Scanned and proofed by DragonAshe (aka Merithyn)

Current version: 1.0

The rolling hills continued endlessly.

Boulders were prominent; grass and trees were few.

Thee road wound thinly between the hills, frequently becoming so narrow that even the single cart was enough to block it entirely.

Just when it seemed the climbing would continue forever, the road turned down, and the seemingly endless naked rocks and dried shrubs suddenly changed to a wide awaiting vista.

While the journey had been more interesting than endless grass plains, most anyone would find the travel tiresome by the

fifth day.

From the road, tinged with a loneliness that suggested the coming winter, the voice that once sounded its delight at the undula-I ions of the stony, ocher path was now gone. Its owner was now apparently too bored to even sit on the bench of the cart; she lay instead in the bed, grooming the fur of her tail.

A young man drove the cart, apparently used to such selfish behavior on the part of his companion. The man, Kraft Lawrence, was instantly recognizable as a traveling merchant. This year made the seventh since he’d struck out on his own, and he

appeared to be around twenty-five. As if in acknowledgment of the chill that came with the deepening autumn, he tightened the fur coat that was wrapped around his body.

Occasionally, the chill also caused him to stroke his chin, covered in the sort of beard one often saw on traveling merchants, since when he sat still, he became slightly cooler. Letting a breath escape that would have turned foggy once the sun set, Lawrence glanced over his shoulder at the bed of the cart.

Normally filled to the brim with various goods, the bed was enjoying a brief respite. All that stood out was the firewood and straw that provided warmth at night, along with a single bag, small enough for a child to carry.

However, the contents of the bag were more valuable than an entire cart full of wheat would have been. The bag was full of high-grade pepper worth roughly one thousand silver trenni. If it could be sold in a mountain town, it might fetch as much as seventeen hundred pieces, but the bag was currently being used as a pillow by Lawrence’s companion, who continued lazily grooming her tail.

She was small with a face that was somehow imperious despite its apparent youth, reminiscent of a queen relaxing in her palace. The hood of her robe was thrown back, exposing her pointed ears as she attended to her tail, her expression listless.

Given the tail, the pointed ears, and the fact of her status as a merchant’s traveling companion, one might reasonably think of a dog, but unfortunately she was no dog.

She was apparently a “wisewolf,” a wolf-god from the taiga in the distant north — but Lawrence felt there was some question as to whether she could be properly called a wolf.

After all, this “wolf” appeared to be a young girl. Calling her a wolf seemed slightly inaccurate.

“We’ll be reaching the town soon. Be careful,” he said.

It would be disastrous for the girl’s ears and tail to be seen by others. The truth was, her canniness would put the instincts of even the sharpest merchant to shame, thus Lawrence didn’t need to warn her of the danger. However, she was so thoroughly relaxed that he simply had to speak up.

Not so much as glancing at him, she only yawned hugely.

Her yawn concluding with a vacant exhalation, she now nibbled puppylike on the snow white tip of her dark brown tail, as though it itched. She did not appear to have the slightest inclination to “be careful.”

Having introduced herself as a wolf and possessing these ears and this tail, Holo certainly relaxed with the carelessness of an animal, if nothing else.

“... Hrm.”

A slight vocalization that could have been a reply (or it could simply have been a small utterance of satisfaction at having conquered the itch) reached Lawrence’s ears. Tired of waiting for her reply, he looked forward again.

Holo and Lawrence had met two weeks earlier. Owing to a si range event in one of the villages Lawrence stopped at, Holo had joined him, and the two had been traveling together since. With her ears and tail, she was currently regarded as an evil spirit, and the Church sought to end her life to preserve order.

Lawrence had not a shred of doubt that she was in fact a wolf rather than a simple girl, who happened to have a wolf’s ears and a tail.

Just nine days earlier, in the river town of Pazzio, as a riot of silver chasing had come to a close, he had seen her true form.

The huge brown wolf named Holo had understood human speech and possessed an overwhelming presence that was undeniably that of a god.

Yet Lawrence believed his relationship with Holo the Wisewolf to be one of money, of partners in lending and borrowing, of companions in travel, and of friends.

He looked behind him again, and Holo appeared to be curled up in sleep. Although her legs were covered by the pants she wore under her robe, the robe was still hitched up around her waist from her earlier tail grooming, and there was no denying the fact that the sight was slightly lascivious.

Her sleeping expression was the very picture of defenselessness, and coupled with her slight form, Holo looked less like a wolf and more like the sort of girl a wolf was likely to eat.

Nevertheless, Lawrence did not take her lightly.

Her wolf ears pricked suddenly, and she stirred, pulling her hood over her head and drawing the edge of her robe down to cover her tail.

Lawrence looked ahead just as the road drew near the face of a hill and curved. Before them, the figure of a single merchant on foot could be seen.

Cautioning Holo had indeed been unnecessary.

Holo the Wisewolf was hundreds of years old, and the young man’s twenty-five years of experience were far from sufficient to make him her equal.

However, Holo looked to be the younger of the two, with her true age being many times greater than what she appeared to be, a fact that occasionally irritated Lawrence.

It was Lawrence’s hope that Holo would act more in keeping with the apparent difference between their ages, obediently minding him when she was told. A variety of problems could have been avoided this way, and the wolf would have him to thank for this — but unfortunately, the opposite was much more common.

Lawrence glanced back at the cart bed once more.

Despite the surreptitious nature of Lawrence’s backward peek,

Holo returned his look from where she lay, curled up around the bag of pepper.

She threw him a mean-spirited grin as if to say that yes, she could see everything ahead just fine, before closing her eyes once more.

Lawrence looked back to the road.

Perhaps enjoying the cart ride, Holo’s tail flicked back and forth.

The town ahead bore the strange name of Poroson.

Beyond the town to the north and east (they would travel toward towns and villages that lay many days beyond the highlands in the foreground), the dress and food of the people would change — even the gods worshipped would be different. The pair would find themselves in a truly foreign land.

Lawrence had heard that Poroson was until recently known as a gateway to another world.

Descending to the west of these rock-strewn highlands, one would find abundantly fertile, forested land in all directions. Yet I he land, hemmed in as it was by the surrounding rocks, which yielded little springwater, was difficult to farm. The only reason to take the trouble of founding a town here was its position as this gateway to another world.

They continued through the fields. Lawrence could hear the faint cries of goats through the morning haze as he counted the many gravestone-like posts he saw. The posts were carved with the names of many generations of sages in the Church’s long history and continued to purify the land even now.

Long before it was known as a gateway to another world, Poroson was a holy land to a certain pagan faith.

Many years had passed since the Church, following the will of its god, sent missionaries to convert the heathens, starting a war to purify this land tainted by impure beliefs. Poroson was a psychological turning point in the process of the destruction of the old faith. Once the Church was on the verge of wiping out the pagan faith in the area, the priests commanded that a town be founded there.

Poroson soon became the staging area for the missionaries and knights heading north and east after the remaining pagans, and it came to have a reputation as a crossroads for both goods and people.

The missionaries with their tattered, hermit-like robes and the knights with righteous swords in hand, ready to reclaim land in the name of their god, were now gone.

All that passed through the town these days were woven goods, salt, and iron from the north and east and grain and leather from the south and west. The holy wars of the past were long gone, replaced by the continuous comings and goings of shrewd merchants.

Holo’s presence made it necessary for Lawrence to take roads with little traffic, but along certain ancient trade routes, they continually passed carts laden with rare goods. Many of the textiles they saw were of particularly fine quality.

Despite the brisk trade, Poroson was rather modest, thanks to the habits of its residents. The wealth of commerce provided for a magnificent wall around the town, but the buildings within it were of humble stone construction, their roofs thatched with straw. It’s true that wherever goods and people intersect, money will be left behind and the area will prosper, but Poroson’s circumstances were slightly different.

The residents were all highly devout and gave most of their money to the Church. Furthermore, Poroson was not the holding of a particular nation, but rather of the religious capital of Ruvin-heigen to the northwest, so tithes did not stay in the town’s own church, but instead flowed to the larger city. In fact, the Church offices managed land taxes as well, so Poroson did not even control its own tax revenue.

The residents of the town had no interest in anything beyond their own humble lives.

When a bell sounded through the morning haze, the workers in the fields paused in their labors and turned to face the sound, putting their hands together and closing their eyes.

In a typical town at this hour, red-faced merchants would be busy jockeying for position in the town square, but here there was no such rude commotion.

Not wanting to intrude upon the residents’ prayers, Lawrence stopped his cart horse. Then, putting his hands together, he offered a prayer to his own god.

The bell rang a second time, and when the people returned to I heir work, Lawrence made his cart horse walk again. Suddenly, Holo spoke.

“Oh, so you are a religious man now, are you?”

