fourteen

Until the Christmas/Farewell-to-Charlie party that Roger and Veryl had thrown in December of 2000, the couple was not aware that Taos Pueblo even owned a buffalo herd that grazed on the fenced land just outside their ancient village an hour and a half away—let alone that it had been Charles Goodnight’s gift. Dr. Marlo Goble, orthopedic surgeon/buffalo rancher par excellence, happened to mention it at the party, suggesting that they all drive up the next day to see it. Roger and Veryl, who had only recently found themselves in the buffalo-raising business and were developing a keen interest in the whole history of the animal, were amazed to know there was a herd so close by.

The day after the party, Roger, Veryl, and Marlo drove up to the reservation and met Richard Archuleta, a stocky, cheerful Taos Pueblo man in his forties with a long black ponytail. Archuleta was now in charge of the tribe’s always thriving tourism trade, but until recently he had been the buffalo herd’s manager. He walked the three visitors out to view the herd of roughly 120 head, most of them standing picturesquely in the snow, oblivious to the elements. It was a small herd, as bison herds go. Once in a while, Archuleta explained, a buffalo would be harvested and the meat given to the “traditional” Indians, but the Indians generally had little to do with them and the children only occasionally noticed them grazing in the distance.

Richard Archuleta knew a lot about the buffalo, but not where they had come from. “All I know about these bison,” he told his visitors, “is that they came from some Texas rancher.”

Roger and Veryl might have tried to look up the rancher’s name in the Taos Pueblo records, but they wouldn’t have found it there, thanks to the peculiar way the Taos Pueblo Indians kept track of things—or, rather, didn’t. Each year, a tribal governor and a war chief, as well as their staffs, are appointed by the tribal council, which consists of some fifty male elders. Each year, on January 1, when the outgoing tribal governor and war chief leave office, they box up all their records and take them away. Some say that one effect of the nineteenth-century destruction of the Indians’ culture was to leave them homeless, and one of the effects of homelessness was the feeling there was nothing left to pass on. In any case, the new administration took over each year with no record of what had happened before. Year after year this went on, the records of one year being removed in boxes to make room for the new records of the next, so that the past piled up until it was a big pile of stuff that no one recalled. It was hard enough to find out who said what at a council meeting last year, let alone learn where a bunch of bison came from a long time ago.

Veryl and Roger only learned of the origins of the Taos Pueblo herd a few months after their visit. It was then the early spring of 2001, with Charlie on the mend and almost one year old. A documentary filmmaker working on a movie about Charles Goodnight came to Santa Fe to interview Veryl Goodnight. He happened to mention that his next stop was the Goodnight herd up at Taos Pueblo.

The Goodnight herd?

“Sure,” the filmmaker said. “The herd was a gift from Goodnight just before he died. I don’t remember the details, but they’ve got letters about it at the Haley Memorial Library in Midland, Texas.”

There was something eerie about the revelation. Here they were, the parents of a handicapped buffalo who had come into their lives so Veryl could honor Charles Goodnight in her own chosen medium. Now it turned out that their house happened to be a hundred miles from a buffalo herd whose founding stock Goodnight had donated to Taos Pueblo. It was as if Charlie was opening a series of doors for them that they had no choice but to walk through.

Roger and Veryl called Richard Archuleta to tell him about Charles Goodnight’s gift and invited him down to Santa Fe to see Veryl’s files on Charles Goodnight and to meet Charlie. When Richard drove over a few days later, he parked in the driveway close to the barn and the arena and climbed out of his truck. Neither the buffalo nor Roger and Veryl were anywhere to be seen. He stood there, facing the house, wondering if perhaps he had come on the wrong day.

Roger and Veryl were actually looking out the window of the house, trying not to laugh as they watched Charlie emerge from the barn, limp up behind the unsuspecting Archuleta, and start sniffing the back of his pants.

The only time Richard—or, for that matter, most buffalo ranchers—handled buffalo was when vaccinating them in the chute or “dropping” them for butchering—or, as Richard liked to put it, “when you treat ’em and when you eat ’em.” So, naturally, he jumped when he finally sensed the animal behind him, turned, and found himself staring at a bison head.

“Whoa,” he said, staggering back a step. “Whoa there, buddy.” Charlie made a low grunt of greeting while Richard backpedaled up the walk, keeping some distance between himself and Charlie, who followed in a trot, escorting him to the front door.

