THREE

SOUTH SUDAN

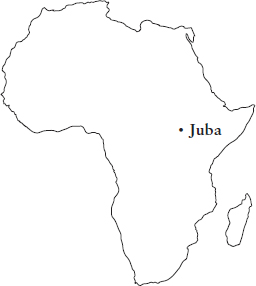

A thousand kilometres from anywhere, among the empty flatlands and bare-rock hills that mark the Sahara’s southern edge, Juba was a place of mud huts and plastic-bag roofs where buzzards lifted lazily on the afternoon heat and children washed in the muddy waters of the White Nile. When I first visited in early 2009, Juba had no landline telephones, no public transport, no power grid, no industry, no agriculture and precious few buildings; hotels, aid compounds and even government ministries were built from prefab cabins and shipping containers cut open at their ends and shoved together like tunnels of tin cans. There were a few businesses, a few hundred policemen, a handful of schools, one run-down hospital and several hundred bureaucrats. With the arrival of thousands of aid workers, there was also the occasional traffic jam of white SUVs on Juba’s five tarred roads and a small clutch of bars filled with hustlers and hookers to soak up those expat salaries. But it hardly seemed to add up to the improbable reality then dawning on the place: barring war, famine or genocide–and all were possible–in less than a year, this sweltering, malarial shanty town would become the world’s newest capital city in the world’s newest country, South Sudan.

How could southern Sudan become an independent nation when it possessed so little of what defined one? Many Juba diplomats doubted it could. They coined a new term to describe its unique status: ‘pre-failed state’. The US was the biggest foreign player in South Sudan, its influence memorialized by a leader, Salva Kiir, rarely seen without the Stetson given him by George W. Bush and a national seal of an eagle over the motto ‘Justice, Liberty, Prosperity’. But the Americans were increasingly downbeat. Former President Jimmy Carter’s Center had worked in southern Sudan for years trying to eradicate guinea worm disease, caught by drinking water containing parasites that eventually burrowed out through the skin. When I asked him whether the south was ready for independence, he replied simply: ‘No’. General Scott Gration, US special envoy to Sudan, described his task as ensuring ‘civil divorce, not civil war’. ‘This place could go down in flames tomorrow,’ he said. ‘The probability of failure is great.’ A US diplomat in the last month of his posting spoke even more freely. ‘Damned if I know,’ he replied when asked how he saw the future. ‘There is an astonishing range of problems that are going to wash over this place.’

Any premature birth presents complications. For South Sudan, they were likely to be particularly severe. As it then was, Sudan was not only the largest country in Africa, it was also one of the least stable on earth. This was the pariah state where Osama bin Laden lived and ran al-Qaeda for five years in the 1990s and on which President Bill Clinton ordered air strikes in retaliation for al-Qaeda’s 1998 bombing of US embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam; where a genocide took place in Darfur a few years later; where the Sudanese President, Omar al-Bashir, was the first head of state to be indicted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes; and where two million people had died in two civil wars between north and south in 1955–72 and 1983–2005. A new country born into that kind of environment that, say, did not have clear frontiers or a functioning government or whose internal tribal division smothered any national spirit would likely spell disaster. And that was just the south. In the north, secession seemed certain to encourage other rebels, such as those in Darfur, or in the east of the country, or in the central-southern states of South Kordofan or the Blue Nile. Jimmy Carter downplayed a comparison many were making to Yugoslavia, where a centralized state splintered in secessionist conflict in the 1990s. Special envoy Gration was less sure. ‘Disintegration is not a foregone conclusion,’ he said.

With failure so likely, why was South Sudan pushing for independence? Why was the world helping it? One answer, as best as I could make out, was George Clooney.

It was a spring morning three years later and the staff were still wiping down the bar and clearing away the empties when Clooney ambled over to my table. He had a couple of hours before he headed north to the fighting and we’d agreed to meet by the Nile at the aid worker hotel where he stayed. The river was something to behold, a wide green trench filled with rain from the plains of Africa, cutting due north across the Sahara all the way to the Mediterranean. But Clooney ignored the view and instead surveyed the empty stools still grouped in convivial circles under the grass-roof bar.

‘You been here at night?’ he asked.

I said I had.

‘So you know it gets pretty wild in here,’ he chuckled. ‘I’ve had some wild nights in here.’

He had just flown into Juba with John Prendergast, his fellow Sudan activist. In a few hours, the pair would be inside a war. To reach it, they would fly to a dirt strip beside a refugee camp in the far north of South Sudan, just below the newly made border with Sudan. There they would transfer to a battered, metal-floored SUV driven by Ryan Boyette.

Ryan was an American and a former aid worker who had married locally and never left. He had volunteered to drive Clooney and Prendergast illegally across the border and into the Nuba Mountains. The area was rebel territory. Ryan and his wife lived there in a stone house they built themselves, which had become Ryan’s base for his project documenting atrocities by the Sudanese regime. A few months earlier, the Sudanese air force had dropped a bomb 100 metres from the house. The trio’s route would take them up a dusty track that the planes were hitting almost daily. It was the bombings–barrels of oil attached to explosives rolled out of planes more than a mile up–that Clooney had come to see. ‘It should be interesting,’ he said. ‘They’re dropping those bombs from 6,000 feet so their effectiveness has been mostly to terrorize and less to actually… The bigger issue is violence on the road. Some guys just shot and killed and slit the throats of some people going up that road. So you have to be careful.’

I asked him if he was worried. He shook his head. ‘It’s OK,’ he said. ‘We’ve been in some sticky situations before and we’re going with some guys who know what they’re doing. And you know, you gotta do it.’

If we had to have celebrities, it seemed to me George Clooney was absolutely the best kind. It was nine months after South Sudan’s independence and he was on his seventh trip there in as many years. In that time his activism had cost him hundreds of thousands of dollars. I could only imagine the angry conversations he must have endured with worried studio heads and Hollywood agents when he announced he was off to war in Africa. Now one of the biggest stars of his generation was about to fly to a spot about as far from a hospital as it was possible to be on earth, then drive up a dirt road in the hope of getting bombed.

By crossing the border, Clooney would be passing from Africa into Arabia. When it was one country, Sudan had straddled that line. In centuries past, like European Christians, Arabs had chosen to enlighten heathen Africans through slave-raiding, then conquest, then economic marginalization. After independence in 1956, the Arab-dominated Sudanese regime took its cue from this history, creating an autocratic state that exploited its regions for oil, then spent the money on itself in the capital. It was precisely that kind of behaviour that provoked the tide of African liberation in imperial times. So it was that Khartoum was soon confronting rebellion in almost every region, especially in its more Christian and African south.

Khartoum responded with repression and, after a military takeover in 1989, the kind of strident Islam that persuaded bin Laden to make Khartoum his home. Partly because of the sheer number of dead in Sudan’s many conflicts, partly because Islamists became America’s Enemy No. 1 after 9/11, partly because Sudan’s continued use of slaves horrified a nation whose own creation myth was so bound up in the trade, Sudan became a central cause for young American activists in the first years of the new millennium. And George Clooney, one of their favourite movie stars, became their champion.

Clooney’s campaigning had evolved with the progression of Sudan’s various rebellions. Initially he spoke out against the Sudanese regime’s atrocities in Darfur. After the US government designated that conflict a genocide in 2004, Clooney was among those who successfully campaigned to have the International Criminal Court indict President al-Bashir. In 2005, the US brokered a peace agreement between Sudan and its southern rebels, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). The deal included a referendum on secession and in the years that followed, Clooney’s advocacy, which included interviews, television appearances, addresses to Congress, the Senate and the UN Security Council and talks with President Barack Obama, helped convince the world the south should be allowed independence. He was duly on hand in Juba in January 2011 when southern Sudanese voted by 98.8 per cent to split from the north. ‘It was wild,’ he said. ‘I literally watched this 90-year-old woman vote for the first time in her life for freedom. There’s something mind-blowing to see 98 per cent of the people voting. They consider it a duty and an honour and a privilege.’

