TWELVE

ETHIOPIA, NIGERIA AND KENYA

‘This is Africa’s moment!’ exclaimed Eleni Gabri-Madhin. ‘This is catalytic! This affects millions!’

Eleni was sitting in a leather chair in her glass-walled office on the fourth floor of the Ethiopia Commodities Exchange in downtown Addis Ababa. She was wearing a black trouser suit and a gold necklace and earrings, and as she spoke she tucked her legs underneath her. I knew Eleni as a regular at Africa business conferences. For years, these events had had all the atmosphere of a palliative counselling session, with the experts confronting participants with the evidence of their condition, in this case depressing statistics on African poverty. But more recently they had become the forums for a different range of emotions: optimism, even giddiness and joy. In the excitement, few were pausing to ponder why Africa was taking off. Eleni’s speeches suggested she had pondered little else for most of her professional life.

As we shook hands and sat down, I remarked that Ethiopia might not be the first place people would imagine setting up a food commodity exchange. Eleni laughed and shook her head. ‘You’re right, people don’t understand,’ she said. ‘They ask, “Who is this crazy woman, creating a food exchange in a country where there isn’t any food?”’

Well, quite. How did she explain it?

By the dawn of the twentieth century, two of the great suppressors of Africa’s population had finally evaporated. Slavery had been abolished across all of Europe and the US. The late nineteenth century also saw the advent of modern medicine.

As a result, Africa’s population doubled from 120 million in 1900 to 229.8 million in 1950, then accelerated further to half a billion in 1980 and finally a full billion in 2009. Africa was filling its empty spaces. The old ways–wandering, common land, ubuntu– didn’t suit this increasingly crowded land. More appropriate was farming, private property and boundaries. This was the familiar path to development humankind had followed in other parts of the world. As individual rights replaced communal ones and capitalism overtook feudalism, this was how we had evolved a life based around individual freedom.

In the mid to late twentieth century, however, it became clear that Africa, once again, was breaking away from the norm. At independence, most of Africa was richer than most of Asia. But over the next four decades Asia soared while Africa slowed, stagnated and, in many places, shrank. By 2000, 11 African countries were poorer than they had been in 1960 and few Africans earned more than a few hundred dollars a year. In particular, African food production was not rising with population as it had in other parts of the world. Africans’ growing numbers seemed to be leading their continent not into a new era of prosperity but into Malthusian catastrophe. Millions starved to death in Biafra, Sudan, Somalia and Ethiopia. More than ever, Africa was a place of poverty, hunger, war, dictators and disaster. What was wrong with Africa?

Eleni was born in Ethiopia in 1965. At the time, the country was still a feudal kingdom ruled by an Emperor, Haile Selassie, who traced his line to Noah. Eleni’s family was connected to the old aristocratic order. That did not spare it from the turmoil of hunger. In 1974, the harvests failed and more than 300,000 Ethiopians died in a famine. Half-hearted efforts by Selassie to alleviate the suffering were the last straw for a group of young Communists inside an army long frustrated by the deference and archaic traditions of the imperial court.

But the Derg and their leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, did not inaugurate the liberation for which Ethiopians had hoped. Consumed by Cold War paranoia, and so suspicious of freedom that it even banned Ethiopians’ beloved jazz, the new regime executed 100,000 people. Hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians fled into exile. Eleni travelled with her mother and sister to Rwanda, where her father was working for the UN Development Programme. In reduced circumstances, it was in Rwanda that Eleni observed small-scale African farmers up close for the first time. ‘I saw this agriculture with no tools by people who were uneducated and living in grinding poverty,’ Eleni said. ‘It was clear to me that these farmers were stuck.’

By the mid 1980s, Eleni was studying at Cornell University in New York when a second Ethiopian famine changed her life again. Mengistu’s collectivist farms were failing, Ethiopia’s food production had plunged and in 1984–5 images of more starving Ethiopians began appearing on television. ‘I had this feeling of grieving,’ said Eleni. ‘And I remember my university had a tradition of kids’ food fights in the cafeteria after the meal. So one night I leaped out of my chair and I said: “Stop it! Stop doing this! People in my country are starving!” And of course they didn’t stop. In fact, I’m pretty sure they threw food at me. But for me that became a seminal moment. From then on, I was going to focus on this issue of how to end hunger.’

Overcoming hunger would rescue Ethiopia from starvation and the food aid dole. Eleni also understood from Ethiopia’s experience that hunger and dictatorship were connected. Despots were bad at caring for their people. And maybe, Eleni began to think, moving beyond famine was also a way of moving beyond autocrats.

A decade later, by which time Eleni was studying African grain markets for her Ph.D. at Stanford, she finally returned to Africa–and soon discovered something that surprised her. ‘Wherever I went in Africa,’ she said, ‘I kept seeing the same thing–people changing grain sacks. Each buyer and seller would check each and every bag, ton by ton, lorry by lorry. Then they would change the sacks. This would happen four to five times before the grain got to market. And there were millions of grain sacks in Africa.’ Why was transporting and trading food so laborious? Why all the changing of sacks? ‘Because there was no system of checking whether what you were buying was good stuff,’ said Eleni. ‘There was a high default rate. There was no transparency. Trading, basically, was high-risk. You had to be physically present.’ Eleni later calculated the cost of this mistrust, in time and effort wasted, was adding 26 per cent to Africa’s grain price.

When Eleni returned to Stanford, she told her professor about the sacks. ‘How do we solve this?’ she asked.

‘It’s called a commodity exchange,’ her tutor replied.

If an early stage in human progress is moving from foraging to farming, a secondary one is graduating from farming to survive to farming for profit–and in that simple act the farmer sows the seeds of all the economies of the world. The dynamics are simple. A commercial farmer aims to make a surplus to sell beyond his family’s immediate subsistence needs. When he takes his extra food to market, he connects to a commercial grid. When he trades his surplus, then returns again the next month, then invests the returns from these trips in better seed or fertilizer or a tractor so that he can produce an even bigger harvest next year, those are the beginnings of an economy.

These are the humble motivations that have guided humankind from cave to city. As Eleni suspected, as well as growing economic freedom, they contain the seeds of political liberty. By establishing an ability to live autonomously without the assistance or permission of higher authority, a man advances from living as a serf or an ubuntu foot soldier to what we would call a free man. Commercial farming was how we invented capitalism. And in the entrepreneurialism and self-reliance it required, the way it weakened the authority of others and strengthened our own, the way it brought people together and made them harder to push around, it was how the majority wrested their liberty from kings and chiefs and tyrants. Farming was freedom.

