twelve

The fact that Charlie was out of danger and arrangements were under way to provide for his future care didn’t make Veryl and Roger’s job easier. The sculpture of Charlie that Veryl was now working on—“Tomorrow’s Leader,” she would call it—captured the paradoxes of a yearling bull bison. In the sculpture, Charlie is caught between calfhood and adulthood. His legs, a little too big for his body, seem to jut out in too many different directions. But his beard and pantaloons are coming in. His horns are now about six inches long, long enough to keep any remotely intelligent human at a comfortable distance. He has a modest but unmistakable hump. Although there is a balance to his physique, the weight fairly equally distributed front and back, all of the eventual mass and power of his head, hump, and shoulders is now implicit in this intermediate form. Veryl has given Charlie an anxious expression. Something unfamiliar, possibly threatening, has caught his eye. His tail is standing up, a sign of alertness, if not belligerence. Perhaps he has spotted a wolf at the edge of the forest and is sizing him up, or maybe he’s looking at a full-grown bull bison and wondering, with all the insecurity of adolescence, how he will ever grow into that.

In a brochure for a show featuring “Tomorrow’s Leader,” Veryl would include a quote from the nineteenth-century naturalist William Hornaday on the subject of one-year-old bull bisons: “Like a seventeen-year-old boy, the young bull shows his youth in so many ways it is always conspicuous, and his countenance is suggestive of a half-bearded youth.”

Roger and Veryl now developed fresh anxieties about how to manage him. Like the parents of an adolescent, they fretted over the right formula of freedom, discipline, and benign neglect. They lost sleep over it. It wasn’t as if you could call 1-800-BUFFALO and ask a customer representative what an unusually tame teenage bull buffalo living alone needed if he was to feel really good about himself.

In particular, they worried that he might be lonely. The older dogs, Luke and Mickey, were no longer interested in playing with him. Especially Mickey, on whose favorite Frisbee Charlie had been inadvertently standing one day; Mickey’s desperate, incessant barking had finally lured Roger from the house to liberate the toy. The hair on Charlie’s forehead was growing in thickly. In time, it would be four inches thick, enough to absorb the shock of a frontal assault from a rival he would never have. In time, Charlie would have ten times as much hair per square inch as a cow. With his horns and beard coming in and his pantaloons making him look like he was wearing baggy clamdiggers on his forelegs, Charlie was no longer the playful calf the dogs once knew. To them, it must have seemed as if that animal had been traded for a beast who wanted nothing to do with them. The two newest additions to the Brooks-Goodnight household, a Rottweiler named Flag and her mixed-breed daughter, Annie, were just plain confused at first. Flag, however, turned out to be a highly maternal and solicitous animal, and soon she was accompanying Roger and Charlie on their walks.

Since it was buffalo that scared him off at Montosa, Roger and Veryl considered goats and burros as potential playmates. To test Charlie’s sociability, however, they settled finally on a young Longhorn steer offered on loan by some friends of theirs. Roger and Veryl named him T-Bone—a name designed to inhibit any potential emotional attachment—and one bright blue afternoon they threw him into the arena with Charlie and watched while the two animals got to know each other. Or, more precisely, didn’t. If Charlie were a five-year-old boy instead of a one-year-old buffalo, his kindergarten teacher would no doubt write in his progress report: “Doesn’t play well with others.” The report for T-Bone would have been even less flattering, and included the phrase, “schoolyard bully.”

At first, the two animals ignored each other, so Roger and Veryl left them alone. But after a few days Veryl heard such a ruckus from her studio that she ran out to the pen to find T-Bone mercilessly chasing Charlie around. She picked up a tree limb, jumped in the arena, got right between them, and started waving it around at the steer. Undeterred, T-Bone took off after Charlie again, so Veryl wound up and heaved the limb at him, striking the steer’s shoulder. Then she drove him into the adjacent enclosure.

“It’s not working all that well,” Roger reported to T-Bone’s owners that evening.

“We forgot to tell you he’s got some Coriente in him.”

Roger was shocked. Coriente was a rather hot-blooded Mexican breed of cattle—not exactly the assortment of genes you’d choose in a prospective playmate for an impaired buffalo. T-Bone stayed in his own enclosure for another week or so—giving Roger, as well as Charlie, some angry looks—before Roger had time to drive him across New Mexico back to his home.

