seventeen

It’s hard to keep some things secret, especially something as big as a buffalo. By the time Charlie turned two, word had started to leak out that a sculptor and a retired airline pilot a few miles outside Santa Fe had a very friendly 1,300-pound pet. So it wasn’t surprising that, on April 3, 2002, the New Mexican, a local newspaper, carried a short article titled “Only in Santa Fe: He’s a Nice Pet Buffalo, But Watch the Tongue.”

It was surprising, however, that a red-haired Santa Fe animal chiropractor named Sherry Gaber read it. She rarely read the local paper. She was normally too busy treating dogs, cats, birds, and a growing number of lame and hobbled horses. The fact that she just happened to pick up the newspaper that day was, in her mind, one of those examples of the working of some larger force, a force that had appeared now and then throughout her life.

Growing up in Skokie, Illinois, in the 1950s, Sherry had been one of those girls always trying to help sick birds and dogs. She came by her passion for healing honestly, since both her father and brother were chiropractors. Sherry would drag sick animals home to her father, who had no idea what to do with the parakeets, but tried his best to help the dogs. One dog she brought to him suffered from paralysis of the tongue, unable to eat or drink. When Sherry’s father was through moving the animal’s spine around to relieve the pressure on some of his nerves, Sherry put a bowl of water in front of the dog and he began lapping it up immediately.

Impressed that so little effort could make such a big difference, Sherry decided to become a veterinarian when she grew up. However, she quickly abandoned her ambition when she learned that it would require her to give animals injections and pills. Sherry had grown up in a medically avant garde family whose members had never been given a shot or taken a pill, and she had a strong aversion to both. She concluded that it made more sense to think about being a chiropractor for animals. But she was only in seventh grade, and one thing led to another, and she forgot about helping animals altogether. Instead, after high school she went off to Palmer College of Chiropractic in Davenport, Iowa, the most famous school of its kind, to become a healer of people like her father and brother before her.

Right before graduation, she broke up with her fiancé. She jogged to a Davenport park and sat down by a lagoon to contemplate her future. There, a strange occurrence reminded her of her forsaken destiny. She looked over and saw a squirrel lying on the ground, apparently paralyzed, able to move only its head. Since the vast majority of people on the planet live their entire lives without seeing a paralyzed squirrel, or even one that’s having trouble getting around, it seemed like a sign to Sherry. She wanted to help the squirrel, but she had no experience with animals, so she went off to get a friend for moral support and returned determined to do something. Gingerly, she approached the frightened animal and ran her hand up and down its spine. How strange to feel a squirrel! The first vertebra of the neck, called the atlas, was dislocated. With her finger, she guided it back into place.

But the squirrel didn’t move. It lay motionless on the ground for fifteen minutes. Sherry looked disappointedly at it, then settled in with her friend by the lagoon and talked for a while. Fifteen minutes later and without any preliminaries, the squirrel shot to its feet and disappeared up a nearby tree, leaving Sherry far below, staring in utter amazement at what she seemed to have done after all.

Years later, Sherry would look back on this moment and be amused that she hadn’t paid more attention to the sign. Of course, by then Sherry had learned what most adults know: that in hindsight the road is always littered with unread or poorly heeded signs. For Sherry, the squirrel had been like an easily ignored tap on the shoulder. She soon forgot about it and moved back to Chicago to start a practice helping people. For many years, she treated all kinds of physical problems until one day she began to feel troubled, as though something in her soul was out of alignment. She wasn’t enjoying her work nearly as much as she used to and wondered if there was something else she might do with her life.

Around this time, out of the blue, some of her human patients began asking her to look at their ailing pets. More signs. They brought them in after hours—limping dogs, listless cats, petulant parrots. One night, Sherry bent over a sick cat a patient had brought in. As she always did before administering treatment, she muttered the silent prayer, “May the greatest good be done.” As she prepared to go to work, the next sign hit Sherry right between the eyes. In the corner of the room Sherry saw a tall figure, a transparent silhouette that appeared to be made out of magenta fluorescent light, all head and neck and shoulders. She had never had a vision before, and she was frightened enough that she was glad to hear the voice of the cat’s owner saying, “Do you think Herc will be all right?” Well, Sherry thought, at least I’m not dead. The cat’s owner seemed completely unaware that they were sharing the room with a huge magenta woman. In her panic, Sherry was about to ask the woman if she could see the silhouette, but when she glanced back the silhouette was gone. Utterly and completely gone.