“I’ll pray to anyone who can promise me safe travels and tidy profits.”

“I can promise you a fine harvest.”

Holo faced Lawrence as he glanced at her out of the corner of his eye.

“You want me to pray to you, then?”

Holo knew and hated the loneliness felt by gods. Lawrence believed she couldn’t possibly be serious, but he ventured to ask.

He suspected she was joking with him out of boredom.

As expected, her reply came in a purposefully sweet voice.

“Yes, I certainly do.”

“What shall I pray for, then?” asked Lawrence, by now used to this sort of treatment from Holo.

“Whatever you like. I can provide a bountiful harvest, naturally, but safe travels are also no problem for me. I can predict the winds and rain and tell whether springwater is good or bad. And I’m just the thing for getting rid of wolves and wild dogs.”

She sounded just like a village youth extolling his virtues to a merchant guild, but Lawrence thought for a moment before answering.

“I suppose safe travels would be worth praying for.”

“They would, would they not?” answered Holo with a self-satisfied smile, inclining her head slightly.

Seeing her carefree, innocent smile, Lawrence wondered whether she wasn’t simply trying to praise her own abilities over the god of the Church. Every once in a while, Holo exhibited a certain childishness.

“Well, I suppose I’ll ask for safe travels, then. It would be heartening to be able to avoid wolves.”

“Mm. Safe travels, is it?”

“Indeed.”

Lawrence tugged on the reins to avoid a donkey grazing on the grass.

The gateway to the town walls would be upon them soon. The end of a line of people waiting for inspection was visible even in the morning mist.

Though the entire town was part of the Church, many merchants came to it from pagan lands, so Poroson was remarkably accommodating — its inspection of goods was much stricter than its inspection of people. Lawrence was considering the tax likely to be levied on the pepper he carried when he became aware of someone looking at him from the side. There was only Holo.

“What, is that all?” Her voice sounded slightly irritated.

“Hm?”

“I am asking you if all you require is safe travel.”

Staring blankly at Holo for a few moments, Lawrence realized what she was talking about.

“What? You wanted me to put my hands together and pray?” “Don’t be ridiculous,” she said with a vexed glare. “I’m guaranteeing you safe travel — surely you don’t think that a single, useless prayer is compensation enough.”

Lawrence’s mind turned like a waterwheel as he arrived at the obvious conclusion.

“Ah, you want an offering.”

“Hee-hee-hee.” Holo gave a self-satisfied chuckle.

“What do you want?”

“Dried mutton!”

“You gorged yourself on the stuff yesterday! It must’ve been a week’s worth that you ate.”

“I’ve always room for mutton.”

Never shy, Holo licked her chops at the memory of the meat. It seemed even the noble wolf was a mere dog when presented with dried victuals.

“Cooked meat is good, too, but I simply cannot resist the texture of dried meat. If you would pray for safe travels, dried mutton is the price.”

Holo’s eyes blazed, and her tail switched restlessly underneath her robe.

Lawrence ignored this completely, instead looking at the goods loaded on the horse that was being led by the merchant in front of them. The horse’s back was piled high with a mountain of wool. “What about that wool — is it good or bad?”

Wool evidently suggested sheep. Holo looked at the mountain of wool, her eyes brimming with anticipation, before answering quickly.

“It is quite good — so good I can almost smell the grass they ate.”

“I thought as much. My pepper should fetch a good price here.” If the wool was of high quality, the meat would be excellent, too. And as the quality of meat rose, so did its price. Expensive meat made his pepper, which could be used to flavor and preserve it, all the more valuable, and Lawrence began to look forward to selling his wares.

“Also, dried meat with lots of salt is good. Just a little bit of salt will not do. Also, meat from the flanks is the best, better than meat from the legs. Here now, are you listening?”

“Hm?”

“Salted meat! From the flanks!”

“You have excellent taste. That’ll cost us.”

“Hah, ’tis a bargain at twice the price.”

It was true that some good mutton was a bargain if it meant Holo would guarantee safe travels. After all, her true form was a giant talking wolf. She could probably even protect him from the kind of ill-mannered soldiers that were hard to distinguish from out-and-out thieves.

Nonetheless, Lawrence assumed a purposefully blank expression as he regarded Holo.

Her eyes were fixed greedily upon the imagined food. He couldn’t help but tease her.

“Well, now, you must have quite a bit of money indeed. If you’ve got so much, perhaps you should repay me.”

Yet his opponent was a canny wisewolf. She soon discerned his motive.

Her demeanor tightened suddenly as she glared at him.

“That approach will no longer work.”

Apparently she had learned from the apple incident. Lawrence clicked his tongue in irritation, his face grim.

“You should’ve just asked nicely in the first place, then. It would’ve been so much more charming.”

“So if I ask charmingly enough, you will buy some for me, then?” asked Holo without a trace of charm.

Lawrence eased the horse forward as the line moved, answering flatly, “Of course not. You could stand to learn something from those cows and sheep — try chewing your cud, hm?”

He grinned to himself, proud of his wit — but Holo’s face went blank with anger, and without a word, there on the driver’s seat of the wagon, she stomped on his foot.

The road was nothing more than hard-packed dirt, the simple houses made of rough-hewn stone and thatched with grass.

The people of Poroson bought nothing but the barest necessities from the merchant stalls, so there were surprisingly few such stalls.

A goodly number of people moved about the town, among them merchants with carts or backs fully loaded, but the atmosphere seemed to suck up the normal town chatter like cotton, so it was oddly quiet.

It was hard to believe this quiet, simple, proud town was a nexus of foreign trade that earned dizzying amounts of money every day.

After all, missionaries whose street-corner sermons went largely ignored in other cities could count on gratefully attentive crowds here — so how was profit so effectively made?

To Lawrence, the town was nothing less than a mystery.

“’Tis a tedious place,” came Holo’s assessment of the uniquely religious town.

“You’re only saying that because there’s nothing to eat.”

“You speak as though I think of nothing else.”

“Shall we take in a sermon, then?”

Just ahead of them, a missionary preached to a crowd, one hand on a book of scripture.

The listeners were not only townspeople — there were several merchants whose prayers were normally for naught but their own profit.

Holo regarded them distastefully and sniffed.

“He’s about five hundred years too young to be preaching to me.”

“I daresay you could stand to hear a sermon on frugality.”

Toying idly with the silken sash at her waist, Holo put her hand to her mouth and yawned at Lawrence’s suggestion. “I’m a wolf yet. Sermons are complicated and difficult for us to understand,” she said shamelessly, rubbing her eyes.

“Well, as far as the teachings of the god of frugality go, they’re more persuasive here than anywhere else, I’d reckon.”

“Hm?”

“Nearly all the money made here flows to the seat of the Church northwest of here, Ruvinheigen — now there’s a place I’ve no desire to hear a sermon.”

The Church capital of Ruvinheigen was so prosperous some said its walls had turned to gold. The upper echelons of the Church Council that controlled the region had turned to commerce to support their subjugation of the heathens, and the priests and bishops of Ruvinheigen put the merchants to shame.

Lawrence wondered if that was precisely why opportunities for profit there were so absurdly plentiful.

Just then, Holo tilted her head quizzically. “Did you say Ruvinheigen?”

“What, do you know it?” Lawrence gave Holo a sidelong glance as he steered the wagon to the right once the street forked.

“Mm, I remember the name, but not as a city—it was a person’s name.”

“Ah, you’re not wrong. It’s a city now, but it was the name of a saint who led a group of crusaders against the pagans. It’s an old name — you don’t hear it much anymore.”

“Hmph. Maybe ’tis him I’m remembering.”

“Surely not.”

Lawrence laughed it off but soon realized — Holo had set out on her travels hundreds of years ago.

“He was a man with flaming red hair and a great bushy beard. I le’d hardly gotten a glance at my lovely ears and tail before he set his knights after me with spear and sword. I’d had enough, so I took my other form and kicked his knights around before si nking my teeth into that Ruvinheigen’s backside. He was rather lean and far from tasty.”

Holo sniffed proudly as she related the gallant tale. The surprised Lawrence had no response.

In the holy city of Ruvinheigen, there were records of Saint kuvinheigen having red hair and the city itself having originally been a fortress that fought against pagan gods.

However, in his battles against the heathen deities, Saint Ruvinheigen was said to have lost his left arm. That is why on the great mural in the city cathedral he was pictured with no left arm, his ragged clothing smeared with blood, resolutely ordering his crusaders forward against the pagans, the protection of God at their backs.

Perhaps the reason Saint Ruvinheigen was always pictured in clothes so ragged he might as well be nude was because Holo had shredded them. Her true form was that of a massive wolf, after all. It was easy to imagine her bloodying someone after a bit of sport.

