![]()

WAY UP IN the atmosphere, currents of fast-flowing air zoom around planet Earth. Thousands of kilometres long, hundreds of kilometres wide and just a few kilometres thick, they steer our weather systems and, if you’re flying, can give the aircraft you are in the extra push it needs to get you home early. These mysterious aerial forces are known as ‘jet streams’.

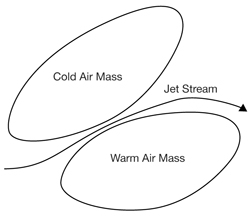

Jet streams occur about 10–12 kilometres (33,000–39,000 feet) above the surface of the Earth, where masses of cold polar air and warm tropical air meet. The different densities of these masses – cold and heavy, warm and light – mean a difference in pressure, and this forces air to rush at high speed from one to the other, creating the fast-moving bands of wind known as the polar and subtropical jet streams.

Instead of flowing directly from warm to cold, however, jet steams are deflected by the Earth’s spin and travel along the boundaries between the two masses, taking a meandering path. The main jet streams usually flow from west to east but sometimes they can change to almost north to south – all part of the atmosphere’s clever mechanism to transfer heat from the equator to the poles, and cold air from the poles to the equator.

The position of the jet streams is a clue to where the strongest contrast in surface temperature lies. The contrast is greatest in winter, so this is when the streams are fastest, accelerating to 300 miles an hour or more – over southwest Scotland, for example, speeds of 400 miles an hour have been recorded.

WATCH YOUR LANGUAGE!

Jet streak The tearaway of the skies – a pocket of extra-speedy wind within a jet stream that can blow at more than 320 kilometres (200 miles) per hour.

Because they are strong currents of fast-moving air, jet streams have the ability to steer different weather systems around. Knowing where the streams are, and how rapidly they are blowing, helps forecasters to predict what the weather is going to do. In Britain, for example, rain-bearing depressions (centres of low pressure, also known as cyclones) move in from the Atlantic.

However, if the Polar Front Jet Stream – the one that affects British weather – changes its usual easterly course it can steer such depressions away, or even block them altogether. Gazing into their crystal balls, forecasters are even worried that, should global warming increase sufficiently, this jet stream will move northwards, producing drought conditions over much of the UK in the summer. The winds in a jet stream do not always blow at a constant speed and at the points where they accelerate or slow down areas of low or high pressure can form, further influencing our weather.

Forming at a latitude of 60 degrees north during the winter at about 24 kilometres (approx. 80,000 feet) above the Earth, this strong band of winds controls the weather in the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

Located at about 7 degrees north of the equator at an altitude of about 15 kilometres (50,000 feet), this is another strong band of winds, which move from the east, from Asia across Africa, unlike the other streams, which flow from the west. It is strongest in July and August, in the Northern Hemisphere’s summer.

Lying 30 degrees north and south of the equator at an altitude of 13 kilometres (42,650 feet), this stream does not have a great influence on the weather, flowing above an area of fairly consistent high pressure.

Although they are weaker than higher-level streams – slow-coaches blowing at a mere 130 kilometres (80 miles) per hour or so – these can channel air northwards and southwards over several hundred kilometres and can have a dramatic effect on the weather. One such stream, forming at 4–4.5 kilometres (approx. 13,000–15,000 feet) over Africa below the Equatorial Jet Stream, and in the same summer months, makes its presence felt in the weather of the Caribbean and southern Atlantic. Huge thunderstorms can develop around it that move outwards across the ocean. If conditions are right and the sea is a toasty 27°C (81°F) or more, hurricanes can form.

• Wasaburo Ooishi, a Japanese meteorologist, was the first to suspect the presence of jet streams back in the 1920s, when he sent weather balloons up into the atmosphere near Mount Fuji to track winds at these higher levels.

• In 1934, American pilot Wiley Post took to the sky in a specially designed pressure suit that enabled him to fly at high altitudes. Way up in the heavens, at 15 kilometres (50,000 feet), he encountered a jet stream.

• The first usage of the term ‘jet stream’ was in 1939, when a German meteorologist, H. Seilkopf, coined the name in a research paper.

ON YOUR TAIL

During World War II, pilots flying between the United States and the United Kingdom noticed that the flight going east was quicker than that going west, aided by tailwinds of more than 100 miles an hour. In 1952, a commercial Pan American flight from Tokyo to Honolulu, travelling at an altitude of 7.6 kilometres (25,000 feet), reduced its journey time from eighteen hours to eleven and a half hours. Since then, aircraft have exploited jet streams, not only to shorten flight times but also to reduce fuel consumption.