Human beings have also never found a better way to develop materially than farming. Studies by the International Food Policy Research Institute and the World Bank show that every 1 per cent rise in agricultural incomes reduces the number of people living in extreme poverty by 0.6–1.8 per cent. In Europe the transition from feudalism to the modern age was lengthy and contentious, running through several centuries of revolutions. In India and China it was faster and smoother. A ‘green revolution’ in India in the 1960s introduced more productive seeds and mechanization to farmers and moved the country from intermittent starvation to exporting $10 billion a year in food today. In China, from 1978 to 2011 farmers’ incomes grew 7 per cent a year, the number of farmers needed to feed a population of 1.3 billion fell from 380 million to 200 million and, partly as a result, Chinese poverty fell from 31 per cent to close to 2 per cent today.

In Africa, where seven out of every 10 people still live off the land, the implications of moving to commercial agriculture are profound. On a continent where poverty has left hundreds of millions powerless before aid, tyranny or terrorism, the causal link to freedom is little short of electric. This was not living subject to the funding fashions of aid workers or the caprice of despots. Nor was it, as the jihadis would have it, being sucked into yet another subservient relationship with the perfidious West. Farming for profit was how Africa might leave behind an existence subject to the whims of any of its bullies. This was how a billion Africans might climb out of the Rift.

The problem for Africa’s farmers, the reason they were ‘stuck’, in Eleni’s phrase, was that their transition from subsistence growers to businessmen was incomplete. A fully functional agricultural industry required at least some ingredients of modern agribusiness: available and affordable seeds and fertilizer, the latest farming methods, farming insurance, clear land rights, and infrastructure like roads, warehouses, mills, irrigation and refrigerators.

Historically, African farmers had none of these. Even in 2015, 96 per cent of African farms were still rain-fed and use of fertilizers and tractors in Africa was about 10 per cent of the world norm. Thanks to ubuntu and the nomadic life, property rights and land ownership were often unclear–even in 2015, title was established over just 10 per cent of farmland–making it difficult to buy or sell land, which in turn discouraged investment. As a result, African land was around half as productive as land in Asia or Latin America.

This was what Eleni’s tutor meant when he said Africa was missing a commodity exchange. Exchanges require a fully functional agricultural sector, everything Africa didn’t have. Eleni decided to look at the problem not as a disability but as a challenge. ‘Could a small, stagnant economy get all the pieces of a modern market together?’ she asked. In effect, she was asking: was Africa ready for its future?

In 2007 Eleni gave up a well-paid job at the World Bank to find out. She set up a central trading house, the ECX, and a countryside network of 55 refrigerated food warehouses. To end the obsessive sack-changing, she hired inspectors to guarantee integrity. They would check goods for quantity and quality, then certify both in receipts. So that every farmer would know he was getting a fair price, Eleni erected scores of electronic price boards at markets across Ethiopia and introduced a mobile phone service to transmit the latest crop prices by text message.

By building the physical infrastructure for commercial farming, Eleni was also laying the foundations for its financial framework. That was needed because farming was risky. The vagaries of weather meant even good farmers had bad years and without spreading the risk via insurance or loans, all farmers eventually went bust. That was why small, developing-world farmers often stuck to subsistence operations. To grow more was to risk more.

Eleni’s exchange allowed farmers to predict prices or even, via a futures market, guarantee them. And if farmers could accurately estimate future incomes, banks and insurance houses would share their risk. And if that happened, Ethiopia’s farmers would suddenly have a brand-new incentive: to grow as much food as possible.

Before I spoke to Eleni, I’d spent an hour on the trading floor beneath her office watching buyers and sellers trade commodities in 10-minute sessions and, in the short breaks in between, swap stories about cars, girls and big nights out. The conversation quickly turned to the exchange’s star trader, absent that day. ‘The guy came from nothing,’ the floor manager said, ‘and he just bought a hotel. He buys five, maybe six million dollars a session. He sets the price for African coffee by himself.’ I fell into conversation with a 38-year-old sesame trader. Takele Chemeda idolized Bill Gates and Gordon Gecko. He’d got his start in dried peas, then moved up to maize, then sesame, and said it wouldn’t be long before he hit the big league: coffee. Before he could tell me more the bell rang for a new session and Takele was off, striding into the pit, yelling: ‘I love this job! I love this money!’

In 1984–5, a million Ethiopians had starved to death. A generation later, Ethiopia’s first yuppies were food traders. In only its third year of operation, the ECX turned over a billion dollars in 12 months. This was another reason why, a month later, the Somali famine would feel so strange to me. The success of Eleni and the ECX traders suggested Africa’s future lay in feeding the world, rather than the other way round.

If Ethiopia’s growth was part of a continental change, I should be seeing innovations like ECX appearing across Africa. And I was seeing those. Across the continent rice production was growing 8.4 per cent a year, partly due to the use of more productive strains of rice and partly because more land was being farmed. Government biotechnology engineers in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania were experimenting with new types of disease-resistant banana and cottonseeds. Cote d’Ivoire was using a new type of cocoa plant that raised productivity three times. In Rwanda, the introduction of 116 basic washing stations catapulted the quality of the country’s coffee from among the worst in the world to among the best, quadrupling earnings for Rwanda’s three million coffee farmers. One of the world’s poorest countries, Malawi, transformed its economy by subsidizing fertilizer and better seeds from 2006. For three years afterwards, economic growth was 6.5 per cent.

The results were especially evident in Africa’s three cornerstone economies. In Kenya, hundreds of new kilometre-square poly-tunnel farms had sprung up along the floor of the Rift Valley from where farmers exported a total of $2.3 billion in vegetables and flowers in 2011, up 50 per cent in three years. South African farmers were sending lamb and ostrich, apples and oranges, wine and olives, even celeriac and quinces all over the world and had doubled their output to $6.3 billion in the same time. In Nigeria, in the five years to 2011, farmers tripled their exports to $1.8 billion and that figure was only expected to multiply: between 2011 and 2013 the government oversaw the investment of $8 billion in agriculture.

Foreigners used to the idea of feeding Africans sometimes had trouble with the notion that the reverse might be becoming true. But the proof was there on their food packaging. That fair-trade Cadbury’s chocolate bar? Cocoa grown in Cote d’Ivoire. Starbucks’ gourmet coffee? The Rwandan highlands. That out-of-season asparagus, those mange-tout peas and those oddly perfect midwinter roses? All from Mount Kenya. Quietly, in small print, those food labels were subverting the notion of Africa as a land of hunger.

Nigeria’s Minister of Agriculture, Akinwumi Adesina, was a particular cheerleader for the idea of Africa as an agricultural powerhouse. Only 60 per cent of Nigeria’s farmland was actually farmed, he noted, and only 10 per cent of it efficiently. What was needed was a change in attitude. ‘Agriculture is not a social sector,’ he declared. ‘Agriculture is a business.’

