This great battle for Egypt is what the Duke of Wellington called “A close-run Thing.”

—Winston Churchill, letter to Admiral Cunningham dated 1 May 1941

At the start of April 1941, flush from their victory at Matapan, the British surveyed their position in North Africa, the Middle East, and the Balkans with satisfaction. Imperial forces were completing the conquest of Italian East Africa, a royal coup in Yugoslavia had installed an anti-German government, and the Greeks seemed firmly ensconced in Albania. German airpower had proved troublesome to the Mediterranean Fleet, but not decisively so. Admiral Cunningham considered that the major area of concern “overshadowing everything else” was the position in Cyrenaica.1

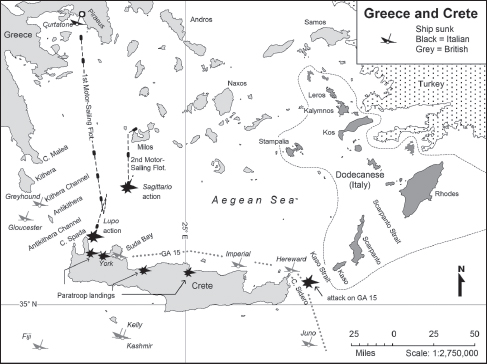

On 24 March 1941 Axis forces burst forth from El Agheila and swiftly erased Britain’s stunning conquests, taking Benghazi on 4 April and steamrolling to the Egyptian frontier two weeks later. A stream of men and equipment pouring into Tripoli enabled this turnabout. From October 1940 to January 1941 the Regia Marina landed a monthly average of 49,435 tons of materiel and 6,981 men; only 0.9 percent of the men and 3.9 percent of the materiel failed to arrive. From February through June 1941 the monthly averages rose to 89,563 tons and 17,912 men, respectively, with 5.1 percent of the men and 6.6 percent of the materiel lost en route.2 From this traffic the British sank four merchantmen in January, three in February, and another four in March. (See map 7.1.)

With Imperial troops in retreat, choking the Libyan supply line became critically important; under pressure from London, Cunningham reluctantly ordered four destroyers under the command of the 14th Destroyer Flotilla’s skilled Captain Mack to Malta to supplement the submarines and aircraft already operating there.3 These ships arrived on 11 April, the same day Axis troops encircled Tobruk and one day before Belgrade surrendered to the German army. Coincidentally, April was also the date by which Cunningham had proposed back in August 1940 to have Malta functioning as an offensive base for warships, although only about two-thirds of the tonnage he had estimated necessary had been delivered.

Map 7.1 Convoy Routes, April–May 1941

Mack’s first sorties, on the nights of 11 and 12 April, were unproductive. On 13 April a convoy of three troopships and two munitions ships departed Naples for Tripoli, escorted by the 8th Destroyer Squadron, following the customary route west of Sicily, past Cape Bon, and along the Kerkenah Banks. A Malta-based Maryland sighted the convoy on the morning of 15 April, and Mack’s destroyers weighed anchor that evening.

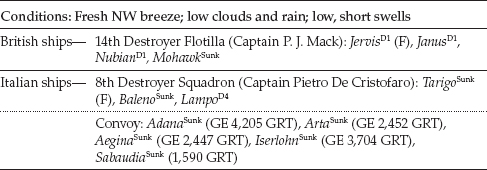

The convoy had experienced a rough passage. Heavy winds scattered the ships, and it had fallen four hours behind schedule by the time it regrouped off Cape Bon at 2200 on 15 April. Captain Pietro De Cristofaro, the escort commander, knew aircraft were shadowing his force through cloudy skies, although he had no idea the British had based a surface force at Malta. (See table 7.1.)

Table 7.1 Action off Sfax, 16 April 1941, 0220–0400

Conditions: Fresh NW breeze; low clouds and rain; low, short swells |

|

British ships— |

14th Destroyer Flotilla (Captain P. J. Mack): JervisD1 (F), JanusD1, NubianD1, MohawkSunk |

Italian ships— |

8th Destroyer Squadron (Captain Pietro De Cristofaro): TarigoSunk (F), BalenoSunk, LampoD4 |

|

Convoy: AdanaSunk (GE 4,205 GRT), ArtaSunk (GE 2,452 GRT), AeginaSunk (GE 2,447 GRT), IserlohnSunk (GE 3,704 GRT), SabaudiaSunk (1,590 GRT) |

After arriving at a point they estimated was well ahead of their target, the British swept northwest but saw nothing. In fact the convoy was farther inshore than expected and the destroyers passed it to port at 0145. At 0155, acting on a hunch, Mack turned south-southwest, and just three minutes later a sharp-eyed lookout aboard the flagship sighted shadows six miles ahead. The wind was gusting at forty miles per hour, and the air was heavy with dust blowing off the continent. As Mack maneuvered for twenty minutes to position the newly risen quarter moon behind the Axis ships, Italian and German lookouts saw nothing of the danger approaching them from astern. When he gave the order to open fire at 0220, Jervis, now heading southeast, was a mere twenty-four hundred yards off the destroyer Baleno’s starboard quarter.

