FOUR

UGANDA AND THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC

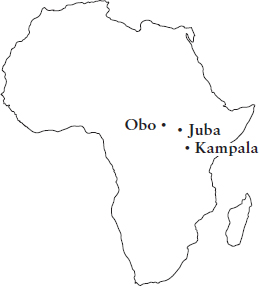

Leaving Juba and travelling due west towards the centre of Africa, humanity thins then all but disappears until the world seems to be nothing but thorn forest and scrub, stretching in every direction to the horizon. After 700 kilometres, you come to the town of Obo, which lies in the bend of an unknown river in a nameless forest in a country whose name–Central African Republic–is generic. A few kilometres from Africa’s Pole of Inaccessibility, its furthest point from any ocean, it is about as remote a place as exists in the world. Obo’s 15,000 residents build houses of cane and palm thatch, have neither power nor running water, and come together at the town church to which the priest still summons them by banging a stick on a wooden drum. Outside town, in any direction, are hundreds of kilometres of unbroken forest, home to nomads, pygmies and hippos.

There were almost no cars in Obo but there were motorbikes. Dominic and I hired a pair and followed the single road through town to its western edge. A sidetrack led past a police post to which a baby chimpanzee was tied by a string. Past it, the path ended on a bluff overlooking the river on which there was a new construction: a two-metre-high reed fence inside which were several grass huts. There was a guard outside. I scribbled my name on a piece of paper, handed it to the man and asked him to take it inside. Seconds later two stern white faces popped up on the other side of the fence. ‘You’re not allowed in here,’ said one, in an American accent. ‘Speak to public affairs in Entebbe.’ And the faces disappeared.

What were 30 US Special Operations soldiers doing in one of the most far-flung places on earth? Special Ops’ customary secrecy notwithstanding, their mission was on public record. In May 2010, Congress passed the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act, mandating President Barack Obama to ‘eliminate the threat to civilians and regional stability’ posed by the LRA. In response, Obama said he would back African efforts to ‘apprehend or remove’ LRA leader Joseph Kony. He duly deployed 30 Special Operations troops to the Central African Republic and 70 more to Uganda, Congo and South Sudan. Two years later he doubled the force and equipped it with four Osprey search aircraft.

To which a reasonable question was: why?

The Lord’s Resistance Army had its origins in a devout Christian group called the Holy Spirit Movement founded by a woman called Alice Auma in Gulu, northern Uganda, in the early 1980s. Alice belonged to the Acholi tribe and earned her living as a spirit medium, diviner and healer. In 1985, at the height of a bloody civil war that would see Yoweri Museveni win power, she was possessed by the spirit of a dead Acholi soldier whom she called ‘Lakwena’, meaning ‘messenger’. Lakwena instructed Alice to give up her work, which Lakwena said was pointless in war, and concentrate on trying to end the bloodshed. She was to do this by forming the Holy Spirit Movement, with which she would recapture the Ugandan capital, Kampala, from Museveni.

In 1987 Alice marched south towards Kampala. She had thousands of followers and picked up more support en route from other anti-Museveni rebels. But Lakwena had instructed his followers to arm themselves only with sticks and stones and smear themselves with shea nut oil to protect themselves from bullets. Outside Kampala, the movement was obliterated by Museveni’s artillery. Alice fled to a life of exile in a Kenyan refugee camp. Joseph Kony, one of the movement’s commanders, gathered up the few survivors, led them back to the north and disappeared into the forest, where he renamed his force the Lord’s Resistance Army.

Kony’s modus operandi was terror and his brutality made him a grotesque caricature of a bloodthirsty African rebel. He ordered his fighters not just to rape and murder but to mutilate and eat parts of their dead enemies. Most of his soldiers were children and he sustained his forces’ strength by pillaging villages to abduct more. That was also how the LRA leader found his wives, of which he soon built up a harem of a few dozen.

