IT IS THE MIDDLE of June. Warm-weather clouds are sailing across the Weald towards Canterbury. I watch them, drinking coffee by the barn, my legs swinging beneath me on the edge of the tall brick step on its northern side. A wonderful day is laid out in front of me and I feel as happy as a dog: a pale blue sky, a rippled earth. It feels like an arrival. The warmth is finding its way between my shirt and skin. I watch the cloud-shadows slide over the wheat, following them as they hurry across the Eight Acres, the corner of Frogmead, on to the long flat of Large and then Lodge Field, across the lane and into Robert Lewis’s seamless arable ground stretching to the north. The shadows slip across the grain of the country in the way that fish cast shadows on the bed of a stream: each patch eases over the bumps and hollows as if gravity did not exist.

The larks are up above Frogmead and the Lower Moat and they are brightening the morning like sequins, glimmering spots of song heard against the sky. Last night with some friends, I went out into the fields and we listened to a single nightingale in the scurfy wood, beginning its song again and again, each time a new variant on what had come before, as if nothing inherited or borrowed was worth considering. Every snatch of its song was unfinished, an experiment in gurgle-beauty. You wanted him to go on but he didn’t, always stopping when the song was half-made. We listened, standing in the warm wind, waiting for the next raid on inventiveness. Every part of that bird’s mind was restless, on and on, never settling on a known formula, an unending, self-renewing addiction to the new, to another way of doing it, and then another, all in the service of a listening mate and the survival of genes. That is the nightingale’s irony: his brilliantly variable song is indistinguishable from his father’s or his son’s. Invention is nothing but the badge of his race. It is as if new and old in him were indistinguishable. That is the nightingale lesson: inventing the new is his form of repeating the past.

Is that the model here? Is that how we should do it too? I have been making some radio programmes about Homer and his landscapes. Reading the Odyssey now, at the end of this Sissinghurst story, brings something home to me. People think of it as the great poem of adventure and mystery, of a man travelling to strange worlds beyond the horizon, of the threat and challenge of the sea. That is true but it is only half of it. The second part, as long as the other, is devoted to something else: Odysseus’s home-coming to Ithaca and his ferocious desire, in the middle of his life, after twenty years away, to reform the place he finds, to steer it back on to a path it abandoned many years before. Homer certainly knew about homecoming. Odysseus thinks that all he need do is re-create the order he remembers from his youth, to cleanse the place of everything wrong that has grown up in the meantime and re-establish a kind of purity and simplicity over which he can preside. I hear the echoes of what I have done. ‘Nowhere is sweeter’, Homer says, as Odysseus bends to kiss the green turf of Ithaca, ‘than a man’s own country.’ That is what we might like to think, but the truth is harder. Nowhere is the desire for sweetness stronger than in a man’s own country and nowhere is it more difficult to achieve.

Odysseus soon realizes that home is not safe or steady. If he is to re-establish the order he remembers, he has to use all sorts of cunning and persuasion, and in the end even that is not enough. His longed-for sweetness clashes with the realities of imposing it on a place that has changed. The resolution the poem comes to is terrifying: Odysseus slaughters every one of the young men who have been living in his house and corrupting it. He leaves the palace littered with their bodies and his own skin slobbered with their guts – his thighs, Homer says at the end of the killing, are ‘shining’ with their blood – and then, with the help of his son, strings up the girls those men have been sleeping with, their legs kicking out, the poem says, like little birds which have been looking for a roost but have found themselves caught in a hidden snare. Odysseus thinks of it as a cleansing, a return to goodness but the poem knows that the desire for sweetness has ended only in horror and mayhem. He thinks that order can be imposed by will; the poem knows that the vision of perfection brings war into a house and leaves it broken and bloodied.

It is a sobering drama, an anti-Arcadia, with a deep lesson: singular visions do not work; only by consensus and accommodation can the good world be made; returning wanderers do not have all the answers; and anything which is to be done in your own Ithaca can only be done by understanding other people’s needs and their unfamiliar desires. Accommodation, not simplicity, is all. It was a lesson I had taken many months to hear.