The action that followed was typically confused.4 Jervis’s initial salvo missed Baleno, but Janus was on target and her 50-pound shells sliced through the Italian destroyer’s bridge, slaughtering her officers and the captain, who had just ordered his ship to make smoke. Then Jervis found the range, and within five minutes Baleno, hit repeatedly in the engine rooms, was adrift, burning from stem to stern. There was confusion about the source of this attack, but De Cristofaro saw the flat trajectory of tracers and brought Tarigo around from her position at the convoy’s head.

The rear British destroyers, Nubian and Mohawk, targeted Sabaudia, the convoy’s tail-end ship. Nubian’s captain wrote: “This vessel was hit about third salvo, there was an explosion and a large fire broke out aft.”5 As the two Tribal-class destroyers pushed up the convoy’s starboard side, Nubian engaged Iserlohn and Aegina, claiming hits on both, while Mohawk checked fire, as all targets seemed heavily engaged. Meanwhile the two Js mixed with the merchantmen at ranges from fifty to two thousand yards; in fact, Jervis barely avoided being rammed. They fired so rapidly that empty shell casings piled up around the mounts and interfered with the working of the guns.6 Iserlohn blazed up, and Janus launched three torpedoes toward Sabaudia, Iserlohn, and Aegina, which had clustered together.

At 0235 Nubian spotted Tarigo speeding north. De Cristofaro likewise saw the outline of a warship emerge from the smoke. When it opened fire he hesitated, thinking it might be Baleno. Then a lookout shouted that it was an English cruiser. Nubian and Tarigo traded salvos from a thousand yards. Metal shards cut through both vessels. One severed De Cristofaro’s leg, and he bled to death at his post.

Tarigo’s passage attracted the fire of the other British destroyers. Jervis hit the Italian’s bridge, sparking a blaze amidships. Janus could not train her mounts fast enough to track the rapidly moving target; she rushed two torpedoes into the water, but they missed astern. Tarigo likewise shot in haste, and her “tracer could be seen going high and wide.”7 Then at 0240 Jervis blasted Tarigo with a torpedo. Nubian and Mohawk passed, and Mohawk’s captain, Commander J. W. Eaton, considered the Italian flagship neutralized.

At 0245 Nubian crossed Arta’s bow at the convoy’s head. As Mohawk followed Arta attempted to ram, forcing Mohawk to veer hard to starboard. Suddenly a torpedo walloped Mohawk on the starboard side abreast the Y (farthest aft) mount, blowing away the ship’s aft section but leaving her propellers and rudder intact. Eaton, uncertain where the blow had originated, engaged Arta with his forward mounts. In fact, an enterprising ensign aboard Tarigo had manually aimed and fired the torpedo just a minute before.

Mack heard about Mohawk’s plight at 0252, and he turned toward the stricken ship, ordering her to burn recognition lights. Meanwhile Janus, cutting through the convoy at high speed, torpedoed Sabaudia and touched off the unfortunate ship’s cargo of munitions. Jervis, fifteen hundred yards away, “was showered with pieces of ammunition, etc. . . . [T]he sea around appeared as a boiling cauldron.”8 At 0253 the same ensign aimed another torpedo at Mohawk; it hit and exploded, and the large British destroyer began to settle.

Lampo, located on the convoy’s far side, was slow to enter action. First encountering Nubian, Lampo fired her guns and launched three torpedoes. Nubian’s counterblast staggered the Italian, heavily damaging her stern mount and steering mechanism. With many dead and wounded, Lampo retreated. She eventually grounded on Kerkenah Bank to keep from foundering.9 After dispatching Lampo, Nubian chased down Adana, which was fleeing southeast, and set her ablaze. Adana and Arta eventually joined Lampo on the banks. Baleno finally capsized on the morning of 17 April.

Janus found Tarigo and pumped rapid salvos into the helpless ship for ten minutes before moving on. However, the Italian refused to sink and at 0311 launched a torpedo at Jervis, which passed under the British ship’s bridge. Jervis pummeled Tarigo until her guns no longer bore and then ordered Janus to return and sink her, which she did.

The three surviving British destroyers “suffered no casualties and slight damage from splinters.”10 They lingered for an hour, rescuing all but forty-one of Mohawk’s men. Supermarina learned of the disaster the next day and mounted a large rescue effort, but the Axis still lost 1,700 men, 300 vehicles, and 3,500 tons of supplies.

Convoys continued despite this debacle, however. Two arrived in Tripoli without loss four days later, and Supermarina was able to regard the destruction of the Tarigo convoy as an anomaly based upon lucky air reconnaissance.

