eighteen

Up in Yellowstone, there was no solution in sight. The Buffalo Field Campaign activists were dug in, denying the reality of the brucellosis threat entirely and rejecting the idea of vaccinating wild buffalo—for which a bison-specific vaccine didn’t yet exist, anyway—in favor of simply vaccinating Montana cattle. The BFC called for the opening of federal lands outside the park to the buffalo. They sought to have the buffalo added to the list of endangered species. All in all, the group was charging hard against the entrenched interests and mythology of the American West. The Montana Department of Livestock and other state and federal agencies sought to reduce the risk of brucellosis to that elusive zero, and they were making the Yellowstone buffalo pay the price while they tried. It was a good old standoff, and more and more reporters and op-ed writers were taking notice. Meanwhile, over the winter of 2002–3, 246 more Yellowstone buffalo were shot or captured and sent to slaughter.

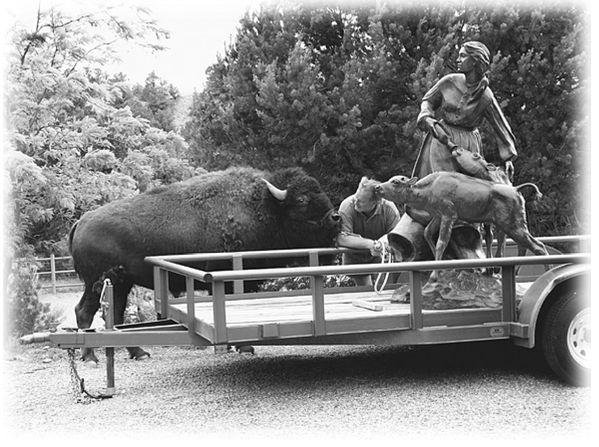

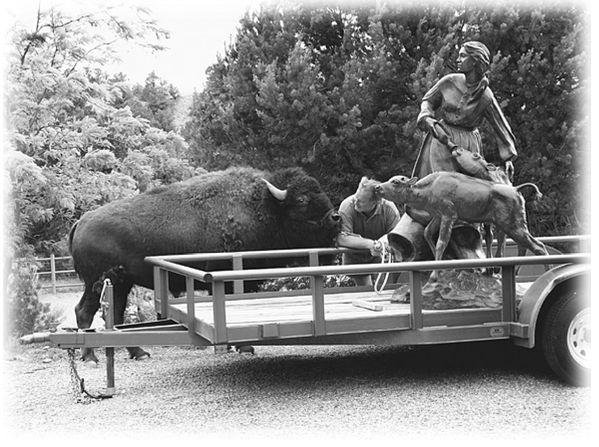

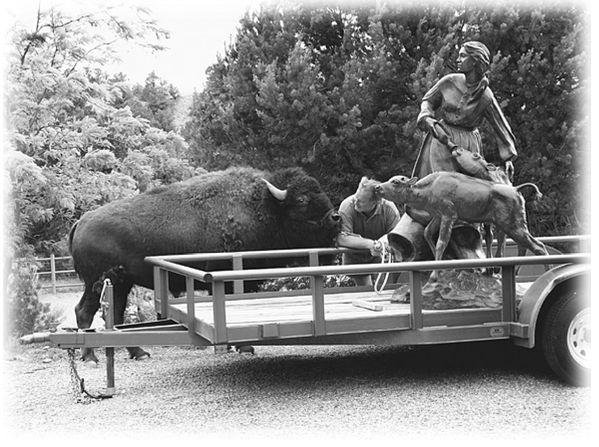

In Santa Fe, Charlie, now 1,800 pounds and still growing, “modeled” for Veryl’s fourth sculpture of him, “Prairie Contender.” Charlie’s uncertainty at the age of one had been replaced by determination. His tail was still up, but instead of wearing an expression that mixed fear and wonder, Charlie held his head low, sniffing the air, perhaps getting a whiff of predator or of the estrogen-heavy odor of a rutting cow.

In the spring of 2003, President Bush invaded Iraq and Charlie turned three.

