Growing up I was taught the conventional method of gardening. It is a good method with a proven track record. But when I started my own garden I began to question everything that I had been taught. No gardening procedure was accepted as the “correct way,” it was only accepted as “one way.” Was there a better way? One could find out only by looking for alternatives.

To seek answers I began researching all aspects of what is involved in the growing of plants. Besides studying advanced fundamentals, I was particularly interested in learning more about some of the unconventional systems that were being practiced. Nothing was considered too weird or bizarre; everything was given serious thought and, if at all possible, tried.

This probing, which involved extensive research, analysis and experimentation, in most cases, resulted in my coming right back full circle to the old tried and true ways. Nevertheless, now and then, some worthwhile variations were come across and slowly over the years my gardening approach did undergo certain changes.

The thought processes that reshaped my perception of gardening along with their results are presented here.

Generally when something is very complicated the tendency is to analyze then simplify: Most of the time this is a good idea. But, with the growing of plants simpler is not always better. In nature complexity is essential to maintain stability. Simple systems are very erratic. In regions where there are few species of insects and plants there will be severe changeability.

If, for instance, insect “A” has only a single predator, if that one stops reproducing there will not be anything to keep insect “A” in check. It will soon multiply wildly. In a complex ecosystem there are many predators for any one insect. If one predator is eliminated, nothing drastic changes because the others are still there to maintain the balance—natural pest control.

Just as a diversity of insects ensures stability so does a complex plant population. A bug that eats one plant may not eat any other. A diversified planting in itself acts as a natural check. What’s more, the plants which that bug does not eat may be the place where his predators go to breed, as different plants appeal to different insects. Complexity is desirable, don’t try to figure out all of the workings of nature, just accept it.

If you take time to observe, you will notice many instances of why the complex ecosystem is best. I have found that gardening is less stressful and more successful if one makes the effort to learn from, and cooperate with Mother Nature.

In nature there is always a variety of plants growing side by side. It is not natural for just one species to grow over a large area all by itself. If this begins to happen, a disease, a swarm of locusts, or something else will develop to devastate the plants and restore the balance.

This principle can, and should be applied as a cultural control in your home garden. Monoculture should be avoided: As in nature, create diversity. There should always be a variety of vegetables growing in close proximity to each other. This will lessen the chances of disease or insect problems.

As for weeds in the garden, they are simply plants trying to reclaim their own territory. They have a right to be there, and are helpful and beneficial up to a point. They are much stronger than the garden plants and will come up first, breaking the soil and helping to keep it from crusting. Don’t be too quick to pull them, let them help you first!

Just as I understand the right of weeds to grow, I am also aware that insects have the right to exist. They are an important part of nature, each contributing something and each having a natural enemy. In other words, unless the balance of nature is upset, they usually are not a great problem. It is not possible or desirable to completely eliminate all bugs from a garden. The goal should not be eradication, it should be control.

The first control is to grow healthy plants. Vigorous plants will not be bothered much by bugs.

The second control is not to grow plants that seem to attract an unusual amount of insects. For some reason perhaps that plant is not suited to your area or to your soil.

The third control is garden hygiene. Bugs are attracted by rotting vegetation or dying plants. Keep the garden clean, pick up any fallen leaves, fruit or other debris. Remove any diseased or dying plants promptly.

The fourth control is to avoid monoculture. It is nature’s way and it does work. An inordinate amount of harmful insects are not attracted to mixed plantings.

As for soil, it has been my observation that nature does not tolerate bare earth. Something must either be growing on it or covering it at all times. If a patch of ground is suddenly exposed by an unusual occurrence, very quickly some type of plant life will start to grow there. Aside from any abnormal circumstance, in nature the soil remains intact from season to season; there is no disruption in its structure equivalent to the gardener turning the soil every year.

While the digging up of the ground is necessary in the establishment of a new garden, once the soil is in good tilth it does more harm than good. In the fall nature covers the ground with falling leaves and other decaying material. Following that lead, at the end of the growing season, in preparation for winter, I cover the bare ground with a mulch of leaves. Mother Nature does not dig up the earth every year, so now, neither do I. After all, Mother knows best!

Having said all that, it must always be kept in mind that a vegetable garden is an introduction of alien plants, an upsetting of the natural balance in that plot of ground. Nature will continually try to eradicate it.

Therefore, on some occasions, the gardener will be compelled to fight nature, while in other instances it is better to let her have her way. It is a delicate balancing act.

As for soil management, there is no question that her methods are best. Improve the soil using only organic methods: Absolutely no pesticides, no artificial fertilizers or chemicals of any kind.