The fact that it had taken the Royal Navy ten months to intercept successfully an African convoy with surface warships demonstrated the difficulty of the task. Churchill calculated that the flow of supplies could be more easily cut if there was no place to unload them; via the First Sea Lord, he ordered the Mediterranean Fleet to use Barham and an old C-class cruiser to conduct a close-range bombardment of Tripoli and then scuttle themselves to block the port. This plan horrified Admiral Cunningham, who protested, “I am of the opinion that if these men [aboard Barham and Caledon] are sent into this operation which must involve certain capture and heavy casualties without knowing what they are in for, the whole confidence of the personnel of the fleet in the higher command . . . will be seriously jeopardized if not entirely lost.”11 Finally London backed down, and as a compromise, Cunningham reluctantly agreed to bombard the port instead.

Elements of the Mediterranean Fleet departed Alexandria on 18 April, combining the bombardment with a supply operation to Malta. Mack’s flotilla left Malta on 20 April to shepherd four empty freighters partway back to Alexandria. After completing these movements the fleet turned south. Against expectations, Italian aircraft failed to spot the British during their approach. Formidable, with Orion, Perth, Ajax, and four destroyers, stood by while the battleships moved in. The port, which occupied an area roughly one mile square, was crowded that morning with a dozen freighters and more than a hundred small vessels like minesweepers, barges, tugs, and water tankers. Six warships were also present. (See table 7.2.)

Table 7.2 Tripoli Harbor, 21 April 1941, 0502–0545

Conditions: Calm sea, poor visibility |

|

British ships— |

1st Battle Squadron (Admiral A. B. C. Cunningham): BB: Warspite, Barham, ValiantD1; CL: Gloucester |

|

14th Destroyer Flotilla (Captain P. J. Mack): Jervis (F), JanusD1, Juno, Jaguar, Hotspur, Havock, Hero, Hasty, Hereward |

Italian ships— |

11th Destroyer Squadron (Captain Luciano Bigi): AviereD1, Camicia Nera, GeniereD2 |

|

TB: PartenopeD1, Calliope, Orione |

The submarine Truant acted as a marker for the battleships so they would know their exact position. However, she was several thousand yards east of her intended location, causing the bombardment to be conducted at a closer range than planned. At 0440 the British warships “circled the Truant in line ahead just like rounding a buoy.” Cunningham remembered, “The silence was only broken by the rippling sound of our bow waves, the wheeze of air pumps, and the muffled twitter of a boatswain’s pipe on the Warspite’s messdeck.”12 Hotspur, Havock, Hero, and Hasty led by two thousand yards, sweeping for mines; then came Warspite, Valiant, Barham, and Gloucester, while Juno and Jaguar screened the heavy ships to starboard and Jervis, Janus, and Hereward screened to port. At 0502 Warspite opened fire from 12,400 yards.

The fleet steamed east, shooting steadily, until 0524. The first impacts raised “a vast cloud of dust and smoke [which] thickened by shell bursts, made it difficult for the spotting aircraft and practically impossible for the ships to observe the fall of shot.”13 The British were off target, and the Italian shore batteries, two army-manned positions with eight formerly Austro-Hungarian 7.5-inch/39 guns, held fire so as not to provide a point of aim. However, when the column simultaneously came about to the west, putting Gloucester in the lead, accuracy improved, and the batteries and destroyers in the harbor engaged the British gun flashes. The battleships were beyond range, but shells straddled Hereward, and splinters lightly damaged Janus.

At 0545 after expending 478 15-inch, 1,500 6-inch, and 4.7-inch rounds, the British battle line ceased fire and continued west at maximum speed. These 530 tons of ordinance sank the freighters Assiria (2,704 GRT) and Marocchino (1,524 GRT), as well as the customs boat Cicconetti (of sixty tons). Splinters damaged the steamship Sabbia (5,788 GRT). One of Gloucester’s shells hit Geniere’s funnel, and pieces from this blast damaged Aviere. Fragments from a different round sprayed Partenope and killed her captain. Many of the heavy shells fell in the city, demolishing a dirigible hangar at the airport. The docks were moderately damaged, but the convoy of four steamers that had arrived the day before nonetheless finished unloading that afternoon. An air attack delivered an hour before the bombardment was ineffective.

This blow caught Italy in the process of expanding the minefields protecting Tripoli; in fact, two existing fields had been cleared in mid-April because they interfered with the process of sowing the new barrage. Valiant did touch a mine during the operation and was slightly damaged.14 The new fields, after completion, sank on 18 August 1941 the British submarine P32, the wreck of which supplied Regia Marina code breakers with useful material. Then, in December 1941, Force K ran onto the field, losing one cruiser and one destroyer sunk and two cruisers damaged.15

British surface forces from Malta continued to probe for Axis convoys but without much success. On the night of 23 April Mack’s flotilla sailed after air reconnaissance reported five transports. At 0024 on 24 April Juno found the armed motor ship Egeo (3,311 tons, two 4.7-inch/45 guns, and fifteen knots) sailing independently and, after a prolonged engagement, finally torpedoed and sank the outgunned auxiliary. The convoy saw the flash of gunfire on the southern horizon and turned away. Mack searched for but failed to find the greater prize.