Charlie had not been for a hike with Roger for the last year, and his life had settled into a slower, safer status quo. He spent all his time in his stall or in the arena. Except when he was out of town, Roger spent an average of an hour a day with him—feeding and grooming him, mucking his stall, but most of all working with him to strengthen his legs. He used carrots to entice him into jogs around the arena. He helped Charlie work on his cantering. He made sure Charlie got in a good sparring match with his barrel. The important thing was to be there every day, to have continuity of contact; otherwise, Roger knew he would lose his relationship with Charlie, the one he had painstakingly created, one unlike any man-buffalo relationship in history. Roger never forgot for a minute that Charlie was and always would be a wild animal, from his first breath to his last, and that if their trust was broken, it could never be mended.

An hour a day with Charlie was a lot of time, considering how busy Roger was with Veryl’s flourishing art business, his soccer games, his reading, keeping up with his old friends in the intelligence community, and running a rather complicated household that had its own payroll. Veryl complained that he never rode Kepler anymore, his horse for twenty-three years; that it wasn’t fair to Kepler. Roger would say, “Well, you’re right, honey, but I don’t have any more extra time, and Charlie needs it more.”

Although Charlie was still at times fussy about being touched on the head and horns, and although you wouldn’t want to leave your worst enemy alone in the arena with Charlie, Roger began to notice a mellowing in the buffalo, and he decided in March that it was safe to lift the embargo on long walks in the foothills behind the house. Roger was suddenly looking forward to hiking with him, the way the parent of a nineteen-year-old son might be delighted at the thought of having a civil conversation with him now that he’d survived the teenage years and no longer believed he knew everything.

As Veryl videotaped the hike, Roger led Charlie over the crest of a foothill, where they stopped, their outlines crisp against the hard blue sky. Charlie’s hump now came up to Roger’s head. Suddenly, Charlie, perhaps overjoyed himself to be out and about again, started licking Roger’s face. Roger mugged to Veryl and the camera: “If I’m not faithful to you, it won’t be on purpose.” Traversing a gently inclined hill, Charlie was surefooted, although his gait was still not normal.

“His legs aren’t injured,” he explained to friends who had accompanied them on the hike. “It’s all in his neck. He was getting pressure on his spinal cord from his out-of-alignment vertebra. But, see, by doing this—the walk, and I jog with him and chase him around the arena—it’s going to get his brain working his legs better and it will strengthen up his right hind leg, and once he can push off evenly, he’ll improve dramatically.”

The walk ended with Roger sitting on a lawn chair and stroking Charlie’s head, which was bigger now than Roger’s head and torso put together. Mellowed by the walk, Charlie was enjoying this bit of intimacy. Although his horns were mere inches from Roger’s face, Roger was as relaxed as if he were petting one of their dogs, but he was thinking: a buffalo dropped into my life three years ago and it has never been the same.

IN 1983, Lewis Hyde, a thirty-eight-year-old poet, essayist, teacher, and sometime carpenter and electrician living in Watertown, Massachusetts, published a book he’d been laboring on for five years called The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. It is not an easy read, combining anthropology, economics, literary criticism, psychology, and social history. Its index includes entries for Maori hunting rituals, Harold Pinter, property rights in organ transplants, Ezra Pound’s credit theories, and McDonald’s.

Like the kind of gift the book is a study of—a “transforma-tive” gift that has “the power to awaken a part of the soul”—the book has circulated in a community of thoughtful readers for more than two decades.

The Gift is not your ordinary fare and neither are people’s reactions to it. The reader reviews posted on

Amazon.com are a good example. “Why isn’t this a classic?” a reader from Calgary complains. “The first essay in this compilation of three is one of those pieces that can potentially change a person’s life,” writes another from Concord, Massachusetts. And a reader from Kentwood, Michigan, adds: “I would rank this book in the ten most important I have read. His study of gift-giving throughout history and with different cultures changed my entire view of how we give and receive gifts.”

One of the The Gift’s fans was Charles Goodnight’s great-grandnephew Andy Wilkinson, who had sung at the going-away party for Charlie. A poet friend of his had suggested he read the book at a point in Andy’s life when he was grappling with the distinction between art and commerce, and not merely in an academic way. For five years, writing and performing had been his full-time occupation—the kind of occupation that can make a person keenly aware of the difference between art and commerce. In an upper-level seminar he taught as an assistant adjunct professor in the Honors College at Texas Tech in Lubbock, he began using the book to teach that creativity was a gift. Because a gift possessed worth—was not a commodity with mere monetary value—people should not expect compensation for its fruits, he taught. Gifts, as Lewis Hyde makes clear, operate in a different and vastly more spiritual economy than the usual goods and services. Andy Wilkinson figured that teaching a bit of Lewis Hyde’s book might save artists and aspiring artists a lot of grief in their lives.

