two

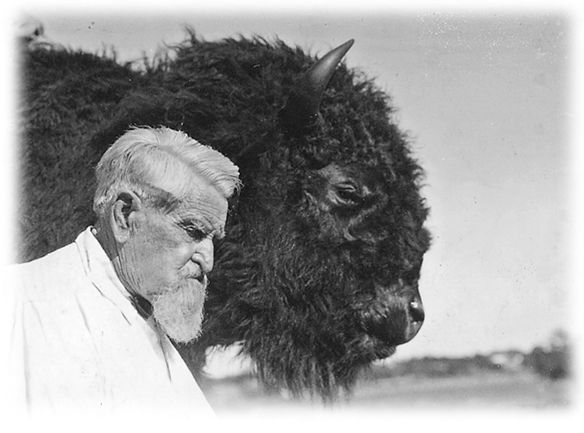

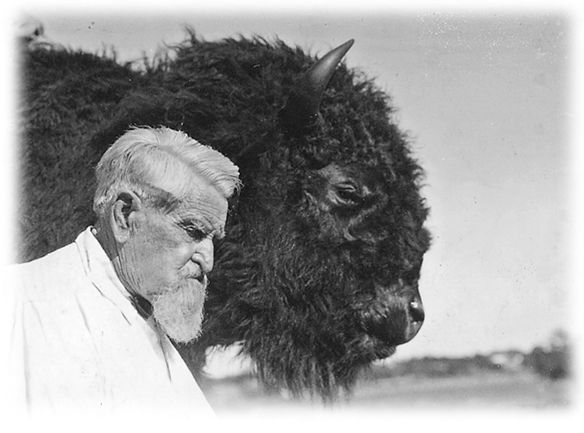

Charlie’s namesake, Charles Goodnight, saw his first buffalo as a nine-year-old boy in the 1840s along the banks of the Trinity River, today the site of downtown Dallas. Like most people, he had been fascinated by their strength and staggering numbers. By the 1870s, Goodnight had been a Texas Ranger, legendary trail driver, cattle rancher and breeder, and inventor of the chuck wagon—and was well on his way to being widely acknowledged as “Father of the Texas Panhandle.” Cattleman though he was, he was troubled by how rapidly the buffalo were disappearing; Goodnight realized that a world that had existed for thousands of years—a world that had belonged to the Indian and the buffalo—was coming to an end.

Once there had been 30 million buffalo in the United States, maybe 40. Some estimates (now considered by many to be grossly inflated) put the number as high as 80. Until 1860, even at the lowest number, there were more buffalo in America than people. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had found it impossible “to calculate the moving multitude which darkened the whole plains.” Another observer was more poetic: “The world looked like one robe.” The country was teeming with buffalo, herds of them hundreds of thousands strong, a vast shaggy carpet of buffalo miles long and miles wide. On first seeing them, men were apt to rub their eyes and question their sanity. There were places where the buffalo weren’t just on the land; they seemed to be the land. If you couldn’t see them, you could hear them coming, well in advance, an apocalypse on hooves. Sometimes it took days for them to run past a fixed point. Some claimed you could have walked ten miles across their backs without ever touching the ground. In his memoir, the prolific buffalo hunter J. Wright Mooar estimated the Southern herd in the millions. “For five days,” he wrote of a hunting trip in 1873, “we had ridden through and camped in a mobile sea of living buffalo.” For much of the nineteenth century, trying to calculate their number was a favorite pastime of hunters, settlers, naturalists, and soldiers.

Over the millennia, since the last Ice Age, the buffalo had come over the Bering Land Bridge from Asia, spreading east and south. Into the nineteenth century, they roamed what are now all the states in the continental United States except Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine. When the British explored Virginia in 1733, they found hordes of wild buffalo, “so gentle and undisturbed” that men could almost pet them. By the 1830s, however, the buffalo that had once roamed the East Coast from New York to Georgia had been virtually eliminated by Indians, colonists, weather, and disease.

By the 1840s, the buffalo population in the West had been whittled down as well. The buffalo on the west side of the Continental Divide were already gone, victims of the heavily trafficked Oregon Trail, with its endless wagon trains full of hungry settlers. That left the tens of millions of buffalo on the short-and long-grass prairies, but their days were numbered too.

