NINE

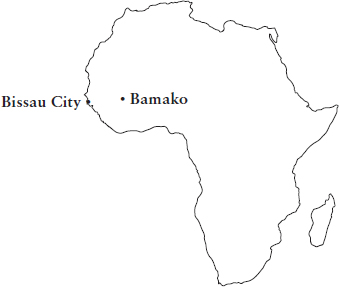

GUINEA-BISSAU AND MALI

In a small village on Africa’s western tip a 62-year-old woman stood outside her wooden, grass-roof hut and described how one night a plane landed on the road in front and unloaded several tons of South American cocaine.

It had been December 2011 and Quinta Balanta was taking the night air on her veranda at the edge of the village of Amedalae in the tiny country of Guinea-Bissau. Without warning, around 9.30 p.m. a group of 20 soldiers and 10 men in plain clothes arrived in a small convoy of pick-ups. Some of the soldiers set up a roadblock outside her house. The others took off down the road that leads out of Amedalae and ran dead straight for several kilometres across endless fields of flat, treeless rice paddies. Two and a half kilometres away, they set up another roadblock. Between the checkpoints, the soldiers unloaded hundreds of aluminium cooking bowls and placed them in parallel lines down each side of the road. Finally they filled the bowls with paraffin and lit them. ‘The light was amazing,’ said Quinta. ‘You’d have thought you were in Europe.’

Their preparations complete, the soldiers asked Quinta to go inside. ‘I refused. I said: “This is my house, something’s going on and I’m going to sit on my veranda and watch.” And at midnight I heard a plane coming from the sea. It went overhead, did a slow circle, turned back and started to land.’ The twin-prop touched down, taxied right up to Quinta’s house, then turned side-on. The pilot cut the engines and threw open the cargo door. Pulling up in two trucks, a few of the ground crew pumped fuel into the plane’s tanks while the rest unloaded the cargo. ‘The plane was full of big, white sacks–the kind you take to sell second-hand clothes at market,’ said Quinta. ‘They filled one truck, then another, then covered both trucks with tarpaulins.’

The entire operation, landing, refuelling and offloading perhaps two tons of cocaine, took 30 minutes. As soon as it was finished, the pilot started his engines, rumbled back down the road, took off and banked away to the west, towards the Atlantic. The soldiers and civilians left immediately as well, in the direction of a nearby farm owned by General Antonio Indjai, then head of Guinea-Bissau’s army.

There might have been a time, perhaps before dawn, when Bissau City hustled but I never saw it. There was never a breeze and the sun and humidity meant your shirt was scalding-wet across your back before you’d walked a block. The city subsisted in a state of exhausted collapse. Every wall was covered with black fungus and green moss and every pavement was buckled by the heat and shattered by decades of evening downpours.

The one benefit of this torpor was that Bissau City took no time at all to get to know. The need to move as little as possible meant everyone arranged themselves within a kilometre of each other in the city centre, around a handful of cafés and restaurants serving bottles of chilled water and vinho verde. I met a European honorary consul who greeted me on the first-floor balcony of a building that he used as his home, his office and a warehouse. ‘We’ve had so many coups,’ he said, stretching out a hand from his easy chair, ‘and apparently we’re going to have another one.’

It was September 2012. General Indjai had overthrown the government in April, the second coup in three years. Political calamity was followed by economic. The price of cashews had plummeted, and Bissau’s entire economy was tied up in 60 million tons of raw nuts that, since they could now only be sold for a loss, were rotting on the docks. ‘It’s like Saturday every day,’ said the honorary consul. ‘We don’t even bother opening in the afternoon.’

The depression only made the cars more incongruous. Parked in the broken road outside a neighbourhood restaurant a block from my hotel were a bright-yellow Hummer, a brand-new Range Rover, an Audi SUV and a Bentley–more than half a million dollars in cars all told. Inside, their owners included a bald Eastern European man talking on a satellite phone, his shirt open to show a gold medallion the size of a CD, and seven neatly bearded young Lebanese men silently sipping water. ‘Nobody even pretends any more,’ said the honorary consul. ‘It’s the only business in town.’ Diplomats estimated the amount of cocaine moving through Guinea-Bissau had doubled to 60 tons a year since Indjai’s coup. At that kind of volume, the trade was worth twice Guinea-Bissau’s official GDP.