Historically, Africa’s great expanses had been too big for anyone to harness. Suddenly that was no longer the case. And with a total of 1.46 billion acres of unused arable land in Africa, compared to 741 million in Latin America and just 198 million in the rest of the world, Adesina’s vision of Africa feeding the world only seemed to make sense. Farming was also helping foster a new continental cohesion to underpin this new Africa. Just as building the ECX required Eleni to create a national infrastructure, other initiatives to modernize farming did the same for Africa. Co-operatives sprang up such as the East Africa Dairy Development in Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda, which organized 179,000 farmers into collectives, giving them access to credit, insurance, refrigeration and veterinarians with the aim of doubling their incomes in five years. African banks, which had ignored farmers for decades, were suddenly tripping over themselves to offer loans and insurance. The boom in food production drove the formation of four African free-trade blocs–the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and East African Common market (EAC)–the last three of which merged with each other in 2015 in the 26-nation Tripartite Free Trade Area that, echoing Rhodes, finally did run from Cape Town to Cairo. Common currencies in southern and eastern Africa, matching the one already in circulation in West Africa, were one likely result.

Farms, roads and markets; banks, exchanges and insurance; the uniting of individual farmers in businesses, co-operatives and trade federations–these were the building blocks of a connected, integrated twenty-first-century continent. No longer did Africa’s wealth depend on the luck and skill of the hunter, whether an African with a spear or a foreigner with a drill. Now it was about a maturing and broadening economy. From 2000–8 natural resources like oil, diamonds and gold only accounted for a quarter of Africa’s growth. After living for so long in the past, Africans were stepping into the future.

Eleni and I talked about much of this. I told her my theory about Africa’s size being key to understanding it and how all that land seemed to make the most perfect reversal possible: from a continent of hunger to a land of food. Eleni replied that she’d spent her professional life trying to incite exactly that kind of continental Big Bang. So I was not surprised a few months later when I learned that she had left ECX to found a new company whose ambition was setting up exchanges across Africa.

Before we said goodbye, she told me that what was driving her wasn’t so much the commercial logic of commodity exchanges or the financial rewards of running them but seeing the way they changed lives. She told me a story to show me what she meant. ‘At ECX, we used to tell each other to be patient, that things don’t change fast,’ she said. ‘And then there was this beautiful day in a village in northern Ethiopia when we convinced a food co-operative that instead of going to the old market, and haggling, changing sacks, maybe waiting weeks for payment and after all that probably being ripped off, they should put 200 sacks of grain in our system as an experiment.

‘So the farmers brought their grain in on a tractor. They were given a warehouse receipt and told it would be sold the next day. The following morning, we had hundreds of these farmers lined up outside the bank to see whether their money would be there at 11 a.m., as we’d promised it would.

‘And at precisely 11 a.m., they sent a man in. He walks in. And a little while later, he walks out. In his hand, he’s got the balance of the co-operative’s account on a piece of paper. And he holds it in the air, and he shouts: “It’s there! It’s all there!”

‘And the crowd erupted. People were crying. People were laughing. The women were ululating. It was amazing. Just amazing.’

Eleni let the scene sit between us for a moment. Then she laughed, leaned forward and tapped me on the knee. ‘This idea of yours about Africa being big,’ she said. ‘Imagine how big this will be!’

I once met a blind man who liked to walk clean across Lagos and said he was considering buying a car since he saw as well as 80 per cent of Lagos’ drivers. It was a good joke and, like most good jokes, it held a truth. As with Africa’s farmers, many of Africa’s city dwellers seemed stuck–in traffic, in dead-end casual labour jobs, in sprawling ghetto townships. Africa’s cities were less motors for advancement than stagnant poverty traps. Nobody seemed to know a way out. Like the blind man, everyone was just feeling their way around.

Lagos was the prime example of this anarchic inertia. It was the biggest city in the world’s poorest continent and one of its fastest-growing: the population was expected to be as much as 25 million by 2015. When I first visited in 2009, Lagos represented a concentration of poor people unmatched anywhere on earth. Around 65 per cent of Lagosians–13 million people–lived below the poverty line, earning $2 or less a day. This was chaos at its ugliest, deadliest and most colossal, a malarial megalopolis built of driftwood and tin, with little running water, electricity, jobs or law and order, where the ground was filled with garbage, the water with sewage and the air with the smog from a million unmuffled exhausts. Lagos was one of the world’s first failing city states, a victim of what UN-Habitat, the agency for human settlement, calls over-urbanization, a concentration of too many people with too little money in too little space.

Farming was crucial to Africa’s progress, especially in rural countries like Ethiopia. But with ever more Africans moving to cities, urban progress was becoming just as important. Nigeria was slightly smaller than Ethiopia but, at 160 million, had twice the population. In that sense, Lagos was a vision of Africa’s future. And before city governor Babatunde Fashola took over in 2007, it was not a pretty one. ‘If you have 20 million people, you are going to need more water, more roads, more jetties, more schools, more hospitals, more space for housing,’ said Fashola in his city-centre office. ‘And all of that literally stopped for about 30 years.’ Lagos was a place, he said, ‘of broken promises and very evident despair’.

Governor Fashola was not a conventional Nigerian politician. Rather than barge his way across town with sirens blaring and lights flashing, he chose to endure Lagos’ traffic with his fellow citizens. Fashola also read economic theory for fun. On his bedside table: books by economists who saw potential in poverty, like the Indian C.K. Prahalad or the Peruvian Hernando de Soto. These poor-world academics argued that the underprivileged might lack money as individuals but together, in their billions, they represented a mighty untapped resource. This vision matched Fashola’s own. When he looked around the city, he said, ‘In everything I see, I see opportunity. The infrastructural deficit of Lagos [is also] a chance to relieve its poverty. If there is a bad road, it means we need an engineer and labourers, architects, valuers, land merchants, banks, merchandisers, suppliers of iron rods and cement, and food courts.’

Once elected governor, Fashola set about implementing his vision. His idea was simple and remarkable: take one of the world’s worst cities and make it one of the best. He embarked on a comprehensive overhaul of Lagos’ infrastructure, building new expressways, widening and resurfacing others, stringing street lights along all the main highways, integrating road with rail, air and even water.

The city was too big to transform overnight, but improvements were soon marked. Traffic slackened, garbage dumps were replaced with green parks, the proportion of Lagosians with access to clean water rose from a third to two-thirds in three years and flood defences covering 10.8 million people were strengthened. By the by, the amount of work generated by reconditioning such a vast city created tens of thousands of government jobs, 42,000 in waste and environmental management alone. New state skills centres trained a further 250,000 people in new trades, then offered them microloans to set up their own businesses.