I f what Holo said was true, Saint Ruvinheigen had probably been ashamed of being bitten on his rear and had omitted that bit from the story. In that case, the tale of the saint losing his left arm was pure fabrication.

Had Holo bitten the real Saint Ruvinheigen?

Hearing the story behind the history, Lawrence chuckled.

“Oh, but wait a moment —,” said Holo.

“Hm?” “I only bit him, I’ll have you know. I did not kill him,” said Holo quickly, anticipating Lawrence’s reaction.

For a moment, Lawrence didn’t understand what she was getting at, but soon he realized.

She must have assumed he would be angry if she killed one of his fellow humans.

“You’re considerate at the strangest of times,” said Lawrence.

“’Tis important,” said Holo, her face serious enough that Lawrence capitulated without any further teasing.

“Anyway, this surely is a tedious city. The middle of the forest is livelier than this.”

“I’ll unload my pepper, pick up a new commodity, and we’ll be on our way to Ruvinheigen, so just bear it until then.”

“Is it a big town?”

“Bigger even than Pazzio — more properly a city than a town really. It’s crowded, and there are lots of shops.”

Holo’s face lit up. “With apples even?”

“Hard to say if they’ll be fresh. With winter coming, I’d think they’d be preserved.”

“...Preserved?” said Holo, dubious. In the northlands, salt was the only method of preservation, so she assumed preserved apples would also use salt.

“They use honey,” said Lawrence.

Pop! went Holo’s ears, flicking rapidly under the hood she wore.

“Pear preserves are good, too. Also, hmm, they’re a bit rare, but I’ve seen preserved peaches. Now those are fine goods. They slice the peaches thin, pack them in a cask with the odd layer of almonds or figs, then fill up the spaces with honey, and seal it shut. Takes about two months for it to be ready to eat. I’ve only had it once, but it was so sweet the Church was considering banning the stuff... Hey, you’re drooling.”

Holo snapped her mouth shut as Lawrence pointed it out.

She took a nervous glance around, then looked back at Lawrence dubiously. “You... you’re toying with me, though.”

“Can’t you tell if I’m lying or not?”

Holo set her jaw, perhaps at a loss for words.

“I’m not lying, but there’s no telling whether they’ll actually have the preserves. They’re mostly for rich nobles, anyway. The stuff isn’t just lined up in a shop.”

“But if it is?”

Swish, swish — Holo’s tail was switching back and forth beneath her robe so rapidly it almost seemed like a separate animal altogether. Her eyes were moist and blurred with overflowing anticipation.

Holo’s face was so close to Lawrence that she rested her head on his shoulder.

Her eyes were desperately serious.

.. Fine, fine! I’ll buy you some!”

Holo gripped Lawrence’s arm tightly. “You have to!”

He felt that if he looked sideways at her, he’d be bitten on the spot.

“A little, though. Just a little!” Lawrence said. It was not clear if Holo was listening or not.

“That’s a promise, then! You’ve promised!”

“Okay, okay!”

“So let us hurry on, then! Hurry, now!”

“Stop grabbing me!”

Lawrence shrugged her off, but Holo’s mind had wandered elsewhere. She seemed to look off into the distance and muttered .is she nibbled on the nail of her middle finger.

“'They may sell out. Should it come to that...”

Lawrence was beginning to regret having said anything about honeyed peach preserves, but it was too late for such regrets. If he

dared to suggest he had decided not to buy any after all, it seemed likely she’d tear out his throat.

It didn’t matter that honeyed peach preserves weren’t something that traveling merchants could afford.

“It’s not a question of selling out — they may not have any at all,” Lawrence said. “Just understand that.”

“We are talking about peaches and honey, sir! It beggars belief. I’eaches and honey.”

“Are you even listening to me?”

“Still, it’s hard to give up pears,” said Holo, turning to Lawrence and looking up at him.

Lawrence’s only reply was to heave a long-suffering sigh.

Lawrence planned to sell his pepper to the Latparron Trading Company, whose name was every bit as odd as the town in which it was located — Poroson.

If one were to trace the name, it would surely hearken all the way back to the time before Poroson was a town and only pagans inhabited the area. The strange names were all that remained of the past, though. After all, everyone here was a true believer in the Church, from the tops of their heads to the tips of their toes.

The Latparron Company would soon have its fiftieth master, and each seemed to be more devout than the last.

Thus it was that no sooner had Lawrence called upon the company—which he’d not visited in half a year — than he was regaled with praise for the newly arrived priest, whose sermons he simply had to hear, as would they not save our very souls?

Still worse, the master of the Latparron Company seemed to take Holo in her robes for a nun on pilgrimage and exhorted her to minister to Lawrence as well.

Holo took the opportunity to rail at Lawrence at length, occa-■aonally grinning in a way that only he could see.

After some time, their preaching ended, and Lawrence swore to himself that he wouldn’t spare so much as a single coin for any honeyed peach preserves.

“Well, then, that went a bit long, but shall we talk business now?”

“I await your pleasure,” said Lawrence, clearly tired — but the Latparron master had put on his business face now, so Lawrence couldn’t let his guard down.

It was possible that the master’s lengthy sermon was a tactic to wear his opponents down, making them easy prey.

“So, what goods have you brought me this day?”

“Right here,” said Lawrence, regaining his composure and bringing out the pepper-stuffed sack.

“Oh, pepper!”

Lawrence kept hidden his surprise at the master’s correct guess of the bag’s contents. “You know your goods,” he said.

“It’s the smell!” said the master with a mischievous smile — but Lawrence knew pepper yet to be ground has little scent.

Lawrence stole a sidelong glance at Holo, who looked on amused.

“It seems I’m still a novice,” said Lawrence.

“Just a matter of experience,” said the master. As far as Lawrence could tell from the man’s broad, easy manner, his mistaking Holo for a nun might also have been an act.

“Still, Mr. Lawrence, you always bring the best goods at the most opportune time. By God’s grace, the hay grew well this year, and the pork has gotten fat merely walking the streets. Demand for pepper will be high for a while. Had you gotten here even a week sooner, I’d have been able to take it off your hands for a pittance!”

Lawrence could only offer a pained smile in response to the cheerful man. The Latparron master had taken complete control of the conversation. He could now use strong-arm negotiating lactics. It would be hard for Lawrence to regain the upper hand.

Traders like these in small companies were why the life of the merchant was a hard one.

“Right, then, let’s take its measure. Have you a scale?”

Unlike the money changers whose reputations depended on the accuracy of their scales, the scales that merchants carried were doctored as a matter of course. With commodities like pepper or gold dust, a small “adjustment” to a scale’s gradations could make a large difference, so both buyer and seller weighed items on their own scales.

However, it wasn’t every day that Lawrence dealt with high-priced goods like pepper, so he had no scales.

“No, I don’t have a scale — I trust in God.”

The master smiled and nodded at Lawrence’s reply. There were I wo sets of scales on a shelf, and he deliberately brought out the set farther away.

Though he was careful not to show it, Lawrence internally sighed in relief.

Be he the most devout, faithful follower of the teachings of the Church, a merchant was still a merchant. Undoubtedly the first set of scales had been doctored. If Lawrence’s pepper was weighed on such scales, there was no telling how much of a loss he might sustain. It could be as bad as a silver piece for every peppercorn.

Lawrence gave God his thanks.

“Even if you believe in a just God, man should be able to discern whether the scripture before him is true or false. A righteous man still trespasses against God if he commits to memory false scripture, after all,” said the master, setting the scales down on a nearby table.

He was probably trying to reassure Lawrence that his scales were accurate.

Although merchants were always trying to outsmart one another, that didn’t mean trust was never necessary.

“If you’ll excuse me for a moment,” said Lawrence, at which point the master nodded and took a step back.

On the table was a beautiful set of brass scales, which gleamed a dull gold. It was the sort of set one would expect to see in the offices of a wealthy cambist in a large city and seemed a bit out of place in this shop.

The Latparron Trading Company’s storefront was so plain it was easily mistakable for a simple home, and the only employees were the master and a few men. The interior of the shop was also plainly furnished with two shelves situated against the wall, one holding jars that seemed to contain spices or dried foodstuffs and another holding bundles of documents, paper, and parchment.

While the scales seemed not in keeping with the rest of the shop, the balance of those scales was clear.

The scales balanced in the center with plates of counterweights to the left and right.

They did not seem to have been tampered with.

Relieved, Lawrence looked up and smiled. “Shall we proceed to weigh the pepper, then?”

There was no reason not to.

“Let’s see, we’ll need paper and ink. Wait just a moment, please,” said the master, walking to the corner of the room and retrieving an ink pot and paper from the shelf. Lawrence was idly looking on when a tug at his sleeve pulled him out of his reverie. There was no one else there — it was Holo.

“What is it?”

“I’m thirsty.”