At his offices in a side street just back from the centre, I met João Biague, the 44-year-old National Director of the Judicial Police and, as such, Guinea-Bissau’s lead anti-narcotics officer. João had no money to run an effective operation. One year the UN Office of Drugs and Crime had given his squad five cars but they had suspended their support after Indjai’s coup and, without it, the judicial police had no gas money. João did have about a dozen mobile phones and around 20 men, whom he deployed in the bars and cafés around town like the Kallista and Papa Loco’s. He also watched the cars. ‘I know how many Hummers there are in Guinea-Bissau,’ he said. ‘If I see them moving, I know something is happening.’

With no resources to stop the trade, João spent his time studying it. Cocaine, he discovered, had been transported across the Atlantic for thousands of years. In 1992, tests on several 3,000-year-old Egyptian mummies found traces of cocaine and nicotine, both of which originated in the Andes, suggesting not only that the transatlantic drug trade was several millennia old but that Egyptians or Africans crossed the ocean 2,500 years before Christopher Columbus. In the nineteenth century cocaine was used by doctors as an anaesthetic, prescribed by Sigmund Freud as a mood enhancer, dispensed to children as a treatment for toothache, mixed with wine in a blend given divine endorsement by Pope Leo XIII, used by the Antarctic explorers Ernest Shackleton and Captain Robert Scott and even included in the original recipe of Coca-Cola, which fused the drug with the kola nut. Southern American plantation and factory owners also used cocaine to improve the productivity of their black workers. By the early twentieth century that led to a string of stories in the New York Times about ‘Negro cocaine fiends’ who murdered and raped at will.

The backlash and cocaine’s prohibition in 1914 in the US suppressed its use for half a century. But in the late 1960s, Colombian growers began tapping a new American appetite for drugs. By the turn of the millennium the cartels discovered that their business growth in the US was flat-lining, not because of the US ‘war on drugs’ launched by President Richard Nixon in 1971, but simply because the market was saturated. It was then, said João, that the cartels realized the European market was still comparatively underdeveloped and that halfway to Europe, within range of small planes and fishing boats, were a series of eminently corruptible African countries with little in the way of law, government, air forces or navies.

In 2004 fishing trawlers, go-fast powerboats, small jets and cargo twin-props with custom-enlarged fuel tanks began shuttling across the Atlantic. ‘Highway 10’, so called because the route roughly followed the 10th parallel, was born. At the beginning of the decade, Europe’s cocaine market was a quarter of its American equivalent. By its end, the two markets matched each other at 350 tons a year. By 2014, there were 14–21 million cocaine users in the world, equating to one in 100 Westerners, rising to around three in 100 in Spain, the US and the UK. In Britain cocaine became as middle-class as Volvos or farmers’ markets.

The Africans rarely owned the drugs they were moving, something their Latin American, Middle Eastern and European bosses tended to reserve for themselves. But transporting was lucrative work and the syndicates quickly recruited customs officials, baggage handlers, soldiers, rebels, government ministers, diplomats, even a prime minister and president or two. The cocaine was flown in by small plane, then taken overland to another African country and flown out in the stomachs of human mules. It was shipped in by speedboat and freighted out again in a sea container stacked inside a pile of others. It was imported in the stomachs of African exchange students returning home from Brazil for the holidays, then re-exported hidden under tons of iced fish or even driven north across the Sahara in convoys of fat-tyred super-charged pick-ups.

To keep ahead of the law, the traffickers switched routes constantly, and quickly extended their reach across the continent. Soon every African country with a language in common with Latin America–Angola, the Azores, Cape Verde, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique–was a trafficking hub, as were all of Africa’s biggest airports–Nairobi, Lagos, Johannesburg and Cape Town. Among the airlines, Royal Air Maroc, which linked Brazil with North and West Africa and Europe, became a smugglers’ favourite, as did Africa’s biggest, South African Airways. In 2009, in the first of five cocaine busts on the airline in two years, an entire 15-person SAA crew was arrested at Heathrow accused of smuggling close to half a million dollars’ worth of the drug. One crew member was later jailed for seven years for trying to smuggle 3 kilograms of the drug in her underwear.

When it came to African countries, the cartels especially liked Guinea-Bissau. It had a coastline of a thousand hidden creeks and 88 islands, some with their own colonial-era airstrips. But with a population of 1.5 million and an average per capita income of $500, the country was too small and too poor to afford boats for its navy or planes for its air force.

When the traffickers first arrived around 2004, said João, ‘they called themselves businessmen. At first we didn’t understand because there was no business for them to do here.’ The first most people in Guinea-Bissau heard of cocaine was in 2005 when farmers on the coast found sacks of white powder washed up on the beach and, thinking it was fertilizer, sprinkled tens of millions of dollars of the drug on their crops. The plants died. But within a year, cocaine was a thriving mainstay of Guinea-Bissau’s economy. In December 2006, Dutch customs at Schiphol airport arrested 30 passengers on a single flight arriving from Bissau City, all on allegations of having swallowed several bags of cocaine.