On 28 April the 5th Destroyer Flotilla, under Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten, replaced Mack’s 14th Flotilla. Gloucester stayed in Malta to provide support, because the Italians had begun to supplement their escorts with pairs of light cruisers. Then, on 2 May while entering Valletta’s Grand Harbor, Jersey detonated a German air-dropped magnetic mine and sank, blocking the narrow entrance channel. This closed the port for a week while the wreck was blasted away. Stranded outside, Gloucester, Kipling, and Kashmir proceeded to Gibraltar instead of Alexandria, unwittingly avoiding an encounter with the Italian cruiser Abruzzi and a destroyer, which had been hurriedly detached from a convoy to intercept them after an Italian cryptologist read a signal regarding their situation.

If at the beginning of April the British Empire’s situation had seemed good, by the end of the month it was terrible. Axis armies had driven to the borders of Egypt and ejected Imperial troops from Greece, the last Allied toehold on the European mainland. Operation Lustre, the buildup in Greece, lasted from 4 March to 24 April 1941. So “confused and constantly changing” was the military situation that Operation Demon, the evacuation of Greece, commenced the day Lustre ended.16 Demon ran six days—the time it took the German army to close the Aegean coast. (See map 7.2.)

Crete served as a way station for the evacuation convoys, and on 29 April transports crowded Suda Bay. Vice Admiral Pridham-Wippell, commanding Operation Demon, formed Convoy GA 15 to evacuate to Egypt 6,232 troops and 4,699 others, including Italian prisoners of war, nurses, and consular staff.

GA 15 sailed at 1100 and proceeded east at ten knots toward Kaso Strait, joined at 1400 by Force B. Pridham-Wippell chose the eastern passage around Crete; although the route was closer to Italian bases in the Dodecanese, he considered it, after the Gavdos experience, safer from surface attacks, except from destroyers and MAS boats at night. (See table 7.3.)

Table 7.3 Attack on Convoy GA 15, 29–30 April 1941, 2315–0300

Conditions: New moon, set 2248 |

|

Allied ships— |

Convoy Escort CLA: Carlisle; DD: Kandahar, Kingston, Decoy, Defender; DS: Auckland (NZ); DC: Hyacinth |

|

Force B: (Vice Admiral Pridham-Wippell): CL: Orion (F) Ajax, Perth (AU), Phoebe; DD: Hasty, Hereward, Nubian |

|

Convoy GA 15: Delane (6,045 GRT), Thurland Castle (6,372 GRT), Comliebank (5,149 GRT), Corinthia (3,701 GRT), Itria (6,845 GRT), Ionia (1,936 GRT), Brambleleaf (5,917 GRT) |

Italian ships— |

DD: Crispi; TB: Lince, Libra |

The convoy rounded Cape Sidero, on Crete’s northeastern extremity, and entered Kaso Strait after dark. Beginning at 2315, Crispi, Lince, and Libra, sailing out of Leros, made several unsuccessful torpedo attacks as the convoy transited the restricted passage. Lince reported hitting a large destroyer with two torpedoes, while Libra claimed a probable hit. Hasty, Hereward, and Nubian stood them off with heavy gunfire until the Italian flotilla disengaged at 0300. Decoy encountered on the other flank a torpedo boat, which, in the dark, she misidentified as a much smaller MAS boat, and opened fire: “We heard the E-boat’s engines start with a roar and by the time we could see again after the gun flash there was only a white streak of a wake and a noise like an aeroplane fading into the blackness.”17

Pridham-Wippell’s report noted, “Some torpedoes were fired but no damage was caused to the convoy. Own destroyers chased the enemy off several times.”18 Rear Admiral H. B. Rawlings, with Barham, Valiant, Formidable, and six destroyers, joined the convoy at 0600 on 30 April about eighty miles south of Kaso Strait, and GA 15 arrived safely in Alexandria the next day.

While Imperial troops could be rescued from Greece, they had to leave their heavy equipment behind. In addition, the retreat from Libya had cost the British 2nd Armored Division most of its tanks. In this crisis the British War Cabinet decided to send equipment to Egypt directly via the Mediterranean rather than around Africa. Code named Operation Tiger, the plan called for Force H and the Mediterranean Fleet to combine efforts to get a fast convoy of five merchant ships loaded with 295 tanks and fifty-three Hurricanes, along with the battleship Queen Elizabeth and the cruisers Naiad and Fiji, from Gibraltar to Alexandria. Simultaneously, convoys from Alexandria would reinforce Malta.