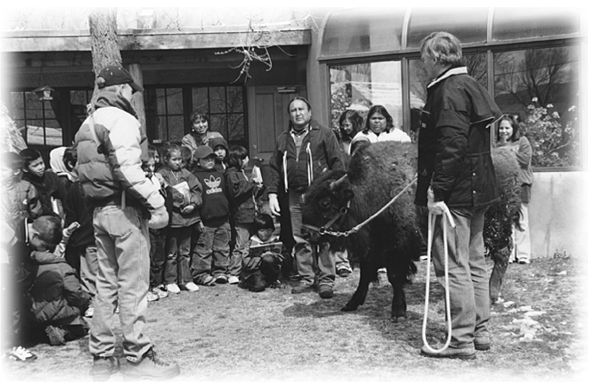

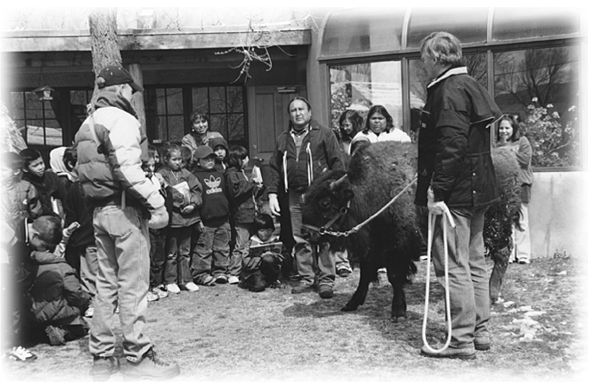

By the time Richard left that afternoon, he had gotten to know Charlie better and made him a job offer that Roger would not let him refuse: to be the most impressive show-and-tell item in grammar school history. Not long after Richard’s visit, Roger, Veryl, and Veryl’s fifteen-year-old nephew Adam Goodnight, who was visiting from Wheatland, Wyoming, loaded Charlie into the horse trailer and drove him up to the Taos Pueblo grade school. It was a blustery, overcast, late-March day, more winter than spring, when Charlie sashayed gingerly down the trailer ramp in a bright red halter, all seven hundred pounds of him, and gave several dozen Indian children their first meaningful experience with the animal that had once sustained much of their culture, and all of the Great Plains Indian culture. Charlie may not have been a buffalo to himself, but he certainly was to the schoolchildren, who had never been this close to one before.

Adam Goodnight helped herd the children into a semicircle in the yard of the one-story school. Roger, holding Charlie loosely by a rope lead just a few feet from the children, told them the story of Charles Goodnight and how he gave the Taos Pueblo Indians their herd and how Charlie got his name—and even how he got his limp. Then he asked if any of the children wanted to pet Charlie. Charlie was only a little taller than a third grader at this stage, but his horns had grown to about six inches and a few of the children thought better of Roger’s invitation. However, a handful of kids inched forward in their purple sweatshirts and turquoise parkas to touch their first buffalo, just a quick poke or a pat. Charlie stood there patiently, as if he had been doing it his whole life.

A Taos Pueblo elder, his face furrowed with age, sidled up to Roger. “I remember the bison arriving when I was a little boy. They came in on a convoy of trucks.”

“You remember?” Roger said. “You must have been a very little boy.”

“I was, but it was a big, big event. It had been three generations since most of my people had seen a buffalo. Many people had tears in their eyes.”

So the thread had not been completely broken. The gift had remained alive, if only in one man’s memory, as though waiting for Charlie, Roger, and Veryl to breathe new life into it.

“Why don’t the rest of your people know about Goodnight’s gift?” Roger asked. “Why don’t you tell them?”

The elder waved the question away. “The young people don’t care,” he said. “They don’t need the buffalo. They’ve got Wal-Mart.”

Not far away, Veryl was standing with her nephew Adam, who was still directing grammar-school traffic near Charlie, when one of the schoolteachers approached with her arm around a shy Taos Pueblo boy from the class, about seven or eight.

“This is Sonny,” the teacher said to Adam. “He thinks you two might be related.”

Since Adam Goodnight, with his blond hair and blue eyes, could not have looked more different from Sonny, Adam and Veryl at first thought it was a joke.

But the teacher was dead serious. “A long time ago, some of our people decided to call themselves Goodnight in honor of your ancestor,” she said. “Sonny Goodnight here is the great-grandson of one of them.”

“Cool,” Adam Goodnight said, holding out his hand.

“Cool,” Sonny Goodnight replied, shaking it.

And the two boys looked at each other across a chasm of history, connected only by the silent heritage of a name.