Evil isn’t a useful word–it is dismissive and obscures understanding–but in Kony’s case it was a description he embraced. One LRA deserter in Obo, 33-year-old Emmanuel Dada, said he had been abducted by Kony from his village and forced to fight and kill for the LRA for several years. Dada remembered a sermon the leader once gave. ‘Kony told us: “The Bible says if you are going to do good, do good all your life, and if you are going to do evil, do evil all your life,”’ recalled Dada. ‘“I chose evil and that’s what I will always do.”’

Kony had long since given up trying to oust Museveni. Over the years the LRA had wandered from Uganda into South Sudan, Congo and the Central African Republic. After a December 2008 assault on the LRA’s main base in Congo, Kony split the LRA into tiny groups and scattered them as far as Darfur. He pursued a bloody campaign of annihilation against any villagers he came across, not just stealing food and abducting children but carrying out a series of massacres too. ‘I killed too many to count,’ Dada said. ‘They forced me to kill an old man. He was just doing nothing, just sitting there, and I beat him to death with a stick.’

After 26 years of marauding through the central African bush, the cumulative damage inflicted by the LRA was staggering. Despite never mustering more than a few thousand fighters, and generally no more than a few hundred, the UN said the LRA had killed tens of thousands, abducted 30,000 and displaced 1.5 million.

Of all the rebel groups on the continent, the LRA conformed most closely to rich-world nightmares of African savagery. Perhaps it should have been no surprise, then, that it attracted some peculiarly imaginative Westerners to fight it. One day I visited an orphanage in a town called Nimule on South Sudan’s border with Uganda. The place was a crumbling collection of 18 windowless brick and tin-roof buildings including dormitories, school halls and a cafeteria housing around 200 children. A sign indicated it was run by the World Mission Shekinah Fellowship, an evangelical church in Central City, Pennsylvania, with support from other charities. There was nothing to suggest the presence of the man who founded it, Sam Childers, aka the Machine Gun Preacher.

Childers has written two books. He titled the first Another Man’s War: The True Story of One Man’s Battle to Save Children in the Sudan. The second he called Living on the Edge–Something Worth Dying For, the Children of Africa. The first book was made into a movie, Machine Gun Preacher, starring the Scottish action hero Gerard Butler. The books, the movie, plus Machine Gun Preacher T-shirts, caps, shot glasses, dog tags, keyrings and beer coolers, as well as a selection of photographs showing Childers on his Harley-Davidson in checked shirts sawn off at the shoulder, chewing a toothpick through his walrus moustache, are available on Childers’ website. The subject of all this merchandise never varies: Sam Childers.

Childers is a former drug dealer and biker turned born-again Christian who in the late 1990s made it his one-man mission to save ‘Africa’s orphans’ from the LRA. The poster for Machine Gun Preacher, the movie, depicted a stern-faced Gerard Butler in black jeans, black T-shirt and black beard, his legs astride an African shanty town, one hand gripping a Kalashnikov, the other protecting an African urchin in rags. In the film, Butler growls to a Sudanese boy with whom he is sitting outside a mud hut: ‘Helping you kids ’sbout the only good thin’ I ’ver dun ’nthis life.’ A few seconds pass. ‘You got no idea what ’msaying, dooya?’ says Butler.

It turned out that few of the villagers living around Childers’ orphanage had any idea who he was, either. I went to five or six huts, then asked around in a few shop stalls. Everywhere I drew a blank. Nobody knew the kawaja. Some said they had seen him once or twice but added he only came to the orphanage every few years. No one could give any credence to Childers’ claim to be single-handedly fighting the LRA.

Eventually, I found Festo Fuli Akim sitting out in his front yard taking the afternoon air. Festo was 80. He knew Childers. He thought the orphanage was a good idea. Festo had helped Childers obtain the necessary permissions to start it. He found him a plot of land. He gave him several truckloads of bricks. And at first, the orphanage seemed to fulfil a need. But within a few years, it was collapsing. Festo claimed Childers was struggling to finance the place. The orphans were malnourished and had only rags for clothes. Other aid agencies began bringing in food and shoes. ‘The children were always breaking out and eating my mangoes and guavas,’ said Festo. ‘They were in bad shape.’ Childers denied the orphans suffered and blamed others for misusing funds.