Clouds, fog, occasional rain, and “the luck of the gods” favored Force H and reduced the level of Axis air attacks.19 An Italian bomber heavily damaged the destroyer Fortune on 19 May, and Queen Elizabeth barely avoided a torpedo attack during the night of 8 May. Renown and Ark Royal likewise dodged Italian bombs and torpedoes. Somerville wrote, “We were combing one [torpedo] successfully [when] the damn thing suddenly altered 90° to Port and came straight for our bow. Now we’re for it I thought but, would you believe it, the damn thing had finished its run & I watched it sinking about 10 yards from the ship.”20 Supermarina dispatched the light cruisers Abruzzi, Garibaldi, Bande Nere, and Cadorna and five destroyers from Palermo on 8 May to set an ambush, believing the British intended to bombard that port, but rough weather prevented contact—probably fortunately, given their opposition’s strength. “The information received in those days from the air reconnaissance service was so confused that Supermarina did not have the least idea that a British battleship, the Queen Elizabeth, had made the passage eastward with the convoy.”21 The convoy’s only loss was the steamer Empire Song (9,228 GRT), which hit a mine off Malta on 9 May.

The British also conducted a number of ancillary actions, including a bombardment of Benghazi on the way in by Ajax and destroyers Havock, Hotspur, and Imperial and on the way back by 5th Destroyer Flotilla. The Ajax force also swept the waters south of Benghazi and sank the Italian steamers Tenace (1,142 GRT) and Capitano Cecchi (2,321 GRT) on 8 May. Churchill “was delighted to learn that this vital convoy, on which [his] hopes were set, had come safely through the Narrows.”22 But, even before it reached port his thoughts had turned to Crete.

On 9 April the Middle Eastern command decided to hold Crete, because “from the naval point of view it was vital.”23 After being swept from the continent, Imperial and Greek troops organized, in an atmosphere of haste and defeat, to defend the island. Luftwaffe Enigma gave the British two weeks’ notice of Germany’s intention to assault Crete with paratroopers, and the Mediterranean Fleet, which had been built up to four battleships, one carrier, ten light cruisers, and twenty-nine destroyers, girded for action.24 Cunningham was “quite sure that if the soldiers were given two or three days to deal with the airborne troops without interference by sea-borne powers, Crete could be held.”25 On 15 May cruiser/destroyer squadrons began to patrol the island’s approaches. Reconnaissance had sighted three battleships at Taranto, so the heavy units loitered southwest of the island ready to pounce if the Italians sortied. Cunningham did not know that the Luftwaffe had asked the Regia Marina to stay away, ostensibly because the aerial forces committed to the invasion were not trained to tell the difference between friend and foe.

On 20 May German paratroopers descended on Crete. Imperial troops, principally New Zealanders and Australians, and about ten thousand Greek levies resisted stoutly, and after the first day it appeared the German attack would fail. Conventional wisdom, in fact, held that paratroopers could not defeat emplaced regular troops; thus even before the first planes took off, a largely Greek manned collection of twenty-one small steamers, caiques, and fishing craft, dubbed the 1st Motor-Sailing Flotilla, departed Piraeus crammed with 2,331 German mountain troops to reinforce the precarious aerial toeholds.

On the night of 19 May torpedo boat Sirio, the convoy’s sole escort, damaged her propeller near Milos, eighty miles north of Crete. The Aegean command immediately dispatched Curtatone to replace her, but she struck a Greek mine off Piraeus and sank. The job of escort then rotated to Lupo. This latter ship, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Mimbelli, located the scattered formation at dawn on 21 May fifty miles south of Milos. There were only thirty miles left to travel—an easy journey in daylight even at an average speed of three knots—but at 0715 the sector commander, the German “Admiral Southeast,” Admiral Karl Schuster, ordered the convoy to wait in place. Then, based on incorrect Luftwaffe reports of British ships between Crete and Milos, he ordered it to reverse course. By the time Schuster had sorted out the intelligence situation and radioed orders to proceed, the time was 1100, and the convoy was eight miles farther north than it had been four hours before. A daytime passage under the Luftwaffe’s protective umbrella was no longer possible.

Lupo led the ragged flotilla south once again, but during the afternoon headwinds kicked up a heavy sea through which the caiques wallowed at barely two knots. Evening brought low clouds and visibility between two and four thousand yards. By 2230 the convoy was five miles north-northeast of Cape Spada after a plodding journey of nearly three days.