Despite the peace deal, Khartoum never wavered from its preference for killing its opponents. Those included southerners, but also other rebels such as the Nuba who remained within its new truncated borders. Clooney was on an earlier trip with John Prendergast trying to figure out ways to hinder the bloodshed when, lying out in the desert and looking up at the stars, the pair came up with an idea even more outlandish than helping create a new country in Africa: their own spy satellite. ‘I was like: “How come you could Google Earth my house and you can’t Google Earth where war crimes are being committed?”’ said Clooney. ‘“It doesn’t make sense to me.” And John was, like, “I don’t know. Maybe we can.”’

On their return to the US, he and Prendergast contacted Google Maps and a satellite photography specialist, DigitalGlobe. They rented time on three of DigitalGlobe’s satellites stationed in the stratosphere over Sudan and worked to process the images and overlay them with Google Maps in minutes. Speed was important, said Clooney. ‘Then you can say, “Well, five days ago this is what this place looked like. And this is what it looked like two days ago.”’

I told him I thought the idea was brilliant, if a little insane. The point, he said, was that it worked. ‘If you’re going to put 150,000 troops on a border, you’re going to have a really tough time claiming this is all just rebel infighting if that’s all going to be photographed by satellites, up close and personal. It makes it harder to get away with. It makes it impossible for the UN Security Council to veto action against Khartoum. We know it’s effective because the government in Khartoum keeps saying what a rotten bunch of people we are and how it’s not fair.’ He laughed. ‘I love the “It’s not fair” thing,’ he said. ‘Literally stomping their feet. “It’s not fair!” The Defence Minister came out and said: “How would Mister Clooney like it if every time he left his house there were people watching him with cameras?” And I was, like, “Man, I want you to enjoy the exact same amount of celebrity as me.”’ He laughed again. ‘You can’t please all the war criminals all the time, you know?’

You had to admire the inversion. George Clooney, whose privacy was routinely invaded in pursuit of trivialities, was violating the privacy of a dictatorial regime in the pursuit of saving lives. He was using his fame and fortune to try to effect positive change in a place that, without him, would have remained far more obscure. He presented a far less self-indulgent model of celebrity than usual and, with the way his stature in his industry seemed to persuade other stars to take up activism in Africa, could even lay claim to helping reinvent the whole notion and purpose of fame.

Clooney also knew his limits. He had a clear goal–prevention of human suffering–and a well-defined idea of his role. ‘The reason I come is not because I’m a policy guy and not because I’m a soldier and not because I can do anything except get this on TV and in the newspapers,’ he said. Nevertheless, publicity was key. ‘The thing that’s frustrating and disappointing–and you in the news organizations know this better than anybody–is that the assumption is always: “Well, if we know, then we do something about it.” And that just isn’t true. I mean we knew about Rwanda. We knew about Bosnia. We knew. But there was plausible deniability. So we’re going to try and keep it loud enough so that at least they can’t say they didn’t know.’

George Clooney’s efforts revealed imagination and depth. His campaigning was also effective. But in some ways, that only made it stranger. Because he was charming and handsome and famous and rich, he had been able to help engineer the creation of a vast new country in a faraway land. The fabulousness of one of Hollywood’s leading men, normally used to sell movie tickets and watches and coffee, had changed millions of lives and the course of history. Good for him. But if this was how Western power operated in the twenty-first century, it was absurd.

At one point I asked Clooney if he’d ever met his northern Sudanese adversaries, whose consistent complaint was that Sudan’s future wasn’t the business of an American actor, no matter how cool he was. He replied that his one trip to Khartoum had been frustrating because the government obstinately refused to listen to him. As Clooney saw it, they forced him to play tough. ‘We’ve tried carrots,’ he said. ‘I’ve been the first to talk about seeing if there’s some door to open to allow these guys to step through and have an easier way of it. But carrots haven’t been very successful with the government of Khartoum. They don’t want to do it. So now we have to make it much harder.’

Clooney was not asking himself, as I was trying to, what any of this–Sudan–had to do with him. Rather, he was acknowledging that in practice it had had a lot to do with him, from the moment he decided it would. He had the clarity of moral obligation. Because he could, he should.

I felt his certainty was blinding him to something. With his campaigns, Clooney was acting on behalf of others. Inevitably, like when he rented a satellite, that sometimes meant instead of them. When I asked him about his role in making a new country, what I meant was: why should a Hollywood star wield such influence over a distant foreign land? Why should any outsider? How, really, could you foster someone else’s independence? Surely the whole point with independence was that people had to do it for themselves?

Twenty-one months later, South Sudan imploded.

On 15 December 2013 there was an attempted coup in Juba by ethnic Nuer soldiers from the presidential guard. Or, as the Nuer had it, Dinka soldiers acting on orders from a paranoid Dinka President, Salva Kiir, tried to disarm them by force. A firefight erupted in the barracks and spilled out onto the streets. Around 500 soldiers died.

The violence reflected an unresolved split among South Sudan’s leaders. All through their fight with Khartoum, the southern rebellion had been riven by ethnic rivalry, particularly between the Dinka, the biggest tribe, and the Nuer, the second-largest. During the civil war, more southerners had died fighting each other than the north. At times the Nuer leader, Riek Machar, even sided with Khartoum. In a notorious attack in 1991, he had sacked the Dinka capital, Bor, massacring thousands of civilians.

At independence in July 2011, the Dinka took most government and army posts. Kiir made an effort to broaden the government’s base by making Machar his deputy. But relations between the two never healed. In July 2013 Kiir fired Machar, along with his entire Cabinet, replacing them with Dinka loyalists. After that, another showdown was only a matter of time. The soldiers’ firefight provided the spark. Within hours of that first clash, Dinka soldiers began carrying out pogroms across Juba, singling out Nuer soldiers and civilians and shooting them in their homes and in the street. Nuer mutinies erupted in army units across the country. Machar fled the capital and set up a command post in the northern bush. Nuer militias soon began their own series of reprisal massacres against Dinka.

In days, the conflict was threatening to widen into a regional war. Machar was receiving tacit support from Ethiopia and at times seemed to be angling to restart the north-south war, making overtures to Khartoum about renegotiating the split the south paid it from its oil revenues. Kiir, meanwhile, welcomed reinforcements of several thousand Ugandan soldiers. Inside South Sudan, the conflict was tearing apart the new country’s fragile national fabric. Nuer and Dinka mobs began attacking their neighbours. Militias went from house to house, demanding to know who was Nuer, who Dinka. Thousands were executed, their bodies left in the street. Children were shot as they ran. Fathers had their throats cut in front of their families. Women and girls were abducted and raped.

Coming on the twentieth anniversary of the Rwanda genocide, the bloodletting sharpened memories of how, a few hundred kilometres to the south, up to a million people had died in 100 days. With each new massacre, the parallels grew. Like Rwanda, families turned on each other. Like Rwanda, women and children who sought safety in churches and hospitals and schools and outside UN bases were slaughtered en masse. When a Nuer militia fell on the town of Bentiu, massacring hundreds on 15 and 16 April, the UN reported that the killers were spurred on by broadcasts on local radio stations, just as they had been in Rwanda. And like Rwanda, the UN failed to stop the slaughter even when it happened right in front of them. The day after the Bentiu massacre, Dinka militiamen stormed a UN base at Bor and started shooting and slashing at Nuer refugees inside the perimeter, killing at least 58.