Perhaps the biggest hindrance to João’s work was that as a state employee, ultimately he worked for Guinea-Bissau’s biggest cocaine smuggler, General Indjai. It was an isolating existence. João had had death threats and rarely slept in the same place twice. When I met him, he looked exhausted and told me he was on the point of quitting not just his job but his country, too. ‘Look, I don’t know about the future of the country,’ he said, ‘but I can tell you what I plan for my future. No country that has been through this has been able to fix it and if I cannot achieve what I want, there’s no need for me to stay.’ A few months later I heard he had quit and moved to Italy.

If Guinea-Bissau’s transition to a military-led narco-state was a tragedy for its people, the collapse of one of Africa’s smallest states had little strategic importance–even the US didn’t keep an embassy there. But as traffickers moved out across West Africa, so the criminality and instability they brought with them spread through the region. Between 2008 and 2013 West Africa saw six coups (two in Guinea-Bissau, and one each in Guinea-Conakry, Mali, Mauritania and Niger), two attempted coups (Gambia and Guinea-Conakry), two civil wars (Cote d’Ivoire and Mali), one popular revolution (Senegal) and a string of assassinations.

The scale of the drug-smuggling through Mali had been clear since 2 November 2009 when an ancient Boeing 727 was found burnt out in the middle of the desert near Tarkint in north-east Mali. Investigators from the UN Office of Drugs and Crime discovered that the smugglers flew the large Bissau-registered jet from Venezuela across the Atlantic to Mali. Touching down on a rocky desert strip, they unloaded perhaps 10 tons of cocaine, then, finding they had damaged the landing gear, torched the plane. Villagers around Tarkint said they’d seen other planes landing and taking off again for the best part of a year. The UNODC’s West Africa chief, Antonia Maria Costa, warned this new ‘larger, faster, more high-tech’ smuggling, plus the revelation that smugglers could afford to burn planes, showed that drug-trafficking in West Africa was attaining a ‘whole new dimension’.

The flag had been raised. Few chose to heed it. In Bamako in 2012 I couldn’t find a single diplomat who, beyond the bare facts of ‘Air Cocaine’, knew much about African drug-smuggling. ‘Nobody knows what the heck is flying over, or has any idea of what is coming in or coming out,’ was one American’s sunny summary. Cheikh Dioura, a Malian journalist who had written about cocaine for Reuters, told me he had had the same experience. Despite signs of an exploding trade in illegal drugs-smuggling to Europe, he said most diplomats were preoccupied with managing generous foreign aid programmes.

That reflected the story foreign donors preferred to tell about Mali. Before President Amadou Toumani Touré abruptly quit in April 2012, diplomats described Touré–known by his initials ‘ATT’–as an army officer who overthrew a dictator in 1991, then handed power to a democratically elected civilian president, then, 10 years later, legitimately won an election. It was an unusual narrative of democratic African leadership and Westerners loved it. Foreign aid rose to 50 per cent of the government’s budget under Touré. Aid workers held up Mali as an example to the continent. US Special Forces also conducted annual counter-terrorism training with the Malian army. ‘The country is considered one of the most politically and socially stable countries in Africa,’ read the World Bank’s 2007 assessment. ‘One of the most enlightened democracies in Africa,’ said USAID in 2012.

Cheikh Dioura, the Reuters stringer, had a different take on his former President. ‘Amadou Toumani Touré,’ he said, ‘was the biggest drug trafficker of all.’

Cheikh had a friend in the Malian secret service, a colonel who had been posted to Gao and Timbuktu and was covering the region when the ‘Air Cocaine’ plane was discovered in the desert. The colonel agreed to meet in an empty Chinese restaurant close to my hotel. A small man in scruffy plain clothes, the only clue to his identity was a neat military moustache. Cheikh warned me the colonel did not much like journalists and had even less time for ignorant foreigners. To open him up, Cheikh suggested I played up to the colonel’s predispositions.

I began by remarking that the stories I’d heard of the scale of trans-Sahara cocaine-trafficking seemed too wild to be true. The colonel snorted. ‘There are convoys every Friday!’ he said. The colonel described trans-Saharan processions of 15 to 22 cars that followed the old Tuareg caravan routes across the desert. In each cab was a driver and a fighter. As many as three convoys were moving at any one time. ‘Everyone knows this!’ exclaimed the colonel.