After an LRA attack on Nimule, however, Childers hit upon a scheme to raise attention and money. ‘He took the orphans to a river camp some way away from here,’ said Festo. ‘He trained them. He dressed them in camouflage uniforms. He armed them. He pretended that one group was LRA and that he was trying to rescue children from the LRA. He took pictures of himself. He had a documentary made about himself.’ But when they returned to Nimule, the children told the villagers what Childers was up to. Policemen raided the orphanage and found four guns. Childers was asked to leave. Festo sighed. ‘Sam is a complicated man,’ he said. ‘He always talked big, big big. He thought he would become famous. A commander.’ Childers has denied these allegations.

I wanted to hear Childers’ explanation for his actions but he ignored my attempts at contact. I did find some account of his motives in the opening pages of his second book, Living on the Edge. It began with ‘I, Sam Childers, the Machine Gun Preacher’ riding his Harley to a Hollywood Oscar party, celebrating the release of the film. ‘It’s a movie about a man who does his best to take care of people who can’t take care of themselves,’ wrote Childers. At the entrance to the party, Childers described how his appearance–‘big moustache, biker tattoos, leather from head to toe’–gave the doorman pause, only for his eyes to widen in amazement when Childers pointed out the words ‘Machine Gun Preacher’ on his guest list. The doorman then stepped aside and Childers strutted into the party. ‘In a few minutes, I was shooting the breeze with George Clooney,’ he wrote. ‘It made perfect sense to me.’

Over the years, Africa has received its share of foreigners on a quest for what Carl Jung called individuation: discovering themselves by being out in the world. It is an old story–the stranger who becomes a hero to the people of a faraway land–and in the rich world, it is generally regarded as a laudable rite of passage. And, it is true, the desire to make a difference can sound commendable.

The problem arises when questions of who to help, and why, are left as secondary. This is how Africans become bit players in their own story. There is no room in this picture for Africans who can look after themselves or control their own destiny. There is no recognition of the zero-sum maths of how fulfilling Westerners’ desire to do something can rob Africans of the ability to do it for themselves. There is little understanding of how viewing Africa simplistically encourages some dangerously simple solutions. Feed people. Clothe them. Starve the terrorists. See how straightforward Africa’s problems have become.

Most aid workers laughed through Machine Gun Preacher, which became a kind of cult hit on the NGO circuit. But how different was it from The E-Team, a 2014 documentary on the ‘high-stakes work’ of Human Rights Watch’s ‘emergency team’? ‘Though they are very different personalities, Anna, Rwigema and Peter share a fearless spirit and a deep commitment to exposing and halting human rights abuses all over the world’, read a publicity release featuring a poster of the three, looking every bit as rough-travelled and righteously furious as Gerard Butler. One of them was Peter Bouckaert, ‘a savvy strategist and fearless investigator… “the James Bond of human-rights investigators”’. I knew Peter, who had been a neighbour in Cape Town. He was dedicated, good company and publicized appalling acts in tough spots. I can’t say he ever reminded me of James Bond.

The humanitarians’ licence to honour themselves derived from their assertion that they were championing universal values. The justice of their causes was undeniable, they said. And the way humanitarians presented them, it was hard to object. How could you be against Saving the Children?

The trouble was the way the children–actually fully formed adults, in the main–insisted on leading more complicated lives than black-and-white didactics allowed. Take the vow from clothes manufacturers like Nike, H&M and Walmart’s Baby George line that they would only use organic cotton, and thus instantly transform the fortunes of Uganda’s low-tech cotton farmers who would become prosperous, green pioneers. Was there a better win-win? Unlikely, it seemed, until you considered that Uganda’s central villages also had the world’s highest concentration of malaria, and that organic certification required a ban on mosquito-killing insecticides. A trip I made to the most malarial town on earth, Apac in northern Uganda, confirmed a dreadful suspicion: African babies were dying so that Western babies could wear organic.

