nineteen

Before Roger could move on, he wanted to make one more attempt to persuade the Taos Pueblo Indians to return a few of their buffalo cows to the purebred descendants of Charles Goodnight’s original herd, still living in Texas, and help diversify the gene pool. It had now been almost two years since his first visit to the war chief with Richard Archuleta and their unsuccessful attempt to broker a deal. Among the gifts that Charlie had given Roger were a heart-wrenching awareness of the great injustices done to the buffalo, and a commitment to help restore the animal to its proper place on the land and in the American imagination. In the summer of 2003, the time had come again to pay the Taos Pueblo officials a visit.

Once again, he asked Richard Archuleta to make the arrangements. In July, Roger drove north into Taos to meet Richard Archuleta at a restaurant called Michael’s for a cup of coffee and a piece of homemade pie before heading up to Taos Pueblo, just outside of town. When Roger walked into the cafe, Richard was in his usual buoyant mood. Roger was contemplative. The prospect of a meeting with the new war chief didn’t thrill him. To call the previous war chief “unresponsive” would be an understatement.

A little before three in the afternoon, Richard ushered Roger into the nondescript tribal government office building on the fringes of the picturesque reservation. Although Richard had made an appointment, the receptionist told the two men that the war chief wasn’t in, but would try to find him. Roger rolled his eyes. Richard showed Roger into the conference room at the end of the hall and then disappeared for a few minutes. Roger sat waiting in a chair while a stuffed buffalo bull’s head glowered at him from the opposite wall. Roger waited. It was so frustrating. Yes, he was a white man asking them for a favor, but it was a favor to the buffalo, a favor to themselves, really. Closing the circle of Charles Goodnight’s generosity by making a few buffalo available to the man’s original herd made sense in every possible way. What was the problem?

The conference door opened and Richard showed in two casually dressed Taos Pueblo men in their forties. Neither of them was the war chief. Vernon Brown was the lieutenant war chief; Louis Zamora was an aide. Everyone shook hands, Richard Archuleta excused himself, and the three men sat down at the table, Roger across from Louis, who sat right under the buffalo head, while Vernon settled at the end of the long table.

Roger fought off a creeping feeling of futility and placed his large freckled hands flat on the Formica conference tabletop. “My wife is a sculptor,” he began in the slightly mechanical voice of a salesman on his last call of the day. “We live in Tesuque just outside of Santa Fe. Her ancestors, Charles Goodnight and his wife, as you probably know, salvaged some buffalo calves in the 1870s, bottle-fed them, and started a herd that exists to this day in the Palo Duro Canyon. So my wife could make a sculpture in their honor, we got a bottle baby ourselves to model for her, and right now he’s three years old and still lives with us.

“Right before Goodnight died, he gave your people some of his pure buffalo as a gift, because of his long friendship with Standing Deer, and because, after the Great Slaughter, it was hard to get hold of the buffalo tallow your people needed for their traditional ceremonies.”

“We’re familiar with the story,” Vernon Brown interjected.

Well, that was something, Roger thought—maybe there’d been some kind of carryover from two years ago. “Now there’s no official record of the transaction because Goodnight gave the buffalo, not sold them,” he said. “But we have documentation, letters which we gave to Chief Romero two years ago, but which apparently no one can find.”

“They’re probably in a drawer somewhere in his house,” Vernon said with a faint smile.

“Probably,” Roger said with a rueful chuckle. “So the rest of the herd lived wild in the Palo Duro, from Goodnight’s death in 1929 until 1997, when the State of Texas rounded them up and gave them a fenced-in home in Caprock Canyons State Park. They blood-tested all of them and extracted any that had cattle genes, so they’re left with thirty-six pure descendents of the Southern herd. But they need new pure blood. And that’s where your herd here comes in. Your herd has already been tested at Texas A&M. Your bison are a match.” Roger then quickly added, in case the meaning of it all hadn’t come through: “Goodnight, who was a friend of the Taos Pueblo Indians for a long time, came to funerals here and gave your people the bison when he was no longer a rich man. Now we hope you’ll commemorate his legacy, his herd, by coming full circle and making a few buffalo available to the State of Texas.”

Louis Zamora, who could have posed for the buffalo nickel with his aquiline nose and black hair pulled back in a ponytail, asked, “Do you represent the State of Texas?”

“No, I don’t represent anybody. I’m not officially connected, although I have spoken with Danny Swepston, the chief biologist for the state parks and wildlife district.”

Vernon turned to Louis. “Louis, I think we better get with these people and sell some of our old cows to them. The ones who are six to ten years old, ’cause we can’t use them when they die of old age.” He turned now to Roger. “What would we get in return? Cows or bulls?”

Although he had been thinking more of a donation than a trade, Roger was encouraged that they had come this far. “A trade,” Roger said. “That’s an idea.”

“No trade,” Louis said. “They’ll need to purchase them. We’ll need to get paid.”

“Later, maybe we can trade,” said Vernon.

