twenty-one

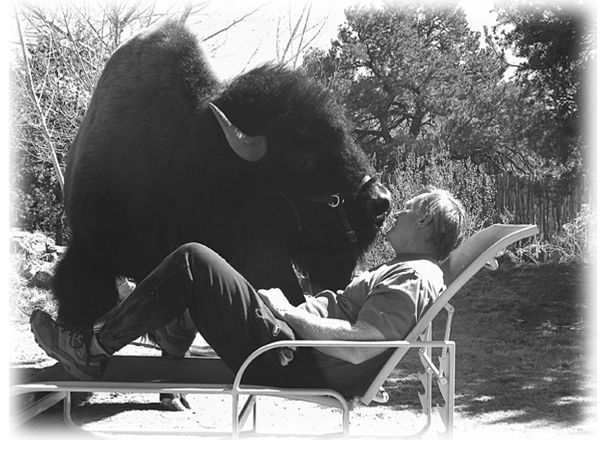

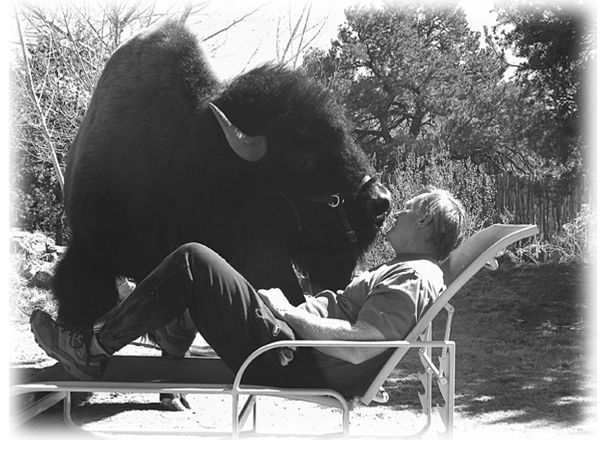

Charlie appeared to be well on the way to recovery when friends from the East came to visit at the end of July 2003. He was still off his feed, but every day he ate a little something: a bit of hay, half a carrot. The friends watched in amazement as Roger entered the stall, sat down on a bale of hay, and patted it. Charlie, who had been lying sternal, immediately got to his feet in a series of movements so quick and fluid it was easy to forget the size of the animal involved, then slowly turned in the crowded space so that he was facing Roger, his head almost touching Roger’s pants. Then, like some oversized pussycat, Charlie lowered his head and began rubbing it back and forth against Roger’s leg. The friends had never seen anything like it outside of an animated Disney movie.

The next day, Sherry came to adjust his atlas vertebra again and was pleased to find that he was holding the previous adjustment. Roger took Charlie for a short walk with Sherry around the arroyo on the perimeter of the property. As Charlie slowly zigged and zagged to inspect various vegetation, trampling a few plants in the process, the only visible sign of anything wrong with him was how he still hoisted his stiff hind right leg forward with each step. Roger explained to his friends that walking with Charlie was like walking with a two-year-old child; you had to allow for many distractions and a general disregard for anyone else’s rhythm or timetable, then take advantage of his momentary losses of interest to motivate and redirect him. Charlie occasionally needed a literal pat on the butt to get on with it. His bad leg started to look more limber, and at one point he began trotting down the arroyo, forcing Roger to jog ahead. Then he stopped for a long pee, in which he stood happily for a moment before backing up so he could smell it.

On Sunday, August 3, a couple of days after the friends left, Roger and Veryl were watching Charlie graze in the backyard through their living room window when they noticed he was breathing rapidly. It was hot out, the high dry heat of August, but he was in the shade and his flanks were still going in and out like bellows. Roger tracked down Dr. Callan in Colorado. He told Roger to take Charlie’s temperature and, if it was over 103, to give him the powdered oral antibiotic he’d prescribed for him at CSU, the one Roger hadn’t been able to give him since Charlie stopped eating. Roger called his neighbor, the vet Tom Parker, who recommended giving him an injection of antibiotics right away and started him on a seven-day course. Parker came over and the two of them tried to get Charlie under control. In his distress, though, Charlie was totally uncooperative. Parker and Roger finally tied him down in the corner of his stall with three ropes. Charlie only stopped struggling when Roger finally laid his hand on him. Even in his frenzy, he knew Roger’s touch. Charlie’s temperature was 102.8.

Only now did Roger glance at the label of the oral antibiotics Callan had given him; the drug was indicated for the treatment of a condition Roger had never heard of: shipping fever. What the heck was that? At CSU nobody had mentioned shipping fever. When he showed the label to Veryl, she went and Googled it.

Shipping fever got its name because it often occurs in animals that have been transported long distances. Its real name was bovine respiratory disease, its medical one pleuropneumonia, and it was often deadly. The stress of travel can decrease immune function in the lungs, but there were several purely physical factors as well. Trailers are full of respiratory irritants, including hay dust, mold spores, exhaust fumes, and the ammonia from the urine. When a horse, cow, or sheep keeps its head above chest level for several hours at a time, bacteria are given a chance to thrive in the animal’s lower airways, making it hard to clear mucus and bacteria from its lungs. It’s not uncommon for an animal that hasn’t lowered its head for twenty-four hours to develop pneumonia. Because shipping fever costs cattle producers $600 million a year in lost livestock, veterinary medicine was desperately trying to understand the disease and develop recombinant DNA–derived vaccines to prevent it.

The early signs of shipping fever, which include mild depression, lack of interest in food, and increased respiratory rate, can become apparent during travel, but may not manifest themselves for up to two weeks. Even then, the symptoms could be very subtle.

BY WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 6, Roger thought it was premature to call Charlie recovered, but there was clear improvement. The antibiotic was doing its job. He grazed a bit on the rope lead and felt strong enough to trot along the arroyo on the property, dragging Roger after him. The next morning, he ate a very small amount of hay and straw and took a bite of carrot. By Thursday evening, Roger could see continued progress. “He’s feeling good,” Tom Parker said. “We’ll get him through this.” Veryl high-fived Roger, who hesitated for a moment to slap her hand. He was not naturally optimistic, and he didn’t feel that they were in the clear yet.

On Friday, he could tell they weren’t. Charlie’s head was down. He put up with the shot, but he wouldn’t touch food. A zoological-nutritionist friend had recommended an appetite stimulant, which Roger tried to squirt through a syringe into Charlie’s mouth. He did this by lying on his back underneath him, hardly the safest place in the world to be, since in his distress Charlie would no longer let even Roger touch his head or horns.

“Open up. Just have a little.”

Charlie wasn’t even strong enough to grunt.

“C’mon,” Roger said, poking at Charlie’s closed mouth with the plastic syringe. “C’mon, now, Charlie. When you were little you wouldn’t stop eating. You remember how you used to tap dance for more the moment you finished a bottle? And then when you weren’t sucking a bottle any more—please open up, Charlie—you ate constantly. Wiped out every flower bed. Good thing I introduced you to carrots—some days it was the only way I could get you to do anything. Open your mouth and let me squirt some of this crap in there! Charlie! I’m a fifty-nine-year-old man lying on his back underneath a buffalo! I’m begging you! Open your damn mouth and eat!”

Sweat poured down the sides of Roger’s face. “Charlie,” he said, “you’ve got to eat something or you’re going to die.”