No. 17

Understand your electrical system

And restore the power when it goes out

Your home’s electrical system is a minor miracle. It takes one of the most dangerous forces in the universe and distributes it safely throughout your home, making every minute of your day more convenient. Here’s how it works.

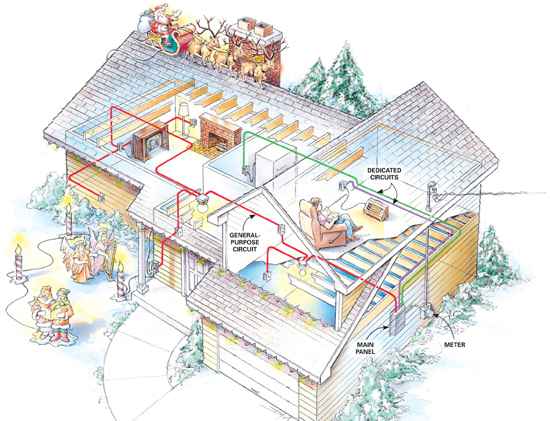

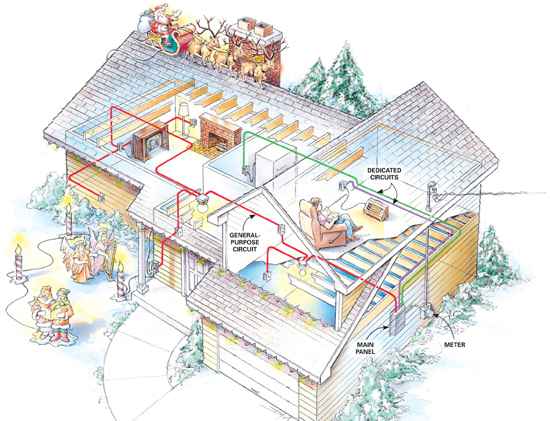

How power gets where you need it

Electricity runs through underground or overhead power lines to an electrical meter, which measures your power use and tells the power company how much to charge you. From there, it goes to your main panel, which provides an enclosed space where the big incoming wires are connected to dozens of smaller wires that snake throughout your house. Some of these wires form general-purpose circuits that branch off to several lights and outlets. Other wires create dedicated circuits, each of which serves a single high-demand purpose, such as a fridge, electric heater or the outlets near your kitchen countertop.

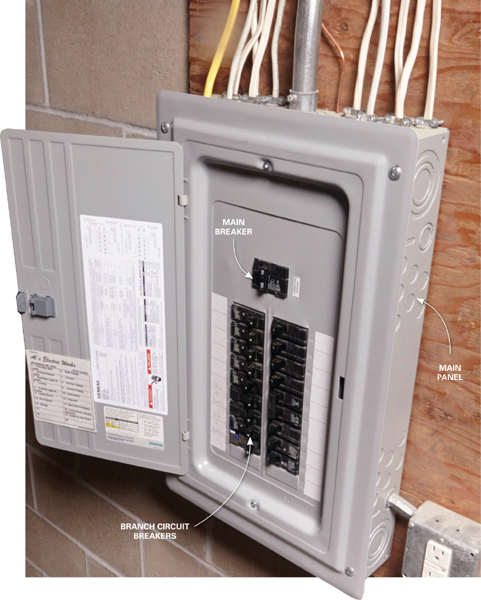

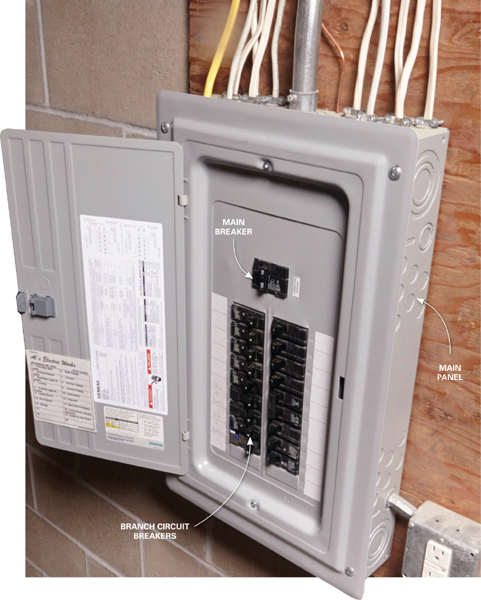

The main panel

It’s usually a gray metal box located in the utility room, garage or basement. There’s no need to worry about opening the panel’s door; all the dangerous stuff is safely contained behind a steel cover. Behind the door you’ll see a main breaker, which can shut off power to your entire house, and rows of breakers, each controlling an individual branch circuit.

What’s a breaker?

Breakers are the most important safety feature of your home’s electrical system. Basically, a breaker is a safety switch. When more power flows through a circuit than the circuit was designed to handle, the breaker instantly shuts off. And that prevents fires. Aside from that, breakers allow you to turn off the power so you can safely work with wiring.

Find a tripped breaker

When a breaker “blows” or “trips,” the switch lever snaps away from the “on” position. But it doesn’t go all the way to “off,” so you may have to look closely to find the switch that’s not in line with the others. Some breakers have a little window that turns red or orange to indicate a trip.

Reset the breaker

You can’t push the switch directly from the tripped position to “on.” First push the switch all the way to “off,” then back to “on.” Don’t worry if your hard-wired smoke alarms beep as power is restored; that’s normal.

Blown fuses

If you have an older home with fuses rather than breakers, you’ll have to peer into the window of each fuse. The difference between a good fuse and a blown fuse can be hard to see, so you’ll have to look for the fuse that doesn’t look like the others. You’ll see that a spring has collapsed or a metal strip has burned, leaving a gap in the strip. Unscrew the blown fuse and screw in a new one, just like a lightbulb. Make sure to install a fuse with the same “amp” rating. Never, ever install a fuse with a higher amp rating.

Voice of experience

Don’t trust labels

Inside your main panel, you’ll find labels or lists indicating which breaker controls which circuit: “master bedroom lights and outlets,” for example. These labels are a good guide, but they’re not completely reliable, especially in older homes that have been through repeated remodeling. For example, you might find that all of the outlets in a room—except one—are on the circuit listed on the main panel. That orphan outlet may be connected to just about any other circuit and not listed on the panel. As every electrician has learned the hard way, you can’t trust those labels.

Al Hildenbrand, master electrician and The Family Handyman Field Editor

If a breaker trips again and again…

A breaker or fuse that won’t “hold” means one of two things: You have a serious problem such as a short-circuited wire, or you’ve overloaded the circuit by plugging in too many electric devices. First, try to take some load off the circuit by plugging into other outlets that are on other circuits. Appliances that draw lots of power are usually the overload culprits (space heaters, window air conditioners, hair dryers, irons, etc.). If you can’t prevent breaker trips this way, there’s a good chance that you have a more serious problem. Call in an electrician.

What are GFCIs and AFCIs?

Ground-fault circuit interrupters and arc-fault circuit interrupters detect potentially dangerous flows of electricity and turn off instantly, before they can do any harm. Both can be built into breakers or outlets (a test button on a breaker or outlet indicates that it’s GFCI- or AFCI-protected). Electrical codes require GFCIs in areas that might be damp, like kitchens, bathrooms, outdoors or in the garage. AFCIs are required in all living areas, except bathrooms. That doesn’t mean you have to call in an electrician to install them immediately. But a remodeling project could trigger these requirements, adding safety to your home—and major expenses to the project.