Twenty years before, the world had promised never again. Now newspapers around the world asked: were those empty words? Was it happening again? How could it be, when for a decade South Sudan’s very creation had been a project nurtured and guided by the world’s best intentions?

By the time I arrived back in Juba in mid April 2014, the violence had been raging for four months. Three provincial capitals had been razed. Up to 40,000 people were dead. More than a million of South Sudan’s six to 11 million people (a measure of South Sudan’s lack of development was that nobody knew the population for sure) had fled their homes and 250,000 of those had walked abroad. With no one left to tend the farms, the UN was warning that seven million South Sudanese needed food aid and 50,000 children could die of hunger in months.

George Clooney was now pointing his satellite at his former friends in the south, particularly the city of Malakal, a state capital, an hour’s flight north of Juba. Nuer rebels had overrun Malakal three times. Three times the SPLA had recaptured it. The last period of rebel occupation in February had been especially devastating. Clooney’s before-and-after pictures showed that where once there had been hundreds of tin shacks and thatched huts, now there were just blackened smudges. More fighting around Malakal seemed imminent. South Sudan’s government depended on nearby oilfields for 98 per cent of its revenue. For his part, Machar was vowing to take those, then Juba, then overthrow Kiir.

Mading Ngor, a South Sudanese journalist with whom I worked, fixed us a ride to Malakal in the cargo hold of a government military resupply flight, a cavernous white Ilyushin packed with food and ammunition flown by seven portly Ukrainians. We sat on the back of a camouflaged, flat-back Land Cruiser, wobbling on the truck’s suspension as the plane hit turbulence thrown up by the 45-degree heat below. Before we left, Mading and I had sought out a South Sudanese official who had just returned from Malakal. ‘You will find mostly bones,’ he said. ‘They killed them in the streets and in the churches and in the hospital, then they burned the town to the ground. The dogs and the birds have been at the bones. Malakal isn’t there any more.’ Sure enough, when the Ukrainians threw open the Ilyushin’s door at Malakal, I immediately smelled the bilious stench of bloating corpses.

We walked to the side of the runway. Around 200 people were gathered on its edge, apparently surrounded by everything they’d managed to save. Bedsteads. Bicycle wheels. Tightly packed suitcases. Whole sheets tied up in great bundles. They told us they’d been there for weeks, hoping for a ride to Juba. The Ukrainians unloaded the trucks, pulled up the crew ladder and made ready to depart. Suddenly there was a cry and as one the crowd picked up their cases and mattresses and babies and ran to the open plane door. A stand-off ensued. The crowd remonstrated from the tarmac. The Ukrainians refused to lower the ladder. A dog began circling the nose wheel, barking at the pilots above. We left them to it.

With Malakal destroyed, we were staying at a UN base around a kilometre outside town. The road there was lined by hundreds of rope beds, set out like an endless open-air dormitory. Underneath were small piles of plastic bags, tin plates, car wheels and bamboo poles. People were busily adding to their piles, arriving from Malakal carrying wooden planks, plastic sheets, plastic chairs, more poles and more beds. Marabou storks as tall as teenagers strutted between the beds, stooping and picking.

We passed two SPLA technicals mounted with .50 cals and suddenly we were in a small market. Tiny mountains of tomatoes, onions, nuts and tamarind were stacked on the bare earth under sheets of plastic tied between poles. A hundred metres further on and we were at the gates of the UN base. We drove through to the other side to find more market stalls and thousands more people. At first I thought the UN had opened its gates to the refugees. But after another 50 metres we passed through a second set of gates, these ones ringed with razor wire and policed by a sentry checking IDs, and the people and the noise ended.

We were in a large yard packed with perhaps 100 giant white machines. Bulldozers, heavy-loader trucks, water-carriers, buses, a rubbish truck, a crane, a tank, an immense red fire truck and, beside it, 32 50-litre fire extinguishers still wrapped in cellophane. We turned into an avenue of prefabricated bungalows, perhaps 100 long and five rows deep on each side, around 1,000 cabins in all. Parked in front were hundreds of white SUVs marked ‘UN’ or stamped with the logos of international aid agencies: Médecins Sans Frontières, Solidarités, the Red Cross, the International Organization for Migration. A square air-conditioning unit stuck out from each bungalow. Most had a satellite dish on a metal spike out front. Some were surrounded by small gardens of aloe, neem and pink and white bougainvillea. Wooden boardwalks ran between the bungalows, flanked by concrete drainage ditches marked with red and white painted bollards. Every now and then the walkways would open up to small parks, in the corners of which were white rubbish bins and shelters protecting more fire extinguishers. Towering over the whole complex were several red and white radio masts and sodium street lights.

We wandered down the main street. Aside from a passing jogger dressed in Lycra with an iPod strapped to his forearm, the base looked deserted. We came across a cafeteria. Then came a bigger building on whose arch was written, ‘Hard Rock Complex’ in the style of the US chain. We passed a white UN pick-up with a dirt bike in the back. After that came a residential area, hundreds of cabins served by several shower blocks plumbed with hot and cold water and fitted with condom machines. Many of the buildings displayed UN posters. ‘No to abuse in the workplace’, said one over a photograph of a suited man in an office shouting at a woman through a megaphone. ‘Sex with children is prohibited’, read another.

Looking for someone to ask where to pitch our tents, Mading and I tried knocking on a few doors. We opened one to find three Ukrainians in air-conditioned cool looking up at us from computer screens. I asked if they knew where the base manager was. They looked at me blankly. ‘This internet café,’ said one. After a while we found a door marked ‘Administration’. Inside a man sat at his desk, typing on his computer. He was bald and dressed in sandals, denim shorts and a freshly ironed short-sleeved shirt coloured in pastel checks. A badge around his neck announced that he was Imad Qatouni, UN general services assistant. ‘No, no, no, we do not have any accommodation,’ remonstrated Imad as we walked in.

I asked how things were. ‘So far, so good,’ replied Imad. I tried again, asking how many refugees there were. ‘Maybe 22,000,’ said Imad. ‘They come and go. It changes every day.’ Imad told us he would find someone to show us where to put our tents. Then he said: ‘We are providing catering for everybody.’ For a moment I thought he meant the refugees. He didn’t. ‘It’s 20 South Sudanese pounds for breakfast, and 30 for lunch and dinner. Very reasonable. Out there even a tomato will cost you 15 Sudanese pounds. We even reduced the prices. Tonight you will get turkey, spaghetti, rice and soup.’ Imad smiled. ‘I am running this,’ he said, opening his palms and indicating a pile of papers on his desk. ‘Look at me. It’s the weekend and all I am doing is going through the receipts. Thousands of them.’

I took in Imad’s office. Shelves stacked with files. A kettle and coffee mugs. A water cooler, a fridge, a printer and a separate photocopier, piles of spare printer paper and toner cartridges. On his desk next to his keyboard: a box of paperclips, sealed stacks of yellow and pink Post-It notes, a can of air freshener and a small bottle of hand sanitizer.

I asked about going into Malakal. ‘There is no town,’ said Imad. I said we’d heard as much. It was the destruction we had come to see. Imad said he couldn’t help us. ‘I have never been outside,’ said Imad. ‘I have nothing to do there. The military have to do it, so they do patrols. Some of the NGOs go with them. Maybe you could go on patrol too.’

