twenty-two

Tom Parker explained to Roger that the bacteria sometimes formed a resistant ball inside the animal. Roger imagined a shaking fist of bacteria inside Charlie. He and Veryl were in crisis mode now. Roger remembered that on the phone Rob Callan had mentioned two other antibiotics that might work. Since the original one seemed to be losing its effectiveness, on Friday afternoon Roger drove an hour into Albuquerque to pick the others up at a veterinary supply store.

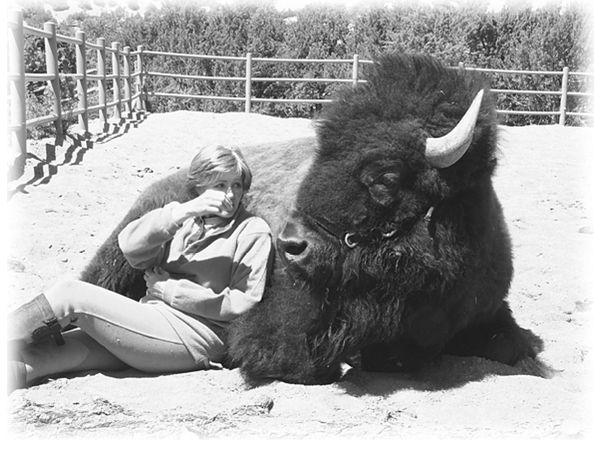

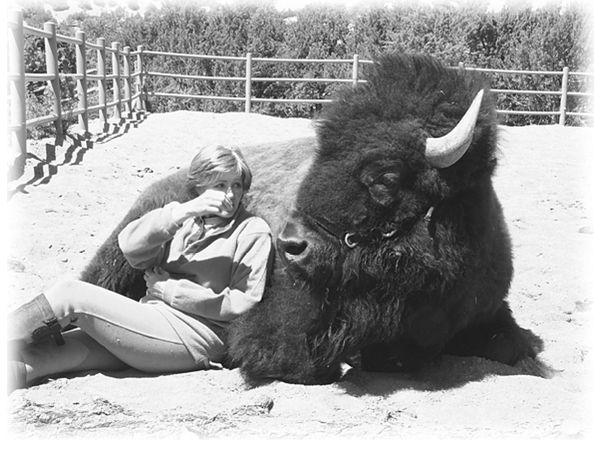

Charlie didn’t respond to either, so on Saturday it was Veryl’s turn to make the trip. Desperate, she asked everyone in the store if they had any fresh ideas. When a lady vet there suggested she try running a tube down his esophagus and feeding him some concoction she described, Veryl bought the necessary supplies. She wanted to tell the woman how much Charlie meant to her, but how do you explain to a stranger that you have a buffalo at home who’s like a child to you? When she got back to the house, she put cattle feed, probiotics, electrolytes, acidopholus, vitamin B-12, and a few other ingredients into a blender. With help from a vet from Eldorado who specialized in this sort of thing—it now felt as if they’d gotten every vet in the area involved—she and Roger secured Charlie again with three ropes and got the tube down his esophagus and fed him. He was too weak to protest.

It was Veryl’s turn to be pessimistic. Roger clung to hope, but still he took Veryl aside.

“Honey,” he said, “we’ve got to think about where we’re going to put him.”

He paused, alarmed by what he had just said. But it was as if the words were also an insurance policy; once they were out of his mouth, he felt protected by them. The words dragged him forward into the future, but defended him against it.

“It can’t be very far from the barn,” he added. “He’s too big.”

“Next to Gwalowa,” Veryl said. Gwalowa, the exceptional Arabian she had been riding when she met Roger seventeen years before, was buried just outside the arena that had been Charlie’s home. “I think he would want to have another exceptional animal for company.”

“It’s always been one of his favorite grazing spots,” Roger said.

“Superb animals sticking together,” she said.

Roger called a young man who had done some work for them in the past and told him that he and his backhoe might be needed in the next day or so. It felt like another painful betrayal of Charlie—like leaving him at the Montosa Buffalo Ranch two and a half years before—but Roger was by nature and training a man who prepared for all the possibilities.