The colonel’s description tallied with that of a 32-year-old convoy driver Cheikh had taken me to meet in a dusty Bamako back street. The driver talked about taking three or four days to cross the Sahara. The trips were done in convoy, he said, guided by a Tuareg who knew the old routes from Mali and Niger into Algeria, Libya, Egypt, the Middle East and Europe. Like the colonel, the driver said half the cars in a typical convoy carried drugs and half provided security. Assuming a light load of half a ton per truck, and a minimal schedule of one convoy a month, that was still 48 tons of cocaine a year, worth around $1.8 billion in Europe.

Like Guinea-Bissau, the cocaine trade in northern Mali was more or less open. The driver said the man who ran it from Mali’s easternmost city of Gao was an Arab called Oumar. Oumar had gathered around him 100 young men in pimped-out 4x4s who liked to smoke hashish and tear around Gao in their cars. ‘The drivers are gone for a week,’ said the driver. ‘When they come back, they have big parties in the desert–girls, music, roasting sheep over big fires, spending money like water. Then they’re gone again.’ In an attempt to lower their profile, Oumar built 25 high-walled villas in a neighbourhood in Gao to house his drivers. The plan backfired. The townspeople of Gao immediately nicknamed the place Cocainebougou, or ‘Cocaine City’.

Especially worrying for Mali’s foreign aid donors was that Cheikh, the colonel and the driver all maintained that the smugglers were in business with government officials and Malian soldiers. ‘This is very well organized,’ Cheikh told me. ‘Mayors are involved. Police are involved. Politicians in Bamako are involved. There are links to security people and officials in Algeria and Niger and Morocco and Libya.’ When the colonel said something similar, I feigned shock. Surely he wasn’t suggesting corruption inside the Malian state? ‘Of course!’ bellowed the colonel. ‘There is very high complicity! There were times when we were prevented from going out on patrol. Our superiors told us not to go. I sent reports up the hierarchy asking: “What’s going on? Why are you preventing us from doing our work?” But I got nothing back.’

The driver said the corruption went to the very top. ‘Oumar called President Touré direct if he had any problems,’ he said. The colonel agreed. ‘It went all the way to Touré,’ he said. The colonel added, however, that he considered Mali’s former President something of an accidental drug baron. Mali’s Tuaregs, most of whom were extremely poor, had staged intermittent rebellions in the north throughout Mali’s 50-year history. Touré had tried to buy them off. He recruited Tuareg commanders into the army and gave them fat salaries and plenty of perks. After a Tuareg mutiny in 2006, Touré gave the Tuaregs even more, allowing them to run their territory as a highly corrupt, semi-autonomous state. The clan leaders diverted aid money intended for schools, roads and irrigation projects. They also took a cut from the cocaine trade.

Once the Malian state was sanctioning criminality, it wasn’t long before it was taking part in it. Hundreds of millions of dollars were kicked back to government officials and soldiers. As head of state Touré found himself, in effect, in business with drug smugglers–as did, by extension, the foreign donors who funded him. That was what Touré was referring to when, in a candid moment, he called Baba Ould Cheikh, the mayor of Tarkint later convicted of cocaine-smuggling, ‘mon bandit’. ‘Lots of people witnessed Baba Ould Cheikh talk to ATT on his Thuraya,’ said a second driver I met. ‘He called him “le grand patron”. If he had any problems with the police or security services, he would call ATT and say: “Your people are disturbing us. You need to speak to your men here and tell them to get out of our way.” Baba was Pablo Escobar.’ In 2012, the UN estimated West African smugglers either earned or helped launder around $500 million. Much of the money was spent on villa compounds like Cocainebougou that materialized along the smuggling route from Morocco to Mali and the building sites that suddenly spread across West Africa’s regional capital, Dakar in Senegal.

With corruption at the highest levels, Mali’s government became a business. Judges sold verdicts. MPs auctioned legislation. The rot destroyed the army’s command and control system. The colonel said that even if soldiers could properly identify their duty, they no longer had the means to perform it. ‘The Malian army has these old Chinese AKs from the 1960s,’ he complained. ‘They don’t even fire. There’s no food. The Malian army doesn’t have a map of northern Mali. War is knowledge and war takes money, and they know nothing and they have nothing.’

