SEVEN

SOUTH AFRICA

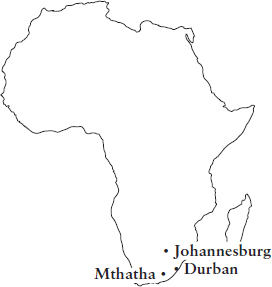

Durban was an African Miami, a city of beaches and apartment blocks painted in bubble-gum pastels where the summer never ended and the surf was always up. Way back from the strip, past the Victorian bungalows, past the low-rent estates, past the warehouses and the truck depots, up into the townships that were scattered like litter across the green foothills of the Zulu uplands, the world’s most legendary freedom movement was fighting a new war. Fighting, and dying. Between 2010 and 2012, South Africa’s police said 15 ANC members had been killed in the city. They were lying. A leaked internal ANC document put the true figure at 38. A Durban University crime researcher put the total at 40. That meant a comrade was being gunned down in Durban at least every month, mostly, according to the newspapers, by other comrades. What was happening to the ANC?

In a crowded coffee shop at the end of one of Durban’s piers, Sifiso sat down with his back to the water. Large, tall, with dreadlocks, Sifiso was a former aide to Sbu Sibiya, who had been the ANC’s provincial leader in Kwazulu-Natal until he was assassinated in July 2011.

A friend in the police had let Sifiso see the files on his former boss’s murder. Sifiso said the evidence suggested Sbu’s killers did not care if they were seen. All day a lookout had sat in the crowded waiting room outside Sbu’s office in the ANC’s Durban headquarters. In a suburb across town, a hitman had sat in the shade of a hedge outside Sbu’s house, cradling a 9mm pistol.

At 8.30 p.m. Sbu left work. The killers’ phone logs showed the lookout alerted his partner across town. There were a further 18 calls between the two. An hour later Sbu pulled into his driveway and waited for his electric security gate to open. The gunman walked up to the driver’s window and shot Sbu in the shoulder, then behind the ear, then in the heart. Sbu slumped over the wheel. His foot jammed on the accelerator. The car surged forward and rammed his garage wall, collapsing the building on top of it. The assassin fled, briefly calling the lookout once more. Then both men phoned several senior leaders in the Durban ANC.

‘Sbu had five kids,’ said Sifiso. ‘And his wife has no work.’

We sat in silence. It was a bright, clear day. The seagulls were wheeling on the wind and out on the water a flotilla of dinghies was racing. After a while, Sifiso said: ‘The police know who they are. I know who they are.’ He took a long drink of Coke. ‘I still have to work with some of them.’

Sifiso shook his head. ‘Sbu was my brother,’ he said. ‘He was everything to me. He always said, “If I die for the ANC, it’s OK. Even if I die, the ANC will live.”’

Sifiso wasn’t sure his friend was right. Sbu hadn’t been killed for a grand cause. The modern ANC had no ideology, he said. Anyone could join. The wrong people had. ‘It becomes no longer about changing the lives of the poor or building a society that is equal. People join because the ANC has state power and access to resources.’

One time, said Sifiso, Sbu had found five billion Rand missing from state finances. At others he discovered tenders that were awarded to friends, or paid twice for the same job, or for nothing. The legend of the ANC once made it seem immortal. Now corruption was killing everything it had stood for. Sbu had exposed the rot. ‘So they removed him,’ said Sifiso. ‘They killed him.’

The Archbishop and Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu lived a few miles from me in Cape Town. Tutu liked to tell a parable about the most corrosive legacy of apartheid: self-doubt. In the 1970s, he had obtained rare permission from the South African authorities to visit Africa’s most populous nation, Nigeria. For weeks, he swept around the country, marvelling at the cacophony of black freedom all around him. African politicians! African businessmen! African engineers! African doctors! One day he boarded an internal flight and felt his pride surge when he saw two African pilots in the cockpit. After the plane took off, however, it hit turbulence and Tutu was seized with panic. ‘I thought that was it,’ he said. ‘I thought: “Those blacks at the controls are going to crash!”’

Sbu’s death provoked the same awkward reaction in Sifiso. ‘People, even our own people, have begun to think a black man cannot lead,’ he said. Sifiso was acknowledging the heartbreak of Africa’s post-colonial years: how so many African independence movements had won the war only to mess up the peace.