The next morning Mading phoned a friend in South Sudan’s military and a jeep came to meet us. On the way into Malakal we passed hundreds more people carrying more piles of belongings on their heads. At first, the destruction of the city announced itself quietly. A smashed doorway on the outskirts. A burned-out hut. A small stall spilling plastic and paper into the street. Then suddenly Malakal ceased to exist. In every direction was black earth, blackened stubs of walls and bent tin sheets. It was as though a hurricane of fire had passed through.

Mading and I got out. We began walking through the debris, sinking up to our ankles in the ash. A blackened fan. A blackened cooking pot. A rocking chair burned back to its metal frame. Cracked beer bottles. A small pile of melted medicine bottles. The warped back of a mobile phone. I came to a metal front gate, now standing alone, the walls on either side vaporized. Behind it was what had once been a front yard and a small flower bed, its borders marked with half-buried cans of Red Horse and Heineken. Beyond that a brick house still stood, though its windows were blown out and the walls around them were smudged with sooty eyeshadow. I peered inside. There were two small rooms. In each were three metal bed frames. There was a clothes dryer, a gas bottle, a hat stand with curled hooks, a shisha pipe, a spilled sack of rice, a pair of green flip-flops and a neatly stacked pile of tin plates and cups. Everything except the flip-flops was blackened and cracked, twisted or blistered. We were walking through incinerated lives.

Sleepless the night before, I’d ambled around the UN base and found scores of dogs lying in the road. Mindful of what the man in Juba had said about dogs and corpses, I’d watched one pack rummage through a garbage pile, tearing and growling and settling down to chew. Now I rounded a corner and saw more dogs. They tensed, snarled and bounded guiltily away. They looked well fed.

We climbed back into our truck and drove 100 metres before Mading said ‘Oh!’ and motioned for the driver to stop. We began walking again, stepping over a pile of mobile phone covers, then TV remotes, then around a large safe, its door wrenched open. I saw what Mading had seen: we were in the main market. Every store lock had been smashed, every metal door wrenched and everything inside looted. The signs, twisted and burned, took on a new, bitter tone. ‘Tourist Restaurant 5 Stars’, read one. ‘South Supreme Airlines: the Spirit of a New Nation’, read another. To one side was an old aid agency sign. ‘Multi-donor trust fund for South Sudan’, it said. ‘Rapid Impact Emergency Project 2008: Rehabilitation of Market’.

The wreckage under our feet began to assume a medical theme–pill bottles, medicine sachets–and I looked up and saw a sign indicating we were outside Malakal Teaching Hospital. We walked through the front gates over a carpet of silver condom strips. Computers had been dragged out of the hospital’s offices and smashed. Patient records littered the corridors. Outside the children’s ward were hundreds of large paper sheets printed with the board game Ludo. Gold and purple Christmas tinsel hung on the walls. As we approached the operating theatre, a growling announced the hidden presence of another dog pack. On the walls outside were aid agency posters. ‘Take an HIV test’, advised Unicef. ‘Fight for rights’, said the UN. Next to them someone had written their name in blood: ‘Bishok’. It was the last testimony to an existence presumably now erased. And maybe an accusation, too. What use, in the end, had health or rights programmes been to Bishok?

We drove to Malakal’s river port. I’d read how in early January more than two hundred people trying to escape the violence had drowned crossing the Nile when an overcrowded ferry sank. Most of the dead were children. Now I saw some had not even made it that far. Just by the port gates a small skull lay next to a tiny shinbone. Inside there were more bones. An arm, a leg, another small skull next to a black silk hairband. As I walked over, I kicked something. A tiny coccyx skittered across the concrete.

Bar the dogs, we had seen no sign of life. But as we left the port and rounded a corner, we found a group of government troops encamped by the side of the road. We stopped to talk to some officers. ‘Go to the church,’ said one. ‘You can get all you want.’ A hundred metres further on and we were outside St Joseph’s Cathedral. We walked through the front gates, across more piles of papers and garbage and up the front steps, stepping over a dark patch of blood. At first I couldn’t understand what the soldier had meant. There were no bones here. Instead the floor of the cathedral was a sea of brightly coloured clothes, mixed in with a few plastic bowls and cups.

But there was something about the way the clothes were arranged. Small, neat piles. Perhaps 250 of them. We began stepping through the mess, picking up the clothes. Dresses. Skirts. Blouses. They smelled of washing powder and perfume. Tucked underneath were several collections of family photographs. A picture of a man relaxing on a picnic in a grassy field. Another of a woman with two girls, her daughters perhaps. A picture of a woman with triplets. A graduation portrait. Another of five children, aged about one to 10. These were the kinds of photographs mothers kept. They would have grabbed them as they fled their homes. Where were the women now? What had happened here to make them abandon their keepsakes?

We drove back to the camp outside the UN base and began asking around among the refugees. A rainstorm had broken and most were huddling under plastic sheets, tucking themselves up on their rope beds to keep out of the mud. Ernest Uruar was 52, spoke some English and wore a turquoise Unicef cap. ‘I was in the hospital after Christmas,’ he said. ‘We ran there to save ourselves. My two boys, 16 and 14, died trying to get away when a canoe sank in the river on Christmas Day. So it was just me, my wife and my mother-in-law.

‘We were there when the rebels came the third time. They were just killing people, even the wounded, even my mother-in-law. People ran and they opened fire. They were asking, “Who is Dinka? Who is Nuer?” If you were Dinka, you were shot. It didn’t matter even if they were children. It was only being Dinka that mattered.’

Ernest was neither Dinka nor Nuer. He’d run with his wife to the cathedral. Hundreds of others did the same. ‘The rebels were looting the town,’ he said. ‘Then they were coming to the cathedral to look for girls. They raped them. They would take girls in front of their mothers and fathers. Some were returned, some were not.’

I asked how long this went on for. ‘Two months,’ replied Ernest.

I looked at Ernest. ‘Two months? The rebels used the cathedral as a rape camp for two months when there was a UN base full of peacekeepers ten minutes away?’

‘Two months,’ repeated Ernest.

A woman introduced herself as Asham Nyiyom. She said she was 50 and the mother of eight. ‘The rebels came constantly to the cathedral,’ she said. ‘They were asking for money and taking young girls. They selected some people to be killed. They even shot one man dead in the church. My 18-year-old son is also missing.’ A younger man who’d been listening interrupted. ‘They would say: “You come, and you, and you,”’ he said. ‘They would take these girls and use them. One night they took seven and they did not return two. We don’t know what happened to them. My sister was killed. And other relatives.’

The man caught his breath. He was trembling.

‘Only I came out,’ he said. Abruptly he walked off.

Ernest watched him go. ‘It was a very bad situation,’ he said. ‘Even you cannot describe on this. How it became. How we became. They would kill people when they went to the river to fetch water.’ The rapists did not spare mothers with babies, said Ernest. ‘When they take the girls, if you are a man and you want to say something, they will beat you and kill you. It was two months of killings and abuses and rapes. And then the UN came. After the rebels had left. They did not risk until it became peaceful. They saw people dying and they did not move. They did not move until the government recaptured the place.’

I asked Ernest what he thought of the protection offered by the UN. He considered his reply. ‘In a way, they had a hand in all this,’ he said, eventually. ‘They saved our lives late.’

Lunch back at the base was rice, lamb, broccoli and black-eyed peas. With most base residents cocooned all day in their air-conditioned cabins in front of their screens, mealtimes were some of the few occasions we got to see them. They would emerge in Bermuda shorts, T-shirts and sandals, shuffling to and from the cafeteria, perhaps stopping in at the Hard Rock Complex to use the gym or shoot some pool in the rec room.

I struck up a conversation with a Fijian policeman who was living in the bungalow next to my tent. He let me use his cabin to charge my computer, a gesture, he explained, of ethnic solidarity. I was British and Fiji had been a British colony. That made us allies.