History and progress had been conspiring against the buffalo for some time. The reintroduction of the horse to America by the Spanish in the seventeenth century gave man an animal fast enough to hunt buffalo efficiently. In the late 1600s, when the Pueblo Indians chased the Spaniards back to what is now Texas, the latter left behind some one hundred thousand horses, and now the Indians were in the buffalo-hunting business in a big way. By the 1830s, the steamboat penetrated the upper Missouri River into central Montana, opening the door to the cheap shipping of heavy goods, none more popular than the buffalo robe. Improved firearms were turning the art of buffalo hunting into an assembly-line industry. Indians had a name for the side-hammer, single-shot, extremely accurate Sharps rifle, able to drop a buffalo at several hundred yards; they called it “shoots today and kills tomorrow.” The completion of the transcontinental railroad dealt the buffalo a brutal triple blow, creating easy access to the dwindling herds and more cheap transportation—after 1872, primitively refrigerated too—to the growing markets for buffalo robes and tongues in Kansas City, St. Louis, and New York. Moreover, all those railroad workers had to be fed cheaply.

The buffalo had bigger problems, of course. For one thing, they weren’t cattle. The buffalo were taking up valuable grazing space and foraging land. The cattlemen couldn’t wait to get rid of their “buffalo problem.” Some say that homesteaders would have killed off all the buffalo eventually, to protect their farms, but the budding cattle industry was far more motivated. (The animosity toward the buffalo ran so deep in the culture of the West that, 130 years later, it would rear its ugly head in the wild buffalo’s only remaining refuge, Yellowstone National Park.)

Second, buffalo weren’t merely animals. Dead, they were the foundation of the entire culture of the Plains Indians—their chief source of food, shelter, clothing, fuel, ceremonial products, art, and commerce. From their skins, horns, bones, and sinew the Indians made robes, tipis, tools, combs, bowstrings, and sled runners. They had more than eighty uses for the buffalo.

The white man, of course, had exactly zero use for the Indians. The logic of Western settlement and westward expansion clicked into place; to clear the frontier of Indians—or, failing that, convert them forcibly from a nomadic into a confined, agricultural society—it would be necessary first to clear the frontier of buffalo. Although the Indians were at times wasteful consumers of buffalo, it had never been in their interest to squander the source of their survival. For the white man, fueled by political as well as economic zeal and an increasing taste for beef, the buffalo were an impediment. By the 1860s, Indians were already complaining of the wanton killing. “Has the white man become a child,” the Kiowa chief Satanta asked, “that he should recklessly kill and not eat? When the red men slay game, they do so that they live and not starve.”

The Indians were starving now, and this led to increased raids on government wagon trains, adding topspin to the vicious logic. Several famous remarks have come down to us from the 1870s to remind us that this logic was not just a construct of later historians. Army Colonel Richard Dodge reportedly told his men: “Kill every buffalo you can. Every buffalo gone is an Indian gone.” More reliable are the written statements from that time. Columbus Delano, President Ulysses S. Grant’s influential secretary of the interior, wrote in his 1873 Annual Report of the Department of the Interior: “The civilization of the Indian is impossible while the buffalo remains upon the plains.... I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies. . . .” In 1876, when Secretary Delano’s wish had almost come true, Texas Congressman James Throckmorton went on record saying, “I believe it would be a great step forward in the civilization of the Indians and the preservation of peace on the border if there was not a buffalo in existence.”

As Jared Diamond has documented in his book The Third Chimpanzee, there had never really been any question about the direction of the white settlers’ policy. “The Immediate Objectives are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements,” said George Washington. “This unfortunate race,” added Thomas Jefferson, “have by their own unexpected desertion and ferocious barbarities justified extermination. . . .” Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall intoned, “Discovery [of America by Europeans] gave an exclusive right to extinguish the Indian title of occupancy, either by purchase or by conquest.” Even Teddy Roosevelt, great friend of the West, would have a word or two about the Indians: “. . . this great continent could not have been kept as nothing but a game preserve for squalid savages.”

Could it get any worse for the animal once so plentiful that its herds couldn’t begin to be counted? The over-harvesting of beaver led to a shift in European fashion, to buffalo robes. On top of this, a major new industrial market for buffalo hides opened up. In the winter of 1871–72, one of the biggest hide dealers of the time, W.C. Lobenstine, was asked to provide five hundred buffalo hides for an English firm that wanted to experiment with turning them into high-grade leather, something that had never been done before. J. Wright Mooar, hired by Lobenstine’s agents for the job, killed 557 buffalo, sending the excess to his brother and brother-in-law in New York City and suggesting that they sell the extra hides to New England tanners to see what they might do.

