eleven

A few days later, Dr. Callan called to say that Charlie was ready to go home.

“He’s doing great,” he told Roger. “But, remember, he’s a three. You’re going to have to keep an eye on him.”

On January 26, 2001, three weeks to the day after Charlie had arrived at the Colorado State University Veterinary School of Medicine, Roger and Veryl drove up to get him. It was her fifty-forth birthday and Charlie’s present was that he was waiting for them, standing in his stall. Tears sprang again to Veryl’s eyes.

They backed up the horse trailer to the dock opposite Charlie’s stall. Charlie recognized it immediately; he had always liked the trailer, had always liked to go places. He took one look and began walking unsteadily toward it. Once inside, Charlie lay down contentedly between the two rows of fresh hay bales Roger had used to keep him sternal and cushion the ride, then gave Roger an expectant look.

The drive home was the opposite, emotionally and geographically, of the one up from Montosa Buffalo Ranch three weeks earlier. Roger and Veryl felt as if all the exhaustion and anxiety had been packed up, crated, addressed to the past, and mailed off. When they got back to the house, Roger backed the trailer up to the barn and led Charlie carefully down the ramp. But as soon as his legs hit the red brick barn floor, he began to lose his balance. Although his forelegs were strong, the rear part of his body was twisted to the left, forcing his shaky left hind leg to cope with a disproportionate amount of body weight, while the right hind leg, the more visibly affected, jerked forward with every step. His legs crumpled and he fell on his side with a thud.

As Roger helped him up, he knew that their work was not over, but only just beginning. He made a path of wood shavings in the barn to give Charlie traction going in and out of his stall, which he lined with hay bales to break Charlie’s falls. In other places he put down rubber mats. He would need to spend as much time as he could with Charlie; his job description for the near future could be summed up as “keeping a buffalo from falling.”

The worst of it was seeing how much this hurt Charlie’s pride. Roger didn’t think he had ever seen an animal as depressed as Charlie was after he had fallen. It was difficult to witness helplessness in a creature so large. But accidents could not be prevented. The damage was mostly psychological. Now he was hesitant to look Roger or Veryl in the eye. His grunts had become low grumbles. Roger knew that if Charlie kept falling with any regularity, he would soon get discouraged and give up on walking altogether.

Humans have a hunger for hope. Wounded or diminished animals know when their time has come and slink or crawl off to meet their fate halfway. Most people tend to go in the other direction, frantically scanning the landscape for the faintest message of salvation. Despite the very guarded prognosis from Dr. Callan, Roger and Veryl had proceeded to build a house of hope that Charlie, they soon realized, might not be able to live in. There were dinners together when Roger and Veryl could barely speak to each other because the only things that could possibly come out of their mouths were things neither of them wanted to hear. They were so depressed by Charlie’s lack of progress that sometimes they forgot to be grateful that he was alive at all.

For the first time since Charlie’s first few days at CSU, Roger began thinking the unthinkable—that maybe Charlie wouldn’t make it back, maybe he would never even be pasture-sound. If Charlie couldn’t stand without falling when he weighed five hundred pounds, what would happen when he grew to one thousand, then two thousand pounds? Charlie was gaining a pound or two a day. Could his legs support his weight as he got older and bigger? If not, he would become a complete danger to himself and anyone around him.

Roger sat on a hay bale in Charlie’s stall one moonlit night, pondering life’s contingencies, while Charlie lay quietly in the darkness, his big head resting against Roger’s leg, his indigo shadow spilling across the barn floor. If Veryl hadn’t been sent a Texas Highways magazine feature about her ancestor Charles Goodnight, she wouldn’t have needed a buffalo calf in the first place. If Charlie’s mother hadn’t had to make the correct evolutionary choice between her herd and her calf, he never would have come into their lives. If he’d come into their lives, but they’d owned other buffalo, they might have been able to keep him. If Roger had spent more time acclimating Charlie to his new life at the Montosa Buffalo Ranch, easing him into the new situation, Charlie might not have run into the fence, and he might now be living with a herd. If, if, if. Life was a few acres of experience enclosed by a fence of ifs.

Not much more than a hundred years ago, buffalo had been slaughtered by the millions to make room for settlers and cattle and progress and fences—and yet here was a single buffalo, Roger mused, unlike any other. How strange that so much of life took the form of teeming, meaningless masses, yet its highest expression was what happened between just two beings, even a man and his hobbled buffalo.

