twenty

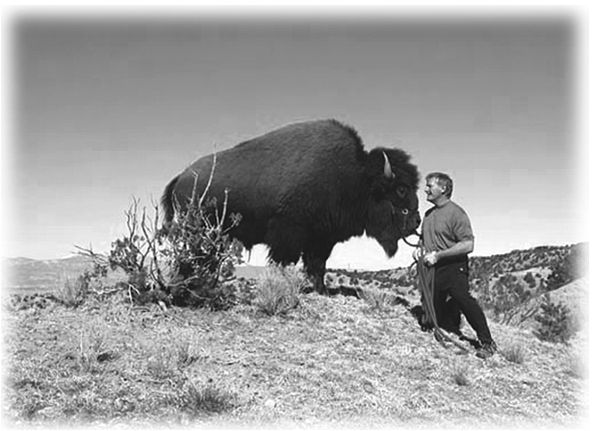

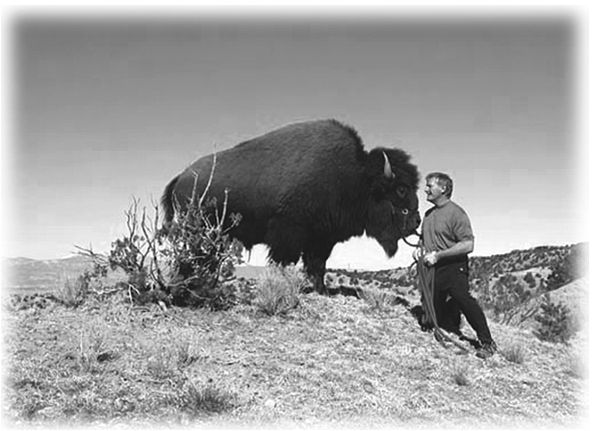

In mid-July 2003, while Veryl was on a weeklong painting trip in the Rocky Mountains with some other artists, Roger went out to the arena to take Charlie for a hike.

As Roger approached the large rectangular arena, he didn’t see Charlie right away and assumed he’d gone back to his stall. As he changed his course slightly, heading for the barn, he heard a low grumble and lifted his head. At the far end of the arena, Charlie was lying on his left side near the fence with all four legs off the ground. Roger hopped into the arena and raced to him. As he got closer, he could see that Charlie was terrified, unable to get up. In his struggles, he had kicked down part of the fence. Blood was caked in one nostril. All Roger could surmise was that he had caught his head in the fence, twisted his neck, reinjured his spine, and the pain or a muscle spasm was immobilizing him. He couldn’t throw his head to the right, which meant he couldn’t initiate the process of getting up. Now he lay helplessly on his side, his all-too-human right eye looking plaintively at Roger.

“Stay right there, Charlie,” Roger said, his heart pounding. “I’ve got an idea.” He went to the barn and returned with a break bar, six feet and fifty pounds of iron used for breaking up asphalt. He slipped one end of it under Charlie’s neck and with both hands on the other pushed as hard as he could. If he could only leverage Charlie’s head a foot or so off the ground, it might be enough for Charlie to get his legs under him. However, the only thing that moved was the break bar itself, which, unbelievably, bent under the strain.

Roger ran to the house, called the fire department from his office, and asked the dispatcher to send some men out to help him raise a hurt buffalo.

“I’m afraid that’s not the kind of thing we do.”

“Ma’am, I’ve got a very tame buffalo with an injured neck and if I don’t get him up on his feet soon, the shame of it, if not the pain, is going to kill him.”

“I’m sorry, sir. I can’t dispatch firefighters to your house just because your buffalo is hurt. If I did that every time someone called with a hurt buffalo—”

“What do you mean, every time? When did you ever get a call from someone with a buffalo before? This is an emergency, ma’am.”

“Maybe you should call a vet.”

“I don’t need a vet right now. I need four strong men.”

“Why don’t you call some friends?”