“You’ll have to wait,” said Lawrence shortly — but he immediately reconsidered.

She was Holo the Wisewolf after all. She wouldn’t make a complaint like that out of the blue. There had to be some kind of reason behind it.

Having changed his mind, Lawrence was about to ask her to explain herself when the master spoke again.

“Even the saints themselves needed water to live. Would you like water or perhaps wine?”

“Water, if you please,” said Holo with a smile. Evidently she had only been thirsty after all.

“Just a moment, then.” The master left the contract paper, ink, and quill on the table and walked out of the room, going to fetch the water himself.

In this regard he seemed to be no merchant, but the model of a devout adherent of the Church.

Yet even as Lawrence was impressed at the master’s faith, he gave Holo a sidelong glare.

“I know this may seem like nothing to you, but to us merchants this is a battleground. You could have had as much water as you wanted later.”

"But I am thirsty,” said Holo, looking away stubbornly—she hated being scolded. Despite her frightening intelligence, she could be strangely childish at times. There was no point in saying anything more.

Lawrence sighed, and to chase away his frustration with Holo, he set his mind on estimating how much pepper he had.

At length the master returned, carrying a wooden tray with an Iron pitcher and cup. Lawrence’s shame at having made a business associate and an elder perform such a menial task was very real, but the master’s smiling face seemed to have dispensed with business for the moment.

“Well, then, shall we proceed with the weigh?”

"Indeed.”

They began to weigh the pepper as Holo looked on, leaning against a wall a short distance away, iron cup clasped between her hands.

The weigh was a simple enough task, with a set weight being prepared on one side of the scales and the other being loaded with pepper until it balanced.

It was simple, but if one grew tired of seeing the counterweight sink and was tempted to call it good enough and proceed to the next load, a merchant could unwittingly sustain a significant loss.

So both the master and Lawrence carefully balanced each load until each was satisfied before proceeding to the next.

For all its simplicity, the weighing was sensitive work, and it took forty-five loads to finish. Pepper varied depending on its origin, but a load of Lawrence’s product balanced roughly with a single counterweight should have been worth about one gold lumione piece. Based on his most current knowledge of exchange rates, one lumione equaled thirty-four and two-thirds trenni, the silver coin commonly used in the port town of Pazzio. Forty-five loads at that rate would come to 1,560 trenni.

Lawrence had bought the pepper for a thousand trenni, so that meant a profit of 560 pieces. The spice trade was indeed delicious. Of course, gold and jewels — the raw materials for luxury goods — could fetch two or three times their initial purchase price, so this was a meager gain in comparison, but for a traveling merchant who spent his days crossing the plains, it was profit enough. Some merchants would haul the lowest-quality oats on their very backs, destroying themselves as they crossed mountains, only to turn a 10 percent profit when they sold in the town.

Indeed, compared with that, clearing more than five hundred silver pieces by moving a single light bag of pepper was almost too savory to believe.

Lawrence grinned as he packed the pepper back into its leather sack.

"Right, that’s forty-five measures’ worth, then. Where does this pepper come from?”

"It was imported from Ramapata, in the kingdom of Leedon. Here’s the certificate of import from the Milone Company.”

"From Ramapata, then? It’s come quite a ways, then — I can ■■scarcely imagine the place,” mused the master, narrowing his eyes and smiling as he took the certificate parchment Lawrence offered him.

Town merchants often spent their entire lives in the villages of their birth. There were some who would go on pilgrimages after their retirement, but there was no time for such things when they were actively working.

However, even Lawrence the traveling merchant knew little of the kingdom of Leedon, save that it was famous for its spices. To get there from Pazzio, one had to take the river all the way to the coast and then board a long-distance sailing ship south across two separate seas, a journey of roughly two months.

The language was different, of course, and apparently it was hot like summertime year-round in Leedon, and the population was permanently tanned near black from the time they were horn.

It seemed unbelievable, but there was spice, gold, silver, and iron that supposedly came from the place, and the Milone Company vouched for the origin of the pepper, which the certificate claimed was Ramapata.

Was it a real country?

“The certificate seems authentic,” said the master.

The kinds of bills of exchange, trusted promissory notes and contracts that passed through town merchants were huge. Sup- posedly they could even recognize bills signed by small companies in faraway lands to say nothing of huge organizations that had their main branches in a foreign country.

Recognizing the seal of a company as large as Milone would be but the work of a moment. Signatures were important, but the soul of a contract was the seal.

“Right, then, it’ll be one lumione per measure. Will this do?” “Can you tell me what the lumione is trading at currently?” Lawrence asked suddenly, even though he had some grasp of the coin’s market value.

Gold coin was generally used as an accounting currency — that is to say it was the basis for calculating the values of the many other currencies in the world. Calculations were performed in gold currency and then remitted in other, more convenient forms. Of course, in that situation the market value of the currency in question became an issue.

Lawrence was suddenly very nervous.

“Mr. Lawrence, as I recall, you follow the path of Saint Metro-gius in business, like your teacher did, correct?”

“Yes. Perhaps it’s the protection of Saint Metrogius that’s kept my travels safe and my business sound.”

“So I presume that you’ll take payment in trenni silver?”

Many traveling merchants wanted to repeat the successes of the past, and so rather than move randomly from one town to another, they trod the paths of the saints of old.

Thus it was that the currency they used at a given time was quite predictable.

For the master of the Latparron Trading Company to come to that conclusion so quickly meant he was very shrewd merchant indeed.

“In trenni silver,” he continued, “the current rate is thirty-two and five-sixths.”

The rate was lower than Lawrence remembered. But given this town’s importance as a trade center, it was within the realm he could allow.

In places where currencies from many different places all converged, the exchange rate with respect to accounting currencies tended to be lower.

Lawrence did the calculations in his head at lightning speed. At this rate he’d get 1,477 trenni for his pepper.

ihe amount was less than he’d anticipated but a tolerable price nonetheless. It would be a huge step toward realizing the dream of opening his own shop.

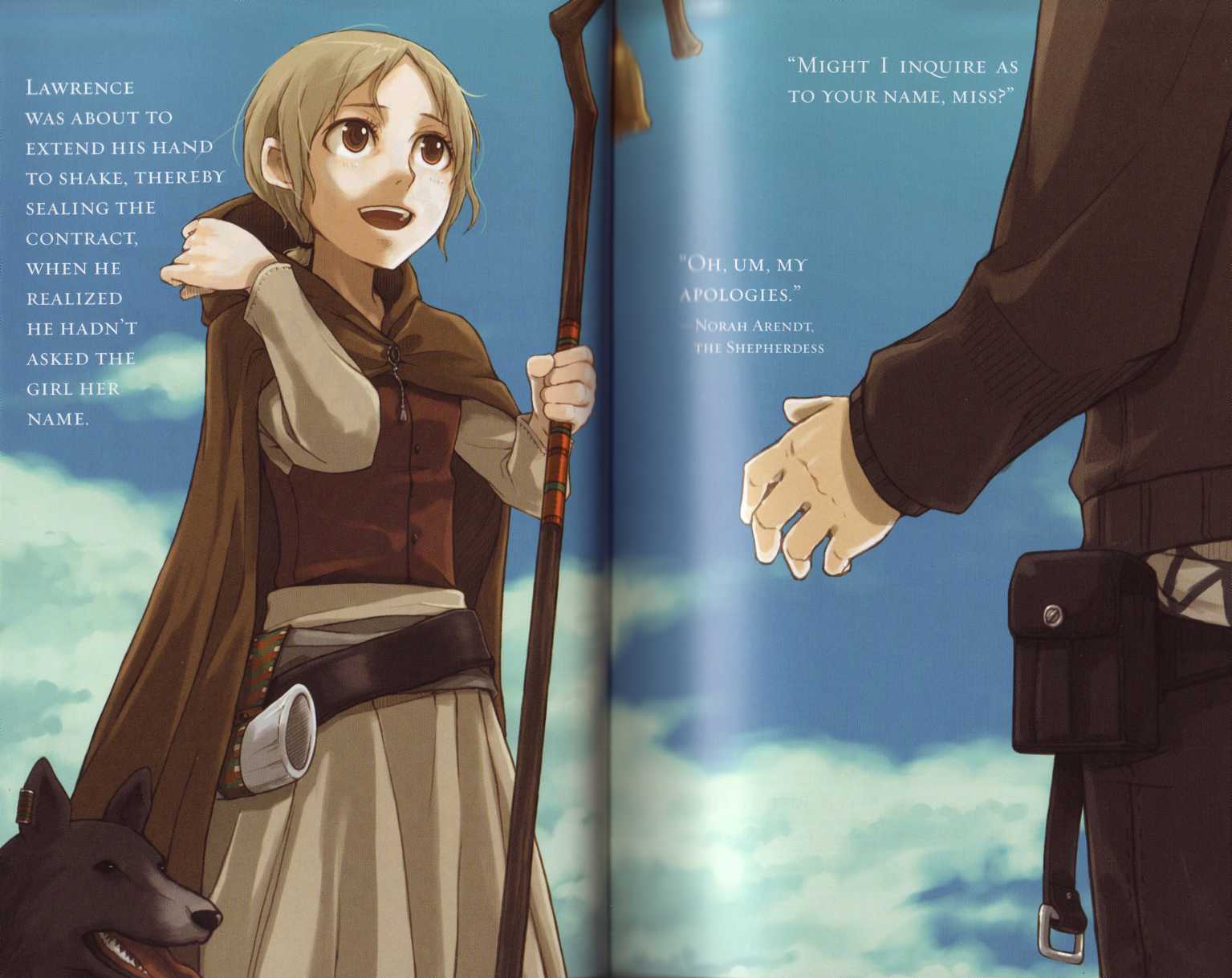

He took a deep breath and extended his right hand toward the master. “That price will be fine, sir.”