“Even before the English firm had reported its success in the treatment of the buffalo hides, and asked for a large number of them,” Mooar wrote, “I was apprised of the fact that the American tanners were ready to open negotiations for all the buffalo hides I could deliver.” Overnight, turning buffalo hides into quality leather perfect for machine belting became big business. The hunters materialized, drawn by the news that a single buffalo hide might now fetch $3.50, a workingman’s weekly wage elsewhere. In the 1870s, an experienced buffalo hunter could drop a hundred animals on a good day, and after expenses he could make more money doing it than Ulysses S. Grant himself was paid to be president. Army officers often passed out free ammunition and horses to anybody who wanted to lend a hand. Soon the animals’ carcasses were left to rot, not even worth the effort of butchering once the bison had been skinned. As the killing frenzy intensified, many were killed—by Indians, too, now—just for their tongues, a delicacy.

For the gentry, the slaughter was presented as a game that combined the mystique of the American West and the manly allure of markmanship. The rich—women, too—paid handsomely, even came all the way from Europe, for the privilege of shooting buffalo from fancy carriages and chartered trains. Buffalo Bill Cody, who would later become wealthy reenacting “unsuccessful” Indian attacks on stagecoaches and white settlers as entertainment (using real Indians as actors, no less), served as grand marshal for a hunt with the Russian czare-vitch. The well-heeled simply removed their top hats and shawls, leaned out the windows, and fired. It was a carnival shooting gallery with real ammunition and targets. In 1869, Harper’s magazine featured an engraving of men shooting buffalo from the windows and roof of a moving train, with the writer and illustrator Theodore Davis’s verbose caption: “It would seem to be hardly possible to imagine a more novel sight than a small band of buffalo loping along within a few hundred feet of a railroad train in rapid motion, while the passengers are engaged in shooting, from every available window, with rifles, carbines, and revolvers. An American scene, certainly.”

What John J. Audubon and others had predicted as far back as 1843 was a reality by the winter of 1882–83. The railroad records tell the story: In 1882, the Northern Pacific Railway moved two hundred thousand hides out of Montana and the Dakotas, but the number dropped to forty thousand in 1883, and a mere three hundred in 1884. Along the way, many had called for state laws to protect the buffalo, but only the Idaho Territory passed legislation, and it was weak, prohibiting hunting for only five months each year in an area where the buffalo were relatively scarce anyway. The Dakotas, like several other states and territories, passed buffalo-protection laws in the 1880s, but the bison were already out of the barn, and dead. On the federal level, Congress finally got around around to passing legislation in 1874 to limit buffalo hunting, but President Grant promptly pocket-vetoed it.

Just as white men had been stunned by their first glimpse of the numberless buffalo decades before, many were stunned again by what they had done, and refused to believe that the animal to whom this country had belonged, as to no other, whose bountiful gifts had supported an entire civilization, was practically extinct. The vast carpet had been reduced to an endless blanket of bleached bones destined for fertilizer, carbon black, and fine bone china for the carriage trade. Teddy Roosevelt told of a rancher who, crisscrossing the length of northern Montana, was never out of sight of a dead buffalo, or in sight of a live one.

The photographs of massacred bison and stacked hides gave way to photos of piles of buffalo bones in factory grounds. In one famous image from the 1880s, a man at the Michigan Carbon Works in Detroit stands atop a mountain of buffalo skulls forty feet high. At the bottom of the mountain, another man poses for the camera, a foot perched on a buffalo skull plucked from the pile. Though not the hunters, the men nonetheless look triumphant, proud to play even a small role in the buffaloes’ demise. It’s as if they are the beaming curators of an exhibit of man’s victory over nature. Buffalo? What buffalo? We didn’t see any buffalo. America was a land of plenty, including plenty of bones that used to be buffalo. No one was going to let a small thing like 30, 40, 50 million buffalo get in the way of a destiny as manifest as America’s.

In one form or another, bison had been on the earth for almost a million years. Between ten thousand and thirteen thousand years ago, at the end of the Pleistocene Era and the last Ice Age, almost all of the several giant North American mammals—fifty-foot-long alligators, ten-foot-high carnivorous birds, and 1,500-pound guinea pigs—became extinct, as a result of hunters, climate changes, and possibly other natural catastrophes. Huge horses, camels, woolly mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant short-faced bears were, after surviving almost two dozen other Ice Ages, suddenly gone forever.