West Africa was rotten with drugs and corruption, wildly unstable, its governments were crazily unpopular and many of its Big Men were supported by big Western aid. Mali, especially, was all the proof anyone needed that Africa’s foreign humanitarians and its nationalist leaders were false prophets. The democracy held up by foreigners as an example to others was in reality a narco-state and its President, even if by default, a crime kingpin. It was perfect territory for bin Laden’s repurposed Islamic revolution. Al-Qaeda even had a branch in northern Mali, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

This was the context for the snowballing disaster that was to overtake Mali. That, and the fall of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in Libya. In the first decade of the new millennium, AQIM had made between $40 million and $65 million kidnapping and ransoming tourists in the Sahara. As tourist numbers predictably dwindled, the group switched to cocaine-smuggling, earning millions more dollars escorting the convoys of 4x4s across the Sahara. When Gaddafi was killed by a mob in October 2011, thousands of Gaddafi’s men, many of them ethnic Tuaregs from Mali and Niger, fled south into the Sahara. With them they took their weapons, including armoured vehicles, artillery, surface-to-air missiles, grenade launchers and thousands of Kalashnikovs. In Mali and Niger they met willing and flush buyers in AQIM.

In early 2012, a group of low-ranking officers in the Malian army staged a mutiny to protest about corruption in the upper ranks. To their surprise, Touré abruptly quit and flew to Senegal, tired, so diplomats said, of the endless squabbles inside his regime. The soldiers first denied they were taking over, then declared they were, after all. In the confusion, an alliance of northern Tuareg rebels and AQIM used their new firepower to overwhelm and rout the Malian army, seizing the entire north of Mali in just three days, including the cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal. A few months later, the Islamists turned on the Tuaregs and kicked them out of the country. Suddenly, in the middle of the Sahara about an hour’s flight south of Europe, there was a de facto al-Qaeda state the size of France.

The colonel predicted the Islamists would advance south towards Bamako within months. On 7 January 2013 convoys of AQIM fighters duly moved out of Timbuktu and, meeting no resistance, seemed to be heading for the capital. France had spent a fruitless year trying to marshal the creation of a West African intervention force to push back the Islamists. With Mali’s takeover by al-Qaeda imminent, Paris acted. French warplanes were bombing the Islamists within days.

On my return to Bamako, I found the diplomats and aid workers as clueless as before. ‘I don’t think anybody expected an Islamist offensive,’ said one. Now the advance had happened, however, the city was flooded with aid workers arriving to address an expected refugee emergency. In reality, there was none. A team from the International Medical Corps told me they were pulling out after two weeks of driving across Mali in which they found plenty of refugees but, since many northerners had gone to stay with relatives in the south, not a single one who needed help. Their assessment did nothing to deter a team of Oxfam press officers deployed to Bamako, who held a news conference declaring that 800,000 Malians needed ‘immediate food assistance’ and the world should send Oxfam as much money as possible.

All this seemingly wilful misreading of Mali left crucial questions unanswered. For one: what did the Islamists want? I found some answers from the first refugee I came across. Rama Koné was 32 and lodging at a relative’s house in Bamako. Rama had sold cigarettes on the streets of Konna, a small town of 5,000 about 12 hours north of Bamako. On the morning of 10 January, Rama was walking the main road through town when a convoy of 100 4x4s and pick-ups mounted with heavy machine guns and al-Qaeda’s black flags swept into town. Rama said he saw Malians and Arabs. The convoy drove to Konna’s police post and opened fire. The shooting last four hours. ‘At 2 p.m. the military ran and the Islamists went around town shouting, “Allah Akbar,”’ said Rama.

The Islamists then gathered around a man that Rama recognized instantly as Amadou Kouffa. ‘I have come here with a message for the people of Konna,’ Kouffa shouted, as the crowd gingerly stepped around the bodies of 50 Malian soldiers lying in the street. ‘There is no commandant for this town. There is no mayor. The government is not here today. From now on, all your issues are in the care of the imam of Konna.’ Gesturing to the south and the garrison town of Sévaré, 60 kilometres away, he added: ‘And, inshallah, on Friday I will pray in the mosque of Sévaré.’

I asked Rama how he knew Kouffa.

‘Everybody knew him,’ he replied. ‘He used to be a famous singer.’

The idea that the latest African jihad had been started by a former marabout was intriguing. Mali’s marabouts wandered from village to village reciting Islamic verses and performing folk music, precisely the kind of homespun departure from the Qur’an that a doctrinaire jihadi would consider heresy. What had driven an artist into the austerity of fundamentalism?

I drove north out of Bamako for central Mali. Kouffa came from a village near Konna that was also called Kouffa. In the regional capital Sévaré I tracked down one of his neighbours, a 35-year-old livestock trader called Niama Tutu. Niama said Kouffa had played the n’goni, the Malian guitar made from cord strung over a calabash covered with goatskin, and sang stories about the Prophet. Kouffa was a good storyteller and well respected. He also ran a small school. While his manner was ascetic and religious, it was also moderate. ‘His music was good and what he said was good,’ said Niama. ‘Everybody liked him.’