“If I had four strong friends lying around, do you think I’d be calling you? Now, look, I’ve got a three-year-old buffalo here who’s almost a member of the family, he’s hurt, and I need to get him up.”

“I’m very sorry, sir.”

“Ma’am, has your department ever rescued a kitten from a tree?”

“I believe so.”

“I rest my case.”

“I’m sorry, sir?”

Roger slammed down the phone and ran out the door to the arena again, where Charlie still lay on his side, as helpless as a beached whale, nostrils dilating, kicking at the air futilely. In the barn, Kepler whinnied. Roger knelt by Charlie’s side, soothing him.

“It’s all right,” he said, stroking his muzzle. “We’ll get you back on your feet. Hang in there.”

Charlie grunted. After three years, Roger could distinguish the slightest gradation of meaning in Charlie’s grunts. The sound he made now was a heart-rending plea for help. Roger did the only thing he could think of—he ran back into the house and called the fire department again.

“I’ve got smoke in the house,” he said.

“Didn’t you just call about a buffalo?”

“Yeah, but now there’s smoke in the house. I’m not sure if it’s related.”

“You’re the guy with the buffalo.”

“I’m the guy with smoke in my house coming from an unidentified source. You better send some men and a truck down here.”

There was another pause before the dispatcher said, “All right.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” Roger replied. “Thank you.”

When the three firemen arrived twenty minutes later, sirens blaring, Roger was waiting for them. They hopped off the truck and followed Roger to the scene, where the break bar and some loose boards from the barn were now lying next to Charlie. Together, the four of them tried to leverage Charlie to an upright position. Using hay bales as shims to secure their progress, they finally succeeded. Charlie was standing. Roger could see now that, in his struggles, Charlie had worn patches of hair off his flank and broken the skin in a couple of places, exposing dark red tissue underneath. But he was up.

“Thank you, gentlemen,” Roger said, walking the firemen back to their truck.

“No problem,” one of them replied, the sweat still pouring off his face. “Although you may want to consider a smaller pet.”

“He’s not a pet. He’d be with his own kind, except he’s lame and couldn’t survive in a herd.”

“So you’re stuck with him?”

“I’m not stuck in the least,” Roger said, although what he was thinking was that everyone was stuck with something or someone, but not everyone was lucky enough to be stuck with a buffalo.

After the firemen left, Roger went back and walked Charlie to his stall, then called a neighbor, a veterinarian named Tom Parker, who gave Charlie some steroids to control whatever swelling there was in his neck. Charlie seemed fine the rest of the day. The next two days passed uneventfully, although the world once again felt fragile, and all the more so since Roger couldn’t reach Veryl, who was incommunicado for several more days up in the Rockies. He fretted alone, checking on Charlie almost every hour.

Two mornings after the accident, before dawn, Roger went to the arena and found Charlie down again on his left side, bleeding from the nose. Roger pulled blood and mucus out of Charlie’s nasal passage, then called Tom Parker and two other neighbors. After they got Charlie up with the break bar and some hay bales, the vet took Roger aside.

“You need to get this animal to some place where he can be taken care of,” he said.

“I know.”

“Maybe you ought to haul him back up to CSU,” the vet said, “where you had him before.”

“That’s what I was thinking.” Sherry Gaber was in Europe and he didn’t feel he had much choice. Within two hours, he was on the road, dragging his sick buffalo behind him in an old borrowed horse trailer—Charlie had long outgrown their small one—in the direction of Colorado State University’s School of Veterinary Medicine. Nine long, lonely hours of blacktop and a lot of unanswered questions lay ahead of him. He pounded the heel of his hand against the steering wheel. He had thought they were out of the woods. Still, he felt some optimism brewing beneath his frustration. He was doing something.

The roads were bad. Nothing made you aware of it like having a hurt animal behind you. I’m on a federal highway, Roger thought, and my buffalo’s getting potholed to death. It would be nice, he thought, to have some of those billions being spent in Iraq to rebuild this country’s infrastructure. It would also be nice if their custom-made horse trailer had already come. “Hang in there, Charlie,” he yelled over his shoulder.