So the nightingale has it. Newness is not a new quality. Ingenuity and inventiveness are central parts of life, human and non-human. Stay loose, it says; don’t rigidify; accept that you have inherited from the past many beautiful and varied ways of being. And once you know that, sing your song, which attends to the present, and is even to a hymn to the present, to the long sense of possibility which has the past buried inside it. Elegy, which is a longing for an abandoned past, is not enough. Elegy, in fact, may do terrible Odyssean damage. It feeds off regret, and even though regret is beautiful and moving, it gives nothing to the future. Regret is a curmudgeon with a way of stringing up the innocent girls. This story, then, is a lyric, a song to what might be, not a longing for what has been. There is no reason when I look at what we have done here and what we are all doing here now, that we cannot say, in future, ‘This is what we did then, wasn’t it wonderful?’

It has been quite a year. After the decision to go ahead had been made in December 2007, things started to happen. Advertisements were put in relevant papers for a project manager; for a vegetable grower and a deputy; and for a farmer. Early in 2008 we had a string of open days on which candidates came to Sissinghurst for their interviews and to be walked round in the cold and the wind. We took them up the tower, told the story and showed them the land and buildings. There were some oddities – people whose main experience had been in growing mangoes; a man who wanted to cover the whole farm in geodesic domes for his tomatoes; a woman who didn’t want to walk out in the fields because it would get mud on her high heels; a father and son who talked about the ways in which they would drive the place for maximum profit: ‘Are all these hedges really necessary?’ – but it was exciting. Here at last, living in flesh and blood, were the people who were going to make the change.

The first to join was the new project manager. Tom Lupton is a huge, big-voiced man, Oxford-educated, with a hunger for order and eyebrows that jump at each emphasis in a sentence. ‘We REALLY do need to get this into a BANKABLE document.’ He is now in his 50s, lives nearby in Biddenden and has behind him a long career in the developing world, setting up vast agricultural and forestry projects, or as he puts it ‘getting half-nebulous desires into practical, sequenced action.’ None of us could believe that such a qualified man should have applied for this job. It was like having the engineer on the Aswan dam supervise the building of your pond. Why was he doing it? Certainly not for the National Trust salary. More because it was ‘an ideal thing to get involved with. It was an idea with a very holistic view, doing things I have spent all my life doing, using land to improve people’s lives at the same time as protecting the environment, and done by an organization which takes a long term view. It was a marriage of all those things.’ When Tom arrived, and his voice started to boom around Sissinghurst’s fields and buildings, it felt as if the admiral had joined the fleet. ‘You need to be aware,’ he said, ‘that there are many, many risks associated with this and one of my qualifications is that I will be able to extract you with minimum damage if it all goes wrong.’

Next was the vegetable grower. The ad in Horticulture Week came out in February. Amy Covey, a twenty-three-year old, with a big-teeth smile and a blonde, tanned presence as buoyant and English as her name, was working in a private garden in the Midlands. ‘I remember looking at it at tea break. We always looked at Hort Week and this ad ticked every single box I ever wanted to do. Growing, supplying, being in charge.’ She laughs. ‘I have known what I wanted to do with my life since I was fourteen.’ After training in Sussex and then with the RHS in vegetables and fruit, she was looking for ‘the next layer. I didn’t expect to do what I am doing now for another three or four years. When I saw the job advertised my heart leapt, it was everything I ever wanted. It was coming home.’ She was young to take it on, but we all felt when she came for an interview and we showed her the bleak unploughed, wind-exposed stretch of ground that was going to be her vegetable garden that her sense of enthusiasm and capability, her wonderful undauntedness, was just what Sissinghurst needed. Energetic, open-minded, wanting to learn, neither arrogant nor set in her ways: if any single factor is going to make Sissinghurst’s vegetable garden work, it is Amy Covey.

Third in this flow of new blood were the new farmers. The advertisement in Farmers Weekly made it clear that the job was for two people, to run both the farm and the bed and breakfast in the farmhouse. There were forty different applications, six were shortlisted and out of the pile came Tim Prior and Sue Watson. He had been a London policeman, with all the policeman’s understanding of quiet authority, and then a lecturer in an agricultural college. She had experience of organic sheep and cattle in Devon and running an upscale B&B. Both were clearly business-canny people and understood that the proposition here was more than just a straightforward farm job. They would thrive by tying together what they grew with an enveloping, everything-connected environment for people to enjoy as a whole. That was the point. Bed & Breakfast, farm, restaurant, café, meat sales, wool sales, sheepskin sales, enjoying the garden and the woods: it was all one thing.