Only one of the bigger beasts survived: the buffalo. What climate changes, evolution, and four-legged predators couldn’t accomplish for hundreds of thousands of years, humans nearly did over the course of a few decades.

IN OCTOBER 1876, when the Great Slaughter was well along, forty-year-old Charles Goodnight laid eyes for the first time on the Palo Duro Canyon in the Texas Panhandle. He had seen no buffalo on the tableland, so he was surprised to find ten or twelve thousand of them grazing on the canyon floor. But he was less interested in buffalo than in cattle; he was about to establish the first ranch on the Texas Panhandle, the JA, in partnership with an Irish financier named John Adair, and he realized he was looking at the perfect place to do it.

Where once it was covered with enough grass for both cattle and buffalo, today the ten-mile-by-hundred mile Palo Duro is overgrown with cedar, scrub oak, mesquite, and yucca. The JA is still in operation, the oldest continuously owned ranch in the Panhandle. Its owner, Ninia Ritchie, who is descended from John Adair, has a state-of-the-art kitchen in the greatly expanded main house, stocked with food and delicacies from all over the world, and if she needs shallots or Bibb lettuce, all she has to do is drive along the canyon’s rim to towns like Claude and Clarendon. However, when Charles Goodnight brought his wife Mary Ann—he called her Molly—down from Colorado to be with him, the place might as well have been Mars for all the amenities it provided.

Charles, whose great-grandfather had come from Germany and settled in Virginia in the 1750s, always thought he had married above him. Mary Ann Dyer was a schoolteacher whose family included a governor of Tennessee. She was a strong, independent woman who had raised her two brothers after their parents’ deaths. Mary Ann didn’t frighten easily. But at the end of the trip to the Palo Duro, when the traveling party camped one night with its 1,600 head of cattle on a mesa overlooking the canyon, she heard a sound that scared the wits out of her, a terrible rumbling coming closer, clearly soon to engulf them. Charles finally convinced her it was only a stampede of bellowing buffalo that, despite the roar, was a mile or two away in the canyon. “Mrs. Goodnight, not being accustomed to such scenes, became greatly alarmed, saying they would run over the wagon,” Goodnight would say many years later. Not only could he see that she wasn’t fully convinced, but an actual thunderstorm promptly began, so he built a blazing fire, “assuring her that buffaloes would be easier turned by a light than a cavalry charge.” As she cowered on top of the mesa, Mary Ann would have been surprised to know how big a role buffalo were to play in her life, and she in theirs.

The next day, Goodnight drove the cattle down the narrow entrance to the canyon. “As the canyon widened,” he remembered, “the buffalo increased till finally by the time we arrived at the upper end of the wider valley . . . we supposed we had ahead of us ten thousand buffaloes. Such a sight was probably never seen before and certainly will never be seen again, the red dust arising in clouds, while the tramp of the buffaloes made a great noise. The tremendous echo of the canyon, the uprooting and crashing of the scrub cedars made one of the grandest and most interesting sights that I have ever seen. If they did not come off the mountain sides that were near us we simply sent a sharp-shooter ball amongst them. A nearby shot caused an instant stampede, making kindling wood of the small cedars as they came.”

In a two-room log cabin, still standing today as the oldest part of the sprawling JA ranch house, Mary Ann Goodnight tried to make a home, the first in the Texas Panhandle. She lived in a world of howling winds and cowboys who didn’t say much. She patched their clothes, sewed on their buttons, treated their illnesses and injuries, and tried to engage them in small talk. Her isolation was so great that a sack of three chickens utterly transformed her social life during that second winter. When a cowboy brought them by one day, she knew better than to cook her new feathered company. “No one can ever know how much pleasure and company they were to me,” she would reminisce. “They were something I could talk to, they would run to me when I called them, and follow me everywhere I went. They knew me and tried to talk to me in their language.”

She eventually imported what she could from civilization, including a New York artist she commissioned to travel down to Texas to paint local landscapes that she could hang on her walls. Her husband, however, was aware of what he had gotten her into, and many years later he gave her a clock inscribed:

IN HONOR OF

MRS. MARY DYER GOODNIGHT

PIONEER OF THE TEXAS PANHANDLE

For many months, in 1876–1877, she saw few men and no women, her nearest neighbor being seventy-five miles distant, and the nearest settlement two hundred miles. She met isolation and hardships with a cheerful heart, and danger with undaunted courage. With unfailing optimism, she took life’s varied gifts, and made her home a house of joy.