One of the most striking contradictions about African liberation movements’ assumption of power was how inequality often grew back to levels as obscene as anything experienced under colonialism. By 2011, seven out of 10 of the most iniquitous countries in the world were African. Fourth on that list, after the Seychelles, the Comoros Islands and Namibia, was South Africa. There inequality had worsened significantly after it had been a legal requirement of a white supremacist state. European visitors often expressed shock at the persistence of white racism in post-apartheid South Africa, but the truth was that the decades after apartheid were a golden time to be a racist. Told you so, Ian Smith, architect of white Rhodesia, would crow to journalists visiting him at his retirement home next to Rhodes’ old beach cottage in Cape Town.

Smith believed the ANC’s sorry record in office revealed its political immaturity and racial inferiority. Sifiso thought there was a problem with the freedom fight itself. Freedom fighters fought the law. Under an oppressive state, breaking the law was freedom. It was freeing your mind and snatching back your authority. And if you were breaking the law, why not work with the experts? In its fight with apartheid, the ANC, and its Durban branch in particular, had worked in close alliance with black organized crime.

The problems began once the Struggle was over. Once they were the law, many of Africa’s freedom fighters saw no reason to stop breaking it. It was who they were, after all: free thinkers and revolutionaries, righteously radical entrepreneurs who took what they wanted and, in that act, found their liberation. It was a mindset well suited to rebellion. But it made for horrible rulers. Once in power, numerous ANC revolutionaries who had fought to better themselves made sure they did, helping themselves to state finances, often in alliance with their old criminal friends. With power so lucrative and used so unscrupulously, comrades were soon killing each other over housing deals or government contracts or simply because they thought it was their turn.

This was the paradox of liberation and democracy, said Sifiso. The ANC may have fought for democracy. But to do so effectively, it had had to become profoundly undemocratic. The Struggle had required discipline, hierarchy and a willingness to safeguard the movement above all else. When it took power in 1994, the ANC should have adjusted. ‘But we did not,’ said Sifiso. ‘We did not deliver to the people. We continued to deliver only to ourselves.’

Before he became South Africa’s fourth black President, Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma lived in a villa on a street not far from Nelson Mandela’s home in central Johannesburg lined with purple-flowered jacaranda trees. It was a time when most South Africans assumed Zuma’s misconduct had effectively barred him from government office. Zuma was from Durban and had once been head of the ANC’s intelligence wing. In that role he had forged the links with organized crime that helped the ANC smuggle weapons and people in and out of South Africa. Zuma maintained his contacts after apartheid ended. In 2005, one of them was jailed for 15 years for soliciting for Zuma a total of 783 bribes amounting to $400,000 over 10 years. As a result, Zuma himself was due to stand trial on four counts of corruption, one of racketeering, one of money-laundering and 12 of fraud.

Zuma’s reputation had already been tarnished by another trial, for rape. Though he was acquitted, his testimony that he washed off AIDS in a shower had scandalized South Africa’s liberals, who noted it was precisely that sort of ignorance that had given South Africa the world’s largest HIV/AIDS population. Nor were such concerns assuaged when the trial revealed the extent of Zuma’s polygamy–three wives, two fiancées and 17 children–or by his contention that by marrying some of his girlfriends (the list later grew to five wives) he was being socially responsible.

President Thabo Mbeki had sacked Zuma as his deputy in government. But it was the ANC rank and file, not the party president, who decided party positions and they had retained Zuma as the party’s No. 2, giving him a platform from which to fight back against Mbeki. Zuma was popular with the party. His earthiness contrasted well with the aloofness of Mbeki, who had spent 30 years in pipe-smoking British academia and spoke beautifully about being African but never once looked comfortable in Africa. Zuma was also highly motivated. Losing to Mbeki meant, very probably, going to jail. The young militant ANC leader, Julius Malema, then a close Zuma ally, said Zuma’s showdown with Mbeki ‘was very personal… informed by the fear of being arrested and going to prison. In that situation, you fight because you have nothing to lose.’