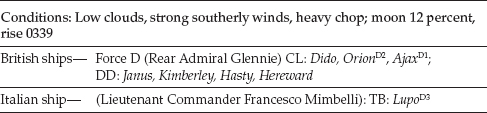

As the 1st Motor-Sailing Flotilla labored south, British air reconnaissance had “reported groups of small craft, escorted by destroyers, steering towards Crete from Milo.”26 On the morning of 21 May Cunningham received signal intelligence that Canea would be attacked from the sea during the day and accordingly deployed four surface action forces.27 With darkness, three groups penetrated the Aegean. The Antikithera Strait, north of Cape Spada, was the responsibility of Force D, commanded by Rear Admiral Irvine G. Glennie. He probed north with four destroyers in a line of bearing and his three cruisers following in line ahead. (See table 7.4.)

Table 7.4 Lupo Convoy Action, 21–22 May 1941, 2230–0030

Conditions: Low clouds, strong southerly winds, heavy chop; moon 12 percent, rise 0339 |

|

British ships— |

Force D (Rear Admiral Glennie) CL: Dido, OrionD2, AjaxD1; DD: Janus, Kimberley, Hasty, Hereward |

Italian ship— |

(Lieutenant Commander Francesco Mimbelli): TB: LupoD3 |

At 2229 Janus, which had lost contact with the other destroyers, sighted a shape ahead and rapidly closed range, believing it was Kimberley.28 In fact, she had stumbled upon Lupo leading the convoy. At 2233, according to Mimbelli’s report, an Italian lookout signaled, “1,000–1,200 meters distance, an enemy cruiser to starboard bearing approximately 20 degrees off the bow.”29 The Italian ship attempted to launch a pair of torpedoes from her stern tubes (Lupo was configured with single tubes mounted fore and aft on each beam) but Janus made a slight alteration in course that unintentionally ruined the torpedo boat’s set-up. Mimbelli ordered a smoke screen and held fire as his ship passed through the line of British destroyers.

At 2235, the Italian ship spotted Dido looming out of the dark beyond Janus. The cruiser had already detected Lupo, and at nearly the same moment British gunfire erupted. Lupo launched her forward torpedoes from seven hundred yards and then returned fire. In response, Dido turned sharply to starboard. Lupo held steady and crossed the cruiser’s bow to starboard. Then Orion suddenly appeared dead ahead, in the process of turning to conform with the flagship’s maneuver. Mimbelli pressed on. He later reported, “I passed just meters, repeat meters, beneath [Orion’s] stern.” During this three-minute span, the torpedo boat’s three 3.9-inch guns and 20-mm/65 shot continuously to starboard, claiming hits, although the British reported that only 20-mm gunfire from Dido struck Orion, killing two and wounding nine men. After passing Orion, Mimbelli observed a vivid flash illuminating Dido, and he claimed a hit. In fact, a torpedo had passed astern of Dido and exploded in Orion’s wake, slightly warping the second crusier’s hull. The shock also shook her masts and reduced her speed to twenty-five knots.30

With his ship lucky to still be afloat and noting that “some enemy ships, instead of concentrating on [Lupo] were exchanging cannon-fire between themselves,” Mimbelli used the confusion to escape at high speed. The British believed they sunk her. One participant aboard Ajax, the third ship in the British cruiser line, related, “[Ajax] suddenly came across a small Italian destroyer in the mist and smoke of the melee. She was no more than a few hundred yards away and Ajax blew her to bits with one six inch salvo.”31 In fact, the cruisers struck Lupo eighteen times (but only three shells exploded), killing two and wounding twenty-six men. Somehow, all this ordnance missed the thin-skinned torpedo boat’s engines.32

With the escort brushed aside, only darkness, thick weather, and confusion protected the caiques. For their part, S8’s experience was typical. She carried 125 soldiers and sailed at the formation’s rear, following the stern lights of the vessels ahead. Her commander’s biggest worry was his ship’s delicate engine. Then he spotted a vast shape looming from the darkness, and his worries multiplied. Searchlights played over the water, and bright muzzle flashes temporarily blinded him. Two salvos passed overhead. He saw an explosion, and flares arced into the sky. The cruiser rushed by so close that her machine guns could barely rake the crowded boat.

For two hours the British crisscrossed the area, sweeping the dark sea with searchlights. Warships passed S8 twice, perforating her deck and hull with automatic weapons. To the south her men could see “five torching hulks light a large semicircle; some burn out, and new torches to the northwest light up—all told seven.”33 The ship had her mast shot in half, but the men stayed aboard. At 0300 the British withdrew, and after calm returned S8 headed north. In addition to the damage suffered by Dido, Ajax bent her bow by ramming a caique.