Charlie had many of the attributes of a gift, as described by Hyde. A gift cannot be bought or acquired through an act of will. A gift is never used up, no matter how much it’s used. The giving of a gift establishes a personal relationship between the parties involved. The gift must always move—as illustrated in many folk tales in which the gift dies because one person tries to hold on to it. A gift’s movement, when it circulates, is beyond the control of any person, and it moves toward the person who needs it most. Hyde also writes about how gifts—whether a cheap but cherished object passed around by sorority sisters, a Mozart symphony shared by millions, or the battered silver Stanley Cup that passes each year to the National Hockey League’s championship team—create and maintain “institutions of positive reciprocity.” Without these institutions, people become disconnected and, in Hyde’s words, “are unable to enter gracefully into nature, unable to draw community out of the mass, and, finally, unable to receive, contribute toward, and pass along the collective treasures we refer to as culture and tradition.”

Andy Wilkinson, who among other things was a student of the Plains Indians and of his own great-grand uncle Charles Goodnight, was a person who deeply understood that for the Indians the buffalo had been, for thousands of years, a gift—a gift of nature, of the Great Spirit, without which they could not survive. Indians in southern Canada thought the buffalo were a gift that came from under a lake in modern-day Saskatchewan. Many Plains Indian tribes believed that buffalo came from a big underground cave in northwest Texas, and that each spring the Great Spirit arranged for an endless supply of buffalo to pour forth. In his 1877 book The Plains of the Great West, Colonel Richard Dodge—the same man who once said that every buffalo gone was an Indian gone—wrote of more than one Indian who claimed to have actually seen the animals streaming out of the cave.

The Indians did not think of themselves as bigger or smarter than the buffalo. They did not regard the buffalo as being in the least subject to their will. As the Lakota medicine man John Lame Deer has written about the buffalo, “They have the power and the wisdom. He is our brother. We have many legends of buffalo changing themselves into men. And the Indians are built like buffalo, too—big shoulders, narrow hips.” This echoes a passage in Lewis Hyde’s book, that “. . . we cannot receive the gift until we can meet it as an equal. We therefore submit ourselves to the labor of becoming like the gift.”

These ideas—that we can learn from animals, that they are in many ways our equals and our superiors, that becoming more like an animal is something to strive for—are open to ridicule and often lost to us now in the “civilized” world. But, for the Indian, the buffalo was sacred. “That animal,” Lame Deer writes, “was almost like a part of ourselves, part of our souls.... It was hard to say where the animal ended and the man began.” To kill a buffalo, then, was no simple matter, as Lame Deer explains:

When we killed a buffalo, we knew what we were doing. We apologized to his spirit, tried to make him understand why we did it, honoring with a prayer the bones of those who gave their flesh to keep us alive, praying for their return, praying for the life of our brothers, the buffalo nation, as well as for our own people.

To the Indian the buffalo was a gift, but to the whites the buffalo, along with its hide, its tongue, and its bones, became a commodity. “That terrible arrogance of the white man,” Lame Deer wrote, “making himself something more than God, more than nature.” To understand this was to begin to appreciate that the Great Slaughter did not just eventually deprive the Indians of material self-sufficiency, but also violated the spiritual economy in which the buffalo was the currency.

In this light, it was possible to see Charlie as a gift sent by Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight and Standing Deer into the present. Of course, this isn’t much different from saying that a new puppy has a way of bringing family members together, of increasing their humanity, of restoring some of life’s mystery by pointing out a world of feelings and connectivity that exists apart from the human language that often weighs down every human transaction. Except that in Charlie’s case, the family was much bigger, the message much larger, and the present stakes significant. If he was a gift, he had been sent so that Veryl could honor her ancestors and the memory of all buffalo, so that the Taos Pueblo adults and schoolchildren could be reconnected to the meaning of their buffalo. He had come to bring together two young Goodnights, Adam and Sonny, and honor the white man who honored the Indians. It was as if this gentle, wounded buffalo had been sent out among the people so that they could see and touch and smell a world that had been left behind. So that they might “enter gracefully into nature.”

Charlie was like a piece of the past that must be dealt with before you can move on.