When they’d seen the advertisement, Sue had done some research on the internet, ordered an exceptionally obscure pamphlet on the history of the parish in the 19th century and had come up with the fact that Sissinghurst Castle Farm had generated a surplus of £3,600 in the 1850s. ‘We knew then that is what we wanted to do,’ Sue says. ‘I was the one that saw the ad and I thought “Ooh that’s us.” The whole profile of what you were wanting to achieve here. I thought, “I’ve done that, he’s done that, I could do that, he could do that. That sounds really good.” I felt that the farm project could be such a wonderful part of the history of the place. And it would be so wonderful to be part of a history that will still be going on in a hundred years’ time.’

What appealed to them was exactly the coming together of history, business, the land, people, animals, farming, the place and its natural life which Sally, Sarah, Jonathan and I had been pushing for so long. They had some capital to back them up, as well as a small herd of British Shorthorn pedigree beef cattle, which they would bring with them, a flock of Romney sheep and another of Shetland sheep whose caramel-coloured wool would go into jerseys, designed by Sue and made up by a team of knitters. Commerce was at the heart of their idea, as it needed to be, a version of retail farming which would feed off the Sissinghurst name, while putting its own qualities of top-level stockmanship and land management back into that name. They understood from the start that a virtuous circle was waiting for them here.

Tim:

It is a jump into uncertainty but then life is uncertain. I could be made redundant from the college in a year’s time. If you don’t take risks you are never going to get anywhere are you?

Sue:

There is an element of arrogance about us, thinking “We could do that, we could make it fantastic.” We may be wrong and we’ll fall flat on our faces but we thought we could give something to it as much as it could give something to us.

Tim:

We are middle-aged but we are very ambitious about things. Even if we hadn’t seen the ad for Sissinghurst we would still have been out there looking for something. Rather than just sit on our laurels and think we’ve got fifteen years before we have to call it a day.

I remember you saying when you came here on the interview day that the farm didn’t have to be driven for all it is worth because the thing that was going to keep your family going was the B&B. And the farm is almost an entrance ticket to the B&B.

Tim:

The B&B is going to be the banker, the monthly cheque coming in. As far as the farm goes, it is going to take time to get it running, getting the right system. We have got to learn the land here, what we can do and what we can’t. We were told “Ooh that field is dreadfully wet down there,” and we walked down there and said, “Where’s this wet field?” The one down by Whitegate.

Adam:

Oh yes, that is really wet down there.

Tim:

Not in Devon it’s not! If it was really wet, you’d be up to here in mud. So where’s this wet field?

Sue:

We have never seen anything quite like this advertised before.

Tim:

We want this to be a complete circle so that it almost runs itself, everything that is born here goes off it on its legs, or in the stomach of a customer. The sheep will follow the cows round and the arable follows the sheep, so that you get a complete system. Twenty tons a year of the cow’s manure from their winter housing is going on the veg garden and then whatever is produced here is sold locally or to south London or whatever and we build up the brand name of Sissinghurst Castle Farm.

We’ll be selling the pedigree stock live. I would like to sell it all live if I could but I know we can’t. We are also changing the herd name to become the Sissinghurst herd.

Tim:

That’s what their names will be: Sissinghurst Brian, Sissinghurst Boris, Sissinghurst Gordon. You could name a cow if you like, Adam.

Adam:

Sissinghurst Vita?