Somewhere between Walsenburg and Pueblo, Colorado, the city where the young Charles Goodnight had lived before heading for Texas to make his fame and fortune in the 1870s, Roger felt a little tickle in his throat. A bubble of dread was forming, threatening to close off his airway. He tried to clear it, force it up and out of his throat. He coughed over and over again. He recognized it. A little nervous retching cough. The same one he developed whenever he was about to face a combat situation for Air America. He was doing it again, for the first time in thirty-four years.

At CSU, it was 102 degrees and things were different than they had been before. At 1,800 pounds, Charlie was more than three times the size he had been on his last visit two and a half years earlier and everybody was a little afraid of him. The veterinary students who had treated him before had moved on, and the new crop, who might have been well disposed toward Charlie had they remembered him as the valiant and personable adolescent buffalo who had beaten the odds and walked out of CSU under his own steam, regarded Charlie as simply another unpredictable large mammal to look after. The staff wouldn’t enter his stall unless Roger was there, in case something happened—even though Roger knew Charlie was in no shape to hurt anybody. He was pained to see that vulnerable look in Charlie’s eyes again.

Dr. Callan loaded him up with painkillers, then examined his neck. There was obvious swelling, but no definitive diagnosis. Dr. Callan proposed operating on his neck, but that again raised the issue of the dangers of anesthesia for ruminants, and this time the situation wasn’t so dire that Roger was willing to risk it. Heroic measures did not seem required. What Charlie really needed, it dawned on Roger after a few days in Fort Collins, was Sherry Gaber.

He left CSU with a pocketful of antibiotics. Charlie stood in the trailer all the way back, 450 miles straight down Interstate 25 to Santa Fe. Roger wondered if he had accomplished anything at CSU. It was a wash, he decided; Charlie was no better, but at least he was no worse. At least he hoped not, as the trailer took another federal bump. The roads around Denver were the worst. Every flaw in the road had to be hell for Charlie.

Roger listened to Andy Wilkinson’s songs on CD and to National Public Radio. The news out of Washington and Iraq was depressing. You couldn’t blow into Iraq without an exit strategy any more than you could blow into a buffalo’s pen without one. Roger was in his late fifties now and the country didn’t seem to have changed much. He felt that it was in the hands of self-serving and arrogant ideologues with neither a respect for history nor a true regard for the future. He had been around a long time and he hadn’t met many men who could understand the great but fragile web we were all part of and wanted to help keep it together.

What Roger felt was that there had to be a better America than this one. And maybe it was that hope that helped explain his love for the crippled beast, this symbolic survivor of nineteenth-century America, in the back of his horse trailer. It was animals who kept men honest. No amount of money or flattery—or even carrots—could get an animal to be untrue to itself. The ground on which humans, who were part animal, met animals, more human than we know, was sacred. Animals taught us to love even when we couldn’t know whether we are loved back. It was there, in an animal’s heartbeat, that we could feel the pulse of something bigger than we were. There, on that ground, we could feel that we were a part of nature, not apart from it.

Roger flashed on the situation in Yellowstone again. He knew that a man who didn’t treat an animal with respect not only had no respect for nature; he had no respect for himself.

WHEN ROGER REACHED SANTA FE, he led Charlie down the ramp and let him graze for a minute. Charlie barely nibbled. The road-weary, thirsty buffalo shambled across the barn’s brick floor toward his stall. But a hoof slipped, slid, and in an instant he was down. This time, half with Roger’s help, half under his own power, Charlie managed to get to his feet. He took a few little steps and fell again just outside his stall. This time Roger was caught between Charlie and the stall wall. Roger saw it coming, couldn’t get out of the way, and stiffened to absorb the impact. He made his body as rigid as possible as almost two thousand pounds of bison crashed into him. Being 230 pounds and a black belt in karate had never come in so handy. Charlie hit him across the middle—luckily. Had he fallen against Roger’s knees, it would not have been pretty.