The centrepiece of this new city was Eko Atlantic, an entirely new district being built from scratch out of the ocean by using sand dredged up from the ocean floor. It would be six and a half kilometres wide, extend one and a half kilometres out into the ocean and house 250,000 residents with offices for 150,000 commuters. A model at the offices of its developers featured gin-clear canals, giant malls, three marinas, trams, the island’s own power station and a sail-shaped 55-storey skyscraper that would be the new headquarters for a Nigerian bank. ‘It will be orderly development, linked transport–rail, water taxis and roads–improved law and order, a place to call home, a place to live and work and spend your leisure time, where things work, where there is electricity, water, health,’ said Fashola. ‘That’s what I see: it will still be an African city state operating to global standards.’ Lagos was to be the remade face of a new continent. An African Hong Kong. ‘It’s an amazing thing,’ said a World Bank official, ‘not least because it actually looks like it will happen.’

The purpose behind Lagos’ new infrastructure was to put the city’s teeming millions on a grid, just as Eleni’s commodity exchange had done for farmers. But this wasn’t just about roads and bridges and canals. Less tangible and more ambitious even than Eko Atlantic were Fashola’s plans for Lagos’ slums. To transform them, Fashola hired Hernando de Soto. De Soto’s work focused on the unregulated, unmapped and illegal businesses in which the vast majority of poor people work. As individuals, argued de Soto, these people had little that could be described as wealth. But viewed together, they were a huge, overlooked opportunity. How to unstick them? Property rights, said de Soto. ‘Since the Domesday Book, people have been linked to their assets and identified themselves through them. Property rights are the key to finding out how many citizens you’ve got, and who they are and what they’re doing. Once you have that, then you can reform the city.’

When de Soto’s team first went to work in Lagos in May 2009, they discovered the mother of all informal economies. Their survey revealed that 68 per cent of the city’s property and 94 per cent of its businesses, with assets worth a collective $45.1 billion, functioned outside the law and any kind of formal registration. That handily beat annual foreign aid to Nigeria ($11.4 billion) and dwarfed foreign investment ($5.4 billion).

To banish the old anarchy and create an inclusive and orderly city that would be the guiding spear to Nigeria’s future, Fashola had to pierce the murk, said de Soto. Rather than great, illegal slums where no one owned homes–and so could never leave or sell or rent them–he advocated giving residents property rights so they had the freedom to do all those things. Make the informal economy formal. End the free-for-all and the law of the jungle by legalizing, regulating and taxing. Squash suspicion and rumour. Create certainty. Rescue trust.

It seemed to be working. The city was coming together in a collective effort. ‘We set out to demonstrate we can transform ourselves if everybody joins,’ said Fashola. And they were. One result seemed to be a remarkable revival in community spirit. Armed robberies in Lagos fell 89 per cent one year and car theft and murder more than halved. The rising sense of citizenship revealed itself in another way. By 2010, the governor was raising 70 per cent of the state’s income from local taxes. The government was accountable to its people once again.

The implications of Lagos’ transformation were vast for a continent where two-thirds of city residents lived in slums. Fashola saw his task in almost spiritual terms. A city that did not function according to rules, said Fashola, ‘creates desperate conditions for people and reduces their ability to resist temptation’. The old Lagos left its people at the mercy of others. They became accomplices to criminals, victims for gangster politicians, beggars for aid workers and recruits for extremists. Fashola said the new Lagos offered its people a way to break free from all of them. ‘Corruption is a manifestation of frustration, a symptom of an economy that does not work. What we did was suggest in very practical terms–in ways that are touchable and can be seen–that things can be changed no matter how bad they are. We restored hope. We restored belief.’

Fashola was giving every Lagosian a documented stake in the city’s future. His success ensured his methods were copied, particularly by the governor of Nigeria’s second-largest city, Kano in the far north. But in other ways Kano felt as if it were in a different country. Built around a 1,000-year-old caravanserai where Africans and Arabs had met on the southern edge of the Sahara for 50 generations, it was a desert oasis of somewhere between four and 10 million people. In the old quarter, behind arched gateways whose stone entrances bore the marks of centuries of battle and wayward carts, was a market whose narrow alleys still attracted Tuareg nomads, Arab merchants and traders from as far away as China to buy spices, beads, jewels, kohl, armadillo skins, black-spotted serval coats and cotton dyed in Kano’s 500-year-old indigo pits.

Tradition ran deep in Kano. With thousands of northern notables, French photographer Benedicte Kurzen and I had been invited to a ‘turbaning’ at the Emir’s palace, where Kano’s 83-year-old monarch, Alhaji Ado Abdullahi Bayero, was due to ennoble five men. At the palace gates, stallions harnessed with ornate silver-studded faceplates and saddles stitched in yellow, red, green, black and gold leather stood ready to parade the new nobles around the city. The courtyard beyond was a vast, sweaty tapestry of thousands of men dressed in babban riga of 100 different colours: orange, gold, magenta, fawn, striped brown, sunburst-yellow, ochre, sky-blue, navy-blue, indigo and purple. Their turbans were lace, cotton and silk, flecked with black and gold. They wore embroidered leather slippers from Timbuktu, Mombasa and Peshawar.

In a small hall beyond, sitting on the floor against one wall, was a line of men in especially elaborate dress, the last of whom was barely visible beneath what looked like a giant black-silk puffball decorated with red and silver polka dots. His face was hidden, his eyes concealed behind sunglasses and his head and chin wrapped in a black, red and gold turban tied in an elaborate topknot that resembled the ears of a Playboy Bunny. The man underneath rose to his feet and removed his sunglasses. His face was neat and small and his hair close-cropped. ‘You made it!’ he exclaimed in Queen’s English. A hand was extended. ‘Lamido Sanusi.’ We shook hands and Lamido gestured at the crowd. ‘Quite the show, eh?’ he said. Then he addressed Benedicte in fluent French.

Nigeria’s great flaw was its politics of division. To its persistent divides of north-south, Christian-Muslim and rich-poor, its elite-focused economic growth had added a newer identity crisis: modern-ancient. But Lamido transcended the identities that trapped so many others. He was a Muslim royal, the heir apparent to the emirate of Kano, but as a boy he had attended a Catholic prep school. He had studied economics and worked for Citibank on Wall Street but also read Islamic law and Greek philosophy in Khartoum at a time when a fellow foreign resident of the city was Osama bin Laden. He was a scion of the Nigerian establishment, but for the past five years he had hounded that establishment for corruption in his job as Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria. ‘I removed bankers from their jobs, I fought the national assembly over their pay, I put a captain of industry in jail, I said half the civil service should be fired, I said the petroleum minister was leasing her own private planes to the government, paying herself every time she took a flight,’ he said. Finally, in September 2013, Lamido told President Goodluck Jonathan that around $20 billion was missing from Nigeria’s national oil accounts. When the allegation was leaked, Jonathan suspended him. ‘He took it personally,’ huffed Lamido.