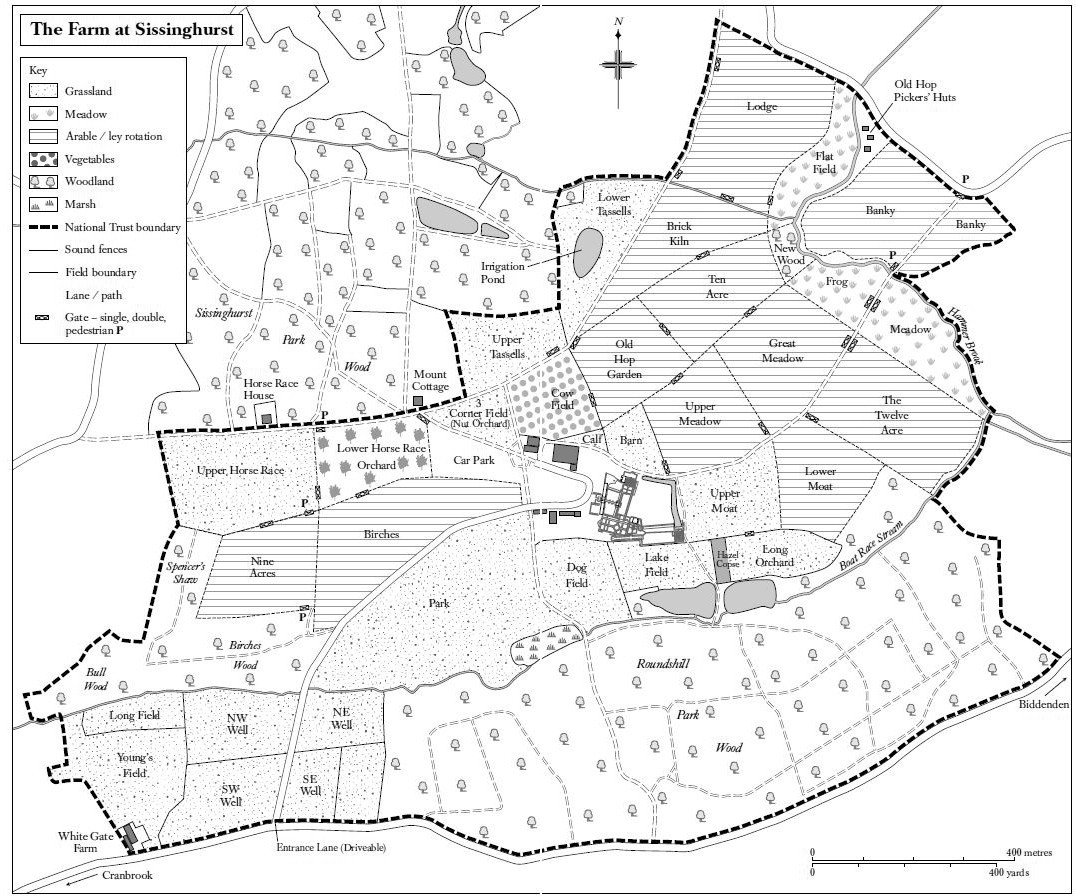

Tim and Sue wouldn’t arrive with their animals until September, but the appointment of these new people to the Sissinghurst world felt like the dawning of a new day to me. Tom was there from early March, Amy soon afterwards. Ben Raskin and Phil Stocker from the Soil Association came up with a design for the vegetable plot: three and a half acres, 9 different segments, the crops rotating through it year by year. Peter Dear had it manured, drained, ploughed, fenced, gated and hedged. An extra segment was added for the children of Frittenden school to grow their own veg. The site for the polytunnels was set up behind a screening layer of oak trees. Irrigation was put in. Plans were made for the drained off water to be collected in a pond in Lower Tassells and then pumped back up to the top of the site where it could re-used to irrigate the crops. Peter and a party of volunteers made windbreak panels from the wood, using chestnut poles and sliver-thick chestnut slices which he wove between the uprights. Birch tops and hazels were cut for the peas and beans to climb. Peter drew up a plan for the whole farm in which all the hedges, gates and stiles were carefully and exactly detailed.

I loved it all. Suddenly, this new life was springing up out of the inert Sissinghurst ground. It was slightly rough at the edges. Despite some ferreting earlier in the year, the rabbits wrought mayhem with the early plantings and the beds had to be surrounded by low green electric fencing. Black plastic mulch marked out each strip of veg. The soil was not as good as we all had hoped and the gardeners had pushed grapefruit-sized lumps of clay to one side so that they could get each bed half-level. The sown lines were a little wobbly and there was an ad hoc feeling to the garden, but it was this hand-made quality of the vegetable garden which touched me. Not for decades has someone attended to this ground in this way. The paths worn between the rows by the boots of the gardeners and their volunteers; the picnic tables for the Frittenden children; and the Handbook of Organic Gardening left on the tea-shed table: all were marks of a new relationship to this place. They were the signs of Sissinghurst joining the modern world, the same movement which had re-invigorated allotments across the country, which understood the deep pleasures and rewards of growing your own, which loved the local in the most real way it could. Did it matter that flea beetle was massacring the brassicas, the Rocket was bolting, the gooseberries dying, wire-worm making hay with the carrots or the rabbits were eating everything the Frittenden kids had sown? Not really. Because all of that could be sorted out with time and this new presence of people out on the ground – bodies in the fields – was exactly what I had dreamed of four years before: land not as background, as wallpaper or flattened ‘tranqillity zone’, but the thing itself, engaged with by real people, the pants sown in it bursting into a third dimension, the soil the living source of everything that mattered.