In the case of insect control one can go along to a certain extent. However, complete reliance on nature in this area is not practical as there will always be times when the natural enemies of a bug that is chewing on your crops are either out of town or otherwise occupied. On such occasions you are the only natural enemy of this bug available. At other times there may be an unusual influx of a particular type of insect. Again, you cannot sit idly by; you must act to bring the situation under control: The key word being “control,” not necessarily total annihilation.

As for weeds, again, nature cannot be allowed to dominate completely, accept them as long as they are serving a beneficial purpose, beyond that point they have to be eliminated.

We must always be aware that we are presiding over an altered environment; nature’s ways will have to be slightly modified to be compatible. In the real world we have to face realities, and the reality is that one cannot grow vegetables successfully simply by letting nature take its course. The time-tested methods of conventional gardening cannot be dismissed lightly, they still have an important role in gardening.

All things considered, I have reached the conclusion that a combining of natural methods with conventional methods is the logical road to take. It is the road that I have chosen and have been rewarded with gratifying results.

When we establish a home garden we are, basically, in the business of growing vegetables. Whether the produce is sold or not, is irrelevant, something of monetary worth is being produced. To be a feasible venture, total value of vegetables produced must be more than total expenses. If a garden is viewed from that perspective, it is obvious that costs must be kept to an absolute minimum.

As in a new commercial enterprise a written “business plan” is a big help in creating a no-nonsense vegetable garden. The benefit of such a plan is that by putting it down on paper you can see the whole picture.

It also forces one to think things through making it less likely to overlook something very important.

The “business plan” for establishing my garden was a clear specific listing of goals. Once those had been set, then I could concentrate on the exact size, configuration, and method of working the garden. During that phase, there were many mistakes and detours. I constantly had to refer back to my recorded objectives to get back on track.

Many seasons went by before I was able to integrate organic growing methods and my modular system into an effective unit. This combination meets all of the economic requirements as it is efficient, productive, and cheap.

To establish a three-module home vegetable garden there are certain unavoidable start-up costs; basic tools, watering devices, and the materials for making all of the modular components must be bought. But, these are usually only one-time expenses, most of these items if properly cared for will last a lifetime.

Beyond those initial expenditures, through the use of organic growing methods, year to year expenses are very low. Compost is made at no cost, no outlay of cash is needed for leaf mulches, and earthworms work for nothing.

Practicing frugality in gardening simply makes good common sense. Unnecessary expenditures are never justified: The less your costs, the greater the value of the produce.

My search for a better way of growing vegetables which, among other things, led to the development of my modular gardening system was a long but fulfilling journey.

The first step of this endeavor came about, when due to the requirements of a growing family, I bought a modest house that had a small backyard. Although just about everyone else on the block was concerned about having a perfect front lawn, it was the area in the back of the house that aroused my interest. I hadn’t done any gardening since my teens. But looking back there my mind visualized row after row of vegetables.

I began to take note of the patterns of sunshine and shade to determine the best place to start a garden. It wasn’t long before that became apparent. A spot a few feet from the garage wall received sun most of the day and the sun’s rays bouncing off the concrete block wall warmed up that area earlier in the spring.

Size was a key factor. Enough room had to be left for other activities and, being employed in a full time job, ongoing upkeep was a big consideration. It had to be fairly small. But still, it was unthinkable to have a make-believe garden, just something as a part time hobby to putter around in. If I was going to have a garden, it was going to be a serious garden, one with purpose, one that a family could harvest a meaningful amount of produce from.

Along that same vein of thought, it had to be cost effective. If it would cost more to raise vegetables than to buy them at the supermarket, that wouldn’t be acceptable. The garden had to offset its costs and in effect make a “profit.”

All of this brainstorming gradually clarified the objectives to the point where it was time to stop dreaming and start doing. I bought a notebook to use as a garden diary and entered the goals. The garden had to be:

1) Fairly small.

2) Manageable by one person.

3) Productive.

4) Cost effective.

The standards were set, this was the criterion. The next step was to attempt to translate the concept into reality—the actual establishment of the garden.

I now knew where the garden was going to be located; the sunny spot by the garage wall was perfect. But I didn’t want to just indiscriminately start digging.

Certain aspects had to be considered. It shouldn’t dominate the yard and it shouldn’t look like an open sore in the grass. Further, my children played back there, and kids being kids, thought had to be given to doing something to lessen the probability of them running all over it.

I had just read a book on French intensive gardening, a system that uses raised beds. The raised beds have the advantage of prolonging the season and promoting soil warmth and drainage. They also allow for close spacing of plants, a very important issue where gardening area is limited.

The merits of raised beds seemed to be unquestionable. Without a second thought it was decided to create my garden in that form.