Roger and Veryl planned to go see the movie Seabiscuit that evening. They needed the distraction. Around dinner time, they walked Charlie around a bit outside his stall, thinking it might help clear his lungs. He walked one lap, refused to do a second, and went back to his stall, where he lay down, tongue out, breathing with difficulty. They left him there, but one or the other returned to check on him every twenty minutes. After one of her trips, Veryl told Roger that she was afraid Charlie was dying and maybe they shouldn’t go to the movies.

At just that moment, the new vet from Eldorado happened to call to ask after his new patient. Roger and the vet spoke for a while and concluded that Charlie was okay. But it hardly seemed so to Veryl when she went out to the barn. She walked gingerly toward Charlie’s stall, as though she were the lame one. Her heart was in her throat. She walked past her horses Toddy and Matt Dillon and looked into Charlie’s stall. Charlie was in the process of shifting from lying on one side to the other. He had gotten halfway up on buckled legs—like the arms of a weightlifter unable to press a barbell—and was barely able to lower himself. “Good boy,” she whispered, choked up at the thought that so much life might be sputtering to an end. But when Charlie was through settling himself, she allowed herself to find in his small achievement some cause for genuine hope.

Drained, she and Roger dragged themselves to Seabiscuit. From the beginning, Roger didn’t want to be there, and it was all he could do to stay in his seat. Of all the movies to be seeing, why did it have to be this one, with all the parallels? The animal with the bad leg that no one had wanted, no one had understood, until a man had seen in him a big soul and special drive and, with patience, kindness, and understanding had released the champion within. It wasn’t whether you finished first, or how many people were watching when you crossed the finish line, but where you had started, and how far you had come. During Seabiscuit’s climactic triumph over War Admiral, Roger felt an almost unbearable sadness.

The minute they got home, a little before ten, Roger put on his boots and headed for the barn, asking Veryl to go inside the house to make some mush in the blender for Charlie. Veryl headed toward the kitchen, grim visions of intubating Charlie again in her head. But why was she letting Roger go alone? Why had Roger sent her into the house?

She stopped, hesitated, then turned back toward the barn. Before she even entered, she could hear Charlie’s rapid breathing.

“He can’t get air,” Roger said, crouching near Charlie, who was in the sternal position. Flag, the Rottweiler, the one dog in the house with strong maternal instincts, pushed open the stall door with his nose and padded in to see what she could do.

Roger braced Charlie on either side with hay bales. Charlie’s eyes were puffy. Gone was the vulnerable look he had worn on and off since his visit to Colorado State University more than three weeks ago. In its place was a look of great ending. The life was slowly going out in his eyes now, like house lights dimming in a theater.

“He’s dying,” Veryl whispered to Roger. The words came out on their own, although she knew she wouldn’t have said it in front of Charlie if she thought he was really there. But he wasn’t; she could see that he had already left the living.

Roger felt his throat tightening and a hot pressure building behind his eyes. It was unimaginable, after everything, that Charlie would leave him now. He was supposed to outlive all of them, to go on and on, to have been a gift for Roger and Veryl to leave behind to others. How could any creature with so large a heart and so fierce a desire to live just slip away? Roger thought they had had a deal, and this was not part of it. For a moment, Roger was as numb as a child, all raw wordless hurt and no understanding.

The buffalo, lying sternal with his forelegs folded neatly under his chest, shuddered once. As the air in his lungs escaped for the last time, it came out as a bellow that made him, for an instant, seem entirely alive again. Then his head fell forward and he died.

It took Roger a moment to catch up to the reality of it. It felt like he was running after him again, down the arroyo, except that when he caught up, Charlie was no longer there.

Roger reached over and gently closed Charlie’s eyes one at a time and it was as if Charlie were sleeping, except for the fact that his nose touched the ground.

THE NEXT DAY, the young man with the backhoe came and went about his business quickly and quietly. Because of the heat, Charlie needed to be put to rest without delay. Roger didn’t want Veryl to see any of it, the digging of the grave or the indignity of Charlie being picked up in the backhoe’s bucket and carried across the arena, through the gate, and over to his final place. He buried Charlie next to Gwalowa, and tossed a few carrots in with Charlie before the backhoe finished its work, and then he arranged some rocks in the letter C to mark the spot. That evening, Veryl went out to the arena alone and raked over the backhoe tracks. Roger got into his truck and went out in search of a soccer game.