Formally, Lamido was in the last three days of his five-year term as Central Bank Governor. But already he was contemplating a new role as a ‘public intellectual’, holding forth on issues such as state corruption and incompetence. ‘The government is full of sycophants, people who sit at the feet of the President and tell him the sun shines out of his back,’ he said. The normal functions of government, he added, had been almost completely abandoned. ‘We have people ready to be minister for eight years and achieve nothing. Even the President and Vice-President. Most of the politicians who get a job in government, they want the title, they want the salary and the privileges. They have no sense of shame. I used to ask them what is the power capacity of the country? What about national security? Health? Education? Culture? It drove them crazy.’

Days later, the ailing Emir died in his sleep, and Lamido was elevated to a post even better suited to goading the government. His accession made him king of one of the most influential fiefdoms in northern Nigeria. Though the position had no constitutional power, the high regard in which the Emir was held gave Lamido wide spiritual and moral authority. What was more, in contrast to his old job as Central Bank Governor, Lamido had no loyalty to the government and couldn’t be fired. He had, in effect, become chief government critic for life. ‘It’s a remarkable thing in Africa,’ Lamido mused. ‘Technically the traditional leaders are not in the constitution but they are somehow the true leaders. There is a sense that politicians are only temporary.’

The same suspicion hung over Nigeria itself. It was the continental heavyweight–by population, economy, oil reserves and with its possession of Africa’s largest city. And yet as it marked its 100th year, the big question was whether the government’s failure would become the nation’s. Was a government crippled by ineptitude and greed even capable of addressing the deprivation it had allowed in northern Nigeria and the ferocious rebellion that it had spawned? Would Nigeria fall apart? ‘A state fails when its leadership fails,’ said Lamido. ‘Personally I am not very optimistic. Our citizens are left on their own to perform the functions of the state. I think we have all the symptoms of a failing state.’

The notion that Nigeria might be disintegrating just as foreign-investor excitement over it was peaking was not easy to digest. But neither was a country in which a group of militants could kidnap a whole girls’ school and get clean away with it. I had been going to Nigeria for years, but I told Lamido I often left feeling as confused as when I arrived. He smiled. To understand Nigeria, he said, you had to accept you were entering a world where all truth was relative and all fact transient, and what seemed to be the most visceral and bloody reality could ultimately be revealed as artifice. ‘It’s about power,’ said Lamido. ‘Power, and the construction of truth.’

Lamido switched identities as easily as changing from a babban riga into a suit. To his mind, the solution to Nigeria’s problems was to recognize the divisive and binary thinking of identity politics as the fiction it was. ‘These identities are about a small elite that finds it useful to deliberately construct them, elevate them to the status of belief for their subjects and to take up positions around it,’ he said. Such an identity might be ‘forged around a sense of an exclusion’ or around ‘ethnicity or religion’ or simply around ‘a sense of opposition to “the other”’. Its purpose, always, was to accrue power. The British called it divide and rule. Their Nigerian successors called it politics. ‘If you are able to place yourself as the mouthpiece of some imaginary identity you have created, if you create a whole theory about how you have been excluded and marginalized, then that’s how politicians operate,’ said Lamido. ‘They make a blood sport of identity.’

Lamido rejected that. When he was fired as Central Bank Governor, he said, he could have made much out of how a southern president was getting rid of a northern leader. He refused, mainly because it would have offended one of his alternative identities: the economist. At its most fundamental, an economy is about working together. That co-operation spurs material progress. But it also implies political advances: individuals making choices and defining themselves, rather than being defined by others.

Most importantly, the way that an economy required and reinforced popular cohesion, and could shape a scattered and even segregated people into a mighty whole–that was a way to create a nation that was connected and capable and resilient. That was the kind of country where the people were masters of their leaders, not the other way round. In Lagos, Fashola said corruption was instigated by economic frustration. Lamido saw a thriving economy as the foundation of a liberating patriotic spirit. ‘You build a sense of loyalty to your country–of national identity–where people have a sense of belonging,’ he said. ‘And the best way of fostering belonging is providing economic opportunities. It’s only when an economy stalls that identity politics kicks in and becomes about the other, about these immigrants and that religion.’

In the end, said Lamido, economic development was about freedom. Nigeria’s best hope of moving past the prison of its politics, off the aid dole, and leaving behind the nightmare of Boko Haram lay in growing the economy and transforming it from an apparatus of exclusion into one of inclusion.

Before he was forced out of the Central Bank, Lamido had unveiled a project which had the potential to do just that: a biometric database for the entire Nigerian economy, the first of its kind in the world. After registering their fingerprints, Nigerians would be able to withdraw cash from ATMs or pay for goods at checkouts, gas stations or shops simply by presenting their finger to an electronic reader.

The system would be almost impossible to defraud. Businesses would also be able to see if their customers had a history of bad credit or crime. Should the database be rolled out across Nigeria, the room for forgery, fraud, bribery and money-laundering would shrink dramatically. Cash, especially suitcases of it, would become automatically suspect. Most significantly, with an indelible imprint at the heart of Nigerian life, the database would finally give Nigerians what they had lacked since the great colonial lie of Nigeria was first promulgated: their own immutable and individual identity. This was how Nigerians could move past fearful and centrifugal tribal hate to a future of secure and confident citizenry. It was the grid that would connect every Nigerian to the nation and, at a stroke, diminish their politicians’ monopoly on power.

Like Fashola, Lamido saw the database in almost mystical terms: as an attempt to light up the dark mysteries of money and power in Nigeria with facts, figures and records. ‘It closes off opportunities for opacity and brings more clarity,’ he said. ‘It will be revolutionary.’

It was the most hopeful I’d heard Lamido be. His optimism was tempered by doubts over whether the database could be mothballed or his other reforms undone. He also saw no sign that the Nigerian state was climbing out of its hole of venality. ‘The state just does what it wants, perpetuating itself in power using its monopoly on money and the army,’ said Lamido. ‘It’s Louis XIV. L’état, c’est moi. Effectively, it’s a monarchy.’

Lamido added that the number of people he knew who had met ‘mysterious ends’ suggested the Nigerian state would always try to destroy its critics. Still, he would not be cowed. And whether he was there to see it or not, he was sure liberty would win. As a student, he said, the Stoics taught him that ‘even if I am jailed or killed, I am not going to lose. If you think of loss as the loss of freedom or loss of life, you miss the point. If you die for a just cause, you are free. They are the ones who are dead, lost, finished.’ Whether you were an emir, a militant or the parent of a lost Chibok girl, Lamido was saying that freedom was defined only by the limits of your imagination. Nigeria’s leaders had none. Even if they won, even if they killed him, they would never be free. ‘What they think is important,’ said Lamido, ‘is not.’

It was possible Denis Karema had too much imagination. It poured out of him in a flood, and he often had trouble putting it into words. When I asked what his company did, he said: ‘We create next-generation real-time anti-fraud solutions for near field communicators.’