But as Kouffa entered his fifties, he began to change. His songs took on a political tone, decrying state corruption and brutality, especially the cocaine trade. One day in 2007 in Sévaré there was a conference of the Dawat-e-Islami, a conservative Islamic movement headquartered in Karachi, Pakistan. Kouffa attended and met its organizers to ask for their assistance in his campaign against the government. By this time, Kouffa’s popularity had grown to the point where he had a position in a Sévaré mosque. The Dawat, impressed with Kouffa’s following, agreed on condition that he give up the n’goni and instead begin preaching the Dawat’s far stricter version of Islam. They had a deal.

In time, Kouffa made trips to Dawat seminaries in Egypt and Tunisia. While in Mali, he was often accompanied on his travels by an Arab or Nigerian imam. But Kouffa took pains to show his new status had not gone to his head. He gave away the car the Dawat gave him, then two more, preferring to walk from village to village. His modesty contrasted well with the self-enrichment of the state, which remained the main target of his sermons. His followers soon numbered in the tens of thousands. Another friend, Oumar Fofo, 55, said Kouffa became a kind of Pied Piper figure. On his walks, he would often gather around 50 to 60 children whom he called Talibé– Taliban, or ‘students’.

Kouffa began proposing Islamic revolution as the only solution to the criminality of the Malian state. Only Islam could turn back the clock to a time before Western modernization opened the floodgates to greed and degeneracy. ‘Kouffa used to say that in the old days, before they had been led astray by all these modern things, men and women respected themselves,’ said Oumar. ‘He talked about corruption and the power the soldiers had taken from people. He would say: “I’m telling you this will all finish one day. Either you leave these things willingly, or you will be made to.”’

When AQIM and their Tuareg allies swept the north of Mali, Kouffa evidently decided that the day of salvation he had long predicted had finally arrived. He moved to Timbuktu and joined AQIM’s Islamic police.

For the West, the intricate and astonishing cause-and-effect of this disaster were damning. The same Malian government to which the West gave hundreds of millions of dollars and which the US was training in counter-terrorism had been business partners with an al-Qaeda group that kidnapped and ransomed Westerners and smuggled billions of dollars of cocaine to Europe. The Islamists had then used their earnings to buy Gaddafi’s guns and create a new terrorist state. ‘You know, this is not some small game,’ a Western diplomat in Guinea-Bissau had told me. ‘This is about financing terrorism on Europe’s southern border, about drug money from Guinea-Bissau and Mali being used for a bomb in London.’

But AQIM’s revolution was not the great liberation Kouffa had foreseen. Its Islamic police spent their days closing down Timbuktu’s tourist bars and nightclubs, forbidding women from leaving their homes and children from playing, stoning adulterers and smashing Timbuktu’s centuries-old Sufi tombs, some of which dated to the time of Mansa Musa. It was precisely the kind of alienating and authoritarian takeover that bin Laden had warned his followers against. Months later in Timbuktu, Associated Press found a six-part letter from Abdel-Malek Droukdel, AQIM’s leader, admonishing his men for their over-zealousness. ‘One of the wrong policies you carried out is the extreme speed with which you applied sharia, [which] will lead to people rejecting the religion, engender hatred towards the mujahedeen and lead to the failure of our experiment,’ wrote Droukdel. ‘Your officials need to control themselves. Like our Sheikh, Osama bin Laden, may he rest in peace, says in a previous letter, “States are not created from one night to the next.”’ The brothers should adopt more ‘mature and moderate rhetoric that reassures and calms’ and focus on local concerns. ‘Pretend to be a “domestic” movement,’ wrote Droukdel.

If their authoritarianism wasn’t bad enough, the Islamists were just as criminal as the Malian state. Shortly before I’d met the colonel in Bamako, I’d spoken to an Islamist leader who denied any involvement in trafficking. ‘As Muslims, we are the first to fight cocaine,’ he said. But his denial was undermined by scattered reports of Islamist fighters freely using cocaine. When I remarked to the colonel that it seemed unlikely that pious Islamists were involved, he thundered: ‘Have you even been listening to me at all?! It’s all done in the Islamists’ vehicles! The Islamists and the drug traffickers are the same!’ The colonel said the Islamist leader to whom I’d spoken was a small merchant from Timbuktu before he moved into cocaine. He became an Islamist as another commercial move, so he could continue his business after the Islamist takeover. It was good cover, said the colonel. ‘When the smugglers come to town,’ he said, ‘they come as Muslims with turbans, as preachers, and they slaughter sheep and say the money is from Saudi Arabia. They invite people to eat and pray with them and everyone is happy. That’s how they get people to support them. But it’s money from drugs! They’re traffickers!’