The master’s face broke into a smile, and he accepted Lawrence’s hand. A merchant’s spirits were never better than at the moment of a successful contract.

This was one such moment.

“Ughh...” Holo cut in with a listless voice.

“Whatever is the matter?” asked the master worriedly as he and Lawrence looked to Holo, who leaned unsteadily against the wall.

In that instant, Lawrence remembered the sale of his furs to the Milone Company and grew suddenly nervous.

Ihe master of the Latparron Company was a canny merchant who managed his shop alone. Trying to outwit him was likely to end badly. Having Holo around didn’t mean they had to try to trick their trading partners every single time.

Even as Lawrence thought this, he stopped short. Holo was acting strangely.

“U-ugh... I’m, I’m dizzy...”

Holo held on to the cup as her unsteadiness grew worse, and the water seemed like it would spill out at any moment.

The master walked up to her, looking worried as he stilled the cup and supported her slim shoulders.

“Are you recovered?”

“...A bit. Thank you,” said Holo weakly, finally standing straight again with the master’s help.

She looked every bit the fasting nun suffering from a bout of anemia. Even someone who wasn’t as devout as the master would have wanted to help her, but Lawrence noticed something strange.

Underneath Holo’s hood, her wolf ears had not drooped very much.

“A long journey will tire even the strongest man,” declared the master.

Holo nodded slightly, then spoke. “I may well be tired from the travel. My vision seemed to tilt suddenly...”

“That won’t do. Ah, I have it — shall I bring some goat milk? It’s fresh from yesterday’s milking,” he said, offering her a chair and briskly going to fetch the milk without waiting for her response.

Lawrence was surely the only one who had any premonition that Holo was going to do something else when she did not sit in the offered chair and instead went to set the iron cup on the table.

“Sir,” she said to the master, whose back was turned. “I believe I am yet a bit dizzy.”

“Heavens. Shall I call a physician?” asked the master, looking over his shoulder with heartfelt concern.

Underneath the hood, Holo’s expression was anything but the weak dizziness she feigned.

“Look here. It’s tilting before my very eyes,” said Holo, taking the cup and spilling a few drops on the surface of the table — whereupon it flowed smoothly to Holo’s right and off the edge of the table, dripping to the floor with a small plip sound.

“Wha —!” Lawrence walked swiftly to the table and put his hand on the scales.

It was the same set of scales he’d so carefully gauged the accuracy of earlier. If they were even slightly off, it would mean a large loss for him, and so he’d checked the scales’ accuracy carefully— but they aligned perfectly with the direction in which the water had flowed off the table.

This led to a single conclusion.

rIhe weighing was over, and the plates of the scale were empty save for the counterweights on them. Lawrence took the set of scales and rotated it to face precisely the opposite direction.

The scales tipped this way and that owing to the sudden movement, but when set back on the table, their movement slowed and eventually stopped.

According to the gradations, the scales balanced perfectly— despite the incline of the table. If they had been accurate, the reading would have been skewed by the slant of the table.

The scales had clearly been tampered with.

“So, then, did I drink water, or was it wine?” inquired Holo. She looked back to the master — as did Lawrence.

The master’s expression froze, and sweat appeared on his forehead.

“What I drank was wine. Was it not?” Holo’s voice sounded so a mused that even her smile was practically audible.

The master’s face paled to a nearly deathly pallor. If the fact

Ithat he used fraudulent scales to swindle merchants was made public in a god-fearing town like this, all his assets would be forfeit, and he would face instant bankruptcy.

“There’s a saying that ‘no one drinks less than the master of a full tavern’ —this must be what that means,” said Lawrence.

The stricken master was like a cornered hare, unable to cry out even as a predator’s fangs pierced its skin.

Lawrence walked back toward the master with an easy smile.

“The secret to prosperity is being the only sober one, eh?”

So much sweat beaded up on the master’s forehead that you could trace a picture in it.

“It seems I’m drunk on the same wine as my companion. I doubt we’ll be able to remember anything we’ve seen or heard in here... though in exchange I may be a bit unreasonable.”

“Wh-what do you... ?” The master’s face shivered in fear.

Taking easy revenge here would be failing as a merchant, though.

There wasn’t even a mote of anger at being deceived in Lawrence’s mind.

All he thought of were cold calculations of how much more profit he could extract from his opponent’s fear.

This was an unexpected opportunity.

Lawrence drew near the man, his expression still smiling, his tone still every bit the negotiating merchant.

“Let’s see... I think the amount we agreed to, plus the amount you were going to gain, plus, oh... you’ll let us buy double on margin.”

Lawrence was demanding to be allowed to buy more than he had the cash to secure. It’s self-evident that the more money a merchant can invest, the greater profit he can realize. If he can buy two silver pieces’ worth of goods with a single piece, he will double his profit, pure and simple.

But to buy two pieces’ worth with one piece, he would obviously need collateral. Since the merchant is essentially borrowing money, the lender has the right to demand collateral from the borrower.

However, the master was in no position to make such a demand, which is why Lawrence pushed such an unreasonable position. It’s a third-rate merchant that doesn’t take advantage of weakness.

“I, uh, er, I can’t possibly...”

“You can’t do it? Oh, that’s a shame... I’m feeling significantly less drunk.”

The master’s face was so wet it seemed to nearly melt as the sweat mixed with tears.

His face a mask of despair, he slumped, defeated.

“As for the goods, let’s see. Given the amount, perhaps some high-quality arms? Surely you have lots of goods bound for Ruvinheigen.”

... Arms, you say?”

The master looked up, seeming to see a glimmer of hope. He had probably been assuming that Lawrence never planned to pay him back.

“They’re always a good bet for turning a tidy profit, and I can get the loan back to you quickly that way. What say you?”

Ruvinheigen served as a resupply base for the efforts to subjugate the pagans. Any items that served in the fighting flew off the shelves year-round. It was difficult to sustain depreciation losses when selling such goods.

Since Lawrence would be able to purchase double the normal amount on margin, he’d have double the insurance against depre-ciation, which made weapons a good choice for a margin buy.

The master’s face shifted to that of a shrewdly calculating mer- chant. “Weapons... you say?”

“Since I’m sure there’s a trading company in Ruvinheigen with connections to yours, selling them there will balance out the books.”

In short, after Lawrence sold the weapons he bought with money borrowed from the Latparron Company to another company in Ruvinheigen, he wouldn’t have to come all the way back to Poroson to return the money.

In certain situations, the give-and-take of money could be accomplished with nothing more than entries in a ledger.

It was the great triumph of the merchant class.

“What say you?”

At times, the business smile of a merchant could be an intimidating thing. Even among such smiles, Lawrence’s was exceptionally intimidating as he cornered the manager of the Latparron Trading Company, who — unable to refuse — finally nodded.

“My thanks! I’d like to arrange for the goods immediately, as I hope to depart for Ruvinheigen very soon.”

“U-understood. Er, as for the valuation...”

“I shall leave that to you. After all, I trust in God.”

The master’s lip twisted bitterly in what must have been a pained smile. It was unavoidable that he’d appraise the weapons rather cheaply.

“Are you two quite finished?” said Holo, guessing that the strong-armed “negotiation” was over. The master gave a sigh of dismay. It seemed there was still one person who wanted a say.

“I daresay my drunkenness is lifting as well,” said Holo, her head tilted charmingly to one side — but she must’ve seemed like a devil to the master.

“Some fine wine and mutton would do much for my spirits. Make sure the mutton’s from the flanks now!”

The master could only nod his head at her casual imperiousness.

“Make it quick now,” said Holo, partially in jest, but hearing these words from the girl who adroitly saw through his doctored scales, the master turned around and scampered from the room like a pig smacked on the rear.