Simplification can aid understanding. It can also impede it. And in the imaginary, curiously flat Africa of the humanitarian, the people are one-dimensional objects awaiting rescue or upliftment by kindly foreigners. Any recognition of them as fully realized individuals with normal, intricate lives is lost. Africa becomes an exotic, bizarre, violent place, without past or context, a place of good guys and bad guys, simple problems and universal solutions. It’s only a short step from there to regarding Africa as a place that is essentially negative, where half-humans live half-lives, life is somehow cheaper and where foreigners shrug at black misfortune as another example of ‘TIA’–This is Africa. This Africa is a place without history, where wars erupt out of nowhere, over nothing, and Africans fight and die all the time, for no good reason. War just is, because Africans are. The more incomprehensible and cease-less the dying, the more heroic the effort to help. This is an Africa where, as the New Yorker correspondent Jon Lee Anderson puts it, the people have become ‘killable’.

After Obo, I flew to the US to find out why the government had decided it should try to kill Joseph Kony. It was then that I first met John Prendergast. John said the reason for the US interest was down to an extraordinary new ‘social movement of mostly young people attempting to address a moral issue halfway round the world which had little or no ramifications for them’. John thought it was amazing. ‘How many people responded to the call!’ he said. ‘It’s revitalizing.’

The movement was Invisible Children. It was founded by three Californian students: Bobby Bailey, Laren Poole and Jason Russell. They set up the group in March 2003, a time when they were, respectively 21, 19 and 24. Invisible Children’s origins were easy to trace because, with some foresight, its three founders had filmed them for their own documentary. At the beginning of the film, they gave charmingly inarticulate explanations for why three hipsters with goatees and baseball caps might be setting off for Africa to make a film about a 47-year-old civil war that had cost two million lives. ‘We are naïve kids that have not travelled a lot and we are going to Sudan,’ said Bobby Bailey. Laren Poole rambled about how ‘media is life, it defines your life. So it’s an obvious choice for three kids who want to find the truth… ’. In a voice-over, Jason Russell added: ‘None of us knew what we were doing.’

As the documentary recorded, the three made it to Sudan but failed to find the fighting. After filming themselves vomiting, setting anthills on fire and chopping a snake in half, they followed a trail of Sudanese refugees south across the border into northern Uganda. When they approached the town of Gulu, a truck in front of them was shot at and two people were killed. Forced to stay in Gulu overnight, they filmed as thousands of children showed up after dark, sleeping on street corners, in a bus park and in the corridors of Gulu’s hospital. ‘Needless to say,’ narrated Jason Russell, ‘we found our story.’

The three friends had stumbled across the fallout from the LRA’s war: thousands of children too afraid to sleep at home because of the risk of being abducted. The Californians stayed two months and ended by vowing, on camera, to return. Back in San Diego they cut their documentary and called it Invisible Children. To maximize its impact, they took their film on the road themselves, screening it to hundreds of thousands of students at high schools and college campuses across the US.

So far, so do-good. But Invisible Children was different from other campaign groups. Young, privileged and goofy, their DNA was more selfie than selfless. They broke with convention, horrifying old Africa hands by making a film that was as much about themselves as the war, discarding any notion of neutrality and paying no lip service to concerns about interfering in the sovereign affairs of a foreign country. While military action was anathema to most of the aid world, Invisible Children demanded it. When I spoke to Jason Russell and Ben Keesey, Invisible Children’s 29-year-old CEO, the pair said the established model of international intervention, addressing needs for food and shelter but ignoring the political cause, was merely a way of ‘managing pain’ but not fixing it. Ben said even the most aggressive form of foreign intervention, UN peacekeeping, had been ineffective in Darfur, Congo and Sudan because it was done by developing-world armies with no stake in the fight and no peace to keep. That left robust Western–preferably US–military action.