Zuma’s very private inspiration weighed against his ability to unite South Africans in the manner of Mandela. Mandela reached out across the country’s many divides. Zuma stuck to his supporters, whom he saw as an army, paid by patronage, with which he could fight his persecutors, be they Mbeki, the newspapers, whites or anyone else. His was not a subtle campaign. A halting and awkward public speaker who had not finished three years of school, Zuma largely confined his public appearances to singing the Zulu war anthem ‘Umshini Wam’, which translates loosely as ‘Bring Me My Machine Gun’.

Foreign dignitaries often described Zuma as a warm man at ease in his own skin. But when he appeared for his interview–tall, broad and bald in a white shirt, cream trousers and Polaroid glasses–I wondered whether they had been merely reaching for something positive to say. Zuma was distant and guarded. When I asked what he stood for, he was evasive. When I raised racism in South Africa, he interpreted my question as a racist affront. ‘You are asking me about race?’ he asked. When I asked if he would run for President, he said I didn’t understand. ‘I cannot run. The system that we follow, it’s never running.’ The ANC was not an open society, said Zuma, but an exclusive members-only organization whose inner circle decided who was to be deployed as President. ‘And I have never refused a deployment by the ANC.’

Zuma’s intent was to describe himself as a humble party servant. But his account of how South Africa’s next President would be chosen not by popular vote but appointed by the closed club of the ANC’s top ranks went to the heart of its post-apartheid quandary.

The legend of Mandela and the Struggle had given the party such a lock on power that it rendered the democracy which it inaugurated all but meaningless. At the ballot box, voters’ disappointment at the ANC in power was consistently trumped by their loyalty to its legend. The ANC’s vote had never dipped below 60 per cent.

And since the ANC wasn’t made to care, it didn’t. Its performance was dire. Though the government had stopped releasing many of the more damaging statistics, most independent research put unemployment at around 40 per cent, the HIV/AIDS population at five million, a rate of 10 per cent, and violent crime, at 45 murders a day, among the worst in the world.

In many ways, little had changed since apartheid. For most whites, the post-apartheid years had been an unqualified boon. More money, less guilt. For blacks, out of a total population of 50 million, 8.7 million still earned $1.25 or less a day. Most continued to live in the same township shacks, travelled inside the same crowded minibuses and, if they had jobs, worked in the same white-owned homes and businesses as they had before the revolution.

Most of the lives truly transformed by the ANC’s victory were those of the party’s own leaders. Many ANC councillors and ministers built empires of patronage and self-enrichment. The biggest single corruption case occurred in 1999 when overpayment in a $3.6 billion arms deal saw billions of dollars sprinkled across the ANC’s upper echelons. Only one ANC leader was ever held to account. Many seemed to view the public purse as their own private bank account. Counting spending on luxuries and privileges by ministers and their wives between 2009 and 2012, the opposition Democratic Alliance said the total had reached $550 million. It took exceptional brazenness to stand out in this orgy of graft, but those that managed to included a state security minister’s wife who was convicted of running an international drug ring and a local government minister caught using public money to fly first-class to Switzerland to visit his girlfriend, also in prison for narcotics.

That set the tone for the party’s lower ranks. Every national, provincial and local tender for every road, school and social housing project was a new opportunity. By 2012, South Africa’s anti-corruption police, the Special Investigating Unit, reckoned that up to a quarter of annual state spending on goods and services–$3.8 billion–was being wasted through overpayment and graft. The independent Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution added that a fifth of South Africa’s annual GDP–a towering $81.6 billion–was being lost to corruption and crime. The Auditor General said a third of all government departments had awarded contracts to companies owned by officials or their families. In one ANC-ruled province, the Eastern Cape, three-quarters of all contracts benefited officials in this way. The criminality, and the violence that went with it, climaxed in Zuma’s home state, Kwazulu-Natal, and its capital, Durban. KZN accounted for 1,103 of the 1,640 cases on the Auditor General’s desk.

Even at these lower levels, few party members were punished for their crimes. As long ago as 1996, Zuma made clear he considered the ANC above the law and ‘more important’ than the constitution. His assertion reflected how the party had set about ensuring that the state served it instead of the people. Penalties for corruption either evaporated entirely or were so diluted by parole and medical discharges that they became meaningless. Few corruption cases had as high a profile as that of Zuma’s advisor, but even he was released after serving just 28 months of his 15 years.