One couldn’t help but feel the master was overdoing it a bit, but if his fraud was made public, he would be ruined. To that extent, a little bowing and scraping was a small price to pay.

Lawrence would have taken a huge hit to his own assets if the trick hadn’t been noticed.

“Hee-hee. Poor little man,” said Holo with a delighted chuckle that made her seem even nastier.

“You’ve certainly a keen eye, as usual. I didn’t notice a thing.”

“I’m beautiful and my tail fur is sleek, but my eyes and ears are also keen. I noticed the moment we entered the room. I suppose he would’ve been sly enough to fool the likes of you, though,” said Holo, sighing and waving her hand dismissively.

Lawrence would have been happier if she’d said something ■ooner, but the reality was he had not noticed the fraud, and the fact that Holo did had turned a great loss into a great gain.

It wouldn’t kill him to be polite.

“I’ve nothing to say for myself,” Lawrence admitted. Holo’s eyes twinkled at his unexpected meekness.

“Oh ho! I see you’ve matured a bit.”

Lawrence — indeed having nothing to say for himself — could only smile, chagrined.

There is something known as “spring fever.”

It is most common during the winter in places far from rivers or seas. The streams freeze, and people survive on salted meat and stale bread day in and day out. It’s not that no vegetables can survive the frost, but rather that such produce is better sold than eaten. Eating the produce does nothing for the chill, but with the money gained from its sale, firewood can be bought and furnaces stoked.

Rating naught but meat and drinking nothing but wine takes its toll, and by spring, many have broken out in rashes.

This is spring fever, and it is proof of neglect for one’s health.

Naturally it is well-known that resisting the temptation of meat and the comfort of wine will spare one this fate. Eat vegetables and meat only in moderation — such will the Church’s sermon be every Sunday.

Thus come spring, the sufferers of spring fever will often find themselves being terribly scolded by the priest. Gluttony is, after all, one of the seven deadly sins — whether or not the glutton knows it.

Lawrence heaved a long-suffering sigh at Holo’s overindulgence.

She burped. “Whew... that was tasty.” She was in high spirits after washing down the fine mutton with some fine wine.

Not only was it all free of charge, but after eating and drinking her fill, she could curl up in the wagon bed for a nap.

Even the most extravagant merchant will, as a matter of course, think ahead and limit his excesses, but not Holo.

Tapping her feet in delight, she had eaten and drunk with glee and only stopped to take a break.

Lawrence reckoned that if it had been their travel provisions, she would’ve eaten three weeks’ worth — and she drank so much wine he began to wonder where it was going.

If she had turned around and sold the food she extorted from the Latparron master, she would have put a big dent in her own debt to Lawrence.

This was yet another reason Lawrence was stunned.

“Now, then, I daresay I’ll take a nap,” said Holo.

Lawrence didn’t even bother to look at the source of this exemplar of depravity.

In addition to squeezing some fine wine and mutton from the Latparron Company master, Lawrence had obtained a large load of arms at a very reasonable price. He and his companion left the town of Poroson without so much as waiting for the noontime bells. Little time had passed since then, and the sun was just now overhead.

With the clear skies and warm sunshine, it was perfect weather lor a midday drink, followed by a nap.

Owing to the load, the wagon bed was in a state of disarray, but with wine enough in her, Holo probably wouldn’t mind.

The trade road that they took to Ruvinheigen was full of steep inclines and sudden turns just outside of Poroson but smoothed out and gave a grand view as it slowly descended.

The road meandered on.

It was well traveled, which made for a firmly packed surface with holes being quickly filled.

liven though her “bed” was packed full of sword hilts, Holo was easily able to nap on top of them and pass the afternoon away since the road was so smooth.

Then there was Lawrence, who had drunk no wine and spent the day looking at a horse’s backside, reins in hand. His jealousy made it easy for him not to look at Holo.

“Mm, I ought to tend to my tail,” said Holo — her tail the only thing she was diligent about. She pulled it out of her robes without a hint of concern.

Not that any was warranted; the expansive view meant there was no danger of being surprised by an approaching traveler.

Holo began to comb her tail, occasionally picking a flea out or pausing to lick the fur clean.

The care she took with her tail was visible in her silent, single-minded attention to the job.

She worked from the very base of the tail, which was covered in dark brown fur, finally reaching its fluffy white tip, and then suddenly looked up. “Oh, that’s right.”

“...What?”

“When we get to the next town, I want oil.” “...Oil?”

“Mm. I’ve heard it would be good to use on my tail.”

Lawrence turned away from Holo wordlessly.

“So will you buy some for me?” asked Holo with a charming smile, her head tilted.

Even a poor man would be hard-pressed to resist that smile, but Lawrence only glanced at her out of the corner of his eye.

Figures larger than her smile danced before his eyes — specifically, the debt she owed him.

“The clothes you’re wearing now, plus the extras, the comb, the travel fee, the wine and food — have you added them all up? There’s the head tax when we enter a town, as well. Surely you’re not telling me you can’t do sums,” said Lawrence, mimicking Holo’s tone, but Holo still smiled.

“I can surely do sums, but I’m still better at subtraction,” she proclaimed, then laughed at some private amusement.

Lawrence knew she was hiding some kind of comeback, but her manner was strange. Perhaps she was still drunk.

He glanced at the wineskins that lay in the wagon bed. They’d taken the Latparron master for five skins of wine, two of which were now empty.

It wasn’t impossible that she was drunk.

“Well, perhaps you should try adding up all you’ve used. If you’re such a wise wolf, you should be able to work out my answer from that.”

“All right, I shall!” said Holo with a smile and a cheerful nod.

Just as Lawrence looked forward again, thinking how nice it would be if she were always so agreeable, Holo continued.

“You will definitely buy me some,” she said.

Lawrence cast his eyes askance to spy her grinning at him. Maybe she really was drunk. It was a very charming smile.

“Just look what happens to the wits of the proud wisewolf when she has too much wine,” muttered Lawrence to himself. Holo’s head flopped from one shoulder to the other.

If she fell drunkenly out of the wagon, she could be injured. Lawrence reached out to steady her slim shoulder, and Holo grabbed his hand with a quickness that was nothing short of wolflike.

Surprised, Lawrence looked into her eyes. She was neither drunk nor laughing.

“After all, it’s thanks to me that your wagon bed was so cheaply lilled. You’ll pull in a tidy profit.”

Her charm had vanished.

“O-on what basis — ”

“I won’t have you belittle me. Surely you don’t think I missed you strong-arming that master? I’ve a sharp mind, keen eyes, aye; hut don’t forget, my ears are good, too. I couldn’t have missed your negotiations.” Holo grinned unpleasantly, showing her langs. “So you’ll buy some oil for me, yes?”

In fact, Lawrence had taken advantage of the master’s weakness during his negotiations, and it was also true that things had gone just as Lawrence had hoped.

He cursed himself for being so obviously pleased upon signing the contract. Once it was known that someone was going to make a lot of money, they were obvious targets for sponging and wheedling — it was human nature.

“Uh, er, well, how much do you think you’re in debt to me for?

It’s one hundred forty silver! Have you any idea how much money that is? And now you think I’m going to spend more on you?”

“Oh? What, you want me to pay you back?” Holo looked at Lawrence with an expression of mild surprise, as if to say she could pay him back at any time she chose.

There are none in this world who don’t wish to be paid back money they have lent. Lawrence gritted his teeth and glared at Holo, enunciating his response very carefully. “Of. Course. I. Do.”

If Holo paid back what she owed in a lump sum, he’d be able to fill his wagon bed with more and better goods, which would mean improved profits. More investment equaled greater return — it was at the very center of a merchant’s world.

Yet Holo’s expression changed completely at Lawrence’s words. She regarded him coldly, as if to say, “Oh, that’s how it is.”

Lawrence faltered at the completely unexpected change.

“So that’s how you’ve been thinking,” said Holo.

“Wh-what do you — ”

Lawrence would have finished with mean, but Holo’s rapid-fire response cut him off.

“Well, I suppose if I pay my debts, that makes me a free wolf. I see. I’I'll just pay you back, then.”

Hearing these words, Lawrence understood what Holo wanted to say

Some days earlier, during a disturbance in Pazzio, Lawrence had seen Holo’s wolf form and retreated in fear. Deeply hurt, Holo tried to leave Lawrence, but Lawrence stopped her by saying he would follow her all the way to the north country to collect the money she owed him for destroying his clothes.

“Come what may, you’ll pay me back,” he had said. “So leaving me now won’t get you anything.”

Holo stayed with Lawrence based on the reasoning that making him come all the way out to the north country would be a bother, and Lawrence had thought that the business about debt repayment was just a pretense for both of them.

No, he’d believed it.