A second grower, David Reynolds, was recruited to work alongside Amy. Sarah drew up a planting list of what the veg garden could and should grow, a cornucopia menu that stretched across the months and years. Intensely productive but not labour-intensive salads, herbs, leafy greens, chard, spinach, courgettes and beans. Alongside them all the tomatoes, pumpkins and squash, carrots and sugar snaps (peas themselves were thought to be too labour intensive for the kitchen – too much shelling for not enough product.) Third were ‘the unbuyables’ – unusual herbs such as lovage, the edible flowers, red Brussels sprouts, stripy pink-and-white beetroot, as well as yellow and purple French beans. All of them, as Sarah said, ‘for flavour, style and panache.’ Kales, leeks and purple sprouting broccoli, ‘the hungry gap crops’, would grow through the winter and be harvested in March and April when the restaurant opens. Raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries and red and black currants were planted in long lines between the nine sections of the garden, both to provide windbreaks and to give the plot a visual structure. Fifty new volunteers were recruited to help work there and in the polytunnels.

Tom, Peter and Amy drew up plans for the orchard. A third of it was to be filled with 90 big old-fashioned apple trees (mainly juicing varieties so that the apples could be collected from the ground and no one would have to climb high in the trees to pick them). The rest, just over three acres, was to be smaller modern trees, 1500 of them, no more than eight feet tall, for easy picking and tons of fruit. Plums, apples, pears and a few cherries: a vision of blossom and fruiting heaven. I had the idea of putting thirty acres of hay meadow back into Frogmead along the banks of the Hammer Brook and meadow experts came to advise. Peter was designing wet patches for birds and dragonflies along the streams and a new rough wood to extend the habitat for nightingales. We bought some new disease-resistant elms to place around the landscape as the great towering tree-presences of the future. Architects and landscape designers looked at Whitegate Farm to see how that could be made more efficient and less ugly: a complete rebuild. Other architects redesigned the farmhouse as a modern B&B, in which Tim and Sue could live on the top floor. Meanwhile, the Priest’s House was done up for the new farmers to live in until the farmhouse was ready.

Everywhere you looked, all through the spring and early summer at Sissinghurst, change was underway. More people, new people, new structures, new land uses, new relationships. All these changes were exciting but it also felt like a long, slow earthquake heaving up under this most stable and intricately defined place. Inevitably, the stress and grief began to tell. Difficulties, tensions and rows started to break out. There were tears and snubbings, huffs and confrontations. No one had quite understood how deeply these ideas for the place, and all its emphasis on re-invigoration and the re-animation of the landscape, would seem disturbing to the people who lived and worked here.

One afternoon I sat down and talked to Sam Butler, the National Trust’s Visitor Services Manager at Sissinghurst, a funny and warm-hearted woman, who has been here since 1994. She had started as a part-time secretary, one of three office staff. ‘We are still in the same office now. There are fourteen of us with seven computers which we all have to share. And there are five telephones which have got to be answered. It does take up quite a lot of the day.’

The stress levels went through the roof. People were getting angry, offended, offensive and dismissive. Thirty-five permanent staff, fifty to sixty seasonal staff, one hundred and twenty to one hundred and thirty volunteers, plus another fifty volunteers coming on for the vegetable garden, not enough office space, not enough computers, not enough desks or chairs, and the great cuckoo of the farm project and all its building implications landing itself in the midst of this. Everything I wanted for Sissinghurst – rerooting it, reconnecting the parts, generating some overall wellbeing – all of that was the opposite of what happened.

Change is hard in any business but when many of the people live on the site, when they have worked there for years and feel that lives, their ideals, their work and their homes are entirely bound up in a vision of a place as it is – as they have made it – then change, however good or bad it may inherently be, is even more difficult to accept.

I talked to Tom Lupton about what was going wrong. He is almost the definition of a wise dog and one of the problems, he said, was that I had not properly understood how deeply attached other people were to Sissinghurst. I had assumed I was the only person to whom it meant a great deal.