Roger concluded over dinner one night that maybe Charlie wasn’t so lonely after all.

“Sweetie,” Veryl said, “we’re his herd.”

Not only was Charlie not especially lonely, but he was becoming more independent. Charlie didn’t greet Roger quite so often with a grunt. Inside every young male buffalo is a loner waiting to emerge. In the wild, bulls keep mostly to themselves except during rutting season, when they rejoin society to escort, or “tend,” the females of their choice in preparation for mating. They live apart from the herd, alone or with a like-minded buddy or two, the bison equivalent of two octogenarians on a boardwalk bench. For the first time, Roger had a glimpse of Charlie’s solitary, dignified future.

For the time being, though, there was nothing particularly dignified about the way Charlie expressed his independence and territoriality. Keeping him in the back yard was no longer an option, given his penchant for trampling small trees or picking a fight with the lawn furniture. Charlie was now confined to the barn and fenced arena—at least in theory. Late one night, Roger was awakened by a noise coming from the carport and went to the window. In the darkness, all he could make out was the silhouette of a massive hump gliding ominously, like the shark’s fin in Jaws, between Roger’s Saab and his cherished 1958 Studebaker Silver Hawk.

The thought of Charlie absentmindedly dragging a horn tip across the paint job was too much, so Roger began taking extra care that the corral gate was secured with slide bolts against Charlie’s growing restlessness and ingenuity. But to err is human, and one day Roger forgot to fasten the gate. This time it was a truck that paid the price. Roger and Veryl had hired some men to come over and drill a new well. One of them, Jimmy, smelled of sheep since he and his father owned a herd of them, and the odor was more offensive to Charlie than the workers’ invasion of his territory. Charlie did not want to be around the smell of other big animals any more than he wanted to be around the animals themselves, so he ambled up to the front of the property near the road, where the drillers had parked a brand new pickup truck, and began pawing the ground and snorting and bellowing.

The phone rang in Roger’s office near the front door, and he picked it up to hear Jimmy’s co-worker on his cell phone saying that Jimmy was now standing on top of his truck, which a buffalo was proceeding to attack. Roger was out of the house in a flash, followed closely by Veryl, but by the time they had sprinted up to the top of the driveway, the damage had been done. Charlie had head-butted a big dent in the door of the pickup while Jimmy surveyed the scene from the truck’s roof.

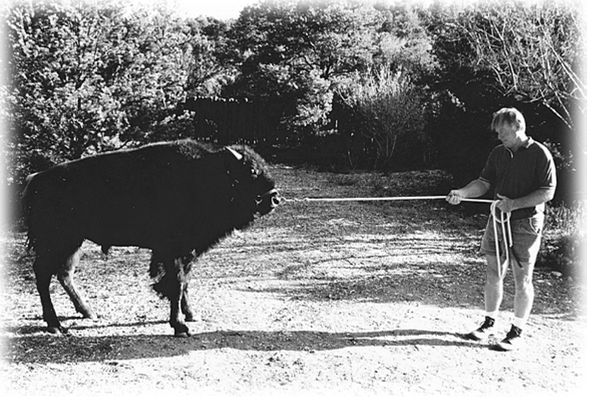

As humiliating as it must have been for a cowboy to be “treed” on top of his own truck by the world’s tamest buffalo, it had to be even more galling to be standing on top of your own truck with a buffalo snorting at you from below while a middle-aged couple hand-fed him baby carrots and then threw a lasso around his horns and led him away like a rambunctious family dog.

Still, and with some regularity, when Charlie was not in a mischievous mood, Roger could now get him to come just by calling, and could get him to go in a certain direction just by pointing. This degree of influence may be no great accomplishment with a dog, but it’s a rare cat who’ll stand for it, and you had to see it to believe it in the case of a buffalo. It was no accident. Roger had long ago achieved a similar level of intimacy with his now twenty-two-year-old horse Kepler, and he’d done it through trust—by never asking the horse to do something when Roger was in the saddle that Roger hadn’t already taught him to do on his own. Roger never had to halter Kepler until they were outside the pasture gate. He could get him to follow just by touching his cheek. Kepler was so attuned to Roger, and Roger only, that he was never distracted by other horses. Charlie was the same way. On a good day, when he and Roger were together, nothing else seemed to matter.