He believed that even if she were to repay the debt, she would still wish for him to travel with her to the forests of the north country—though her bashfulness would prevent her from admitting it.

And Holo had now turned the tables on him. She used the fact that the debt was his own pretense against him.

A single word jumped into his mind.

Unfair. Holo was truly unfair.

“In that case, I’ll just give your money back and hie myself north, shall I? I wonder how Paro and Myuri are faring.”

Holo looked away, purposefully letting a small sigh escape.

Lawrence, at a loss for words, glared sourly at the wolf girl that sat beside him and wondered how to retort.

He imagined that if he was stubborn and demanded that she pay him now and go on her merry way, Holo would really do it — and that wasn’t what Lawrence wanted. This was where he’d have to cry uncle.

There really wasn’t anything charming about Holo.

Lawrence stared at her, furiously trying to think of a comeback, but Holo looked away from him obstinately.

Some time passed.

“... We didn’t decide the due date for repayment. Just as long as I get it by the time we arrive in the north country. Will that do?”

Some part of Lawrence was still stubborn. He simply couldn’t let the cheeky wolf girl have everything she wanted. This was as far as he could give in.

Holo seemed to understand that. She slowly turned toward him and smiled, satisfied.

“I should think I’ll be able to repay you by the time we’ve arrived in the north country,” she said purposefully, drawing near him. “And it’s my intention to pay you back with interest, which means the more I borrow, the greater profit for you. So you’ll do it for me, yes?”

Holo’s eyes met Lawrence’s as she looked up at him.

They were beautiful eyes with red-brown irises.

“The oil, you mean?”

“Yes. Make it part of my debt, but please — buy it for me, won’t you?”

The plea was strangely rational, and Lawrence couldn’t think of a good rejoinder.

All he could do was slump his head sideways as if exhausted.

“My thanks,” said Holo, brushing against Lawrence’s arm like a cat asking for affection — which wasn’t a bad feeling at all.

He knew that was what Holo wanted, and it was an unavoidable part of his long, lonely time as a traveling merchant.

“Still, you really did haggle him down, didn’t you?” asked Holo, attending once more to her tail as she reclined against Lawrence.

This particular wolf could sense lies, so Lawrence didn’t bother lying and answered truthfully. “Rather he put himself in the position of having no choice but to be haggled down.”

Yet the interest rate on the arms was not good. The most profitable method would be to import the materials and then assemble and sell the weapons. As far as the business of selling completed weapons went, simply by going somewhere with a constant demand for large amounts of weaponry and turning a fair profit, the amount by which the goods could be bargained down was limited.

Lawrence headed to Ruvinheigen for that very same fair profit.

“How much?”

“What’s the point of asking that?”

Holo glanced up at Lawrence from her position leaning against him and then looked quickly away.

At which point Lawrence more or less understood.

Despite her forcing of the oil issue, she was actually quite concerned about his profits.

“What? I was just worried about sponging off a traveling merchant, who is barely scraping by. That is all.”

Lawrence tapped Holo’s head lightly at the nasty comment.

“Weapons are the best-selling product in Ruvinheigen, but many merchants bring them into the city. Thus, the interest rate on them drops, and the amount I could bargain him down is limited.”

“But you bought so much, you’ll yet come out ahead, yes?”

The wagon bed was not full, strictly speaking, but it was well laden. The goods were solid, and though the interest was low, in comparison to Lawrence’s initial investment, the actual amount of material was nice indeed. The fact that he was getting double the material for his investment was icing on the cake. Like the saying goes, “One raindrop raises the sea,” and so Lawrence’s gain might be second only to his profit from the pepper.

In truth, the proceeds would be enough to buy more apples than would fit in the wagon bed, to say nothing of oil, but if Lawrence told Holo that there was no telling what demands she might make — so he held his tongue.

Holo, blissfully ignorant, simply groomed her tail.

Looking at her, Lawrence couldn’t help but feel a bit guilty.

"Well, I should think we’ll make enough to pay for some oil, anyway,” he said.

Holo nodded, apparently satisfied.

“Still, now that I think about it, some spice would be quite tasty,”

Lawrence murmured, as he estimated the likely gain against the cost of the weapons.

“You’ve eaten it?”

“I’m not like you, you glutton. I’m talking about the profit.”

“Hmph. Well, why don’t you load up on spice again, then?” “The prices in Ruvinheigen and Poroson aren’t so very different. I’d take a loss after paying the tariff.”

“Then give it up, I say,” said Holo shortly, nibbling the tip of her tail.

“If I could get a rate about like what I’d normally get for spices or maybe a little more, I’d make enough to open a shop.”

Saving enough money to open his own shop was Lawrence’s dream. Though he’d made a sizable amount in the kerfuffle in Pazzio, the goal remained distant.

“Surely there’s something,” said Holo. “Say...jewels or gold. Those are sure things, no?”

“Ruvinheigen is not a profitable place for such things really.” Perhaps catching a bit of fluff in her nose, Holo gave a small sneeze as she licked her fur. “... Why’s that?” she asked.

“The tariff is too high. It’s protectionism. They levy serious taxes on all but a certain group of merchants. There’s no business to be had there.”

Towns that weakened the foundation of commerce with this kind of protectionism were not uncommon.

But Ruvinheigen’s policy was aimed at turning monopolistic profits. Gold brought to the Church in Ruvinheigen could be stamped with the Church’s holy seal, and such gold would bring safe travels, happiness in the future, or triumph in battle, all by the grace of God. There was even gold for guaranteeing happiness in the afterlife, and it all sold for exorbitant prices.

The Church Council that controlled Ruvinheigen colluded with the merchants under their power to preserve the monopoly, so taxes on gold entering the city were terrifying and punishments for smuggling harsh.

“Huh.”

“If we somehow smuggled gold in, we’d be able to sell it for, oh,

ten times what we paid. But the danger rises with the profit, so I've no choice but to make money bit by bit.”

Lawrence shrugged, thinking wistfully of the end of his road.

In a city like Ruvinheigen, there were plenty of merchants who made in a single day what Lawrence had spent his entire life si riving for.

It seemed unfair — no, worse than unfair, it was downright strange.

“Oh truly?” came Holo’s unexpected reply.

“Do you have some idea otherwise?”

This was Holo the Wisewolf, after all. She might have come up with some unheard-of scheme.

Lawrence turned to her expectantly. Pausing in her grooming for a moment, Holo looked up at him.

“Why don’t you just sneak it in?”

If she was always this foolish it would be charming, thought Lawrence to himself upon hearing her suggestion.

“If that were possible, everyone would do it.”

“Oh, so you can’t do that.”

“When tariffs go up, smuggling does, too — it’s a basic principle. Their inspections are very thorough.”

“Surely a small amount wouldn’t be found.”

“If they do find anything, they’ll cut off your hand at the very least. It’s not worth the risk. It would be worth it if you were bringing a larger amount in ... but that’s impossible.”

Holo smoothed her tail fur and nodded, satisfied with her grooming. Lawrence couldn’t see much difference, but apparently Holo had her standards.

“Mm, ’tis true,” she said. “Well, your business is steady enough. It is well as long as you make steady coin.”

“Right you are, but I seem to have a certain companion bent on wasting that same steady coin.”

Holo yawned, pretending not to hear the gibe as she squirmed to hide her tail. She rubbed her eyes and crept back to her place in the wagon bed.

Lawrence had not been terribly serious. He stopped following Holo’s movements and looked to the road ahead. Trying to talk to her once she decided to sleep was an exercise in futility, so he abandoned the prospect.

For a while he could hear the clattering of weapons as she pushed them aside to make a place to nap, but soon silence returned, and he heard her sigh contentedly.

Lawrence glanced back and saw her curled into a ball, just like a dog or cat. He couldn’t help smiling.

He couldn’t very well say what he thought for many reasons, but he did want her to stay with him.

As Lawrence pondered this, Holo suddenly spoke.

“I forgot to say it earlier, but the wine we got from the master — I’ve no intention of drinking it all myself. This evening we must drink together — and enjoy that mutton, too.”

Mildly surprised, Lawrence turned to look at her, but she was already curled back up.

But this time, she was smiling.

Lawrence looked ahead, holding the reins, and drove the horse carefully, so as not to shake the wagon any more than he had to.

The rolling hills ended, replaced by undulations in the landscape that barely rated the term, which made for easy traveling.

Lawrence hadn’t yet shaken the effects of the previous night’s wine, so the easy road suited him just fine.

With a companion to partake of the fine wine and food, he had overindulged. If he’d had to navigate a mountain trail in his current state, he would likely have tumbled straight to the bottom of the valley.

But here, there wasn’t so much as a river, let alone a valley, so

Lawrence could safely leave the horse to simply follow the road.