Sherry sold her practice and went to work as a volunteer, cleaning cages at a veterinary clinic in Chicago. She did that for ten months without being able to truly decide what to do next with her life. Apparently, it was going to take more than a paralyzed squirrel and a huge fluorescent figure to help her make up her mind.

It was going to take a dog with irritable bowel syndrome. The clinic secretary’s dog was suffering from it and had already undergone a painful treatment that hadn’t helped. The secretary was distraught. Sherry offered to help. She adjusted the dog’s spine and the problem went away and never came back. Then the clinic’s veterinarian himself came to Sherry and asked if she could work on his dog, who had been having epileptic seizures. The seizures stopped for a year, and shortly thereafter Sherry enrolled in the American Veterinarian Chiropractic Association’s school.

With her degree, she opened an animal chiropractic practice on Chicago’s North Side, working mostly on dogs, cats, and the occasional lame horse. But she was growing tired of Chicago winters and felt drawn to Santa Fe. In 1990, she and her new husband, a recently retired financial consultant, eloped to a seven-thousand-foot high valley in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Her card read: DR. SHERRY D. GABER, DOCTOR OF CHIROPRACTIC, CERTIFIED IN ANIMAL CHIROPRACTIC, FELINE–CANINE–EQUINE–AVIARY.

She and Steve had been in Santa Fe for a dozen years when she read the newspaper article describing Charlie’s accident and miraculous recovery. The piece mentioned a lingering limp and other problems that Sherry could diagnose from a distance as symptoms of a displaced atlas. Sherry got Roger’s phone number from the newspaper reporter and called.

“I just read that article about your buffalo,” Sherry told Roger. “I’m a large-mammal chiropractor and I’d love to take a look at him.”

Sherry braced herself for Roger’s response. She was well aware that a cold call from a stranger promising to correct your buffalo’s posture was not an everyday occurrence. She didn’t know that Roger Brooks’s buffalo had already enjoyed the benefits of acupuncture at Colorado State University.

“Free initial consultation,” she added.

“Well, I’m willing to try anything that might improve his health. Come on over.”

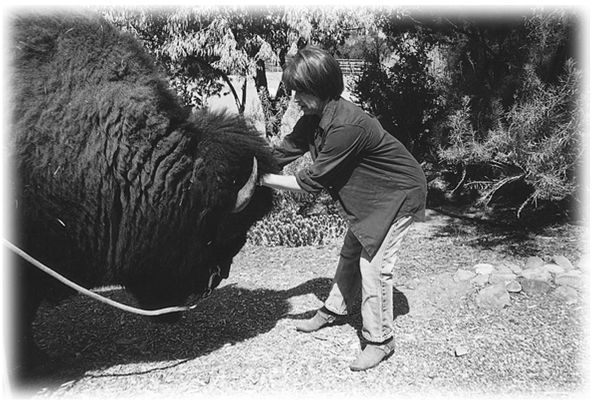

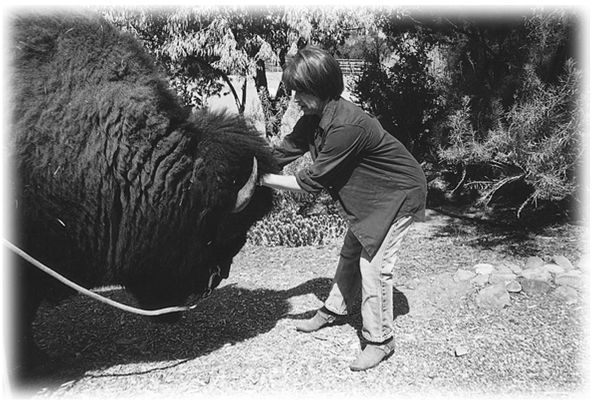

Sherry drove the five miles from her house to theirs. As Roger recounted Charlie’s case history to her, Sherry watched Charlie patrol his pen.