After a while, I asked: ‘Against whom?’

‘Not all the UN people are friendly,’ replied the Fijian. ‘They lock the toilets and showers. They think they should be only for them.’

That morning an Indian soldier had reprimanded me for using his shower block. I told the Fijian. He erupted. ‘This fucking guy and his fucking toilets,’ he said. ‘He write three times to the camp commander about this. He put his own locks. We go out at night and take his locks and throw them away.’ The Fijian stewed for a moment, breathing heavily, rocking back and forth. ‘These are not good people,’ he said.

The uniform on the Indian from the shower block indicated he was a peacekeeper. I’d noticed he and many of his comrades wore surgical facemasks and asked the Fijian why. ‘They say it is because Africans smell, because Africans are dirty,’ he replied. ‘This is not good. You see how these people are living. We are here to protect them. You should not wear a mask. Me, I talk to them. They offer their food and I eat it. I sit with them. These fucking UN people, they never eat Sudanese food. They never meet the people. They are not good with them.’

In the afternoon, Mading and I went to meet the SPLA general who had retaken Malakal from the rebels for the third time, Johnson Bilieu. En route, we passed hundreds of soldiers carrying furniture out of deserted houses and loading up trucks in the street. We mentioned it to the general but he was defensive, denying he had looters in his ranks. We let it pass.

The general said thousands had died. He apologized for not being more precise. Hundreds of bodies had been washed away by the river, he said. The dogs had dragged away those that remained. They split up the skeletons so it was impossible to make a proper count. I asked the general what he made of the UN’s efforts to protect civilians. ‘Slow,’ he said.

Mading and the general began a long discussion about tactics and it was late afternoon by the time we left. Driving back to the base, we took a different route through town. I was thinking about the bodies. The general had said there were thousands but I’d only seen a few bones. The dogs couldn’t have taken them all.

We passed an open field with a number of earthen mounds in it. It took me a few seconds to register what I had seen and I had to ask the driver to turn around and go back. The field turned out to be the town cemetery. Just inside the gate was a large expanse of freshly dug earth, perhaps 25 metres wide and broad. Behind it was another one, and behind that, and further on, and on either side, several more. I made a tour of the cemetery and counted 13 large mounds, 24 medium-sized ones and more than a hundred small ones. There was the same stink as at the airport. Sitting on one mound was a skull, half of its cranium missing. I asked our government driver if he knew how many people were buried in each large grave. ‘About 20 to 30,’ he replied.

Mading phoned General Bilieu. The graves weren’t dug by his men, he said. But by then we already knew. In the earth were the tracks of fat-tyred heavy-lifting machines of the kind sitting at the entrance of the UN base.

The world had guided the South Sudanese to freedom. Two and a half years later, it was shovelling their bodies into mass graves with bulldozers.

The first modern celebrity activist was a child actor called Jackie Coogan, once a co-star to Charlie Chaplin. In 1924, aged 10, Coogan raised a million dollars for Armenian and Greek refugees left destitute by World War I. Coogan died in 1984. If you visit his grave in the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California, you might think you were standing before the tomb of a politician or civil rights leader. ‘Humanitarian. Patriot. Entertainer’, reads the stone. The last word is the only reference to the role for which millions knew Coogan: Uncle Fester in the 1960s comedy The Addams Family.

The accusation most commonly levelled at celebrities with a cause is that too often it is more about the saviours than the saved. This suspicion of self-interest is not new. In the late nineteenth century, the first attempt by outsiders to improve health in Africa was not even aimed at Africans but at European settlers, who were dying in droves in the continent’s interior. It was Africa’s particular misfortune that Europeans learned to beat many of the continent’s diseases in the 1880s and 1890s just as their colonial ambitions peaked. Cures and treatments followed in quick succession, including those for yellow fever in 1881, tuberculosis in 1882, cholera in 1885 and malaria in 1898. If the Berlin conference gave Europe a plan for conquest, advances in tropical medicine–a bed-net to prevent malaria, salt, sugar and water to treat cholera–expedited them. In a few years, the Belgians had built rubber plantations across Congo, the Portuguese were growing coffee and sisal in Mozambique and Angola, the Germans were breeding cattle in Namibia and Tanzania, the French were farming groundnuts from Dakar to Niamey and Britons were planting wheat and fruit farms across Zimbabwe and Zambia, Ghana and Kenya.

Most of these farms formalized racist oppression. The white boss lived as a feudal lord in a palatial villa at the centre of his vast lands, ruling over hundreds of African men, women and children in the fields whom he kept in line with rhino-skin whips. If Africans benefited from their bosses’ new mastery of disease, it was as an afterthought when the colonists, either out of conscience or a calculation that a healthy negro was a more productive one, let their workers have spare medicine and old bed-nets.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the dying years of colonialism, the newly formed United Nations created two departments, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef), and charged them with improving the health of the world’s poor. But this lofty, universalist-sounding mission was also born of a pronounced Western bias. The term ‘United Nations’ was a front, invented by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to give a veneer of internationalism to a pact of martial division: the 1942 Declaration by the United Nations, which committed all 26 Allies to global war until the Axis powers were defeated. As the Cold War took hold, the UN remained largely a Western political tool, dependent on American and European government funds and approval. Soon the US and Europe came to regard the UN’s health agencies as an excellent way to convince the poor world that the capitalist West cared more for them than the Communist East. By the late 1950s, they were funding the new agencies plus their own government efforts with hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

The results were spectacular. In a decade, malaria, the most deadly disease ever to afflict mankind, declined from 350 million cases a year worldwide to 100 million. Eighteen countries became malaria-free. By the late 1960s, however, many of the UN’s early successes were being reversed. The UN’s malaria programmes withered and died as a new environmentalist movement questioned the toxic impact of the mosquito-killer dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). All the health campaigns also foundered on the realization that, once a disease was beaten back, it would take all but everlasting campaigns to keep it at bay. Perhaps most significant, the way the West had used aid to buy Cold War allies rankled the activists and idealists of the late 1960s who might have been expected to most approve of it. New non-government groups sprang up, proclaiming they were focused on people, not power, and declared their intention to be independent, politically neutral and benevolent to all. They gave themselves a name to capture this universal righteousness: humanitarians.

One day I made a request under Britain’s Freedom of Information Act asking the Foreign Office to release secret files dating from 1967–8 on the Biafra civil war in Nigeria. The country’s northern elite had been favoured by its British imperial rulers and had continued to dominate the country after independence in 1960. But in 1967 southern ethnic Igbos rebelled, declaring the secession of a new state they called Biafra.

If I had been looking for state secrets or tales of James Bond adventures in the British files, I would have been disappointed. British spies of the 1960s, it seemed, mostly extracted their intelligence by reading newspapers and taking reporters out to lunch. But as I’d suspected, much of the Biafran file was taken up with reports on a pioneering Geneva-based PR agency, Markpress, run by an American, William Bernhardt, who in a few short months laid the foundations of modern humanitarianism.

The Biafran rebels had hired Markpress to generate support in the West. MI6’s file provided a methodical account of how, by co-opting celebrities and journalists, the agency created the first modern aid campaign. In a letter marked ‘Confidential’ dated 16 October 1968 and addressed to London from the Swiss town of Berne, a British operative who signed himself P. Arengo-Jones wrote: ‘[Markpress] has for over a year, we hear, been flying out groups of German and Swiss journalists. It has a member of the Associated Press office in Geneva working for it. I fear there is not much in this, if anything, which will be new to you but you may nevertheless like to have a sight of it.’