As for the possibility of my children running into the beds, I reasoned that if framed with lumber that should identify those areas as garden, not to be disturbed. Looking back, I cannot recollect seeing any footprints in the beds, so it would seem that my logic was correct (although I can’t really be certain).

Since more than one bed would be needed, it seemed logical to make them in a modular form, all the exact same size. As a graphic artist I had used the principles of modular design many times in my work.

Modular design involves the use of modules to accomplish an objective. Modules are exact identical units, each being interchangeable with another. For example, a brick is a module, each is exactly the same; used together in different combinations, a wide variety of structures can be built.

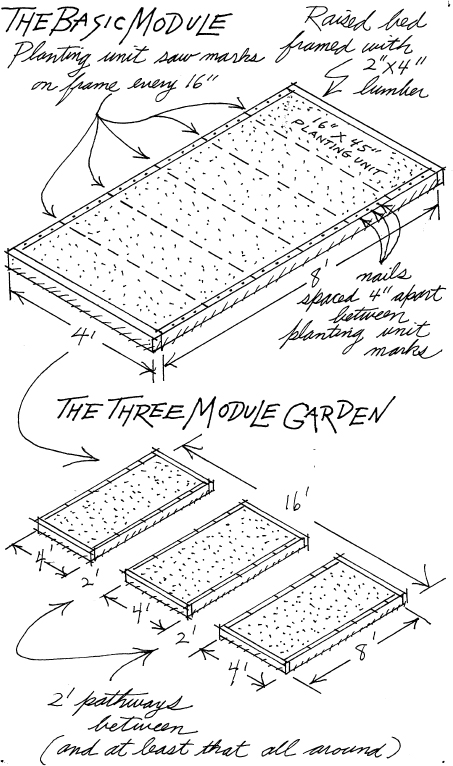

Determining the size of the modules was easy. Since standard size lumber comes in 8-foot lengths, 4 feet by 8 feet was the answer. This size requires only three 8-foot 2x4s for each module (one being cut in half). This size is also a convenient size to work. The bed can be easily reached into from all sides.

Note: Standard sized 8-foot-length lumber is sometimes slightly longer than 8 feet. If excessive, trim as necessary.

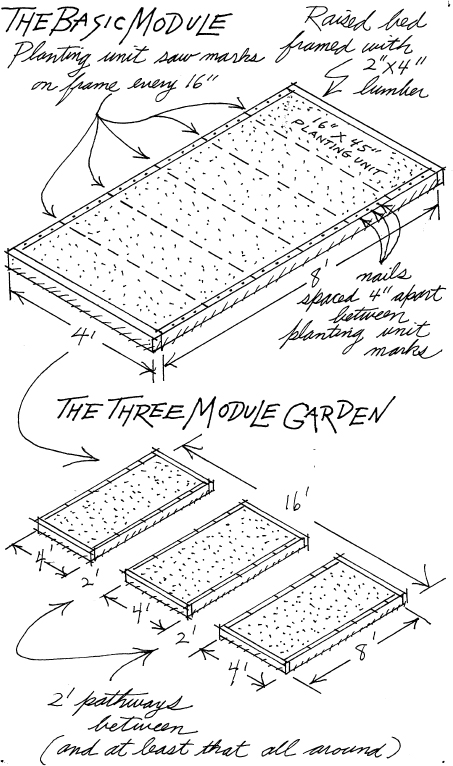

The area that had been selected would accommodate three 4- x 8-foot plots with enough room for 2-foot pathways between. Pathways are necessary because the beds should never be stepped into. They also act as barriers against soilborne diseases, preventing their spreading from one module to another.

Early one morning the area was measured out and, using a long-handled pointed shovel, the 4- x 8-foot raised beds were double dug. They were then framed with 2x4 lumber. The sod was retained in the 2-foot pathways. By the end of the day the three-module vegetable garden was established and looked good. With grass all around and in between on the pathways it blended in well with its surroundings. I was pleased with the results.

As per my criterion, I started out small, but as my enthusiasm grew, so did the size of my garden. It wasn’t long before I began adding modules. I became obsessed with attempting to grow every type of vegetable that existed. I read gardening book after gardening book, trying all of their “tips,” as well as all of their conventional, unconventional, and some just plain crazy gardening techniques.

About five years later, the garden had become much too big for me to keep up with. It had grown to double the size and took up more than half of the yard. Clearly I had strayed too far from my original criterion.

It was time to rethink and get back to the basic concept of a small garden manageable by one person.

To start, half modules were eliminated; then full modules. As modules were done away with, by necessity, the number of crops grown had to be reduced. A re-evaluation was in order.