Overall, the 1st German Motor-Sailing Flotilla lost eight of fourteen units in this clash. Force D had put eight hundred men into the water, of whom 324 drowned.34

Early on 22 May the 2nd German Motor-Sailing Flotilla, thirty small steamers and caiques loaded with four thousand German troops, departed Milos escorted by the torpedo boat Sagittario. At 0830, when the convoy had reached a point thirty miles south of Milos, Admiral Schuster ordered a retreat due to reports of British ships in the area, this time correctly—Force C, under Rear Admiral E. L. S. King, was indeed hunting the convoy. King was not to have much to show for his risky excursion north. At 0830 Perth bagged a straggler from the 1st Motor-Sailing Flotilla, and Mack’s destroyers sank a small steamer not involved in the invasion. Then King ran into the convoy’s tail end. (See table 7.5.)

Table 7.5 Sagittario Convoy Action, 22 May 1941, 0840–0930

Conditions: Clear weather, good visibility |

|

Allied ships— |

Force C (Rear Admiral E. L. S. King): CL: Naiad, Perth (AU); CLA: Calcutta, Carlisle; DD: Kandahar, KingstonD1, Nubian |

Italian ship— |

(Lieutenant Giuseppe Cigala Fulgosi): TB: Sagittario |

The withdrawal order found the flotilla somewhat scattered. Sagittario was collecting stragglers when, at 0847, she spotted the unwelcome sight of smoke and then masts on the southeastern horizon. Lieutenant Fulgosi ordered the transports to disperse while he laid smoke in their wakes. Then, to buy more time, Sagittario charged the British formation, opening fire at 0904 from thirteen thousand yards. Kingston, sailing in the British van, traded salvos with Sagittario, and the torpedo boat tagged the large British destroyer twice on the bridge with 3.9-inch shells.35 Even when Perth and Naiad engaged the Italian pressed on, closing to eight thousand yards and then launching four torpedoes at the cruisers.

At 0914 Italian observers reported brown smoke rising from the second cruiser in the enemy line (Naiad), and this caused Fulgosi to claim that one of his torpedoes had scored a hit.36

At 0928, with the enemy hidden by smoke, Admiral King decided to withdraw west—he did not realized how many small transports were nearby, Carlisle had unrepaired damage that limited his squadron’s speed to twenty knots, and antiair ammunition was running low. Every mile north brought him a mile closer to German airfields. Cunningham later condemned this decision, writing that King’s “failure to polish off the caique convoy” was the principal mistake made during the entire operation off Greece. Churchill sniffed: “The Rear-Admiral’s retirement did not save his squadron from the air attack. He probably suffered as much loss in his withdrawal as he would have done in destroying the convoy.”37 In retrospect, these harsh judgments seem unfair and to have been inspired by the losses subsequently suffered throughout the campaign without a naval victory to balance them.

In the end Crete succumbed to the paratroopers in a contest of wills. By 26 May the German situation had become so desperate that Wehrmacht staff requested Italian assistance, which Mussolini gleefully provided. That same day the Imperial commander, General Bernard Freyberg, advised Cairo that his troops had reached the limit of their endurance and received permission to withdraw.38 The only significant body of Axis troops to arrive by sea was a force of three thousand Italians that landed near Cape Sidero on 28 May, occupying the eastern part of the island against slight opposition.

Supporting the Imperial troops on Crete and then withdrawing seventeen thousand of them cost the Mediterranean Fleet dearly. On 21 May Italian aircraft sank Juno and damaged Ajax. On the morning of 22 May German planes damaged light cruisers Carlisle and Naiad (assuming the torpedo hit on Naiad was aerial, not surface launched) from Admiral King’s squadron. That afternoon German aircraft hit Warspite and sank the long-suffering Gloucester, with the loss of 693 men, and destroyer Greyhound. That evening German aircraft crippled Fiji and she was subsequently scuttled, while Carlisle, Naiad, and Valiant sustained lighter damage. One brief account can represent hundreds. A lieutenant aboard the destroyer Decoy was to recall,

We were so placed on the screen that we were about abeam of the leading battleship, Warspite, and I happened to be watching her when suddenly two Messerschmitts appeared from high out of the blue diving on to her from right ahead. At the same moment they were spotted from Warspite and the barrage crashed out, but we saw a stick of bombs leave each plane as it dived through the pom-pom bursts. I remember shouting to the Captain “They’ve got her, sir!” and his shouting back, “I think they’ll miss.” But one at least did not, and there was a cloud of smoke, followed by masses of white steam which almost hid the ship.39

The 5th Destroyer Flotilla shelled the German position at Maleme on the night of 22 May, but German aircraft jumped the flotilla as it sped south after the attack, sinking Kashmir and Kelly. That same day German fighter-bombers destroyed five MTBs in Suda Bay.

In a highly questionable operation ordered by Cunningham, Formidable raided the German air base at Scarpanto on 26 May with six Albacores escorted by two Fulmars, inflicting light damage. While they were withdrawing, a German counterattack smashed the carrier, driving her to the United States for repairs. An Italian bomber crippled Nubian the same day, and Barham received moderate damage the next. The day after that the British command decided to withdraw, so the navy suspended its attempts to reinforce the island and concentrated on evacuating the survivors.

