The Italians have made heavy sacrifices in a hard and bloody war, and have thereby proved that it is not weakness or fear in themselves that have been the mainsprings of [the armistice]. For the individual Italian, who possess a special, often an exaggerated, feeling of honor, the defection from his ally was doubtless extremely painful.

—Admiral Weichold, writing postwar, quoted in Hitler’s Admirals

Even before the conclusion of the Tunisian campaign members of Italy’s leadership contemplated defeat. When Tripoli fell on 23 January 1943, Admiral Maugeri, now head of Italy’s naval intelligence, recorded in his diary, “Who could have thought it possible a year ago when we reasonably had hopes of conquering? . . . [But] our situation now seems clear and sharp to me: we have lost the war.” A week later, upon the occasion of General Vittorio Ambrosio’s promotion to Comando Supremo’s chief of staff, Ciano wrote, “under present conditions, I don’t think even a Napoleon Bonaparte could work miracles.”1 Mussolini hoped that a separate peace with the Soviet Union would save his regime. The Germans, with potentially decisive weapons like jet aircraft, missiles, and true submarines, in the pipeline remained committed to total victory.

Even after the loss of Africa, Italy still maintained a vital maritime traffic along its coasts and with its islands, which the British, continuing to rely upon signals intelligence, took every opportunity to disrupt.

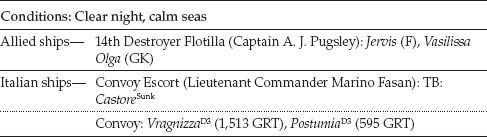

In response to intelligence that a convoy had departed Taranto bound for Messina, Jervis and Vasilissa Olga sortied from Malta on 1 June. The flotilla commander, Captain A. J. Pugsley, who was not privy to Ultra, would recall, “We had hardly got well away before a report came in that a small convoy had been sighted, southbound along the ‘foot’ of Italy. . . . A hurried consultation of the chart and a stepping-off of distances with the dividers and I knew that there would just be time enough to intercept the convoy, ‘give it the works’ and get back under air cover by daylight.”2 (See table 12.1.)

Table 12.1 Messina Convoy, 2 June 1943, 0134–0315

Conditions: Clear night, calm seas |

|

Allied ships— |

14th Destroyer Flotilla (Captain A. J. Pugsley): Jervis (F), Vasilissa Olga (GK) |

Italian ships— |

Convoy Escort (Lieutenant Commander Marino Fasan): TB: CastoreSunk |

|

Convoy: VragnizzaD3 (1,513 GRT), PostumiaD3 (595 GRT) |

Pugsley’s flotilla ran to the convoy’s farthest possible position and then turned back along its estimated track. At 0134 off Cape Spartivento they sighted two small steamers. The destroyers altered course and approached undetected. Upon their word, an ASV Wellington dropped flares. “The fire gongs clanged and the ship reeled as the 4.7s opened up at a range of 2,000 yards. The first shots hit the merchantman squarely. There was a dull red glow as the shells burst inside her.”3

After eight salvos, the British flagship shifted fire to Postumia. Then Castore, which had been leading the convoy, counterattacked, sending shells whistling overhead. Jervis immediately targeted the escort and claimed first-salvos hits, forcing Castore to lay smoke and turn away. The Allied destroyers chased into the muck to within a mile of shore but lost contact. The aircraft, however, continued to drop flares, and in their light Pugsley finally saw Castore rounding back, aiming her torpedoes. “Leading [Vasilissa Olga] past her on an opposite course, once again the guns found their mark before the enemy could make any effective reply.”4 Shells wrecked Castore’s steering gear, and she finally sank offshore at 0315.5 Pugsley’s flotilla also claimed the destruction of the merchant ships, but in fact, although damaged, they reached Messina, their destination.

Jervis only expended 142 4.7-inch rounds and one torpedo. On the high-speed return journey Vasilissa Olga suffered a boiler breakdown that left her dead in the water for an hour. Nonetheless, the two arrived at Malta undamaged at 1335 on 2 June.

Following their expulsion from Africa, the German and Italian high commands expected the Allies to strike across the Mediterranean by invading Sicily, Sardinia, or Greece. In fact, at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, following “some of the most arduous negotiations ever to occur between the two allies,” they decided to invade Sicily. This choice was driven by convenience and the need to completely clear the sea lanes through the Sicilian Channel; it was also seen as a way to placate Stalin’s demands for a second front. However, “there was no agreement on the matter of the Mediterranean verses cross-Channel strategy, no agreement on what to do beyond Sicily, no agreement even that knocking Italy out of the war was the immediate objective of the Anglo-American strategy.”6

After the capture of Pantelleria in June and with growing indications that Sicily was the enemy’s next target, it seemed time for the Regia Marina to hazard the battle fleet, against the Allied juggernaut. Although continually battered by air strikes, the fleet could deploy Vittorio Veneto and Littorio, along with three light cruisers and eleven destroyers. The problem was that in order to intervene, this squadron needed to steam five hundred miles under enemy-dominated skies—a twenty-five-hour journey at twenty knots. Upon reaching the decisive zone, the survivors would face four battleships, two fleet carriers, six light cruisers, and eighteen destroyers. Based at Taranto the Regia Marina had Doria and Duilio (both recently reactivated), a light cruiser, and a destroyer. The British waited with the modern battleships King George V and Howe, and six destroyers, should the untrained Italian crews venture to sea. On top of this the Allies had nine cruisers and 104 destroyers supporting the amphibious fleet. An American historian asked, “Would any modern navy, except the Japanese, have sought battle under like conditions?”7 (See map 12.1.)