Despite his insouciance, P. Arengo-Jones was persuaded to persevere with his investigations. Over the months, his letters revealed a growing astonishment at how Markpress was able to generate unprecedented public interest in Biafra by presenting the need to get involved in the affairs of a far-off land as motivated less by political creed or national or commercial self-interest but by a higher human purpose. What so mystified Arengo-Jones was how, despite relying on journalists working on a commercial basis and being profitably contracted itself, Markpress was able to convince the public of the campaign’s selfless, elevated ethics–of its own good intentions and of the public’s need to act, the need to do something. ‘We are finding it very difficult to isolate the mercenary involvement of people with Markpress from their humanitarian concern for the Ibos [sic],’ wrote Arengo-Jones. ‘One of them we know to be working with Markpress, a well-known broadcaster, makes frequent trips to rebel-held parts of Nigeria but is always able on his return to broadcast about what he claims to have witnessed as a radio man.’

The central aim of Markpress’ campaign was to persuade the outside world of the need for a new type of Western intervention. This was not to be about killing others or seizing territory or protecting interests. It was to save lives, restore some morality to the exercise of rich-world power and rid it of the notoriety it had garnered propping up Cold War despots around the world. (Nigeria was a case in point. The British government was selling arms to the government.)

Though the campaigners would have been loath to admit it, their appeal to a higher calling drew on colonial precedent. Imperialists believed the exercise of European power necessarily improved a place. The Biafran humanitarians believed it would too, if wielded by the right people for the right reasons. The bad guys in Markpress’ Biafran presentations would also have been familiar to any God-fearing colonist. They were Muslim, in particular soldiers of the Muslim-dominated Nigerian army and the Muslim mobs who beat and killed Christian Igbos. The campaigners described the crimes of these Islamist barbarians with a word which in later years would become a holy grail for those advocating humanitarian intervention around the world: genocide.

The most striking of Markpress’ innovations was its creation of a campaign icon that would also echo through the decades: the starving African baby, on whose behalf action was required. But once again the agency drew on colonialism when it cast foreign campaigners as the hero-saviours in this African story. As it had been with missionaries and imperialists, the idea was to give the public a personal incentive to adopt what was otherwise a distant and obscure cause. By backing the campaign, you became one of the good guys. Who could dispute the bravery of the aid workers flying food into Biafra, 29 of whom were killed by the Nigerian air force and their Soviet allies? Who could doubt the sacrifice of American student Bruce Mayrock, who died on the lawn in front of the UN building in New York after setting himself alight carrying a sign that read ‘You Must Stop Genocide’? Who could resist the chutzpah of John Lennon, who returned his MBE on 25 November 1969, explaining in an accompanying letter to Queen Elizabeth II: ‘Your Majesty, I am returning my MBE as a protest against Britain’s involvement in the Nigeria-Biafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam and against “Cold Turkey” slipping down the charts. With Love, John Lennon.’

A million people died in the Biafran conflict, hardly a humanitarian success. It’s a testament to both the tenacity and the introspective spirit in which humanitarianism was forged that Biafra remains a template today for the ideas, organizations and individuals it brought to prominence. Biafra saw the arrival of two concepts: the charity helper working under commercial contract; and the permanent charity built around a never-ending global mission to address crisis and do good that reserves for the charity the prerogative of deciding what, and where, is a crisis, and how good should be done. These concepts remain prototypes for the modern aid worker and aid group. Biafra echoes especially loudly in a certain type of swashbuckling aid worker who first emerged there. Unicef, Save the Children and Caritas were all on their first foreign ground operation in Biafra, and Oxfam only its second. Médecins Sans Frontières, the most glamorous of all aid agencies and the winner of the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, was founded specifically for Biafra by Bernard Kouchner, the future French Foreign Minister. Kouchner was then a Red Cross worker who quit his organization in disgust at the way its neutrality prevented it from separating righteous from wrong. Another figure in this movement was a young French philosopher who liked to be photographed with his shirt unbuttoned to the navel, Bernard-Henri Lévy. A third was a Paris-based Brazilian student, Sérgio de Mello.

With no shortage of foreign crises onto which to project their vision, this small, charismatic group quickly grew into a worldwide movement. The new aid groups deployed to an earthquake in Nicaragua in 1972, a hurricane in Honduras in 1974, and set up refugee camps in Thailand for Cambodians fleeing the Khmer Rouge in 1975. In 1979, Kouchner filled a boat called L’Île de Lumière (The Island of Light) with doctors and journalists to sail the South China Sea administering to fleeing South Vietnamese boat people.

In the 1980s in Afghanistan, where Médecins Sans Frontières and a crop of other relief groups were patching up those wounded in the mujahedeen’s fight against a Soviet invasion, the humanitarians made a second, crucial evolution. The new thinking was that Western military power could be good if exercised righteously and in the cause of liberty. Might–in Afghanistan’s case the CIA’s shipment of billions of dollars of arms to the mujahedeen–could be right. Wars could be just.

Around the same time the aid workers’ ranks were swelled by a tide of celebrities. Famously, in 1984 the Irish singer Bob Geldof watched television news images of a famine in Ethiopia and underwent a conversion from angry rock star to curmudgeonly humanitarian. Geldof put together an all-star charity record, ‘Do They Know it’s Christmas?’, which raised £6 million for famine relief. Six months later Geldof staged Live Aid, simultaneous all-star concerts in London and Philadelphia that raised more than $100 million. Famous friends boosted the humanitarians’ impetus, and their self-regard. Do the right thing, stars urged in their campaigns. Be the right people. Be like us.

The spirit of Biafra was invoked once more in 1989 when a famine hit rebel areas of southern Sudan. In Biafra, civilian aid groups bringing in emergency relief had briefly made the landing strip at Uli the second busiest in Africa. Two decades later the UN and a small army of aid agencies did the same to a small airstrip in northern Kenya, Lokichoggio, using it as a base for Operation Lifeline Sudan, a mass airlift of millions of tons of food that ran for more than a decade.

The humanitarian cause suffered a setback in 1992–3 when a US mission to support a UN effort to address a famine in Somalia ended with ‘Black Hawk Down’. Televised images of the bodies of two dead US soldiers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu led to anguished questions. What were we thinking of? What were our boys doing there?

These were legitimate doubts. But 18 months later, when accounts of the Rwandan genocide began emerging, they were forgotten. Rwanda’s government had ordered the country’s Hutu majority to exterminate its Tutsi minority and in 100 days 800,000 people were killed, a tenth of the population. Though Rwandans had killed Rwandans, the horror of what had happened, magnified by a collective guilt at foreign inaction, persuaded many outsiders to focus on what they themselves had done wrong. Why had the world been so slow to step in? Why did foreigners always seem to fail Africa? Never again, the world resolved. Among the new disciples of international intervention was a young official at the National Security Council, Susan Rice, who had initially argued in favour of a UN pull-out from Rwanda. ‘I swore to myself that if I ever faced such a crisis again, I would come down on the side of dramatic action, going down in flames if that was required,’ Rice would later say.

If Rwanda seemed to make the case for forceful humanitarianism incontestable, the Balkans provided a first arena in which the world could demonstrate its new resolve. In 1999 in Kosovo, NATO bombed Serb forces out of concern for their Kosovan victims. It was no coincidence that de Mello, then Kouchner, both served as UN special representatives to Kosovo. Also present in the Balkans was a young reporter, Samantha Power. Based on her experiences, Power wrote a biography of de Mello and a Pulitzer Prize-winning book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide, in which she drew on Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia to sketch out a new emerging philosophy casting forceful humanitarian intervention as a moral obligation. A successful British operation in Sierra Leone in 2000 against rebels who used child soldiers to commit atrocities added further weight to the argument.