In the end, it was not the desire for a purifying revolution that had spurred Mali’s Islamists. It was the money they earned from trafficking cocaine and ransoming tourists. The Islamists’ involvement in crime was a perfect hypocrisy. By combining the self-righteousness of aid with the criminal despotism of Africa’s tyrants, they might have been purposely setting themselves up for failure. Sure enough, with no public support, their rebellion collapsed within days of France’s attack.

In the aftermath of the French assault, Kouffa’s fate was uncertain. Some reports said he fled overseas. Malian national radio announced his death. Another newspaper said he was wounded and captured, which likely also meant dead: as they retook territory, Malian soldiers routinely executed any Islamists they captured. Videos being passed around cell-phones in Sévaré showed the soldiers leaving a group of Islamists out in the desert to bake in the sun, their hands and knees tied behind their backs.

The state’s predatory brutality, which had fired Kouffa’s anger and inspired thousands to follow him, was back in force. The cocaine convoys soon resumed too. So did foreign aid, which grew to new heights in May 2013 when foreign donors pledged $4 billion to a new government led by a 78-year-old career politician. In Sévaré I had become friends with a travel agent who used to take tea with Kouffa. I was with him on the day state radio broadcast the new government line-up, filled with the same old faces. ‘Kouffa may have proposed the wrong solution,’ said the agent. ‘But he identified the right problems.’

One day in Sévaré my friend from Reuters, Cheikh Dioura, introduced me to a skinny man in his thirties with a small beard and scar above his left eye who went by the assumed name of Hayballa Ag Agali. Hayballa had been a cocaine convoy driver, then briefly joined the Islamists, and was now driving cocaine across the desert again. Hayballa said the war had only briefly disrupted the trade and there were now two main cocaine-smuggling groups in northern Mali, one dominated by Tuaregs and the other by Arabs. The Arab cartel was run, once again, by Oumar and Baba Ould Cheikh who, despite being arrested and jailed for cocaine-trafficking, was running his operation from his ‘jail’, a villa inside a Malian military compound in central Bamako.

Hayballa worked for the Tuareg group. He said that, if anything, cocaine-trafficking had become more organized since the French arrived. He described a smuggling route more than 1,000 kilometres long that ran between three desert relay stations across northern Mali, beginning near the Niger border in Mali’s far east and ending at the Algerian border in the far north. At each way station was a well-equipped logistics base containing generators, refrigerated food, underground storage tanks for water and fuel, cars, camouflage nets, even bulldozers to bury vehicles in the sand away from aerial surveillance and paint shops to paint the cars desert-yellow. ‘There’s everything at these places,’ said Hayballa. ‘If you are going for a job, they give you a car and a package, and you take it from one place to another. They give you a Thuraya and a GPS to track you. You go in convoy with maybe 50 other cars. The cars are all new, 4x4 pick-ups from Dubai, Toyota Land Cruisers mostly. When they have cocaine to move, the convoys run once or twice or week. Each car will take around half a ton. You arrive and a guy meets you. You don’t know him but he knows you because you have the Thuraya. They pay you $8,000 to $14,000. Sometimes they even give you the car too.’

On the road north to Sévaré, I had passed a two-kilometre-long French military convoy heading south. After nearly two years, by late 2014 the French were pulling out. But many Malians were left wondering what, precisely, the French intervention had achieved?

If the French had any doubts about the connection between cocaine-smuggling and the Tuareg and Islamist rebels, the smuggling camps dispelled that. One was run by a Tuareg commander, another by an AQIM lieutenant who had kidnapped and killed two French journalists in November 2013 and the third by a group of rogue Algerian generals and colonels who allowed AQIM a safe haven in the south of their country. Hayballa said hundreds of Islamist foot soldiers like him had also found work at the cocaine bases. But the French soldiers never once disturbed the traffickers. ‘They say it’s not part of their mission,’ said Hayballa.

For the French to see cocaine as unconnected to instability or Islamist militancy took an especially tight set of blinkers. The fluid identities of northern Mali meant the same individual could simultaneously be an Islamist, a Tuareg nationalist, a cocaine smuggler and a Malian official. Even peace talks had multiple meanings. ‘When you hear about a deal between the MNLA and some other group, it’s not a political thing, it’s two cartels doing a business deal,’ said Hayballa. ‘They just put a political hat on it.’