In many ways, Invisible Children was humanitarianism taken to its logical end point. Its philosophy and supporters were largely Christian. The self-absorption the group displayed–and which Sam Childers had taken to such delirious heights–had dogged the humanitarian movement from the start. The question of deploying armed force was another long-standing paradox. It was the most forceful way of enforcing international goodwill, but it also meant giving up the moral high ground and that, for most, was a step too far. Childers didn’t care about any of that, nor did Invisible Children. ‘That’s really old-school,’ said Jason. Invisible Children wanted action. The ends justified the means. ‘What’s more humanitarian than stopping a war?’ asked Jason. ‘I understand the conviction that violence begets violence. But either you just go on pulling people out of the river or you go upstream, find out who is pushing them in and stop them. And that’s not about Kumbaya concerts for world peace.’ Jason said he would prefer Kony captured alive and tried, not killed. But he was realistic about how unlikely that was. ‘This is a war,’ he said. ‘We’re not hoping for rainbows and butterflies.’

Invisible Children wanted US military action to finish off the LRA. They were surprised when they didn’t immediately get it. Their film did generate impressive support, though, enough to provide funds for eight further documentaries. A team of what grew to 60 volunteers then toured across the US, screening their new films to total audiences of up to a million, drumming up more support and more donations. Within a few years, Invisible Children had made the LRA a key foreign issue for American students. But however much publicity the group garnered, it didn’t solve anything. ‘In our world,’ Jason said, ‘abducting children, cutting people’s faces off, making children eat their friends–that just doesn’t happen. We thought: “Once people know about this, it’s going to end in a year.”’ It didn’t. Which was when Invisible Children linked up with John Prendergast as their big gun in Washington.

By the time of Barack Obama’s election, John’s links to the celebrity world were without equal. Perhaps more than anyone, he had helped kick off a new era of superstar advocacy. When a Republican president gave way to a Democrat one in 2009, it sealed John’s influence. His ties to the new administration were manifold. He was a former advisor to Susan Rice, by then US Ambassador to the UN. From their work together on Darfur, he was also friends with Samantha Power, by then advisor to the National Security Council. John had also co-founded the Enough Project with Gayle Smith, now Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director at the National Security Council. The President was even a former community organizer himself.

With the access and influence at his command, John took the energy that Invisible Children had stoked and focused it on Washington. He drew up a punishing schedule of meetings with Senate and Congressional leaders, and White House staffers. John’s stance was unequivocal. The LRA should be bombed, he said. By 2009, John and Invisible Children had made impressive progress and were helping draft a Congressional Act demanding presidential action against the LRA. By early 2010, a time of corrosive partisanship in Washington, the anti-LRA group had secured cross-party Congressional backing for the LRA Act and in the Senate co-sponsorship from conservative Sam Brownback and liberal Russ Feingold. Whenever the legislation hit a speed bump, Invisible Children overcame it through sheer numbers. At one point Senator Tom Coburn, a Republican known as ‘Dr No’ for blocking legislation on budgetary grounds, tried to kill the bill. That was a cue for 100 Invisible Children activists to sleep in the car park outside his office for 11 nights in snowy, midwinter Oklahoma until he relented.

At first glance, the saga of how three Californian backpackers persuaded Obama to deploy 100 Special Operations soldiers to central Africa seemed the ultimate wag-the-dog story. If that was the case, it raised some profound questions about the US political process and, in particular, how America decided to go to war.

But as the LRA campaign gathered pace, John said that though the White House shared his humanitarian goals, Obama was revealing he had additional reasons for backing it. One was smart politics. Throughout their lobbying, John said he and Invisible Children were quietly encouraged by the White House–by Power, Rice and Obama himself. ‘You make it an issue for young people, a community who vote, and he will take that seriously,’ said John. ‘He’s very aware of the scope of movements.’