Occasionally he would nod off for a brief moment, and in the wagon bed Holo was sound asleep, snoring away without a care in the world. Every time Lawrence started awake, he thanked God for such peaceful times.

After passing many quiet hours this way, Holo finally stirred herself awake just past noon. She rubbed her eyes, her face still clearly bearing the marks of whatever she had slept against.

She hauled herself up to the driver’s seat and gulped some water

from a water-skin, a blank expression on her face. Happily, she did not seem hungover. Had she been, Lawrence might have had

to stop the wagon — otherwise, she might wind up vomiting in the wagon bed, an outcome that didn’t bear thinking about.

“’Tis good weather today,” said Holo.

"It is."

The two exchanged lazy pleasantries, then both yawned hugely.

The road that they were on was one of the major northbound trade routes, so they encountered many other travelers while following it. Among them were merchants flying flags of countries so far away that Lawrence only knew of them from import receipts. Holo saw the flags and seemed to think they were simply advertising the merchant’s home country, but generally the small flags were displayed so that merchants from the same nation could identify a fellow countryman should he pass. Generally such encounters would give way to exchanges of news from the old country. Arriving in a foreign land, where the language, food, and dress were all different, could lead even a constantly traveling merchant to homesickness.

Lawrence explained this to Holo, who then gazed at the small flags of passing merchants, deep in thought.

Holo had left her homeland hundreds of years ago, and her desire to speak to someone from her birthplace was stronger than any traveling merchant’s homesickness.

“Ah, well, I’ll be back soon enough, eh?” she declared with a smile, but there was a touch of loneliness in it.

It seemed to Lawrence that he should have some response to this, but none came to mind, and as he drove the horse along the road, the afternoon sun made the thought hazy in his mind.

There was nothing finer than warm sunlight in the cool season.

But the stillness was soon shattered.

Just as Lawrence and Holo started to doze off in the driver’s seat, Holo spoke abruptly.

"Hey."

“...Mm?”

"T here is a group of people.”

“What’d you say?” Lawrence asked as he scrambled to grab the reins, his sleepiness gone in an instant. He narrowed his eyes and looked ahead into the distance.

Despite the slight undulations in the road, the generally flat terrain offered a good view ahead.

But Lawrence saw nothing. He looked to Holo, who now stood, staring forward intently.

“They are certainly there. I wonder what happened.”

“Are they carrying weapons?”

There were only a few ways to explain a group of people on a

trade road. Lawrence hoped for a large caravan of merchants, a column of pilgrims all visiting the same destination, or a member of the nobility visiting a foreign country.

Hut there were other, less-pleasant possibilities.

They could be bandits, rogues, hungry soldiers returning home, or mercenaries. Encountering returning soldiers or mercenaries might mean giving up everything he owned —if he was lucky.

His life could well be forfeit.

What would happen to his female companion went without saying.

“I ... do not see any weapons. They don’t seem to be annoying ■oldiers, at any rate.”

"You’ve encountered soldiers?” asked Lawrence, slightly surprised.

“They had long, sharp spears, which made them quite a bother.

Though they couldn’t keep up with my wits,” Holo said so proudly that Lawrence didn’t venture to ask what had happened to the unlucky mercenaries.

“There’s...no one about, yes?” Holo looked around quickly, then pulled her hood back, and exposed her wolf ears.

Her pointed ears were the same brown as her tail, and like her tail, they expressed her mood so effectively that they were a good way to tell when she was (for example) lying.

Those same ears pricked forward intently.

Holo’s attitude was every inch the wolf searching out its prey.

Lawrence had encountered such a wolf once before.

It had been a dark, windy night. Lawrence had been following a road across a plain, and by the time he heard the first howl, he was already within the wolves’ territory. Baying sounded from every direction, when he realized he was surrounded, and the horse that pulled his wagon was half-mad with fear.

Just then, Lawrence caught sight of a single wolf.

Its posture was fearless as it had looked straight at Lawrence, its ears so keenly fixed upon him that he was sure it could hear him breathe. He had known that forcing his way free from the wolves’ snare would be impossible, so he immediately took out a leather bag and, making sure the wolf could see, dumped all the meat, bread, and other provisions he had onto the ground. Then he urged his horse onward, the wolf watching him all the while.

He could feel the beast’s gaze on his back for some time, but eventually the howls seemed to cluster around the food he had dropped, and he escaped unscathed.

Lawrence would never forget that wolf. And at this moment, Holo looked just like it.

“Hmm... seems there’s some kind of to-do,” said Holo, bringing Lawrence out of his reverie; he shook his head to clear it.

“Is there a market I’ve forgotten about?” said Lawrence. Road side meetings to exchange information and advance trade were not unheard of.

“I wonder. It doesn’t smell of a fight. That’s for sure.”

Holo pulled her hood back over her head and sat down.

Lawrence was preoccupied with driving the cart as she regarded him with an expression that said, “So what shall we do?”

The merchant was deep in thought as he visualized a map of the area.

Lawrence knew he had to get the arms in his wagon bed to I he Church city of Ruvinheigen. He had signed a contract to that effect with a company in Ruvinheigen. If he detoured now, he would have to backtrack along a very roundabout route — the only other roads were so poor as to be passable only on foot. “You don’t smell any blood, do you?” asked Lawrence.

Holo shook her head decisively.

“Let’s go, then. The detour is a bit too far.”

“And even if they should be mercenaries, you have me,” said Holo, pulling out the leather pouch filled with wheat that hung from her neck. A better bodyguard didn’t exist.

Lawrence smiled trustingly as he drove the horse down the road.

"So, to detour around here, take the path of Saint Lyne?”

“No, it’s surely shorter to take the road that crosses the plains to Mitzheim.”

“Anyway, is that talk about the mercenary band true?”

“Buy this cloth, won’t you? I’ll take salt in exchange.”

“Anyone here speak Parcian? I think this guy’s got a problem!” Lawrence and Holo caught snatches of conversation as they reached the throng of people.

Some of the people stopped in the road were recognizable at a glance as merchants. Others were artisans from different lands on pilgrimages to improve their skills.

Some walked; others traveled by wagon or carriage. Some led donkeys loaded with bundles of straw. Conversation was everywhere, and those who didn’t share a common language gesticulated wildly in efforts to make themselves understood.

Getting into a confrontation because of a language barrier is a terrifyingly unforgettable experience — all the more so when you happen to be carrying your entire fortune with you.

Sadly, Lawrence didn’t understand the man, either. He empathized, but there was nothing he could do, and he didn’t know what the precise problem was anyway.

Lawrence glanced at Holo — a sign that she should stay quietly sitting in the driver’s seat — and hopped out of the wagon, hailing a nearby merchant.

“Excuse me,” he said.

“Hm? Oh, a fellow traveler. Have you just arrived?”

“Yes, from Poroson. But what’s going on here? Surely the local earl hasn’t decided to open a market here.”

“Hah! Nay, were that so, we’d all have mats spread on the ground and be trading the day away. In truth, there’s tell of a mercenary band crossing the road to Ruvinheigen. So we’re all stopped here.”

The merchant wore a turban and loose, baggy pants. The man had a heavy mantle wrapped about his neck and large knapsack slung over his back. Judging by his heavy clothes, the merchant frequented the heart of the northlands.

The dust of the road lingered on his snow-burned face. The many wrinkles and the tanned leather pallor of his skin were proof of a long life as a traveling merchant.

“A mercenary band? I know General Rastuille’s group patrols these parts.”

“No, they were flying crimson flags with a hawk device upon them.”

Lawrence knitted his brow. “The Heinzberg Mercenary Band?”

“Oh ho. I see you’ve traveled the northlands. Indeed, they say it’s the Hawks of Heinzberg — I’d sooner run into bandits than them when carrying a full load of goods.”

It was said that the Hawks of Heinzberg were so hungry for wealth that wherever they passed, not so much as a single turnip leaf would be left behind if they thought it could be sold. They had made their name in the northlands, and if they were on the road ahead, trying to pass it would be suicidal.

The Heinzberg mercenaries were reputed to spot their prey faster than a hawk on the wing. They would be upon a lazily traveling merchant in an instant, surely.

However — mercenaries acted purely out of self-interest, and in that sense, they were not far from merchants. Essentially, when they behaved strangely, there was often something similarly unexpected happening in the marketplace.

For example, a sharp jump or drop in the price of goods.

Being a merchant, Lawrence was naturally pessimistic, but pessimism would get him nowhere, he knew —he was already on the road, loaded with goods. All that mattered now was how he would get to Ruvinheigen.

“So it seems taking a long detour is the only course,” said Lawrence.

“Most probably. Apparently there’s a new road to Ruvinheigen that heads off from the road to Kaslata, but it’s been on the unsafe side lately, I hear.”