![]()

WE MAY NOT like it but we are in fact spinning in space on an outsized lump of rock, a.k.a. Planet Earth. Not only that, but the lump isn’t even upright – it’s whirling crookedly, at an angle. It’s this wonky tilt that is the cause of our seasons and the weather conditions that come with them, and the length of our days and nights…

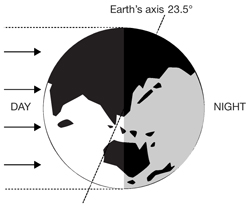

Imagine a rod running through the centre of the Earth, between the North and South Poles. This is the planet’s axis and it is tilted at 23.5°. The planet spins around this axis while at the same time orbiting the sun – a journey of 365 days, or a year. The Earth’s tilt means that different parts of its surface are angled towards the sun at different stages in its orbit, while other parts are angled away. The parts angled towards the sun get more hours of sunlight while the parts angled away get correspondingly less. The result? Varying lengths of day and night and changing seasons.

When the Northern Hemisphere is tilted towards the sun, the solar rays hit it more directly, giving more intense heat – and creating summertime. At the same time, the Southern Hemisphere is angled away from the sun, so the sunlight has further to travel and it is wintertime there. As the Earth travels on in its orbit, the South starts to point towards the sun and the North away from it, reversing the seasons.

DO IT YOURSELF!

Although global warming is effecting their movements, the flight path of geese is still a fairly good indicator of change in the seasons. Generally you will notice geese flying together in a ‘V’ shape, heading south when colder weather is on its way in winter, and will return when more temperate seasons come round.

Another good indicator of seasonal change that nature gives us is when the temperature of the soil is once again warm enough for plants to grow (at around 16°C or 60°F).

As the Earth orbits the sun, it spins around on its axis at the same time. Different sections of its surface revolve to face the sun in turn – and it is this that creates night and day. But the planet’s tilted axis makes it a bit more complicated than that. Although a region may have turned to face the sun so that it’s technically daytime, it will receive different amounts of sunlight depending on whether it is angled towards the sun or away from it in that particular period – and hence the varying length of days and nights in different parts of the world in different seasons.

The most extreme examples of this phenomenon are the Poles. If you were standing on, say, the North Pole in the polar summer when the Arctic is tilted towards the sun, you would enjoy twenty-four-hour daylight – for six months of the year. Conversely, in the Antarctic winter when the South Pole is angled away from the sun, there would be no daylight at all – just six months of darkness. Then there is the equator, which is the pivotal point of the planet’s axis – rather like the centre point of a seesaw. Here, the tilt is balanced out, giving roughly equal lengths of sunlight in summer and winter, and days and nights of about twelve hours each.

LOUSY SUMMER

The coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco.

Attributed to Mark Twain

Sunshine is associated with happiness and after the grey skies of winter nothing cheers like a bright spring day – and there’s a scientific basis for this. It begins in the hypothalamus, a control centre in the brain that is responsible for regulating such important bodily functions as mood, energy, sleep and sex drive. When sunlight passes through the retinas of our eyes, it stimulates the hypothalamus to release serotonin – a feel-good chemical – and slow down the production of melatonin, the hormone that makes us sleepy. In winter when sunlight levels are lower, we may experience SAD (seasonal affective disorder) and suffer from sleep problems, fatigue, depression, anxiety, irritability, overeating and loss of libido – and all because of a lack of adequate sunlight.

As well as lack of sunlight, the human body – and brain – struggles when the weather gets too hot and humid. In heatwaves, people:

• are more irritable and lethargic, find it harder to concentrate and have difficulty sleeping.

• turn to crime – excessively hot, sticky weather leads to irrational behaviour; in New York, for example, the regular summer crime waves are thought to be linked to the high temperatures.

• are more likely to die, especially if they are elderly – when the thermometer hits 38°C (100.4°F) or more, mortality rates increase by about 10 per cent.

Persistent, noisy, seasonal winds such as the mistral of southern France and the föhn of the Alps are another weather feature that can drive us humans mad, making us feel more tired, anxious and depressed – and, according to studies, more likely to have traffic accidents, commit crime or attempt suicide. Such winds can lead to temperature increases of as much as 15°C in just a couple of hours. The air in them is also positively charged which is not conducive to an upbeat mood. We respond much better to negative ions – atoms or molecules with a negative electrical charge – which explains why we usually feel better after a heavy downpour when the air is full of negative ions.