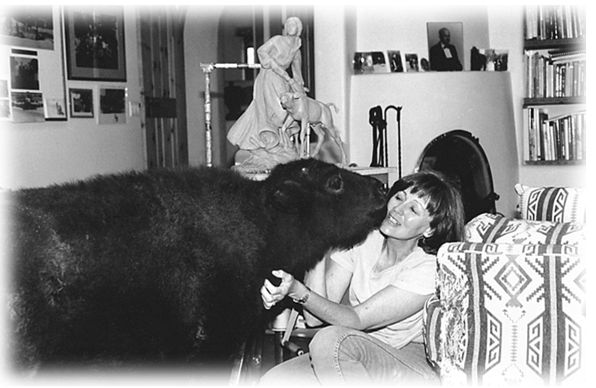

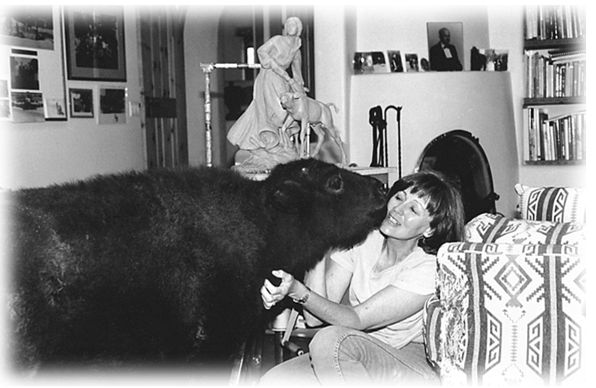

Over the next few weeks, Charlie became a little more stable and recovered some of his pride. He and Roger started taking walks again, short ones. It wasn’t like the old days. Charlie walked crookedly, his hindquarters twisted to the left. He still hoisted his hind right leg forward in an arc. He was slow going up and down the small rises and falls of the hills near the house. Roger made sure he was always on Charlie’s left, the direction in which he almost always fell. As soon as Roger saw Charlie start to lose his balance he’d lean his hip hard against him with all his strength; it was often enough to stabilize Charlie’s five hundred pounds. But sometimes it all happened too quickly, Charlie would take a spill, and Roger would wait patiently for him to get slowly to his feet. To protect Charlie’s feelings, he made a conscious effort not even to look at him. He would pretend it hadn’t happened at all, except that when Charlie got up Roger couldn’t resist the urge to reward his courage in one of the languages Charlie understood best—Carrot.

For weeks, it was touch and go with Charlie, some days better than others. Even on the better days, though, Charlie had trouble changing directions or turning around. He’d be walking in five directions at once. Then he was going only in four directions, then three, then two. There wasn’t any one particular day when Charlie improved dramatically. It was like watching a lot of things—a flower unfolding, winter turning to spring, or a child growing up.

Then, like suddenly seeing your daughter in her eighth-grade graduation gown and high heels, there came one moment—a late afternoon when he watched Charlie trotting, however uncertainly, toward him in the corral—when Roger knew that everything had changed. He realized that it had been quite a while since he had last thought that Charlie might not make it. He and Charlie had graduated from uncertainty. Roger ran up to the house, tore Veryl away from her sculpting, and took her down to the pen, where they stood hand in hand in the thick light of the setting sun and watched Charlie lower his head and go to town with his sparring partner, the now badly beaten fifty-five-gallon plastic drum.

The next day Roger picked up the phone to tell Dr. Callan about Charlie’s progress.

“His butt’s a little twisted to the left and he doesn’t like to put much weight on his right hind leg,” Roger said, “but he’s pasture-sound and then some.”

“Great news. I have to hand it to you.”

“He couldn’t have done it without you, Doc. And everyone else up there. I’m really thankful.”

“There was nothing special about the medical care. Just the buffalo.”

“We told you he wasn’t your average bison. You know, he’s turning one year old in a month. Rob, what’s a buffalo’s life expectancy?”

“In the wild? Fifteen, twenty years. Their teeth wear out from foraging. Although I’ve read of buffalo who got so old their horns just decayed and fell off. In captivity, they can go generally go thirty years, maybe more. Charlie could live that long.”

Roger laughed. “Like a son who never leaves home.”

THE NEXT DAY Roger was on the phone with his lawyer.

“You want to what?”

“I want to change my will to provide for the buffalo.”

“That’s what I thought you said.”

“I want to name a trustee for Charlie when Veryl and I are both gone and make sure there’s plenty of money for his care and feeding.”

“You’re talking about a buffalo.”

“He’s going to outlive us. You’ve got to come over and see him.”

“If I want to see a buffalo, I’ll look at a nickel.”

“They haven’t made buffalo nickels since the nineteen-thirties.”

“So I’ll go on eBay and look at one.”

“You’d rather look at a nickel on your computer than come over and say hello to the most extraordinary buffalo ever?” Roger said. “That’s very insulting to Charlie.”

“Insulting? Roger, it’s bad enough you’re putting a buffalo in your will. Don’t tell me he’s got feelings too.”

“More than your average lawyer,” Roger said, laughing, happier than he’d been in a long time.