Roger liked to think about the next step in relationships. He liked to think about it the way other men daydream about playing the Old Course at St. Andrews or skiing Copper Bowl in eighteen inches of new powder. He liked to think about building blocks of trust, the architecture of intimacy. He liked to think about setting the stage for the next stage. As a result, he had never given Charlie a reason to dislike him. Of course, a buffalo was not a horse. Horses had been bred to do man’s bidding; as far as buffalo were concerned, man hardly even existed. They had never learned to fear man or, sadly, his bullets. Buffalo belonged to themselves, so the trust that Charlie developed in Roger had no measure of fear in it. It was Roger whose trust in Charlie had to be constantly balanced by a legitimate concern for his safety.

Exercising Charlie in his pen was fraught with fresh dangers. For instance, Charlie had a new game called “Let’s Pretend I’m Charging You.” The problem with the game was that, from the human participant’s point of view, until the very last moment there was really no difference between a buffalo pretending to charge you and a buffalo who is actually charging you. Had Roger been prone to forgetting, which he was not, that despite all Charlie’s advantages in life and the refinements of his character he remained, instinctually, a wild animal, these were the moments when he would have been reminded of that fact.

Roger was careful to teach Charlie how to transition from rough play with one of his “toys” to affectionate play with him. For the most part, Charlie understood that a plastic drum was one thing and Roger’s body another. The line, though, wasn’t always precise. On a couple of occasions, when they were playing together in the arena—watching them was like watching a dad shadow-box or play-wrestle with his gargantuan ten-year-old son—Charlie used the side of a horn to parry Roger’s arm. This was new. One thing buffalo always know is precisely where the tips of their horns are. They do not wield them thoughtlessly. So Roger understood this as a gentle warning that the boundaries had been moved, and the penalty for violating them would now be more severe. A nervous or displeased horse will get skittish and run. An unhappy buffalo is different; he’ll simply lower his head, nose to the ground, and give you a good look at the lethal tips of his horns. Charlie wasn’t above showing Roger his horns, and Roger wasn’t above backing off from a fight he could never win.

Walks were becoming fewer and farther between because of Charlie’s unpredictability. On one walk, Roger told him it was time to go back to the barn and pulled his lead in that direction. Charlie responded by “accidentally” catching his horn in the pocket of Roger’s shorts. This was not one of the old buffalo wedgies of Charlie’s childhood; this time, the bigger, stronger version of Charlie lifted Roger clean off the ground so that only the toe of one sneaker was still touching.

“That’s not funny, Charlie,” Roger yelled. “Put me down.”

Charlie chewed his grass.

“What part of ‘Put me down’ don’t you understand?”

It was as if the 230-pound man on Charlie’s horn was of no more concern than a fly on his nose.

“Okay,” Roger said, “I was kidding about the barn.”

This made no impression on Charlie.

“Does the phrase ‘No more carrots ever’ mean anything to you?”

It did not.

“Charlie! After all I’ve done for you!”

For some reason this got a response, raising the possibility that a buffalo who understands “Let’s go back to the barn” is a buffalo who understands “After all I’ve done for you”—which is to say, it raised the slim possibility that buffalo have the capacity for guilt. Charlie lowered Roger to the ground.

Roger rearranged his shorts, then spit on his hands and rubbed them together to clean off the dust from Charlie’s woolly head. Because he was a man of his word, he let Charlie graze a while longer as the sun disappeared in a tie-dyed blaze of hot pink and blue over the Jemez Mountains to the west. Then, leading him along with carrots, Roger walked him back to the barn, thinking: a few weeks ago, I was worried that he wouldn’t be able to stand up. Now he’s using me as a human dumbbell.

“Charlie,” he said when he’d gotten the buffalo back in his stall between Matt Dillon’s and Kepler’s stalls. “You know something? You’re beginning to act a little like a spoiled brat. You don’t like other buffalo. You don’t like cows. I’m not even sure you like me anymore. These walks of ours can be a pain in the butt. I need to think of ways to keep you out of trouble.”

As it happened, Charlie was about to get his first job offer. And, as hyperactive fate would have it, the offer came from some of Charles Goodnight’s old friends, the Taos Pueblo Indians.