Another motive was smart counter-terrorism. At the heart of Obama’s remade US foreign policy was a belief that after the Bush years, in which American soldiers had garnered a reputation as hegemonic, vengeful bullies who loved oil and hated Muslims, it was in the best US national interest to present America itself as the ultimate humanitarian, an all-round international good guy. In another era, aid groups in Afghanistan had argued that the humanitarian project could be writ large, and extended to governments or armies. Obama was reaching back further still, to the pre-humanitarian Cold War, and arguing, once again, that being righteous had strategic benefits for the West. And in the twenty-first century, he proposed that the US military would take a leading role. They would continue to protect the US directly with force. But they would also do so indirectly, by representing America as a benign force out in the world, doing good by being good.

In April 2013, the Sudan scholar and former Africa activist Alex de Waal wrote that he had become ‘rather uncomfortable’ with the humanitarian movement, ‘not because I had diluted my personal commitment to working in solidarity with suffering and oppressed people but because a group of people, in whose company I didn’t want to be, were claiming not only to be activists but to define “activism” itself’. De Waal decried the policy lobbyists and ‘designer activists’ in Washington who now endorsed African causes. ‘It was no accident,’ continued de Waal, ‘that their purported solutions placed the “activists” themselves at the centre of the narrative, because many of them were Hollywood actors–or their hangers-on–for whom the only possible role is as the protagonist-saviour.’ And if the way these activists supplanted Africans as guardians of African interests was plain wrong, said de Waal, a new low was how the actions they proposed all had one thing in common: ‘using more US power around the world’.

John and Invisible Children had been pushing at an open door. By the time Congress passed the LRA law, Obama was telling John he planned to stretch its wording as far as possible–even to the extent of interpreting the words ‘eliminate the threat’ to mean US boots on the ground. John didn’t particularly care what anyone’s reasons were for joining the fight. Whatever worked. That didn’t mean he hadn’t noticed them. ‘We suddenly got the feeling that anything was possible. We never asked for troops on the ground. But they went further than anything we were advocating. And this is not a decision by underlings. This is a decision by the President.’

This was what de Waal meant when he said activism had been hijacked in the name of US power. It was the kind of thinking that led Rice, Power and Obama to push the argument inside the White House in favour of attacking Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in Libya to protect pro-democracy rebels. The operation against the LRA was an even fuller example of the US military’s new righteous pose. In early 2012, just as I was travelling to Obo, Obama chose the National Prayer Breakfast to give a detailed explanation of his new thinking on how to wield US power overseas. ‘When I decide to stand up for foreign aid, or prevent atrocities in places like Uganda,’ said Obama, ‘it’s not just about strengthening alliances, or promoting democratic values.’ It was also about ‘the Biblical call to care [and] projecting American leadership around the world. It will make us safer and more secure.’

At its most damaging, humanitarians’ self-regard encouraged them to appropriate African autonomy. They defined Africa’s problems and imagined their solutions. What was meant to be about them ended up being about you.

Employing the US military as armed humanitarians wrote that in stone. Constitutionally, the President could only use the US military for US national defence. This is how foreign military adventurism and foreign compassion, two belief systems that might at first sound very far apart, could come to intersect. This is also how a group of aid workers might get themselves mixed up in an American plot to cause a famine in pursuit of a few thousand Islamists.

On 5 March 2012, Invisible Children released a 29-minute internet film, their tenth, called Kony 2012. The idea behind it was to encourage Invisible Children’s followers to make Kony the most famous war criminal on earth. That would, they said, raise the necessary political will to arrest or kill him.

The film was well made, slick and emotive. It featured Jason Russell’s five-year-old son, Jake, as he grappled with the notion of Kony’s killings and kidnapping of child soldiers. Another star was a Ugandan boy, Jacob, who cried as he called for Jason’s help. Jason duly pledged it. Invisible Children had wanted 500,000 website hits. They got a million in 24 hours. After 48 hours they had a million every 30 minutes. Six days after its release, 85 million people had watched the film, by then translated into 50 different languages.