When the Allies mounted their massive amphibious assault against Sicily on 10 July, the only Axis naval resistance came from submarines and motor torpedo boats. The submarines sank two LSTs, five merchant ships, and a tanker, at the cost of three German and nine Italian boats.8 The MTBs accomplished less: “The few serviceable [German] boats sailed a handful of torpedo missions, all frustrated by strong defences.”9 The Allies won their beachheads and progressed inland.

Facing the prospect of having the Adriatic cut off from the west coast, the Regia Marina decided to reinforce the Taranto squadron with a fast intruder unit, the new cruiser Scipione Africano. She departed La Spezia on 15 July and reached the Straits of Messina at 0200 on 17 July, after a stopover in Naples forced by a British sighting. While steaming on the last leg of her dangerous journey, she encountered four British MTBs off Reggio. The Allied commander reported, “I was caught completely napping. We were lying with engines stopped . . . in a flat calm with a full moon to the south silhouetting us nicely. . . . We never dreamed that a cruiser would be able to get down there unseen through all our patrols.”10 As Scipione steamed straight for them, working up to thirty knots, the boats maneuvered in pairs to get on each side of the enemy’s bow. The two boats to the west, MTB260 and 313, fired three close-range torpedoes. Scipione’s captain reported, “The torpedoes had not touched the water when, at my order, all of Scipione’s weapons, cannons and machine guns, opened fire on them, a fire so precise and violent as to amaze even me, though I knew the ship’s capabilities.”11 On the east side MTB316 was preparing to launch when a 5.3-inch salvo demolished her and slaughtered the entire crew. The cruiser burst through the enemy line at thirty-six knots and continued south. MTB315, launching two torpedoes that passed astern, followed for a time before withdrawing.

Map 12.1 The Italian Armistice, September 1943

All British torpedoes missed, although they claimed a hit, while Scipione took credit for sinking three of the four boats. In fact, MTB260 and 313 were lightly damaged. Scipione made Taranto without further incident at 0940 that morning.

On 22 July Palermo surrendered, and by the 23rd only the island’s northeastern third remained in Axis hands. Sicily’s imminent fall had major political repercussions. On 25 July, King Victor Emmanuel III ordered Benito Mussolini arrested, following a rare meeting of the Italian Fascist Grand Council. The king immediately formed a new government under that ambitious survivor, Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio. Badoglio proclaimed that the war would continue, even as his government tentatively contacted the Allies. The Germans had no doubt that Mussolini’s fall foreshadowed a separate peace and acted accordingly. On 28 July Grossadmiral Dönitz ordered that “if Rome is occupied the German Navy will immediately secure the Italian Fleet units in La Spezia, Taranto, and Genoa . . . the Commanding Officer of Submarines, Italy, shall station submarines off La Spezia making sure, however, that the Italians do not become aware of this. . . . They will destroy the large ships of the Italian Navy if the latter should leave without our approval.”12

Supermarina knew that the new government was sounding out the Allies but continued to mount minor operations, for political as much as military reasons. The Italian liaison officer with the Germans wrote, “The employment of the Navy for offensive missions was the minimum proof of goodwill to continue the war, which the Germans anxiously sought.”13 On 4 August Eugenio di Savoia and Montecuccoli sortied to strike Allied shipping at Palermo. Early on the morning of 6 August, just an hour from their destination, the cruisers encountered the American subchaser SC503 escorting a water barge. The American boat challenged, worried that she had encountered a pair of friendly but trigger-happy destroyers, whereupon both Italian ships opened fire. After three salvos SC503 turned her 12-inch searchlight upon herself, and then upon the enemy, to convey that she was friendly. This had the desired effect, as the cruisers abruptly ceased fire and changed course. The Italians believed they had encountered a corvette leading torpedo boats; the commander, Rear Admiral Romeo Oliva, reported, “At 0434 considering as a result of the encounter with enemy torpedo boats and likely air reconnaissance that the surprise on which the mission depended had been lost. . . . I decided not to proceed.”14

Thinking Oliva had come close to success, Supermarina launched a follow-up raid with Garibaldi and Duca d’Aosta, under Rear Admiral Giuseppe Fioravanzo’s command. These ships departed Genoa on 6 August and staged through La Maddalena the next day. However, as they approached Palermo at 0200 on 8 August, a radar-equipped German aircraft warned of enemy warships near the target. Supermarina ordered Fioravanzo to continue, assessing the sighting as four merchant vessels, but Fioravanzo had already turned away. Had he continued he would have run into the U.S. light cruisers Philadelphia and Savannah and destroyers Bristol and Ludlow. The Regia Marina’s new chief of staff, Admiral Raffaele De Courten, who was half-German and had been the naval attaché in Berlin, sacked Fioravanzo and continued to mount cruiser sweeps from Taranto, mainly to lay mines.