Mary Ann survived the first couple of winters and even came to love the rugged, demanding life of a rancher’s wife. She would later view these years as among the most exciting she had ever known—made even more suspenseful by the occasional unscheduled visit from Comanches or Kiowas. Her trepidation about hostile Indians was eased greatly by her husband, a man of great integrity and tough compassion who treated Indians fairly, was treated fairly in return, and made several lifelong friends among them. Mary Ann’s other fears—of buffalo stampedes, rattlesnakes, the merciless winter winds, and the great isolation—also gradually abated.

There was one thing, however, that she never got used to: the endless killing of the buffalo. Day after day, she could hear the reports of the new long-range breech-loading rifles—the “Big Fifty” .50-caliber Sharps and the Remington—that had been added to the list of the buffaloes’ woes. The rifles were followed by the buffalo skinners, whose teams of horses would pull the buffalo hides clean off them, then dry them on stakes, flesh side up. As Mary Ann did her chores, preparing simple meals and conversing with her chickens, she was haunted by the guns in the distance.

Mary Ann, who was childless, asked her husband if he would rope out a couple of orphaned buffalo calves for her before it was too late. She would try her hand at raising them herself, safe from the sharpshooters and the safaris. Charles was a practical man; at first, he didn’t think much of his wife’s idea. After all, he was a cattleman. On the other hand, he had great respect for the buffalo, which he believed to be smarter than the horse, the antelope, and the cow (except, perhaps, when it came to a propensity to go through, rather than around, fences and bodies of water). Buffalo, he had observed, never used deception to protect their young, but confronted their enemies and fought without regard for their own safety. They could go twice as long without water as a cow could, and could smell a water source from miles away if they were downwind of it. Not only did they eat about a third less grass than cows, but, thanks to two more incisors, they were better at finding and eating it. In winter, buffalo used their heads, massive neck muscles, and beards to whisk away snow to reach dead grass that cows couldn’t find. Neither wind, water, nor cold could penetrate a buffalo’s dense coat. Its hair held so much heat that on a sunny winter’s day you could put your fingers down into its coat and barely keep it there, it was so hot. Unlike cattle, which during severe storms tended to drift to low spots and get trapped or buried, buffalo survived by facing into the storm. Sometimes they’d even head slowly into a storm, shortening their time in it. In warmer weather, the animal was a highly efficient roughage feeder—a veritable mowing machine—as well as an ecological miracle: Unlike cattle, who wore grooves in the soil, killing the grasses, buffalo grazed in tight, wandering herds, eating the grass down to the soil, then moving on, giving grassland as much as two years’ rest before they came around again. In the spring, they rolled around, shedding grass seeds caught in their coats since the previous fall. They replanted the soil. They gave back, fertilizing the prairie with their nitrogen-rich urine and, eventually, their decomposing bodies. (It would be another 130 years before their ecological importance to the grasslands was appreciated by a new generation of scientists and preservationists committed to the dream of restoring the American prairies.)

Charles Goodnight, in fact, had actually tried to start a domestic herd a dozen years before. The mother of one of the calves he roped out had attacked him so savagely that he had had to kill her to save his horse—an act for which he never quite forgave himself. Eventually he gave his six buffalo calves and their foster-mother cows to a friend to raise for a 50 percent stake in the herd, but the friend lost interest, sold the herd, and never gave Goodnight his cut. The whole affair left a bad taste in his mouth. Still, he thought, waste was a sin—his cowboys used to scatter nails around the ranch just to see Goodnight pick them up—and what was happening to the buffalo offended his moral nature. Goodnight was also a loving husband. So, between one thing and another, he presented Mary Ann with two yearling buffalo, a male and a female, soon to be joined by four more.

Mary Ann bottle-nursed the six calves until they were strong. A few more came along, and some of them started having calves of their own. The years passed and Charles Goodnight’s cattle ranch and prosperity and fame grew, and so did their little herd of buffalo. It grew to fifteen animals, then thirty, sixty, a hundred and twenty. By the time Charles Goodnight died in 1929, the herd numbered two hundred and fifty.

The vast majority of the North American buffalo alive today are descendants of a few wild survivors who took refuge in Yellowstone and about eighty calves that were hand-raised 120 years ago in Montana, Manitoba, and the town of Goodnight, Texas.