‘There is a lot of emotion tied up in this project. From you, of course. You have obviously staked a lot of emotion in it. But that’s true of a lot of people who live and work here. Sissinghurst is not like going into Tesco’s. People come here and very quickly form emotional bonds. They love it. It feeds many individual needs, which are very difficult to get fed in many places these days. Sissinghurst spoon-feeds it to people. As you walk from the car park, you are given these wonderful, sensuous experiences. In through the gateway, the tower, you wander into the garden. It’s beautiful but it’s obviously been beautiful for a long time. That is very reassuring and very comforting. It’s a refuge but it does a bit more than that. I can’t believe that many people don’t leave here feeling better. It’s a recharging point and for people who work here it has an increasing value to them the more they are steeped in it. You, Adam, need to be aware how many other people have loved being here.’

It was well said and I heard it clearly. I asked Sam about this too. Why were people so attached to Sissinghurst? Was it just a tranquillity balm? I had always thought of it as a place that should have life and vitality, which should feel enriched by all the things going on here, by a sense of a living landscape not an embalmed one. Sam gave me a skeptical look.

I know you would like to bring the farm up close around the garden so that there was more of a contrast. I can see that, but I quite like the feminine, soft, National Trust sanitisation. I quite like that because that is where I am comfortable but what you are proposing is much more masculine and that’s unknown territory. I am not sure how I am going to respond to that.

Really? Was a sanitized, blanded out soft zone really what was needed?

I like it and most of our visitors like it. It makes it accessible and for those who don’t know the countryside, they need their hands holding, giving them a comfort zone so that they can access it without it being too threatening.

How was she feeling about the whole transformation? A week or two before, at a meeting, she had suddenly coloured up at something I said.

It was like a slap in the face. I had been listening to you and Tom and I suddenly realized that this place was going to change for ever in the way I felt about it. When I drove up the lane, the place that I had known for such a long time, that drive up the lane would be bringing me to a different place and I wasn’t sure. It didn’t matter whether it was good or bad. I just didn’t know how I was going to respond. I knew it was different and that for me was a loss, because I have been tied to this place for such a long time.

We have visitors who come here every Saturday morning to read their papers in the orchard, who have come here maybe with a partner or a husband or a wife or a child they have lost and they come here to reflect as well as to enjoy the flowers and the views and the vistas. And you know we must look after those people too.

All this was an education for me, almost the first time I had ever listened to the stories other people at Sissinghurst were telling me. Alexis Datta, the head gardener, continued to be worried, but she too has seen out many years and crises at Sissinghurst and thinks it will only be a source of short-term grief. ‘I am hoping in a while it is all going to feel like part of the place. I think it probably will. At the moment it just feels as if everything is “Oh my God, what is going on?” A sympathetic farm will be an improvement,’ she said.

I’m hoping it is not going to be a mock historic farm. Having livestock will enhance it a lot. You don’t see a tractor now. It is nice to see people working on the land as long as they are not dressed up in smocks. It is slightly sentimental if we are going to have nut trees and orchards which everyone else is ripping out. But now we have got Amy attempting to grow things on the land and we will soon have a farmer and they are doing it for real and it will be real. I think it is going to be ok.

Those sentences were undiluted music to me. ‘I think it is going to be ok’: I had been saying that for months. Now people were saying it to me.

The real pinchpoint, though, was the restaurant. It was vital that the restaurant changed to reflect what was happening in the wider landscape. It would make little sense to set up all these connections between land, place and people if the restaurant continued to produce food that was much as it was before. Sarah, who has a decade’s experience of growing and cooking vegetables for her gardening school in Sussex, took on the task of introducing the restaurant to these new hyper-local sources of produce, urging on them a new responsiveness to what would be coming in off the field. For months, over these questions, there was an agonized non-meeting of minds.

Both sides felt deeply unappreciated by the other. Ginny Coombes, the restaurant manager, who has been generating quantities of cash for Sissinghurst year after year, while also responding to the Trust’s own local and seasonal agenda, felt bruised by the whole process.

There is no appreciation of how far we have come, or of what we have taken on. A lot of ideas have been thrown at us and it isn’t easy. We are moving in the right direction and we are doing a lot already with local and seasonal. That’s my mantra! It is something the Trust has been working towards for years. And we are improving year on year. Someone needs to say, “Listen to the staff, they run it, they know what they are doing. We want to help you improve what you have got already.” But we don’t feel that anyone is saying that.

