website for volunteer trips and opportunities.

02/2267-3702, ext. 402; http://www.habitat.or.kr/eng_new/index.asp) has special volunteer trips to help build homes for poor South Koreans, from May through early November. No special skills are required, just a willingness to learn and roll up your sleeves. Check their website for volunteer trips and opportunities.

CADIP (the Canadian Alliance for Development Initiatives and Projects; www.cadip.org) has several volunteer opportunities working with schoolchildren in areas like Muju, Jangheung, Namwon, or Samcheok. Most of their programs cost Canadian $590 (about US$470) plus an additional US$260 (approximately) for the hosting organization, but this covers shared accommodations and three meals daily. Visit their website for details and to apply.

United Planet ( 800/292-2316 in the U.S.; www.unitedplanet.org) offers 6-month and 1-year volunteer programs that start in January and August. The program starts at US$6,065 per person, and includes training, food, lodging, monthly stipends, and emergency medical insurance. Airfare, vaccinations, visa costs, and travel to the pre-departure training site are not included.

800/292-2316 in the U.S.; www.unitedplanet.org) offers 6-month and 1-year volunteer programs that start in January and August. The program starts at US$6,065 per person, and includes training, food, lodging, monthly stipends, and emergency medical insurance. Airfare, vaccinations, visa costs, and travel to the pre-departure training site are not included.

Special-Interest Trips

If you’ve found yourself engrossed in the latest Korean drama offering, tissue in hand, yelling at the screen, you may want to tear yourself away to see some of the locations in person. Happy Mize ( 070/8627-8080; www.happymize.com) offers a 5-day/4-night tour, which costs ₩1,630 per person for two people, or ₩830 per person if 21+ people are on the tour. The price includes transportation, hotel, all admission fees, meals, and an English-speaking guide.

070/8627-8080; www.happymize.com) offers a 5-day/4-night tour, which costs ₩1,630 per person for two people, or ₩830 per person if 21+ people are on the tour. The price includes transportation, hotel, all admission fees, meals, and an English-speaking guide.

Grace Travel ( 02/332-8946; http://english.triptokorea.com) has a variety of tours including a pottery tour of Icheon, which includes the Leeum Samsung Museum. The tour from Seoul starts at 9am and costs ₩138,000 per person (minimum 3 people) or ₩10,000 more for two people. They also have a 2-day tour to Cheonghakdong that includes lessons in traditional Korean etiquette, a guided tour to Buyeo and Gongju, and a ski-tour that includes a dip in the hot springs in Yeongpyeong.

02/332-8946; http://english.triptokorea.com) has a variety of tours including a pottery tour of Icheon, which includes the Leeum Samsung Museum. The tour from Seoul starts at 9am and costs ₩138,000 per person (minimum 3 people) or ₩10,000 more for two people. They also have a 2-day tour to Cheonghakdong that includes lessons in traditional Korean etiquette, a guided tour to Buyeo and Gongju, and a ski-tour that includes a dip in the hot springs in Yeongpyeong.

Escorted General-Interest Tours

Escorted tours are structured group tours, with a group leader. The price usually is all-inclusive, although some of the tours listed here do not include airfare to and from South Korea.

If you’re interested in rail travel, KoRail Tourism Development ( 02/2084-7744; www.korailtravel.com) offers rail-based tours including one to Jeongseon, that includes a ride on the rail bikes (2- or 4-person vehicles that you peddle on the train tracks) and the “Korean Wave Express” that rolls out every Saturday and Sunday from Seoul.

02/2084-7744; www.korailtravel.com) offers rail-based tours including one to Jeongseon, that includes a ride on the rail bikes (2- or 4-person vehicles that you peddle on the train tracks) and the “Korean Wave Express” that rolls out every Saturday and Sunday from Seoul.

All4uKorea (http://ggmland.com/tour/indexenglish.html) is a group of tour operators based out of Seoul that offer customized tours with private drivers. You can also contact them about designing your own tour. Root Travel Ltd. ( 02/542-8606; www.roottravel.co.kr), also based out of Seoul, provides 2- to 16-day general tours spanning Seoul to the rest of South Korea.

02/542-8606; www.roottravel.co.kr), also based out of Seoul, provides 2- to 16-day general tours spanning Seoul to the rest of South Korea.

Sky Tour ( 02/711-0204; www.traveltokorea.co.kr) has a variety of tours including a 7-day “best of” tour that includes Seoul, Yongjin, Gyeongju, Busan, and Jeju that starts at US$1,200 per person. Tour East Holidays (

02/711-0204; www.traveltokorea.co.kr) has a variety of tours including a 7-day “best of” tour that includes Seoul, Yongjin, Gyeongju, Busan, and Jeju that starts at US$1,200 per person. Tour East Holidays ( 416/929-6688 from Canada; www.toureastholidays.com), a Toronto-based company, offers a brief South Korea tour that hits the three major cities. R&C Hawaii Tours (

416/929-6688 from Canada; www.toureastholidays.com), a Toronto-based company, offers a brief South Korea tour that hits the three major cities. R&C Hawaii Tours ( 808/942-3388; www.rchawaii.com) offers both escorted and non-escorted packages. A.T. Seasons & Vacations Travel (

808/942-3388; www.rchawaii.com) offers both escorted and non-escorted packages. A.T. Seasons & Vacations Travel ( 91-11-22794796; www.visitsasia.com), based in New Delhi, offers 4- to 7-day general tours of South Korea, starting from Incheon airport. The KTO (http://english.visitkorea.or.kr) also provides tours that are coming up and a list of travel agencies in your home country that can arrange escorted tours to fit your needs.

91-11-22794796; www.visitsasia.com), based in New Delhi, offers 4- to 7-day general tours of South Korea, starting from Incheon airport. The KTO (http://english.visitkorea.or.kr) also provides tours that are coming up and a list of travel agencies in your home country that can arrange escorted tours to fit your needs.

For more information on escorted general-interest tours, including questions to ask before booking your trip, see www.frommers.com/planning.

Walking Tours

The Seoul government offers several walking tours of the city free of charge. See “Walking Tours” in chapter 4 for more info.