Nor were the police much better. In Durban in 2011, all 30 members of an elite organized crime unit were suspended, accused of more than 116 offences, including theft, racketeering and 28 murders, many of them contract hits ordered by politicians. Twenty-seven were later convicted of various offences. As in politics, the corruption went to the top. Two of South Africa’s post-apartheid national police chiefs were sacked for corruption. One, Jackie Selebi, who also happened to be head of Interpol at the time, was jailed for 15 years in August 2010 for taking bribes from a notorious mob boss and drug smuggler. Selebi was released on health grounds after serving just 229 days.

In theory, wayward ANC members might still have faced censure from the party’s own ruling body, the National Executive Committee. In practice, its membership made that unlikely. In December 2007, when it elected Zuma the party’s president, seven of its 80 members had been convicted of offences such as corruption, drink-driving and kidnapping; seven more were being investigated by police for offences including fraud and culpable homicide; three had faced internal ANC censorship for an array of scandals; and another eight were accused of a variety of further improprieties. Some of the cases were pursued, but most were quietly dropped.

One drawback of such impunity for rank-and-file ANC members with ambitions to rise up the party was the way it encouraged their superiors to hold onto their positions for as long as possible. With little turnover of personnel, they had no way to join this orgy of self-enrichment.

No way, perhaps, except killing the incumbent.

For anyone wanting to lead the ANC, the way forward was to buy enough supporters. Likewise, the best leader for corrupt ANC members was one who was as interested as they were in making government office pay. The risk of a leader’s exposure made him less likely to want to expose others.

As I left Zuma’s house, his press advisor pulled me aside and cautioned me against giving too much weight to the scandals surrounding Zuma. His support among ANC members was the only thing that mattered, she said, and that was rock-solid. She opened a hardback accountant’s book listing all the ANC branches and regional organizations in the country and started counting them off. ‘Kwazulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Eastern Cape… we’ve already got them,’ she said. ‘We’ve already got enough.’

‘Got them?’ I asked.

She closed her book and smiled. ‘It’s a done deal,’ she said.

It was. I saw Zuma again in May 2009, 18 months after he deposed Mbeki as president of the ANC and a month after the ANC’s fourth election landslide made him South Africa’s President. Perhaps because he felt untouchable, Zuma was more candid about the ANC’s failings. ‘There has been weakness in implementation,’ Zuma said. ‘After 15 years, people are saying: where is the delivery? We are aware of our shortcomings. These challenges are based in reality.’

It was unusual for an ANC leader to admit to any mistakes. I asked Zuma if that’s how he would describe them. ‘That’s the reality,’ said Zuma. ‘You lose nothing by admitting where there have been weaknesses.’ Still, in reality Zuma was being modest. By 2009 barely a week was passing without a new protest about state failure to provide water or roads or books or houses. The corruption scandals were continuing to pile up. Desmond Tutu, who had fought apartheid peacefully alongside the ANC’s guerrilla war, was calling the regime built by his former comrades ‘worse than apartheid’. The way Zuma portrayed it, however, the party was the unwitting victim of its own popularity. ‘After a decade or so in power, the success of liberation begins to challenge you,’ he said. ‘We are too strong. Such support and power can intoxicate the party and lead you into believing that you know it all. The situation tests your clarity, your understanding.’ Many other African liberation movements had failed the same test, he said. The ANC had come to the same point ‘where we might turn into something else’.

That wouldn’t happen, said Zuma, because he had a plan to restore the ANC’s moral authority. His government would record such a spectacular performance that all doubts would be erased. He would create 11 million jobs, he promised, build two universities and several railway lines, deploy an extra 1.3 million health workers and install five million solar heaters. The truth was that in power the ANC ‘might have fallen’ but, through determination and results, it would regain its stature.

It’s possible that Zuma may even have been sincere. He made similar promises a few months later to the South African parliament. But he kept none of them. What actions Zuma did take in power suggested that the preoccupations of patronage and protecting his position quickly became overwhelming.

As party president, he flung open the gates of the ANC in a recruitment drive among his supporters in Durban and Kwazulu-Natal that doubled membership from 600,000 to 1.2 million and gave the party a marked pro-Zuma character. As national President, he neutered the criminal justice system by appointing close allies as his ministers of justice, police and state security. (It was the state security minister whose wife was later convicted of drug-smuggling. The police minister was also soon exposed as a beneficiary of a government slush fund.) Zuma dismantled the Scorpions, the elite police unit which had pursued him for corruption. He appointed an unqualified ally as chief national prosecutor. He replaced the head of the supposedly independent Special Investigating Unit with a close advisor.