Depending on your view, Kony 2012 was either stunningly innovative, a whole new type of campaign, or recklessly manipulative and inaccurate. There was no doubt that conventional aid-group campaigning, the old black-and-white pictures of starving babies, suddenly looked desperately tired. Effusive backing came from a host of American Senators, Congressmen and celebrities. International Criminal Court Chief Prosecutor Louis Moreno Ocampo told the BBC: ‘They’ve mobilized the world.’

The contrary view was that Invisible Children had made a film glorifying their own desire to save others and, in the process, simplified and sensationalized the LRA conflict. Academics and bloggers, particularly Africans, criticized the group for overstating the threat–with 150–200 mostly barefoot fighters, the LRA had never been weaker. Older, more established campaigners grumbled that Invisible Children’s support for armed intervention conflicted with the foundation of a human rights organization. By personalizing the narrative of Kony 2012 with Jason Russell’s own family, they added, Invisible Children had exposed their true motive: self-aggrandizement. Ugandan video-blogger Rosebell Kagumire became a web hit herself when she attacked Invisible Children for casting themselves as ‘heroes rescuing African children’ and Africans as ‘hopeless, voiceless’.

Jason now became the target of a deeply personal, bullying online ‘takedown’. I called him eight days after Kony 2012’s release. He told me he hadn’t slept for a week. The film was ‘changing the world’, he said, but at the same time ‘people are calling me the devil’. Three days later, Jason was found by the San Diego police naked and kneeling on the side of a busy highway, raising his palms to Heaven and slapping the pavement. He was diagnosed with exhaustion and admitted to hospital.

Six months later Invisible Children released a new Kony film. Jason, now out of treatment, featured as extensively as before. He embarked on a series of prime-time interviews, including an appearance on the The Oprah Winfrey Show, to explain his behaviour. He looked well, if a little chastened. But the breakdown had done nothing to dim his enthusiasm for the mission. On the contrary, he seemed to view his collapse as a wondrous, terrifying breakthrough. ‘I literally thought I was responsible for the future of humanity,’ he told one interviewer.

In the autumn of 2013, Invisible Children convened what they titled a Fourth Estate Summit at the University of Los Angeles campus in California. For $495 for an all-inclusive four-day ticket, participants could take part in an event ‘where the future of justice is shaped by you’. Jason was MC. The star speaker was Samantha Power. A new addition to the Invisible Children leadership was Jedidiah Jenkins, described on the group’s website as its ‘ideas maven’.

On stage, Jedidiah talked about how Invisible Children saved him from law school–‘I felt the liberty of it, I couldn’t get it out of my system, I became addicted to it’–and was now ‘empowering’ him to bicycle from Florence, Oregon, to Patagonia, South America. ‘I’m on that search for identity, what makes us who we are,’ he said. ‘Once you know that you are worthy, and that you matter, you are so liberated to liberate others. We want to make sure you guys know what’s up, what it’s all about. Because when you fight for Jacob, when you fight for zero LRA, you’re discovering yourself, you’re building your heart.’

Jason introduced Samantha Power. Over a short film of her life, he narrated how the ‘world-famous’ holder of ‘one of the most important positions in the world’ had ‘discovered her passion for human rights’ in Bosnia. ‘What she saw there changed her for ever and inspired her to dedicate her life to ending extreme human rights abuses.’

Power appeared in an orange and black evening dress to a standing ovation of cheers, claps and camera flashes. She clapped back. ‘OMG,’ she said. ‘Right back atcha. I had a hunch that this would be inspiring. But this is something else.’ Over another round of whooping and whistles, she began: ‘So as you heard, I just began serving as US Ambassador to the United Nations… ’–more applause–‘… and I thought: “Where should I give my first speech?” There was only one answer. As you know, you are not just any group of young people. You are young people who take very seriously the charge to love your neighbour as yourself. Young people with a moral imagination. Young people on a mission. Young people who are determined to leave this world kinder than the world you found.