“See that leg?” Roger said, “He has trouble going uphill and down. And he refuses to go in a circle.”

She could see how Charlie held his head tilted to one side and favored his right hind leg. She saw how hard and thin his muscles had become up and down his right side. She could see that his spine was out of alignment.

“I think I can help,” she said. Those were the same words she had used fourteen years before with the owner of the dog with irritable bowel syndrome. But Sherry felt she needed to bone up on buffalo anatomy before going to work on Charlie, so Roger gave her the phone number of Dr. Rob Callan up in Colorado, who was glad to send Sherry pictures of a buffalo skeleton. Sherry studied the pictures at home and returned to see Charlie a few days later. This time, Sherry was a little bit nervous. She knew that a buffalo was likely to give her only one chance to adjust his spine.

Sherry climbed on a big Igloo cooler to give her some height and Roger called Charlie over to the fence.

“C’mon, Charlie, c’mon, son,” Roger said. “Got a new friend to see you.”

As Charlie turned and lumbered toward them, Sherry thought there was almost something silly about him with his shaggy beard and thick thatch of hair, somewhere between an Afro and a Beatles cut. If he were human and this were high school, she thought, he’d be the overweight but cute guy who gets A’s in Chem and plays tuba in the band.

“I’ve got to warn you, Sherry,” Roger said with a little laugh, “that he’s going to want to smell your crotch, but don’t worry. It’ll keep him interested and quiet for a few minutes and—who knows?—you might even like it.”

“I’ve been around big animals before,” she assured him.

Right on cue, Charlie’s head, larger than Sherry thought it was possible for a head to be, emerged magnificently through the fence. His nose found Sherry’s crotch and he began to sniff avidly.

With no time to lose, Sherry bent forward at the waist, reached as far forward as she could, and plunged her hands into the heavy coat on the back of Charlie’s neck. Within seconds, she found what she had suspected from reading the newspaper article.

“His atlas vertebra is displaced,” Sherry said. “It’s interfering with his lateral spinocerebellar tract.”

“Come again?”

“The lateral spinocerebellar nerve tract is the nerve on the side of the spinal cord that enables the brain to be aware of the different parts of the body. If Charlie’s brain can’t perceive his right hind leg, it won’t send motor impulses down there to move it. Hold on—I’m about to adjust it. First I like to say a little prayer.”

Sherry closed her eyes and prayed quickly for the greatest good to be done, adding a special prayer that Charlie stop drooling on her jeans.

She pushed Charlie’s atlas partway back into place. Charlie backpedaled a few steps, paused, then moved forward again, settling his nose again between Sherry’s legs. “Good boy,” she whispered, then said to Roger, “He knows I’m trying to help.” Again she pushed on his vertebra and it gave a little more beneath the pressure of her fingers. Charlie stepped back again, grunted this time, and again he returned to the fence. This time, as she worked on him, he dropped his head, as if he was relaxing into it. Animals would settle like that, once you’d alleviated some of their discomfort.

“That’s a good boy,” Sherry said.

After each little adjustment, he backed up and returned, until Sherry had manipulated the wayward vertebra back into perfect alignment with the rest of his spine. This time, Charlie backed up but didn’t come forward.

“It’s all about their pain level,” she said to Roger. “He knows I’ve done what I came to do. He can feel it. He already seems to be walking a little better.”

It was true. And Roger wanted to say, “Sherry, where were you a year and a half ago?” If Sherry had come into Charlie’s life soon after the accident, who knew how much further along he would be? For all that Colorado State University’s School of Veterinary Medicine had done, and it had been a lot, including acupuncture, no one had suggested chiropractic. If, if, if.

“Look at that, will you?” Sherry said. To prove his renewed vitality, Charlie had trotted to the far end of the arena and begun attacking his plastic drum. He gored it with a horn and threw it triumphantly into the air.