Though Power was initially moved by Serb persecution of Bosnia’s Muslims, the humanitarians soon found themselves in regular opposition to Islamists. In 1999–2000, de Mello took a job as UN administrator in East Timor where he vigorously repelled attacks by Indonesian security forces and Muslim militias on the Catholic East Timorese. In 2003 Bernard-Henri Lévy became one of the few Europeans outside the British government to offer qualified support to the US war on terror on the grounds that fighting Islamism, with its restrictions on women and free expression, was a humanitarian cause. After Kouchner became French Foreign Minister under the centre-right administration of Nicolas Sarkozy in 2007, he reversed France’s opposition to the war and the international fight against Islamist terrorism.

In the event, Iraq and the bloody sectarian chaos that ensued proved another setback. It also claimed de Mello’s life. Working as the head of another UN mission, this time in Baghdad, he was killed in the bombing of the UN headquarters in 2003 by an al-Qaeda group that claimed it was avenging de Mello’s actions against Muslims in East Timor. But the loss of one of their icons only redoubled the resolve of his peers. A UN World Summit in 2005 adopted humanitarian intervention–the ‘Responsibility to Protect’, or R2P–as official UN doctrine, vowing that never again would there be a Rwanda or a Cambodia or a Srebrenica.

R2P enshrined in international law the reason and duty for humanitarian intervention. This was a grand transformation in how the world worked. No longer would the UN issue empty criticism of repressive and incompetent governments. Henceforth if a government was excessively inhumane or inept, it would forfeit its sovereignty and the UN would be mandated to do better through diplomacy, sanctions or force. In many ways, R2P was a kinder, multilateral version of imperialism. Like imperialists, humanitarians presumed the West knows best. Like imperialists, they argued others’ sovereignty could be overruled in the name of civilizing them. Like imperialists, over time their interventionist instincts bent them ever more in favour of using military force.

By this time the humanitarians were also making inroads into other parts of the Western establishment. The same year the UN approved R2P, Samantha Power, now in academia, began advising a young US Senator, Barack Obama, on another interventionist touchstone, the war between Darfuri rebels and the Sudanese regime in Khartoum. Sudan had been a focus since Operation Lifeline Sudan. After 9/11 the activists’ numbers had been swelled by right-wing Christian Americans who characterized the conflict between south and north as one between Christian victims and Muslim oppressors. American evangelicals like Franklin Graham founded aid groups to which they gave names such as Samaritan’s Purse to assist the south. Republican Congressmen began flying in with suitcases of dollars to buy Christian slaves from their Muslim overlords. George Bush’s administration became the lead mediator in peace talks between Khartoum and Juba.

On Africa, Power worked closely with another rising US advocate of humanitarian intervention, John Prendergast. John had started his career in Sudan, writing excruciating reports for Human Rights Watch on the violence between rival southern militias. Under Bill Clinton, he switched to the government, working at the National Security Council as Director for African Affairs and as an advisor to Susan Rice in the State Department. After Clinton left, he switched back to non-government work, becoming an independent campaigner and publicist of some genius. He appeared frequently on television or before Congress, wrote books and editorials, and even advised the makers of the hit US television show Law and Order: Special Victims Unit on how to depict child soldiers and rape as a weapon of war. When he co-founded the Enough Project (‘the project to end genocide and crimes against humanity’), John used his standing to reach out to another centre of Western influence, Hollywood, helping recruit George Clooney to South Sudan’s cause, as well as his fellow actors Angelina Jolie (refugees), Matt Damon (water), Ben Affleck (Congo) and Don Cheadle (genocide and environment).

When Barack Obama was elected, the humanitarians’ reach into the US government was assured. The new President appointed Samantha Power as Special Assistant to the President in the State Department and a Senior Director at the National Security Council. He made Susan Rice Ambassador to the UN. John Prendergast became a frequent participant in White House discussions on Africa. In 2013, Obama promoted Rice and Power again. Rice became National Security Advisor and Power took Rice’s old job at the UN.

The humanitarians’ ascent to the highest office was complete. What began as an ideal inside the protest movement of the 1960s was, 50 years later, a cornerstone of Western foreign policy. This convergence between Western power and humanitarianism owed much to a mutual antipathy to Islamism. But it was also a credit to the commitment of its advocates, and there was no doubt, either, about the nobility of its goals: an end to suffering and war.

But even as the humanitarians were achieving new heights, South Sudan showed how short they could fall. International intervention had empowered a set of leaders whose behaviour quickly punctured any sense of triumph. The new ministers were accused of focusing on dividing up oil revenues among themselves. In 2011, several diplomats told me the government had stolen $14 billion in oil money since 2005, an allegation later repeated in public by Western diplomats and activist groups. In 2012, Kiir wrote to various government officials asking them to return $4 billion of it. In the same year, the south attacked the north and tried to steal the few oil wells Khartoum had retained after independence.

There were other signs of thuggery. Journalists were beaten, imprisoned and killed. A new constitution drawn up by President Salva Kiir granted him authoritarian powers. Worse, many southern leaders were turning on each other. Even before the Dinka-Nuer war erupted, thousands were dying every year in tribal clashes over land and cattle. The new government left aid workers to deal with some of the worst levels of health, education and poverty in the world–though, since two-thirds of the southern government was illiterate, that, at least, was partly justified.

For their part, the aid workers might have set an example with impressive results. They didn’t. In 2005, South Sudan’s donors had established a $526 million fund to get the country on its feet by paying for roads, running water, agriculture, health and education. Four years later, it had only spent $217 million of that. A World Bank investigation discovered its managers were apathetic and out of their depth. They had held up any spending for a year, for example, before explaining to the new government that it would need to open a bank account before payments could be made.

Then there was the UN, with its budget of $924 million a year and its 70 fortified bases across the country. It did not escape the notice of the South Sudanese that the single biggest infrastructure project in their new country–what South Sudan lacked above all else–was housing and offices for foreigners. Every time I returned to South Sudan, I heard ever more anger at these giant air-conditioned, razor-wired moon-bases on the edge of every town, which managed the neat trick of simultaneously focusing the UN’s efforts and resources on itself while cutting it off from the people it was meant to assist. The bases seemed to symbolize the dilemma confronting all assistance. By designating one people as able to help and another as in need of that help, empowerment programmes could disempower. The very endeavour of trying to lift a people up could reduce them. With its riot fences and armed guards, the UN was presenting the South Sudanese with unassailable proof that it was on the wrong side of a line separating privilege from poverty.

South Sudan threw up other contradictions. It turned out that freedom, by its very nature, couldn’t be shepherded on another’s behalf. When South Sudan’s leaders interpreted their new freedom as the freedom to kill each other, and the world reacted with horror, Kiir and others accused them of misunderstanding what they had helped create. Freedom meant freedom from everyone–from Khartoum, yes, but also erstwhile friends if they tried to take that freedom back. In this newly free country, even in a far from fully formed one like South Sudan, the world had much less influence than it imagined. President Kiir was especially intolerant of suggestions that he owed anyone. ‘I am not under your command,’ he told Ban ki-Moon in 2012 when the UN Secretary-General urged him to end his brief invasion of the north. ‘I am a head of state accountable to my people. I will not withdraw the troops.’ Likewise when the world demanded an end to the Dinka-Nuer fighting, Kiir’s government staged mass rallies outside UN bases across the country demanding the foreigners leave. When Hilde Johnson, the Norwegian head of the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), protested at the way UN relief convoys were being harassed and delayed, Kiir accused her of trying to supplant him. ‘Hilde Johnson and the UN are running a parallel government,’ he said. ‘They want to be the government of this country.’ When aid agencies began warning of a looming famine, Kiir’s government responded by telling the foreigners to leave. Four out of every five of the top jobs in foreign agencies and businesses would be reserved henceforth for South Sudanese.