It was never going to be easy. For chefs and restaurant managers used to high-pressure, high-volume production of meals for hundreds of visitors, often in less than perfect circumstances, all our talk of ‘the dignity of vegetables’ was not even funny. Mutual frustrations erupted. Sarah pursued her gospel: vegetables are cheaper to grow than meat, better for the environment, better for you, utterly delicious when they are so fresh, and make you feel good when you know exactly where they have come from. And Ginny said ‘Look, do you know what it is like in here on a busy day?’

When you came to me three years ago and said “What about growing our own veg here?”, I thought that would be a wonderful thing. But it is all got so over-complicated. I love what Sarah does at Perch Hill and I listened when Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall came here and said we should have a Tart of the Day. That is all fine when you have fifty people to feed. When you have got a thousand people a day, they want choice. That is the plain and simple fact. And, now, people are looking at their purses more and more. If they have to choose between something usual, what they know, and something more expensive and localized, they are going to choose the cheaper option more and more.

Early in June 2008, to get some understanding of what Ginny and her staff were having to deal with, Sarah and I worked in the restaurant for two days, her in the kitchen, me on the tables, behind the counter and doing the washing up.

Seeing it all from the other side was pure reality-check. The customer demand was relentless and the need to shave costs unbending. The building – a restaurant inserted into an old granarycum-cow shed – is badly laid out. For the staff it is often unbearably hot as wafts of hot air come from the industrial dishwasher, the heated counters or the ovens. The clearing away system does not help the waiters and there is a lot of double handling. The queue for a pot of coffee gets muddled with the queue for the hot dishes. Space behind the counter is cramped and, where different routes cross, inconvenient. Everybody works unrelentingly hard and remains cheerfully nice to each other through the heat and harassing customers. And everybody ends the day exhausted. I felt I had been in a trawler for eight hours. Only when one of the visitors said ‘This must be such a nice place to work,’ did I very nearly ask him if he had just landed from Mars.

Of course this restaurant finds it difficult to embrace any change. An irregular supply of vegetables from the plot, in variable volumes, is going to need an elastic frame of mind. Working in this tight and difficult environment allows no room for elasticity. I asked Ginny about this. ‘People here don’t see our side of it, our passion for it, the work and energy we put in here,’ she said.

I know you saw it the other day, how drained people are at the end of a working day. But nobody gives us credit for it. And nobody knows exactly what is needed. It is all big ideas, everybody thinks they know better than us. We are taking on board the advice that everyone seems to be giving us, but give us time.

One of the problems is that the market is moving fast. A couple of weeks ago the first salad leaves from the Sissinghurst plot were served and sold in the restaurant. They looked lovely, fresh and perfect. I had seen Amy washing them with the hose at the plot only an hour or two before. I asked a visitor, queuing there, if she realized this lettuce had been grown in the field out there. ‘Really,’ she said, half-engaged, ‘I would have thought most things in this restaurant would have been grown on the farm.’

Young people now are obsessed about feeding themselves and their children the right things. And here it is, the definition of the right thing: unbelievably local, unbelievably organic and unbelievably fresh. If it is going to continue to be successful, the restaurant has got to run with that. Soon, not growing your own will look strangely old-fashioned. The Trust knows that, Ginny knows that and has a policy to support it, but to make the change, when the change has to be made with a hungry public waiting for its lunch, is exceptionally difficult. It is clear to me now that we need a radical redesign, making the building and the kitchen all more open, easier to work, more efficient, more staff- and customer-friendly. That means more investment and yet another project but I am sure that unless it happens, the meaning of this transformation of the farm is not going to reach the public. Of course there are problems ahead. As Jonathan Light, the Trust’s area manager, says, ‘Remember: implementation is a slog.’ Ginny has some doubts that the farm could ever provide everything the restaurant needs. But that doesn’t mean to say we won’t get there in the end.

A couple of days ago, tidying up the files in my workroom, I came across a letter I wrote to my father nearly twenty years ago, in July 1989. It is entitled rather grandly ‘A Long-Term Vision for the Future of Sissinghurst’, and in it I was surprised to find this:

Central to Sissinghurst is the idea of a garden embedded in the country around it. The surroundings of the garden should not be divorced from it. There should be, in effect, a conversation between the two, a mutually sustaining relationship between the garden and the land. And one of the elements that binds them together should be a true responsiveness to the beauty and subtlety of nature.