All right, Roger thought—let’s just move it ahead. On the other hand, he knew what it was like getting an appropriation from the government, even just a few grand for some buffalo. It could take forever. That would be a very sad irony indeed if the Taos Pueblo Indians were ready to do the deal, but the state couldn’t find the dough. Roger would have to think about how to finesse it.

“They’ve got to be DNA-tested and healthy, though,” Roger said, adding, “I’ll be happy to step aside and let this thing happen.” He didn’t want to saddle the deal with himself; it was their circle to complete.

“No, no,” Louis protested. “We want you to be part of it. You already know this Swepston fellow.”

“We might even want to go see this herd,” Vernon suggested.

“No problem,” Roger said. In the other meeting, there had been this static of fear and resentment in the air—the interference caused by two hundred years of violence and indifference. Now it felt like they were all on the same side. It was a little too good to be true. “That would be great if you went to Texas to see the herd. You could visit the Haley Memorial Library in Midland as well, which has all Goodnight’s papers. I should have remembered to bring copies of those letters with me today—the ones from your War Captain Lujan back in ’twenty-nine, thanking Goodnight for the buffalo.”

Vernon turned and addressed Louis. “We need to set up a time frame to do it all before December. Before the administration changes.” He flashed a knowing smile.

“That would be great,” Roger said. It would be more than great. It was absolutely necessary. If they didn’t get it done by December, it would be as if this meeting had never taken place at all.

On his way back to Santa Fe, Roger met his old friend John Painter for a drink at a restaurant in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Moutains outside of Taos. Its patio, ringed by a low white stucco wall, had a spectacular view of the valley and the Taos Gorge, along which Charles Goodnight had traveled 150 years earlier to meet Standing Deer for the first time. As the day cooled, the two men sat with their margaritas and watched the sun make its way down the sky.

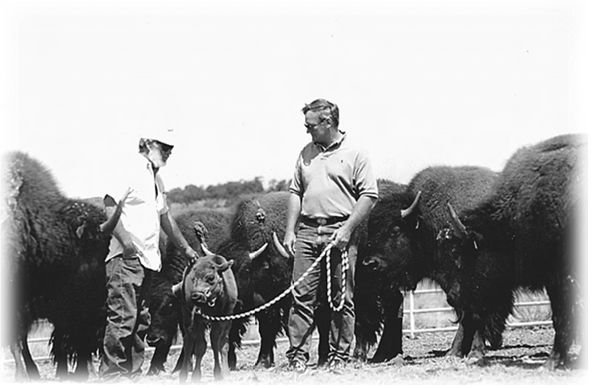

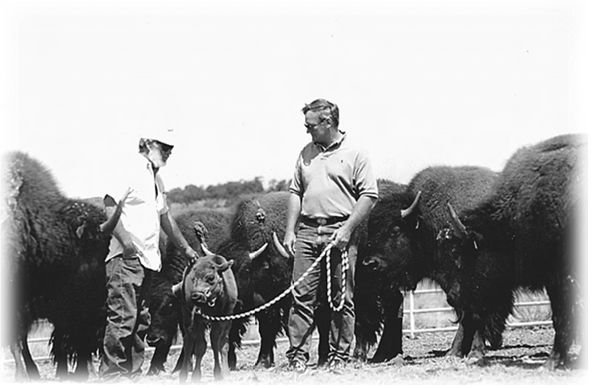

“Remember the time I was visiting you with Charlie,” Roger said, “and we were out in your pasture with the buffalo and the calves?”

“And Charlie had no interest in them, but one of my cows was making a troubling noise,” John remembered.

“Which I noticed. She was about fifteen feet away, looking menacingly at us, and I said, ‘Let me know if we’re in trouble,’ and you said, ‘Roger, we’ve been in trouble for quite a while.’”

They both laughed and sipped their drinks. “So how is he?” John asked.

“Charlie couldn’t be better.”

“I don’t think he’ll get more aggressive at this point—that’s one thing you don’t have to worry about. He’s a pretty mellow guy. Probably the mellowest bison in the history of the planet.”

“I want you to look after him if I die before you, John.”

“What?”

Roger put his margarita down and looked John in the eye. “It’s the real reason I wanted to meet you for a drink. I wanted to look you in the eye and ask you to take care of him if something happens.”

“Well, I’d be honored.”

“Veryl can’t handle him alone.”

“I know that.”

“There’s no one else to do it. There’s nothing more precious to me in this world, except Veryl.” Roger quickly looked away toward the setting sun, bisected now by the black serrated profile of the mountains. He knew John was one of the few people who could understand that the living thing he loved second most in the world was a lame buffalo.

“I’ll give him his own corral”—John too was in silhouette now—“and I’ll go out there every day and we’ll reminisce about what a great guy you were.”

“Not so fast,” Roger said, enjoying John, the sunset, the drink, his meeting with the Taos Pueblo Indians, the unexpected richness of it all. “I’m not going anywhere yet.”

“I sure as hell hope not.”

“But I won’t last as long as Charlie.”