On 28 May Italian bombers hit Ajax and the destroyer Imperial. Imperial was scuttled, being too damaged to escape.

On 29 May German aircraft badly damaged the cruisers Dido and Orion (causing 540 casualties among the thousand soldiers crowded aboard Orion) and crippled Hereward, which was likewise loaded with troops. She was later scuttled in the face of an attack by Italian MAS boats.

On 30 May German aircraft hit Perth and the destroyer Kelvin.

On 31 May German aircraft damaged the destroyer Napier.

The final blow in this torturous campaign fell on 1 June, when German bombers sank the antiaircraft cruiser Calcutta. Altogether 2,011 Royal Navy personnel died in the battle for Crete.

One solace the British took from this miserable sequence of events was that the Italian battle fleet never intervened. This lack of activity they ascribed to the impact of the Battle of Matapan. In fact, on 1 May the German naval attaché in Rome had advised Comando Supremo that the Germans would conduct a “blitz” operation against Crete but had not divulged the date or plan. The Germans asked only for the support of the two torpedo boat squadrons assigned to the German zone.40 Because the British were privy to the Lutfwaffe signals and the Italians were not, London knew German plans and intentions better than did Rome. On 14 May Comando Supremo considered a fleet sortie, but Supermarina, which did not appreciate the Royal Navy’s dire situation, judged it had enough destroyers to escort either convoys or the battle fleet but not both. Admiral Riccardi did not wish to risk the few large ships that remained operational, considering that it was their presence as a fleet in being that kept the sea lanes to Africa open. However, as Iachino concluded postwar, “Now knowing how things were, we can say that the best solution for us would have been to use the fleet to jab toward Crete to alarm the enemy and make him suspend operation ‘Demon,’ and then retire before coming into contact with the English heavy ships.”41

Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, Force H, using the aircraft carriers Ark Royal and either Furious or Victorious, concentrated on delivering fighters to Malta. On 19–22 May, in Operation Splice, Somerville’s squadron flew forty-eight Hurricanes to Malta without loss. On 5–7 June, Operation Rocket sent thirty-five Hurricanes to Malta without loss. On 13–15 June, in Operation Tracer, forty-seven Hurricanes took off for Malta, of which forty-three arrived. Operation Railway, which ran from 26 June to 1 July, delivered fifty-seven Hurricanes.

The Axis reconquest of Cyrenaica in April 1941 was only partially successful, as Imperial troops retained Tobruk. However, the besieged garrison needed to be maintained, requiring the dedication of the 10th Destroyer Flotilla and various auxiliaries to that task. These ships began making almost nightly runs from Alexandria to Tobruk (except during the height of the battle for Crete) on 5 May. They unloaded and left as quickly as possible, to minimize the exposure to air attacks on the return voyage. One participant recalled, “Having berthed, all hands turned-to and pitched our cargo into waiting lighters. Boxes and sacks of provisions stowed on the upper deck to a height of four or five feet were simply flung over the side while ammunition and land mines . . . were slid down chutes. . . . Everyone worked like demons, for the sooner we got away the further from enemy air bases and the nearer to our own fighter protection we should be at dawn. We never stayed longer than an hour.”42 Nonetheless, Axis aircraft sank the sloop Auckland on 24 June, destroyer Waterhen on 29 June, and destroyer Defender on 11 July.

The Regia Marina focused on supplying Libya and on laying minefields. The navy’s fuel situation had become critical, with only 342,000 tons in reserve.43 The two operational battleships, Doria and Cesare, kept to their base at Naples, and the cruisers saw only limited use providing distant cover for African convoys. Nonetheless, during May and June 1941 the following convoys reached Libya with the loss of only one ship among them:

1 May of five ships, unsuccessfully attacked by air and submarines

1 May of four ships, unsuccessfully attacked by aircraft

5 May of seven ships, unsuccessfully attacked by aircraft

13 May of six ships, arrived without incident

14 May of six ships, arrived without incident

21 May of seven ships, unsuccessfully attacked by submarine

25 May of four passenger liners, liner Conte Rosso (17,879 tons) sunk by a submarine

5 June of four ships, arrived without incident

9 June of three transports, arrived without incident

12 June of six ships, arrived without incident

24 June of five ships, unsuccessfully attacked by aircraft

29 June of four transports, unsuccessfully attacked by aircraft.

While it was business as usual at sea, on 15 June the British launched Operation Battleaxe, an ambitious offensive intended to drive past Tobruk and compensate for the loss of Crete by regaining the air bases between Sollum and Derna. However, Battleaxe failed to reach even its initial objectives, as Axis antitank guns chewed up most of the tanks delivered by the Tiger convoy. Even as this operation began, however, the British were undertaking other offensives in Iraq and Syria.