Denis was sitting sideways on a bench, stirring sugar into a latte on the wooden table between us. We were on the open-air terrace outside a branch of Java House, Nairobi’s own Starbucks. Behind us was one of Nairobi’s handful of modern malls, the Junction, whose tenants included the Phoenicia Lebanese + Sushi Bar, Planet Yoghurt, an Apple iStore and a six-screen cinema. On the other side was a large car park full of new-looking European and Asian sedans.

Denis was 30, tall and had a neat moustache. He had arrived with an equally tall, younger-looking American called Connor McCarthy, who was on sabbatical from his management consultancy and had taken it upon himself to chaperone Denis. Not that Denis needed much minding. When Connor announced that there was ‘a ton of opportunity’ in Denis’ company Usalama (meaning ‘safety’ in Swahili) and that he was considering an investment of ‘10 kay to 100 kay’, Denis shot back: ‘200 kay’.

‘Well, maybe 200 kay,’ Connor conceded.

Denis’ expression suggested that, even for 200 kay, Connor would be getting a steal. Usalama, explained Denis, would revolutionize the fight against electronic fraud. ‘As money becomes easier to transfer, it becomes easier to compromise,’ he said. ‘If you look at the amounts lost to electronic fraud, Deloitte’s says it’s $4.8 billion a year but we think that that’s 10 per cent of the true total.’ Denis gave me a look that said: ‘QED’.

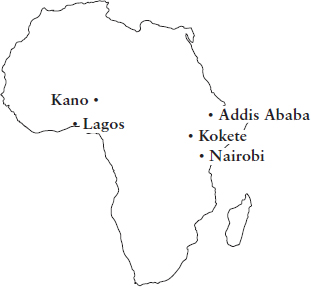

In Addis, Eleni had showed me how Africa might move out of the past. In Lagos, Fashola had demonstrated how a city might win back its present, and in Kano Lamido had done the same for a country. I was hoping that Denis might give me some idea of what came next. But he was skipping too far ahead. I told Denis he would have to slow down and go back. He looked disappointed but sighed, gathered himself and, speaking slowly and checking that I was keeping pace with my notes, he began.

Denis told me he was born in September 1983 in the tea gardens on the southern slopes of Mount Kenya, close to the provincial market town of Murang’a, about an hour north of Nairobi. Famine was gathering pace in Ethiopia a few hundred kilometres to the north and Denis’ early life was tough, though not in a way that a Live Aid audience would recognize. His parents were modestly paid provincial civil servants and they split up when Denis was seven. His mother Eunice raised him and his younger brother alone. Asked to describe life for three on a single government salary, Denis replied: ‘Challenging.’

But difficulty only seemed to spur Denis on. ‘I always knew I was bigger than my town,’ he said. At 13, he persuaded his grandfather to pay for him to attend one of Africa’s most prestigious schools, Maseno, near Kisumu on the shores of Lake Victoria in western Kenya. Maseno’s students had included several future ministers, a number of African freedom fighters and Barack Obama Snr, economist and father of the first black US President.

But if it was history and prestige that attracted Denis to Maseno, it was a new gadget then arriving in Kenya that obsessed him while he was there. The year Denis started his studies, 1997, was the year the first mobile phones came to Africa. At the time, mobiles were new anywhere in the world. Denis remembers his mother visiting one weekend and showing him the first he had ever seen: a bulky German model with a green screen, an aerial and a hand-strap to assist with the device’s considerable weight. Denis couldn’t get over its tininess. ‘Compared to a call box,’ he clarified. ‘I was amazed.’

The following year Denis bought a second-hand phone of his own, an early Nokia. Initially calls on Kenya’s first mobile provider, Safaricom, were extortionate, ‘so I learned how to communicate all my stories in seconds’. Denis also began to notice how his nerdiness–an addiction to chess and Pac-Man that, until then, had closeted him in geeky isolation–now transformed him into something else: cool. Or as Denis rather nerdily put it: ‘The phone improved my social ratings.’

In the West and the Far East the arrival of the mobile phone was greeted with equal parts enthusiasm and annoyance. The convenience was undeniable, but people fretted about noise pollution, brain tumours and a decline in manners. Still, it soon became fashionable to talk about how the world was shrinking to a global village.

For a far larger proportion of the planet, mobiles were experienced as something that promised precisely the opposite. Where the world had once ended at the village limits, now it exploded beyond them–to the town, the port, the capital, even across borders and continents and oceans. Mobiles connected to anywhere and, with the advent of cheap prepaid pricing, to anyone. The effect on Africa was transformative. Overnight, Africa’s great silent spaces began to shrink. Africans who previously had never used a light bulb or sent a letter or ridden in a private car found they could suddenly dial into our common existence. For the first time in history, it was possible not only to talk about all humanity, but talk to it too. ‘Technology gave me access,’ said Denis. ‘The kind of access I could not have had without actually travelling to Europe or America.’

Unsurprisingly, demand for such an astounding innovation was unprecedented, all the more because Africa’s rising population meant the continent now represented the second-largest mobile market in the world. In 15 years, Africans went from possessing a few million landlines to one billion mobiles at the end of 2015.

The knock-on effect on economic growth was as dramatic as the invention of farming. A series of studies by, variously, the London Business School, the World Bank and the consultants Deloitte found that for every extra one in 10 Africans who possessed a mobile, their country’s national income rose by 0.6 per cent–1.2 per cent. Why? Because progress is a collective effort. The special significance of the mobile to Africa was that, uniquely, it let Africans leapfrog the kind of heavy infrastructure that Africa’s size had long made all but impossible. Mobiles–off-grid and able to operate remotely–conquered Africa’s empty spaces in an instant. They tamed Africa’s girth not by trussing it up in girders and wires but by effortlessly superseding it. Air-time did what land-line never could.

Such a stunning invention was hardly going to remain limited to calling home. Soon the mobile became the basis of a whole new African infrastructure. Mobile education–classes and lectures recorded remotely then delivered by website, email or text message–meant students no longer had to walk for hours to school and could even access teaching where none had previously existed. Mobile health services allowed patients to consult a doctor, learn about a disease’s symptoms and prevention, even perform first aid–all without visiting a surgery or hospital and often for free. Because seven out of 10 Africans were farmers, hundreds of the most popular African apps related to agriculture: meat and vegetable prices were sent out by text message, as were reliable predictors of rain, sun and crop disease. A Kenyan app called iCow alerted herders to the vagaries of their beasts’ oestrous cycle.

In the West, mobile and internet services formed a virtual grid which ran alongside the old, physical one and whose biggest selling point was convenience: online shopping or bill payment or email, an instant electronic postal service to replace letters. In Africa, the mobile installed a grid where none had previously existed. This was not expediency. This was plugging in, opening up and shouting out for the first time. This was what Africa’s size had prevented for all human history. It was liberation.