Obviously, in a smaller garden, priority had to be given to crops that gave the greatest yield for space and effort. These were: lettuce, bush beans, beets, carrots, and tomatoes. All were vegetables much used by my family. They definitely had to stay.

Those being set, then came the painful process of culling out. In order to avoid eliminating any more than was absolutely necessary, succession plantings were increased. This had the added benefit of prolonging the harvesting season.

But, even with this, hard decisions still remained to be made. Each new season I would re-evaluate. One of the first to go was celery, with no regrets. Then corn, with many regrets. Celery had always been a difficult crop causing much frustration and little yield. Corn was another matter. Store-bought corn can never match the sweetness of the freshly picked homegrown. I still miss it, but it simply required too much room.

As season followed season, more difficult choices. Spinach, like corn, is another crop that has a tremendous difference in taste between homegrown and commercially grown. But facts had to be faced. It was always a problem crop, requiring precise timing, a lot of nourishment, and a quick bolting to seed the minute that the days began to lengthen. A lot of work for little in return: To drop or not to drop? My taste buds said no, but my brain said yes. Logic had to prevail. Spinach was dropped.

Now real progress was being made. The next year, zucchini with its sprawling growth was out, this was followed by the dropping of potatoes. The elimination of these two space hogs allowed for the introduction of broccoli into the garden, an easy to grow crop harvestable up into late fall.

As the garden was beginning to get down to a manageable size, one thing that became apparent was that much too much lettuce was being planted.

About half of it was bolting to seed unharvested. By cutting back on it, I was able to add Swiss chard and parsley: Two excellent additions. Both are long season crops. Both are very productive, and Swiss chard holds up in hot weather, furnishing salad bowl material when lettuce has just about run its course.

At this point, finally, the selection of what crops to grow was just about settled and my garden had shrunk back to my original three modules.

The smaller garden enabled me to notice details that had previously been overlooked. In a large garden there is room for error, if for any reason a few plants are lost, it is of no great concern. In a small garden efficiency is of paramount importance, every plant counts.

I began to experiment with different spacing between rows to see if more plants could be grown in a given area. Distances were varied between lettuce plants, some being spaced 6 inches apart, others 8 or 10 inches, trying to determine the optimum spacing. Other crops were handled in the same way.

Crop rotation also had to be reconsidered. With all of the changes, the old rotation was no longer applicable. Plus, two plantings a season were now being made in every bed: an initial planting in the spring followed by a succession planting later.

Not only did rotation from year to year have to be taken into consideration but also from initial plantings to succession plantings. A valid sequence had to be maintained throughout, within the season as well as from season to season. Not an easy thing to do, in fact it presented a real challenge.

The problem was addressed by spending many hours planning on paper what crops would be planted in what module. I just continued to move crops around until what seemed to be the right mix was arrived at.

At the same time my attention again returned to row spacing, trying to find a standard. Was it possible to find a “one-size-fits-all” solution? Over the years, measurements that are based on 2-inch increments were gradually arrived at. Spacing of rows are measured using multiplies of that increment.

After much trial and error, an area measuring 16 inches down the side of the module by the module width was found to be about the average space needed for any one planting. A module is 8 feet long (96 inches). When it is divided by 16 inches, it results in six 16- x 48-inch units (16- x 45-inch soil area). Since these “modules within a module” are the areas to be planted, logically enough, I call them “planting units.” A shallow saw mark was made at these points on both sides of the frame to identify them. Then between these marks, as a guide to row spacing, at 4-inch intervals 1¼-inch galvanized nails were driven.

The minimum space devoted to a crop is one half of a planting unit. The maximum space available in a module is, of course, the full module, six planting units.

These planting units helped greatly in planning sowings and crop rotation. In the winter months this became my favorite pastime, drawing up different possibilities of plantings and rotations; then evaluating the merits of each.

When all the planning and evaluating was completed, I felt that, finally, the criterion that was initially set had been achieved.

The garden was:

1) Fairly small. The garden consisted of three 4- x 8-foot modules. Lined up side by side with 2-foot pathways between, this occupied a space of 8 feet by 16 feet.

2) Manageable by one person. I was able to maintain it without difficulty. Depending on what had to be done, about a half hour or so after work on weekdays and an hour or two, or three, or four, or more, on weekends took care of all that had to be done.

3) Productive. The selection of vegetables was such that a long harvest was obtained, starting with cool weather crops in the spring, continuing with warm weather crops through the summer, and then finishing up with cool weather crops again into the late fall.

4) Cost effective. After the initial cost for lumber and tools, the only recurring cost was for seed and water. (Seed and water costs can be reduced by saving some of your own seed and using barrels to collect rainwater.)