It seemed possible that humanitarianism had reached a high-tide mark in South Sudan. In private, diplomats in Juba worried that if South Sudan was humanitarianism’s fullest ever expression, its woeful failure put the whole doctrine in doubt. However noble the ideals, however high the ambitions, they were ruined by calamitous implementation. ‘State-building was a total disaster,’ one senior UN official conceded. ‘It was just full of words and hardly any delivery, fragmented, weak and all over the place. It simply didn’t deliver what the country needed.’

When I phoned him from Juba, John Prendergast said any expectations that South Sudan would experience a smooth birth ran counter to the violent norms of human history. But it was also true, he said, that South Sudan showed that the way the world pursued international intervention ‘is crushingly flawed and will never make a difference unless it’s altered. You have this plan where humanitarians are dispatched to help build a state–and they run smack up against political forces that have no interest in long-term peace and stability, that benefit from instability and no transparency. [The humanitarians] work on development before the war is over. They work with governments that are completely unreformed. The rebels are integrated into a national army without reform, so their predation continues. These are utterly fatal flaws. At this point in South Sudan, everybody has failed at their function.’

The world’s weaknesses only became more evident once the violence started. In March 2014 the UN Security Council upgraded UNMISS’ mandate from state-building to something more urgent: ‘protecting civilians; facilitating humanitarian assistance; monitoring and reporting on human rights; preventing further inter-communal violence’. In reality, the UN seemed unable or unwilling even to protect its own bases, let alone venture out to stop the killing. ‘These forces were sent for state-building, not war,’ said John. ‘You need to get troops that are willing to fight.’

The emergency aid effort was also insufficient. In mid May, when the rains began, cholera swept Juba, killing more than 130 and infecting close to 6,000, among them refugees camped outside the UN’s main base. After that came an epidemic of malaria. Famine was said to be only months away. UN Secretary-General Ban ki-Moon warned that in a worst-case scenario, ‘half South Sudan’s 12 million people will either be displaced internally, refugees abroad, starving or dead by the year’s end’.

Maybe, sighed a few veteran diplomats in Juba, the answer was simply to pull out. Asked what the world had accomplished in South Sudan, one Western diplomat with three decades of experience in Sudan replied: ‘I would say we have saved a lot of lives.’ But it was fair, he said, to wonder whether two generations of efforts to teach South Sudanese leaders how to care–how to provide food and education and health–had had the opposite effect. Had aid taught South Sudan’s leaders they didn’t need to bother? Had it enriched them and allowed them to build the forces now slaughtering their own countrymen? ‘Did we create this?’ asked the diplomat. ‘If we had bailed out 20 years ago, would the country be more politically mature now? Probably, yes.’ At one point, I noticed the man was struggling not to cry. Seeing Mading and me out through the steel gates of his high-walled compound in Juba, he said: ‘I honestly don’t think anybody here has any answers any more.’

Humanitarianism was being ruined by incompetence and indifference within the rank and file on whom it relied for implementation. But among its leading advocates in the UN and aid industry, I began to see humanitarianism’s problem as one of character–or, rather, a problem of great character. Its disciples believed in freedom. They strove for the poor and unfortunate. They took on projects of almost impossibly high ambition and often put the happiness and welfare of strangers before their own. This idealism was admirable. But it made them easy meat for the lesser characters in whom they placed their trust. ‘They get caught up in the romance,’ said Peter Adwok, a former Cabinet minister fired by Kiir. ‘They believe the best of people. They can’t imagine their friends ordering people thrown out of the back of a helicopter.’

The humanitarians’ high ideals seemed to limit not just their effectiveness but their imaginations too. By positioning themselves as the protectors of all, they set themselves up for certain failure. And yet their character was such that, whatever the doubts and misgivings and setbacks, there was no question of quitting. Confronted by catastrophe in South Sudan, I heard scores of US diplomats, UN officials, aid workers and activists accept responsibility, confess they should have done more–and refuse to be deterred. Failure was no reason to doubt the cause. On the contrary, the history of how humanitarianism grew from the margins to become orthodoxy proved the value of steadfastness. Almost all their suggestions for South Sudan were about doing more of the same: more aid, more peacekeepers, firmer sanctions on South Sudanese leaders, a bigger UN presence. Hilde Johnson stressed the enormity of the task still ahead. ‘A peace agreement is just a few signatures on a piece of paper,’ she said. ‘Actual peace starts the day the signatures are dry.’

Frustrated by those they had tried to help, it was easy to see how the urge to do something might become an urge to take over. To hear some talk, the best way forward was to take South Sudan back to an earlier era. When I called her in Washington, the US Ambassador, Susan Page, initially insisted foreigners should be confined to a supporting role but soon switched to talking about how to impose international will. ‘Right now [the question is] how do you get a country of 10 million people to reconcile even when war and ethnic conflict continue to exist?’ she said. Some diplomats in Juba were discussing restarting Operation Lifeline Sudan. Many were passing round an article in the Atlantic magazine that argued for a kind of humanitarian colonialism, doing away with South Sudan’s government altogether and creating a UN or US protectorate until South Sudan could be trusted to rule itself. ‘The solution to these problems is not to send in more peacekeepers… or hammer out a power-sharing agreement between the warring parties–or rather, not only to do these things,’ wrote Pascal Zachary, an Arizona University lecturer in African affairs. ‘The response to South Sudan’s turmoil should be crafted with a set of policy tools that were popular in the 1950s… the process known as “trusteeship”, whereby a newly independent nation is granted special forms of assistance and special constraints on sovereignty. In some cases, the former colonial power sought to administer the trusteeship, and in other cases an international coalition or the United Nations did so.’

Even before South Sudan fell apart, George Clooney had had his doubts about how things would turn out. ‘I’ve spent a lot of time with the South Sudan government,’ he said. ‘I have faith in them. But could it fail? Without question.’ But, like his fellow humanitarians, his uncertainty only redoubled his conviction. ‘What I do know is it will most definitely fail without the entire world’s effort in trying to help it,’ he said.

When I asked Clooney why he kept coming back, he admitted it was partly about what he got out of it, the way it made him feel. ‘The truth,’ he said, ‘is I think any human being, once they participate in something that’s bigger than themselves and something that you can’t fix yourself… the idea that you wouldn’t continue… you would feel as if you had done something terrible, you’d abandoned them. So you have to continue.’

After World War II, Africa rose up against foreign interference. Since the turn of the millennium, a new wave of African assertion has once more gathered pace. But there will always be those Africans who, for their own reasons, ask foreigners to intervene. Clooney mentioned that one South Sudanese official to whom he was close was Ezekiel Lol Gatkuoth, South Sudan’s former Ambassador to the US. In 2014 Ezekiel was on trial in Juba for treason, accused of helping instigate the violence in December. He was being kept under lock and key except for the occasional court appearance. One of those fell on a day when Mading and I were in the city.

We arrived early, positioned ourselves at the court entrance and, as Ezekiel swept past in a cloud of soldiers and assistants, Mading slipped a note I had prepared into the hand of his lawyer. I had written down a handful of questions, chiefly about what Ezekiel thought the world should do next. ‘Some say the world should pull out,’ I wrote. ‘Some argue for more intervention. What do you think?’

The lawyer returned the note the next day, with Ezekiel’s replies scribbled under my queries. The disaster in South Sudan had a clear solution, said Ezekiel. ‘George Clooney must get more engaged now to help shape the future of this country,’ he wrote.