The mobile also had a profound impact on perceptions of Africa. In his seminal The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, C.K. Prahalad wrote in a similar vein to de Soto about how most businesses were missing a huge pot of money by assuming the poor had none. Actually, said Prahalad, they did have a little. What’s more, there were billions of them. For the right goods and services –cheap, mass-market–they represented the world’s biggest consumer market.

Mobiles proved Prahalad was right. If Africans didn’t have phones–or pens or lights or shampoo or even much of a varied diet–it wasn’t because of lack of demand but lack of supply. The key for a business wishing to unlock this vast and virgin territory was to adjust its view of Africans. No longer were they to be seen as penniless charity cases. Mobiles weren’t pushed out of the back of a plane to the starving millions. They were bought, in shops, by millions of ordinary African consumers. What’s more, it was becoming evident that there were enough of those to usher in a global financial revolution.

At Maseno, Denis saw mobiles take off. Instinctively, he understood the commercial promise of Prahalad’s billions. ‘In my heart, I had a feeling–which I still have even now–that tech is better than discovering oil,’ he said.

Denis spent his last few years at school learning how to write computer programs. In 2005, he was accepted to study computer science at Kenyatta University in Nairobi. He began earning money almost immediately, and fell for technology all over again. ‘I loved the way offering a little IT consultation would generate instant cash for me,’ he said.

He wasn’t the only one. Nairobi is East Africa’s business hub and the headquarters for banks, insurers, manufacturers, food exporters and a large tourism industry. In the early twenty-first century, it desperately needed the skills Denis and a new generation of teenage African code writers could offer. For Africa’s geeks, it was the perfect start-up environment. ‘Money was never an issue,’ said Denis. ‘If I needed $1,000, I just developed a couple of websites and sold them.’

The young programmers shared a pioneering, hippy-ish spirit. As Denis described it, ‘there was any number of people running start-ups. We’d meet and exchange information on where to get funding so that everyone had enough to build their own product. You looked out for other entrepreneurs. It wasn’t a competition. They could access my methods and I could access theirs. The idea was for all of us to get the opportunities–and that would be good for all our businesses here.’ In an article I wrote at the time, I drew parallels to the California tech explosion a generation before and gave its Kenyan equivalent a nickname that stuck: Silicon Savannah.

In 2008, his fourth and final year at Kenyatta University, Denis began to focus on his first big solo project. Taking data from police forces across Kenya, he developed Kenya’s inaugural national missing persons database. His room-mate, meanwhile, built mzoori.com, an online market designed specifically for Kenyan shoppers, whose preference for examining what they were buying, and the seller too–like Eleni’s grain traders–mitigated against the success of a site like Amazon. The idea of mzoori.com was to match buyers with sellers for a small fee. The site quickly became one of the biggest in Kenya. Looking back, Denis said he felt he and his classmates were at the forefront of a revolution. ‘We thought technology could really change everything,’ he said, ‘the way we run businesses and institutions, the speed, the value, the transparency.’

Revolutionaries find it hard to stay out of politics. And an industry of people in their twenties, which valued entrepreneurs and collaborators and change, naturally had a pronounced anti-establishment edge. Denis got a particular kick out of befuddling Kenya’s bureaucrats. ‘They didn’t understand what we were talking about,’ said Denis. ‘I’d say: “It’s a development system to find missing people.” And they’d say: “Oh. So it’s a system. OK. Right.” Then there’d be this long pause. Then they’d ask, “Is it something we can hold?”’

There was a more serious political edge to Silicon Savannah. On his weekends, Denis would return home to Murang’a to teach basic computer skills to his former classmates, some of whom he described as brilliant but plain unlucky victims of inequality. Among his most celebrated peers were four programmers who, in response to months of tribal violence after a disputed election in 2008, built the crowd-mapping platform ushahidi (‘witness’ in Swahili), designed to take information of attacks sent in by text, email, instant message or phone calls and plot it on a map of the country. One of the ushahidi four, Erik Hersman, went on to found iHub, a workspace in downtown Nairobi that became a base for 100 Silicon Savannah start-ups. iHub subscribed to two explicitly political goals. To build Africa’s name as a source of tech talent. And to use technology to promote political freedom.

Surprisingly, perhaps, these were ambitions shared by Bitange Ndemo, the Kenyan civil servant in charge of technology. In July 2011, over the objections of bureaucrats who feared exposure for corruption or inefficiency, Ndemo released online millions of official documents, making Kenya’s the first government in Africa and one of the first in the world to be completely data-open. Bitange’s ultimate goal was free email and mobile phone calls for every Kenyan. ‘The internet is a basic human right,’ he liked to say. If physical infrastructure allowed Africans to move, connect, trade and prosper, mobiles took that to a new level. They put freedom in every African’s hand.

As budget-conscious consumers, Africa’s mobile users overwhelmingly preferred the cheapest form of communication: text. That prompted a range of text-based innovations including Mxit, a South African social network based on texting, txteagle, a developing-world outsourcing network and mPedigree, a Ghanaian service that offered a central number to which customers could text the barcode of a medicine packet and find out whether the drug was counterfeit.

To make sure it was profiting fully from text, in March 2007 Kenya’s biggest mobile company, Safaricom, unveiled its own package of text services, which included a money transfer service the company called M-Pesa: ‘m’ for mobile and ‘pesa’ meaning money in Swahili. The idea was simple. A Safaricom subscriber would approach a Safaricom agent with some cash they wanted to transfer to another person, and that person’s mobile number. The agent would take the money and, for a small fee, send the credit to the recipient’s phone account. Soon the sender could upload credit to his own account, then send it directly to the other subscriber. It doesn’t sound like much. It wasn’t even original. By 2007, mobile companies in Japan and the Philippines had both been offering text-based money transfers for years.

M-Pesa’s growth, on the other hand, was extraordinary. Hundreds, then thousands of M-Pesa agents sprang up across the country, reaching 19,000 within a year. After eight months, a million people were using M-Pesa. By June 2010, 10 million were. In 2013, 17 million Safaricom subscribers–close to half the Kenyan population–were using M-Pesa to transfer $2 billion a month. That was equivalent to a third of Kenya’s national income and about 40 per cent more than all the coins, notes and current account balances in Kenya put together. Simply put: in Kenya, M-Pesa was bigger than cash.

Why? M-Pesa was more proof of Prahalad’s principles. Kenya’s banks had historically deemed most Kenyans too poor for an account. Why did the poor need a bank? As it happened, almost every poor Kenyan disagreed with that. Soon after Safaricom launched M-Pesa, it began to notice Kenyans were using M-Pesa not just to send money but as a substitute for a fully fledged bank. They would take their phone shopping and use it to transfer money to their grocer, their hairdresser, even their travel agent, in the same way a shopper would use a debit card in the rich world. They would also use it in places where plastic was useless, such as paying their gardener or buying a bus ticket or tipping the neighbourhood beggar a few cents at the traffic lights.