Those critics that he could not replace, silence or buy off, Zuma attacked. He sued journalists and cartoonists who questioned him and his supporters even demanded an artist destroy a portrait of him showing his penis (a comment on his polygamy, according to the artist). The ANC-led parliament then passed a law that allowed the state to jail for up to 25 years journalists and whistle-blowers who divulged state secrets. Precisely what defined a state secret would be up to the government to decide.

In 2012, an investigation by the opposition Democratic Alliance claimed Zuma and his family had cost the taxpayer close to $100 million in the previous five years, much of it spent on flights and private homes and $10 million in ‘spousal support’ going to Zuma’s wives. In November 2013, the Public Prosecutor found that the state had also spent $20 million on upgrades to Zuma’s sprawling private home at Nkandla, north of Durban, including 79 additional buildings, a pool and a cattle kraal.

None of it shook the ANC’s hold on power. In May 2014, despite a wide consensus that he should probably be in jail, the party reappointed Jacob Zuma for a second term as South Africa’s President.

ANC politicians confronting the difficulties of the present tended to reach back to the black-and-white certainties of the past. There the ANC was for ever the party of glorious and righteous revolution, the party of Nelson Mandela that freed South Africa and inspired the world. It was this past party that was still winning the present one its crushing election majorities.

This electoral trump card made the ANC fond of anniversaries and the biggest was 18 July, Mandela’s birthday. It was as good an occasion as any to visit Qunu, the small village where Mandela was raised and now lived again, a few hours south-west of Durban, on a bluff overlooking the rolling prairies of South Africa’s Eastern Cape.

Under apartheid, the Eastern Cape was where South Africa’s racial engineers had created two autonomous black homelands, the ‘Bantustans’ of Transkei and Ciskei. The disingenuous injustice of that marginalization, making a pale mockery of black freedom by confining it to two small half-states of chilly, thin-soiled and treeless hills, fuelled a wave of righteous rebellion from which many black leaders emerged: Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter and Albertina Sisulu, Chris Hani, Govan and Thabo Mbeki, and Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko.

Despite the region’s ties to the ANC, two decades after the party took power life in the Eastern Cape remained as desperate as ever. The statistics described true deprivation: the HIV/AIDS rate was 33 per cent; unemployment was 70 per cent; 78.3 per cent of the population had no running water; 88 per cent of people were below the poverty line; 93.3 per cent had no sewers, prompting intermittent outbreaks of cholera; and murder was three times the national average. The rape rate, that prime integer of social collapse, was jaw-dropping. In 2008, surveys of the rural Eastern Cape found 26.7 per cent of men admitted to being rapists. Of the victims, close to half were under 16, nearly a quarter under 11 and 9.4 per cent under six.

The morning of Mandela’s 94th birthday I drove into Mthatha, the regional centre. I’d visited two years before and found every lamp post plastered with flyers advertising the mobile phone numbers of surgeons offering same-day back-street abortions. Parents were keeping their children out of school for fear they would be raped as they walked to class. Two years on, the place hadn’t improved. At one set of traffic lights, a young beggar with filthy clothes and a dirty face knocked on my window, distracting me so his two companions could open a rear door and rifle my bag. At another junction, a boy of perhaps 14 stood in the road, stared at me through unseeing red eyes and urinated through his hands onto his ripped trousers and bare feet. When I pulled over to ask for directions to Laura Mpahlwa’s house, a woman said she would take me and got in. ‘You shouldn’t be out here alone,’ she said. ‘Tsotsis [gangsters] are everywhere.’

I’d arranged to meet Laura because I wanted to hear how life had changed for Mandela’s home-town contemporaries. Laura was born in Johannesburg in 1929. She was among the first to move to Soweto when it was designed as a black dormitory town under apartheid in 1948. Mandela’s struggle had taken him from Qunu to Johannesburg then Soweto but Laura had gone the other way, moving to Mthatha to work as a nurse in 1953.