The place should be farmed organically, I said, and Sissinghurst could become a byword not only for gardening, but for a fully integrated relationship between nature and culture, people and land, beauty and use. If we did this, I told my father, ‘it would be a way of making Sissinghurst not simply a garden with a shop and café attached but a future-looking place with a new vitality.’ I had entirely forgotten I had ever said this. Neither he nor anyone else took it up, but with it in the box file was a carbon copy of his reply. He couldn’t tell if the idea was any good but one day, ‘When The Time Comes’, I would have a chance to try these ideas out in the real world. I should wait.

Later on, I went to see Linda Clifford, James’s Stearns’s sister, Stanley and Mary Stearns’s daughter and Ossie Beale’s granddaughter. She was born in Bettenham in the 1950s, now lives in Mount Cottage on the edge of Sissinghurst Park Wood and is as much tied to this piece of landscape as anyone alive. ‘I feel as if it is my place but it is not my place,’ she said. ‘I feel I have this proprietorial interest in it, which is ridiculous, but I still want it to be a working place. Don’t mess with the land. It has got to be done right. Don’t make it a theme park. Make it properly productive again.’ I asked her how she would like to see it in 20 years’ time.

I would like to see the farm as it was in the 50s - a true mixed farm, alive and productive. It can’t be exactly like that, of course, because it won’t be the more intimate, privately farmed family enterprise it once was. And modern farming methods make different demands on the land. Quite simply, I would like to it to be doing well. That’s all. A farm doing well. And if that’s the case, then Sissinghurst will be a contented place.

Just down from her house, at the top of the Cow Field where the vegetables are now growing, a blackbird was sitting on the new gatepost shouting fearlessly about his life. To the north, the wind was blowing catspaws through the yellowing wheat. In Banky Field, on the far side of the Hammer Brook, the oats were still a blue lime-green. Along the edges of the far woods, where the oaks reach out across the headlands, the sun was making shadowed hollows, like the eyesockets in a skull. It all looked concordant, a place brimming over with its own life. Each field was as full of wheat as a saucer full of milk. Within a few years those five fields below me would be divided into eleven different compartments. Hedges would be running on the ancient lines. Peter’s new nightingale wood would be growing on the banks of the Hammer Brook. Tim and Sue’s Shorthorns would be grazing in the Old Hop Garden, their sheep in the Twelve Acres. Flowery hay would have thickened in the bottom of Frog Meadow where it had grown before for so many thousands of years. Scattered through the hedgerows, the new elms would be starting to lift into their cumulus towers above the fields. Behind me, the nut orchard of Kentish Filberts and the fruit orchard would be shady groves over grazed grass. And just here in front of me, Amy and David’s vegetable garden would be busy with the chefs and the waiters harvesting the beans and sugar snaps for the visitors’ lunch. It is not far away now. I can sit here and see it, fully alive in a way I could never have guessed or hoped for.

I realise now that, until my father died four years ago, I had remained a Sissinghurst child. I looked to it for stability and comfort, for a kind of certainty, even while not quite understanding what Sissinghurst meant or what it needed. That has changed, and Sissinghurst to me now has become less a parent than a spouse, not hovering reassuringly above me but standing alongside, with its own demands and idiosyncrasies, its own beauties and generosity, its ability to change and reluctance to do so. My relationship to it has, in other words, at last, grown up. I see it now for what it is.

I am leaving this story when it is still unfinished. There are a thousand and one steps still to take. I look at the clouds streaming away in front of me to the north-east, and that is what the future looks like too: avenues of bubbled possibilities. The future here seems just as long as the past that extends behind it. Everything that Vita and Harold responded to when they came here nearly 80 years ago is still alive, but I also remember what John Berger wrote in Pig Earth: ‘The past is never behind. It is always to the side.’ That is true. The past is everywhere around me, co-existent with present and future, soaked into this soil but not sterilizing it. There is no hierarchy. Past, present and future are all equally co-existent and Sissinghurst is becoming a place that responds to all three. And through that re-connection Sissinghurst will once again reacquire, I hope, a sense of its own middle, a confidence that it can turn to its own resources and find untold riches there. It will become, in the best possible sense of the word, its own place. That is the word, I now realize, to which this book has been devoted: place as the roomiest of containers for human meaning; place as the medium in which natural and cultural, inherited and invented, individual and communal can all fuse and fertilise. I don’t remember anything in my own life which has made me look at theworld with such a surge of optimism and hope.