They used M-Pesa to save, too. That prompted Safaricom to link its M-Pesa accounts to actual bank accounts offered by Equity Bank and Kenya Commercial Bank. It was a neat reversal of the way credit checks worked in the West. There your bank account acted as the credit record necessary to obtain a mobile phone. In Kenya your prepaid mobile was your credit record and your passport to a bank account–and savings, loans, interest and plastic.

In the West, banks were brick-and-mortar institutions. In Africa, they were in the air. It took such a leap of imagination to grasp how such a startling amount of financial freedom had arrived in Africa almost instantly that, for half a decade, the rich world didn’t get it. By 2013, there were 50 mobile money services in Africa and Kenyan-style mobile banking was available in almost any developing country in the world, from Mexico to Iran to Nepal. The number of mobile banking users in the world had reached 600 million and was predicted to cross a billion by 2017. But in the US and Europe, mobile banking was still in its infancy.

The contrast between the crashing of American and European banks, however, and the rocketing fortunes of an African bank that was really a mobile phone company made Safaricom and its competitors impossible to ignore. Carol Realini, boss of a Californian mobile-banking company, Obopay, was emphatic. ‘Africa is the new Silicon Valley of banking,’ she said. ‘The future of banking is being defined here. The new models for what will be mainstream throughout the world are being incubated here. There are 100 countries around the world looking to Kenya and asking: “How do we do that?” Africa is going to change the world.’

The bigger mobile banking grew, the keener each new Kenyan developer became to write the code that would shape its next evolution. Shortly before I met Denis I attended a two-day mobile technology conference in Nairobi. As the first day began, the dozen or so European and Californian venture capitalists in the audience affected studied scepticism about the whole idea of African tech. But as the presentations proceeded, it became steadily less clear who, exactly, was out of their depth. Many of the Kenyan developers were focused on the future of money–or rather a future without money, as most of their audience understood it. The Kenyans were sure the phone would soon replace the wallet. ‘Our mobile money system is the alternative to cash in Africa,’ announced the 24-year-old vice-president of business development at a start-up called Kopo Kopo. The boss of a company called Zege Technologies said his rival cashless banking system went one better, offering ‘business at the speed of thought’. At first there were no questions. Then there were a lot.

After the conference, Denis told me he had decided not to make ‘just another mobile wallet’, as if that were the dullest thing in the world. Instead he proposed to secure every single mobile wallet against fraud. Eventually, predicted Denis, he would be protecting hundreds of millions of customers and handling trillions of dollars. He imagined Usalama as the Group 4 of the financial internet. ‘All our solutions are global,’ he said. ‘One of our products reduces ATM fraud by 90 per cent. We have an anti-credit-card-scamming product. We can report fraud live, as it happens.’

Almost as an advertising gimmick, Denis had developed a personal panic button that could be downloaded as a mobile app and which, when activated, would send an alarm to private security companies, banks and family, giving time and location. The high demand for that had turned it into a whole separate business that Denis hoped to roll out next in Nigeria and Ghana. ‘Everyone in the world needs security,’ said Denis. ‘And we can give it to them.’ Carol Realini was right, said Denis. ‘It’s Africa’s time to change the world,’ he said.

A growing population, commercial farming, remade cities, mobiles–these were the drivers of Africa’s growth. There were other factors common to rising prosperity anywhere: better education, health and democracy; diminishing conflict and corruption; cheaper wages than China; better language skills than India; and Africa’s physical proximity to pacey economies in Asia, the Middle East and Latin America.

By the turn of the twenty-first century, it was no longer accurate to regard Africa as a huge void. It was a waking giant. But every time I took a night flight across Africa’s blackened spaces, one question would return. When would Africa finally turn on the lights?

One day I drove out of Nairobi before dawn, heading west over the lip of the Rift and away from the city. By mid afternoon I was close to the Ugandan border, and in the midst of a patchwork of green maize fields ringed with sagging papaya trees I found the tin-and-grass-roof village of Kokete. I was there to meet 39-year-old Gladys Nange. We shook hands and she showed me around the maize plantation and chicken coops on her half-acre plot. Then she led me into the two-room, windowless hut that she shared with six children and her husband. ‘You hear about government plans to bring power cables here but it never comes,’ she said. ‘I can’t afford the $400 connection charge anyway.’

It was a perfect poverty trap. Gladys couldn’t afford power. Lack of power had, in turn, kept Gladys and her family poor. No light prevented her children from finishing their homework, so they did badly at school. No power meant that to charge her mobile phone, on which she checked maize and chicken prices, she had to walk five kilometres to the nearest working plug, whose owner charged $3 for the service. Even when Gladys could afford paraffin for her lamps, the fumes inside the tiny hut sometimes made the family so ill they had to stay home sick.

Spain, with a twentieth of Africa’s population, produces as much electricity as the entire continent. In 2014, a full 700 million Africans–two-thirds of the population–had no power lines and for them night still meant what it did when mankind first stepped out onto the savannah four million years ago: darkness and silence, an end to work, a time to sleep. The collective implications of life without power are grave. Economists reckon every 1 per cent shortfall in a country’s energy supply shaves 0.7 per cent off its economic growth. Kokete’s village chief, Francis Morogo, told me no one from Kokete had been to university, many had never even left the village and almost everyone lived on what they grew. ‘People here are really on the edge of nothing,’ he said. ‘They still have a hungry season between harvests.’ The chief waved a walking stick in a wide arc. ‘What you see here,’ he said, ‘is lives lived in the dark.’

I’d come to see Gladys because, two months before, in an experiment then unique on the continent, she’d swung a small solar panel onto her roof and run a cable back to a central yellow junction box linked to two LED lights and a mobile charger. It was an adaptation of prepaid mobiles to electricity, transcending the need for a national power grid. Gladys paid an initial $12 for the kit, made by a start-up spun out of Cambridge University in Britain. She paid off the rest of the $93 cost in weekly payments of $1.20 spread over 18 months by buying scratchcards and punching their code into a keypad on the junction box. At the end of her payments, Gladys could choose either to enjoy free power for as long as the panel lasted or upgrade to a better pack with more lights and power points.

The idea was simple. Its effect was close to miraculous. Gladys’ children could finish their homework, the house was no longer filled with noxious fumes and Gladys was saving money and planning to expand her chicken-farming business with bigger, electrified hatcheries. This was a change big enough to be seen from 30,000 feet.

Before I left, I asked Gladys to imagine her future. She thought for a moment, then laughed and opened her arms wide across the electric light falling all around her.

‘Brighter,’ she said.