With Transkei’s government little more than an apartheid puppet, the revolution was as fierce in Mthatha as Soweto. Laura’s first son spent five years on Robben Island for subversion, her second fled into exile, her third was tortured and Laura herself helped ANC leaders move in and out of South Africa. Living in the Eastern Cape was a daily reminder of what they were all fighting for. ‘Back then, it was mud huts all the way to Durban,’ said the 83-year-old.

Laura remembered how the mood in Transkei was transformed when apartheid collapsed. ‘People got lights,’ she said. ‘Some got water. Work started on roads. There were social grants.’ Still, when the ANC asked Laura to become an MP in the new parliament, she declined. ‘I was scared,’ she said. ‘Deep down I knew in my heart it was too big a position. I wasn’t trained for it. I wouldn’t cope.’

Other ANC members did not share her humility. Soon, the new ANC government was performing as poorly as she had feared. In the Eastern Cape, it still left its people short of what they needed–books, teachers, medicine, roads, houses, jobs–and failed to protect them from what they didn’t. ‘Drugs, high rates of teenage pregnancies and HIV/AIDS,’ said Laura. ‘There was mismanagement, misuse and, very disappointingly, a lot of fraud.’

Two of the few white people Laura knew in Mthatha were an American Episcopalian missionary couple, Jennie and Chris McConnachie. Chris was a surgeon and set about building Transkei’s only orthopaedic hospital. Jennie established a clinic in a squatter camp in the city whose Xhosa name, Itipini, meaning ‘In the Dumps’, described it physically and spiritually. When work on Chris’s hospital finished in 1996, Mandela himself came to open it. In his speech, the President said: ‘Nowhere has the legacy of apartheid been more shocking than in the state of health care in the former Transkei region.’ He described the hospital as ‘the difference between life and death’ for the people of the Eastern Cape. The new hospital, created ‘against all odds’ by an inspiring spirit of ‘partnership which has come to characterize our young democracy’, was an example of how a united South Africa would ‘build a better life for all’. Jennie showed me a cracked photograph of a smiling Chris with Mandela. ‘It was the proudest day of his life,’ she said.

Chris died in 2006. By then the hospital could run without him. The same could not be said of the rest of the Eastern Cape, however. Itipini, in many ways, was the lowest of the already very low. Shacks were built from scrap metal and cardboard. There was no sewerage, transport or power, and just two taps between 3,000 people. Unemployment was near-universal. As well as the clinic, Jennie’s mission ran a snack hall, a homework club, a soccer team, a recycling operation, a choir and a vegetable garden. She stayed on in Mthatha after Chris’s death because she was needed but also because, despite everything, Itipini was a community.

The rest of Mthatha took a different view. As a place of tiny alleyways and hidden corners, Itipini had a reputation for muggers and junkies. Years of simmering resentment exploded in April 2012 when a group of Itipini men murdered a liquor store owner in the neighbouring suburb of Waterfall. Two days later, the two communities held a meeting overseen by the police. Waterfall residents demanded Itipini be demolished. Several threatened to burn it down. Watched by police, they gave the Itipini residents one week to vacate.

A few nights later a group of Waterfall residents set fire to some shacks in Itipini. When the police arrived, they did not try to arrest the arsonists but instead beat and arrested the residents. Itipini’s families began moving out. A week after that the police returned with rifles and announced through a megaphone that all residents had to leave. They returned with bulldozers the next day. By evening, Itipini no longer existed.

The authorities, it turned out, had no plan for how to rehouse Itipini’s 3,000 people. Thousands wandered into Mthatha, seeking shelter from relatives or friends, hitching rides out of town or sleeping rough. A total of 268, including 24 children, moved into an empty Rotary Hall one and a half kilometres away, which the Waterfall residents immediately threatened to burn down as well. The authorities fed the Rotary group for two weeks, then stopped, complaining of the cost. Jennie had stepped in but was unsure how long she could continue. ‘How can I fundraise for a community that does not exist and a project that has been flattened?’ she asked.

Apartheid was built on an insistence that blacks were to be viewed not as individual human beings with rights and freedoms but collectively as an inferior class. The poverty of places like Transkei was taken as self-evident proof of black inadequacy. Blacks were backward, a race who couldn’t help themselves. And if whites and blacks were separated by mental ability and culture, it made sense to divide them by geography too. Blacks as a group were the problem. So blacks as a group were moved elsewhere.

