![]()

THE CLOSEST ANY of us come to the clouds is when we fly in an aeroplane. We may literally travel through them and experience the strange sensation of being totally without visibility – or we may rise into the sunlit air above, and see them spreading out below us like vast swathes of cotton wool. But clouds are more than just fascinating aerial features: they can tell us a lot about what the weather is doing.

The great shifting masses that we call clouds are made up of countless tiny water droplets or ice crystals, or a mixture of both, that occur when air cools to a certain point. They form according to the three Cs: condensation, convection and convergence. A moist air mass may cool when it passes over an area of cold land or sea, to create low-lying cloud or fog. Or it may cool as it rises into the atmosphere because:

• it has been warmed from below, by the warm surface of the Earth – a process known as ‘convection’ – and so it floats upwards, cooling as it moves further from the surface.

• it is forced upwards by such physical obstacles as mountains.

• it meets a mass of colder, denser air and rises above it.

• it is forced into a restricted area – a process known as ‘convergence’ – and must rise to escape.

When air reaches a certain coolness, the water vapour – which is a gas – condenses back into a liquid, and tiny water droplets form. As the droplets accumulate, a cloud forms. If the temperature is low enough, the droplets freeze into crystals of ice.

WATCH YOUR LANGUAGE!

Orographic clouds Clouds that form when air is forced to rise above mountains or hills.

The term ‘a blanket of cloud’ is not far off – clouds do protect the Earth in a similar way to a nice, cosy blanket, or perhaps a thick layer of loft insulation. They work to insulate the planet from excessive heat loss, so if the night sky is cloudy, there is less likely to be a frost. They also reflect radiation from the sun back out into space, thus regulating the amount of solar energy absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere. Clouds are also not as moisture-laden as we think. An average cloud that is 1,000 metres (3,281 feet) high can produce only around 1 millimetre of rain.

DO IT YOURSELF!

Reading the clouds

Clouds may be divided into three main categories. They’ve been given Latin names which is useful because, if you know the translations, you can get a good idea of what each group looks like (see overleaf for clues) …

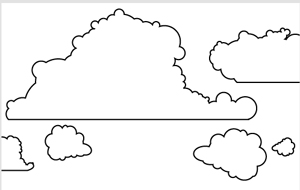

• Cumulus means ‘heap’ (as in ‘accumulate’) so these are the great piles of cloud that look like mounds of cotton wool, with a flat base.

• Cirrus translates as ‘a curl’ (of hair), so these clouds look feathery or hair-like.

• Stratus translates as ‘layer’, so these are low-lying clouds that may take the form of sheets of cloud without much definition – the ones we get on overcast days. Fog is a form of stratus cloud.

A further category was once used and is still found in combination with other cloud names:

• Nimbus means rain-bearing.

Now is when the fun begins. Simply by tacking on the appropriate prefix or suffix to the main group names, you can mix and match to describe a whole range of sub-groups of cloud. To help identify the different types, begin by looking at where they are in the sky – low down, at medium height or high up.

Lying low

Low-lying clouds begin about 2,000 metres (6,500 feet) above the ground and are usually made up of water droplets.

• Stratus form a grey, almost featureless blanket of cloud that is often accompanied by a light drizzle or snow.

• Cumulus clouds are a sign of thermals – columns of warm air rising from the ground – as you can see from the tower-like shapes at the top. They usually occur in fine weather.

• Stratocumulus look like separate rolls of grey or whitish cloud that form a sheet across the sky, and bring only light precipitation, if any.

• Cumulonimbus are the really dramatic ones – storm clouds that appear as white billows at the top, with dark, ragged, ominous-looking bases. Reaching high into the sky, they contain ice crystals as well as water droplets and are harbingers of rain, hail, snow, thunderstorms and, frequently, squally winds.

The middle way

Clouds lying at medium-height usually have a base between 2,000 metres and 7,000 metres (6,500–23,000 feet) above the surface and are formed of a mixture of water droplets and ice crystals.

• Altocumulus get their name from ‘alto’, which means high. They look a bit like balls of cotton wool, with dark shading and patches of sky in-between. If there is any precipitation, it rarely reaches the ground.

• Altostratus resemble stratus but are found higher in the sky, and create a hazy effect around the sun.

• Nimbostratus are the ones you’ll need your umbrella for – this dark grey, ragged layer of cloud hides the sun and brings almost continuous rain, sleet or snow.

High-wire act

Starting between 5,500 metres and 14,000 metres (18,000–46,000 feet) above the ground, high-level clouds are usually made up totally of ice crystals.

• Cirrus look like wispy white threads (although they may look grey if seen against the light). They are made up of falling ice crystals, but none of these reach the ground. Dense patches of cirrus clouds may obscure the sun.

• Cirrocumulus look like tiny tufts or ripples high in the atmosphere, often referred to as a ‘mackerel sky’ because they resemble the markings on that particular fish. Precipitation from these clouds rarely reaches the ground.

• Cirrostratus are perhaps the most subtle of all the types of clouds – they are visible as a milky veil of cloud, so thin that they don’t obscure the sun and aren’t accom-panied by any precipitation.