‘Though the odds are against you, you’re going to offer whatever you have, your voice, your time, your creativity, your skills, your determination to try to help people. Because it turns out you have the power! If you’ve ever doubted that your activism matters, thanks to you the State Department is offering the first cash rewards to bring the LRA killers to justice!’

At that, the cheering began to raise the roof. ‘That’s you! You! The most powerful weapon of all is you! We need your positive moral vision more than ever. We need your vision of justice to win over those who fear it. We need your vision of freedom to overwhelm those who rely on repression. We need your vision of equality and tolerance to overcome those who propagate division and terror. And we need you to act so that that vision, your vision, prevails. You’re not just activists. You’re leaders. You’re diplomats. It is your time!’

Power spoke for 20 minutes. When she finished, the crowd jumped to its feet for a second standing ovation. Jedidiah and Jason appeared on stage behind Power, raising their hands and applauding. Jason seemed entranced. ‘I used to think that God did not make perfect people,’ he said. ‘I’m very wrong tonight.’ Jedidiah might have been in love. ‘Justice has a new face, and it is perfectly symmetrical, with red hair,’ he said.

There followed a dance gala during which Jason brought his son Jake on stage. Then Jedidiah closed the event by introducing a last video that returned to his theme of saving the world through introspection. ‘You being you is changing everything,’ he said. ‘You guys are everything.’

The lights dimmed. Images of ethnically mixed young people appeared on screen. ‘There is only one vision, one life,’ intoned a voice-over. ‘It’s your turn to carry that torch, to realize you were born to ignite the world. You are worthy.’

Judging by what former LRA fighters had said in Obo, Joseph Kony was astonished by the international campaign to kill him. One of his former wives was Guinikpara Germaine, who had been abducted from Obo when she was 15 in March 2008 and had spent three years as one of his three ‘senior wives’. ‘He used to laugh and enjoy himself,’ she said. ‘But now he recognizes he is weak. He says everyone must fight to the end, even if they are all killed. When he thinks about what he wants and his ambitions, he’s like a man on drugs. He stays in his room and watches DVDs.’

I wondered whether Kony’s depression had lasted. At the time the villagers of Obo expected him to meet an imminent and spectacular Hollywood end, in a drone strike, perhaps, or a helicopter raid. But by early 2015, three years later, the US team had yet to confront the LRA leader. And if US commitment to killing Kony depended on the hype Invisible Children mustered, that, too, was fading. The group never again matched Kony 2012 for attention. Traffic to their website slowed and all but dried up. In the last days of 2014, the group announced it was folding.

If Kony remained at large, Invisible Children’s main legacy would be telling thousands of American college kids that they could change the world if they only looked into themselves hard enough. That message did seem to have struck a chord. In November 2013, when a UN force routed a group of eastern Congolese rebels called the M23, another California-based group called Falling Whistles achieved new heights of narcissism when it announced on its website: ‘We Stopped M23!!!!!!!!!!!!’ Under the slogan ‘Be a whistle-blower for peace,’ Falling Whistles sold tin and brass whistles over the web for $38–$58. For another $25, it would mail out a magazine called Free World Reader, ‘built to be bravely displayed on coffee tables and bookshelves around the world’. It had been this–selling tin whistles and arranging magazines on coffee tables–that had stopped Congo’s war.

At night in Obo, Dominic and I would watch the villagers dance and sing around giant wooden xylophones and congas. One new composition went:

The Americans are here

Our saviours are here

Our hope is here

Let’s dance.

One night we noticed one of the drummers wearing something familiar, a 2008 Obama campaign shirt bearing the slogan ‘Change You Can Believe In’. The people of Obo did believe. But I worried they would be disappointed. When humanitarians in Africa used the word ‘change’, I’d noticed, they’d mostly been talking about themselves.