It was that kind of thinking that had led Pretoria to demolish troublesome townships in white areas, such as the Johannesburg neighbourhood of Sophiatown, telling blacks to go back to the village. Twenty years after apartheid, Mthatha’s police were doing the same. Was Mthatha regressing towards apartheid? Had the ANC turned against freedom? Laura seemed to think so. ‘Look at this town now. Mthatha is more threatening now. You used to be able to walk around alone at night. Now you can’t talk to people, can’t even look at them or they’ll stab you and take whatever they want. It’s so sad. It wasn’t a better life for all.’

I drove to the Rotary Hall where some of Itipini’s survivors were gathered. Living there was another contemporary of Mandela, 78-year-old Thandeka Nani. With seven children and so many grandchildren she had lost count, Thandeka spent all day every day trying to find food. ‘It’s not the same as apartheid,’ she said, anticipating the question. ‘It’s worse.’

We were surrounded by about 20 men and women who were sitting on small piles of their belongings and listening to our conversation. When I asked Thandeka whether she had celebrated Mandela’s birthday, they angrily chorused: ‘No!’

Thandeka smiled, embarrassed by the younger generation’s directness. ‘We’re still waiting for our celebration,’ she said.

In the new South Africa, freedom had become indistinguishable from unrestrained criminality. The ruling party, the ANC, seemed to have particular difficulty telling them apart. Violence dominated much of the party’s language. Zuma sang ‘Bring Me My Machine Gun’. Julius Malema sang ‘Shoot the Boer’ and told supporters they should be prepared to kill for Zuma. When the metalworkers’ union broke off its support for the ANC, a party leader wrote on the Facebook page of the union’s boss, Irvin Jim: ‘We must deal with you to the extent of killing you. No apology.’ In Cape Town, the one South African province where the opposition Democratic Alliance held power, the ANC abandoned discussion in favour of flinging faeces at DA politicians, emptying buckets of the stuff over the steps of the provincial legislature and holding rallies which quickly degenerated into a smash-and-grab at street stalls in the city centre. Tutu was among 86 Capetonians who signed a public letter urging the ANC to wage its campaign of opposition ‘without resorting to violence, without fomenting hate’. In the provincial city of Pietermaritzburg I met a group of ANC members who had protested against the corruption of their own provincial leaders. Those leaders had promptly dispatched two assassins to shoot them. Both had been arrested, but a 42-year-old man called Phelele said the group’s luck couldn’t hold. ‘We expect to be killed,’ he said.

Some South Africans were learning from the ANC’s example. In the Eastern Cape, nurses protesting low pay kidnapped their managers and held them hostage as a negotiating tactic. Schoolchildren angry at the poor state of their school buildings burned them to the ground. There was a rash of murders on South Africa’s university campuses. And every few months the country’s townships would erupt in racist violence in which South Africans would lynch Somalis or Bangladeshis or Zimbabweans or Nigerians–whoever they accused of taking their jobs or being where they weren’t wanted. In the worst of these race riots in 2008 more than 60 people died. The police did little to stop the killing. When I looked into an anti-Somali mob lynching in Port Elizabeth in which one man had died, a white police captain told me: ‘Immigrants should expect a little difficulty from locals. Maybe they should weigh it up and if it really is that bad here, go back.’ Like their political masters, some police officers seemed to see violence as part of their job. Nine hundred prisoners died in police custody every year. In 2013 in Daveyton, east of Johannesburg, nine police officers were filmed dragging a 27-year-old Mozambican taxi driver down the road, his feet tied to the back of a police van.

Even South Africans were shocked, however, when on 16 August 2012 a squad of riot police gunned down 34 striking miners at a platinum mine at Marikana, north-west of Johannesburg. Miners’ strikes occupy a hallowed place in the legend of the Struggle. There were few injustices more evocative of apartheid than a black miner, digging into his ancestral land to enrich his white bosses while enduring low pay, lung disease, prison-like hostels and the occasional collapsing mine shaft. Under the leadership of the young head of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), Cyril Ramaphosa, miners’ strikes helped push the apartheid state towards collapse.