“That’s all right, Charlie,” he said, helping him back on his feet. “That’s okay, buddy. It’s all right.”

But it wasn’t okay. It was beginning to feel as if there was a glass partition between them, the way there is between the healthy and the sick. Though the ill remain like us in every way but their illness, they inhabit a different world, fragile and unreliable, separated from others by the immediacy of their pain and fear. To dissipate some of the strangeness, humans can acknowledge it in words. Roger and Charlie seemed to have reached the limits of their extraordinary intimacy. Moreover, Charlie wouldn’t touch his food, which meant Roger couldn’t give him the antibiotics Dr. Callan had prescribed. In his stall, Charlie lowered his head and started eating dirt. It broke Roger’s heart.

“THIS IS A LIFE-AND-DEATH SITUATION,” he told Sherry Gaber on her return from her trip. He pressed a cold pack against the bruise on his stomach. “His atlas is tipped. I don’t know what else is wrong with him, and I’m not sure they did either up at CSU, but he’s falling again, Sherry. I need you over here. Maybe he’ll listen to you.”

Sherry drove over and tried to get the angle on Charlie, his lowered head almost between her legs, her hands gently on his horns to steady him. When she got close to his atlas, he protested, tossing his head. Sherry had to let go of his horns, but she stood her ground, all five feet two inches of her, nothing between them, not even fence rails, and tried again. This time Charlie tolerated it long enough for her to get her hands on that first vertebra to make a partial adjustment. But Charlie wouldn’t allow any more. The neck was too sensitive.

“No sense pushing it,” she told Roger. “I’ll have to come back and try again later.” When she returned in a few hours, Charlie was still combative. “It’s your pal Sherry,” Roger said, trying to calm him. Sherry almost gave up, but she talked to him and, finally, she was able to get in a good adjustment. Charlie immediately calmed down and seemed better, and hope burst open in Roger like a flower.

“I don’t know what I’d do without you, Sherry,” Roger said, towering over her. He coughed. It came out with three or four little bursts, like a cold car engine turning over in January.

“What’s wrong? What’s the cough?” she asked.

“Nothing.”

Roger stayed up with Charlie in his stall until 2 A.M. that night, making sure he was comfortable, hovering anxiously, watching for signs of relapse. He stayed with Charlie in the gloom of the barn’s low lights, surrounded by darkness, with the three horses shifting and snorting in the adjacent stalls. Finally, when Charlie was fast asleep, Roger crept off to his bedroom, lonelier than ever with a sick buffalo in the barn and a wife somewhere in the Rockies. He set the alarm clock for 5 A.M.; three hours of sleep was all his conscience would agree to.

When the alarm yanked him out of sleep, he dressed and walked out into the warm, inky night. “Oh, Charlie,” he said at the door to his stall. He was down again on his side, the fourth time in eight days. At dawn, he called Tom Parker and his friend Jeff Stuermer and a college kid he knew, Shane Loretzen, and the three of them got Charlie up and sternal, but not before some mishaps. The break bar hit Stuermer in the head and Charlie grazed Roger’s pelvis with the side of his horn, leaving a bruise that wouldn’t go away for an entire year. But they finally righted him and bunkered his stall with more hay bales to prevent him from falling.

In the days that followed, Charlie’s health was up and down, but with some overall improvement. When Veryl returned from the Rockies with a dozen small landscapes and a backpack full of dirty clothes, Charlie was drinking water from his black plastic tub, but he was going two or three days without eating a thing before he’d begin picking at his hay again. He stayed on his feet, though, and he began to lose the look of vulnerability Roger had noticed since Fort Collins. The distance between the two of them was again closing. Roger, who increasingly felt that the trip up to Colorado State University had been worthless, was telling friends that Sherry had saved Charlie’s life.