The French ignored these nuances and deceptions. They treated the Islamists and the Tuaregs as monolithic, exclusively political groups. Their plan was to replace the former with the latter. In effect, their intervention empowered the Tuareg cartels over the Islamist ones–though all the Islamist ones had to do was fly a Tuareg flag and the French would let them pass too. By allowing the cocaine business to thrive, the French were letting billions of illegal drugs continue on their way to Europe. They were also leaving in place the financial engine of all the armed groups in northern Mali, including the Islamists they had come to fight. That was allowing the smugglers to entrench themselves. To contrast themselves with the Malian state, they were even digging irrigation trenches and building schools and opening clinics. On my return to Bamako, I looked up the colonel. ‘They make out like they’re the real humanitarians,’ he said. ‘Like Pablo Escobar. If you’re out there in the desert, this, the big boss, the cartel, this is your state.’

Worst of all, by leaving the cocaine smugglers untouched, the French were fuelling the popular frustration at crime and corruption that had facilitated an Islamist revolution in the first place. The colonel asked me to imagine how a northern chief reacted on a visit to Bamako on which he saw aid money intended for the north disappearing instead into villa complexes and $100,000 cars. ‘The chief thinks: “This system cannot help my people. I’m going to fight this system.” So he buys a few cows to show them to foreigners as proof of their aid programme and the rest of the money he uses to buy guns and prepare for a revolution. Because one day he is going to stop this rotten system and the state behind it.’

Trouble seemed imminent. As the French pulled out, large unidentified desert convoys of hundreds of 4x4s had been spotted moving in behind them. Gao was in a state of panic, the town markets deserted and families locking themselves in their houses. UN peacekeepers were coming under attack from unidentified insurgents: eight had been killed. Suspected government informers were also turning up dead. ‘AQIM took five guys from Timbuktu and yesterday we found one of them strung from a tree in the desert outside the city,’ said the colonel. ‘They’d beheaded him.’ He felt another Islamic insurgency in Mali was inevitable. ‘Sooner or later it’s going to be the same thing all over again,’ he said.

One day in Bissau City I was having lunch with a friend when he answered his phone by saying: ‘Ah! My Taliban friend.’ I asked for an introduction and sure enough, Sheikh Mohamed Aziz arrived at my hotel room looking uncannily like an African Osama bin Laden. He was as tall as the former al-Qaeda leader, perhaps 6ft 4ins, and wore a white turban, a long grey bread, brown leather waistcoat and white robes, and carried a string of worry beads in his hand.

Guinea-Bissau was 50 per cent Muslim but inside that broad affiliation was considerable variation. In 1985, the Sheikh had converted to the same doctrinaire Saudi strand of Wahhabi Islam followed by bin Laden and other Sunni literalists. He had gone on to form the Youth Association for Social Integration, which proselytized to the young and built mosques, Qur’anic schools and health clinics with funding from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

The Sheikh was a loud, cheery man, quick to laugh and given to wide-eyed expressions. He said his association was experiencing terrific growth. He was building a new mosque and drawing thousands of new followers every month. The movement was popular, he said, because it tried to fill the gaps created when a ‘corrupt, selfish, thieving, lying’ government of cocaine smugglers fell short. ‘People’s frustrations are not addressed by the state,’ said the Sheikh. ‘So many say: “Let’s try an alternative.” And most of them choose Islam.’ Ultimately, the Sheikh’s movement promised its supporters freedom. ‘The only orders I obey come from the sky and the only one I trust is God. A man cannot be free if he doesn’t eat or he is sick or has no home. What I feel is complete independence, total freedom–and I share that with people.’

The Sheikh said it was part of his job to control the young men in his group. But he was candid about the direction in which it might be heading. ‘For sure, if our movement is increasing, it becomes a threat to whoever is in front of it,’ he said. Personally, he considered al-Qaeda to be fanatics who had perverted his faith and hadn’t fully thought through the consequences of their actions. ‘Jihad is a double-edged sword. You fight corruption. But your killing is another problem.’ But he conceded that his views were increasingly in the minority. ‘I tell them they have to be patient,’ said the Sheikh of his supporters. ‘Only if you have tried all other means can you use violence. But young people always want to solve problems with force.’

Whether or not the coming revolution was violent, the Sheikh was convinced it was imminent. ‘I’m optimistic,’ he said. ‘If one group oppresses others in their own interests, you can be sure that this group’s days are limited. The corruption is too much. The lies are too much. This selfishness is getting worse every day. All this can push people. Our organization is increasing. People are even afraid of us. These are good signs.’ The Sheikh whooped and clapped his hands at the prospect of West Africa’s next Islamist upheaval. ‘This time is victory time for Islam.’