Come 2012, however, Ramaphosa was an ANC leader, a prospective successor to Zuma and one of the richest men in Africa, worth at least a billion dollars. Much of his wealth derived from his 9 per cent share in Lonmin, which operated the mine at Marikana. The 3,000 Marikana rock drillers armed with machetes, clubs and home-made pistols who had walked out were members of a new breakaway union that accused Ramaphosa’s old one of being in hock with the bosses. The strike quickly turned violent. Within days, eight people were dead. The strikers left the body of a suspected informant lying in the open, his head split open, his body arranged in a crucifix.

On 15 August 2012, Ramaphosa wrote an email to Lonmin’s chief commercial officer. ‘The terrible events that have unfolded cannot be described as a labour dispute,’ he said. ‘They are plainly dastardly criminal and must be characterized as such… there needs to be concomitant action to address this situation.’ The next day, the police began herding the miners into an area away from the mine. The miners pushed back. The police fired tear gas, rubber bullets, stun grenades and water cannon. When a group of miners charged, the police, who were being filmed by a number of television news crews, opened fire with automatic machine guns. More than a dozen protesters were killed. Off camera, the police pursued the miners into a rock gully where they executed at least 14 more at close range. The total number of dead and injured was 34 and 78 respectively. Many had been shot in the back.

The comparisons to apartheid were only compounded two weeks later when state prosecutors announced they would be using the apartheid-era law of incitement to charge 270 miners with 34 counts of murder and 78 counts of attempted murder. The state was saying the killings were the miners’ fault. They had murdered themselves.

The question people always asked about Zimbabwe was why Zimbabweans had not staged a second revolution against Mugabe. The same question haunted South Africa. There, too, the freedom that was meant to follow revolution had not materialized. What would it take for the people to rise up against the ANC?

One day, comparing the numbers of dead from South Africa’s crime with some of the tolls from Africa’s wars, I realized that maybe they already were. In its annual survey of global crime in 2013, the UN Office of Drugs and Crime reported South Africa had the highest murder rate in Africa and the sixth-highest in the world. At 16,250 murders a year, South African crime was around 10 times more deadly than the civil war in Somalia. South Africans couldn’t bring themselves, yet, to attack the ANC regime. But in their frustration and marginalization, they were waging war on each other.

It was hard to know where this new war began and the old struggle had ended. The beginning of the end of apartheid came in 1976 when Soweto, and then all South Africa’s townships, rose up in a tide of insurrection sparked by students refusing to learn Afrikaans. Forty years later large urban areas of South Africa remained no-go areas for the police. In his 2008 book Thin Blue, for which he spent 350 hours on patrol with South Africa’s police, the South African writer Jonny Steinberg described the relationship between the country’s police and its criminals as part ‘negotiated settlement’, part ‘tightly choreographed’ street theatre. Criminals, he observed, made a show of running away and officers half-heartedly pursued them. His thesis was that ‘the consent of citizens to be policed is a pre-condition of policing’ and in South Africa, for two generations, that consent had been lacking.

Other countries experienced violent crime as a temporary upsurge after a sudden shock, like a recession or the opening of a new drug route. In South Africa it had lasted for two generations–and that had shaped a nation. Unable to rely on the state, South Africans had learned to cope with crime on their own. Policing had become a private concern. In the townships there were hundreds of vigilante killings a year. More salubrious areas, like my own white-dominated neighbourhood, relied on South Africa’s 411,000 private security officers, whose number more than doubled that of policemen. Residents cocooned themselves in security estates. In the nineteenth century, South Africa’s Afrikaners had circled their wagons in an impenetrable laager when faced with attack. At the Battle of Blood River in 1838, 470 Afrikaners slaughtered more than 3,000 Zulus, at a cost of just three injured of their own. The security estate–walled-off clusters of houses protected by razor wire, electric fences, motion detectors and guards–was the twenty-first-century laager. Its purpose was the same: separation from danger, from the other.

What a racist regime once made mandatory, crime now made desirable. What prejudice had divided, inequality now atomized. In the first years after apartheid, Tutu had spoken about a Rainbow Nation. The new South Africa turned out to be no harmony of colour and, with its electric-fence partitions, barely even a nation. Freedom, in South Africa, was really a murderous free-for-all. The struggle against apartheid, rooted in black solidarity and an end to discrimination, had, in the end, led to fragmentation. South Africans lived apart and, ultimately, alone. And individuals couldn’t stop a country falling apart. From behind their barricades, they just got to watch.