On 17 August, with the conquest of Sicily complete, De Courten decided that when the Allies moved against the mainland the fleet would commit itself in “a heroic gesture for the honor of the nation and the Navy.”15 As Supermarina drew up plans the odds remained poor, but at least Roma had rejoined the fleet, the steaming distance was only 350 miles, and recent exercises had demonstrated the ability to control fighter aircraft from battleships with ship-to-plane radio links. However, on 3 September, still unbeknownst to the navy’s leadership, representatives of General Eisenhower and Badoglio signed an armistice document not only ending Italy’s participation in the Axis but declaring Italy’s intention to cooperate with the Allies. The same day, British forces crossed the Straits of Messina.

That evening Badoglio briefly met the chiefs of staff and advised them that armistice negotiations were under way. He did not reveal that the deal was already done. In part Badoglio based this extraordinary discretion on the advice of General Ambrosio, the plan’s principal architect. Ambrosio hoped that the Germans would, when faced by the deal he had crafted, retreat to the north, that the army or SS would depose Hitler, and that the Third Reich would collapse like the second one had in 1918. Such a scenario would make heroes of Badoglio and Ambrosio and spare Italy a bloody separation from its adamant ally.

However, the scenario did not unfold as the army’s warlords wanted. During the protracted negotiations German troops had been pouring into Italy, and at the last moment Badoglio attempted to delay the armistice. Eisenhower would have none of that, however, and on 8 September, just ninety minutes before the American general went on the air and announced Italy’s surrender, Badoglio informed the king and the navy that an armistice had been signed. Some of the king’s council recommended that Italy renege, but the king confirmed Badoglio’s actions, and shortly thereafter the marshal went on the air and reluctantly affirmed the deal. At that moment, the Regia Marina had in its fleet the major ships listed in table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Status of the Regia Marina, 8 September 1943

At 0500 the next morning Badoglio, Ambrosio, and the king fled Rome without ordering resistance against the Germans as the Allies had expected. Although caught by surprise, Supermarina ceased hostilities and instructed units to concentrate in bases under Italian control, rather than the ports specified in the armistice document. The battle fleet had already raised anchor at 1700 on 8 September to attack the Salerno invasion beaches. De Courten telephoned the fleet commander, Admiral Carlo Bergamini, and convinced him to sail to La Maddalena rather than scuttling, as Bergamini wanted.

Because the king had ordered De Courten to accompany him on his flight from Rome, the deputy chief of staff, Vice Admiral Sansonetti, remained at headquarters, despite the uncertain conditions. The failure to implement a coordinated response to the armistice most impacted Italy’s army, which melted away, but it affected the navy as well. For example, at 0200 on 9 September the Italian 11th Army in Greece signed a truce with the local German command. This included the Italian warships at Piraeus and Suda Bay, which were under its jurisdiction. The order was soon extended to the Albanian base of Durazzo. The warships thus handed over proved useful to the Germans in their forthcoming Aegean and Adriatic campaigns.16

Elsewhere, fighting between the erstwhile allies had already erupted. At Bastia, in Corsica, German navy troops seized the harbor at midnight and damaged the torpedo boat Ardito (slaughtering seventy members of her crew), the freighter Humanitas (7,980 GRT), and a MAS boat. The torpedo boat Aliseo, skippered by Commander Fecia di Cossato, who wore the Iron Cross Second Class and the Knight’s Cross for his successes as a submarine commander in the Atlantic, cast off just in time and was able to slip out of port. Aliseo then stood offshore and awaited instructions.

Italian troops counterattacked early that morning and drove the Germans from their positions. The Italian port commander radioed Aliseo and instructed di Cossato to prevent the German ships from withdrawing. (See table 12.3.)

Table 12.3 Action off Bastia, 9 September 1943, 0700–0845

Conditions: Light mist, calm seas |

|

German ships— |

SC: UJ2203Sunk (2,270 tons), UJ2219Sunk (280 GRT); MFP: F366Sunk, F387Sunk, F459Sunk, F612Sunk, F623Sunk; ML: FL.B.412Sunk |

Italian ships— |

(Commander Fecia di Cossato): TB AliseoD2; DC: Cormorano |

At dawn a light fog hung along the shore. Aliseo’s lookouts saw enemy vessels emerge one by one from the mist at the port’s narrow mouth and swing north, hugging the coast.

The German flotilla was superior to Aliseo in every respect except speed. Both escorting subchasers had 88-mm guns, while each barge was armed with one 75-mm and either a 37-mm or 20-mm gun. Nonetheless, Aliseo closed range as the subchaser UJ2203 opened fire, followed by other German units as they bore. The torpedo boat zigzagged and withheld fire until 0706, when she was eight thousand yards from the German column. Then, for the next twenty-five minutes, she ran north paralleling the German line and firing rapidly. At 0730 an 88-mm shell hit Aliseo in her engine room. Emitting a great cloud of steam she drifted to a halt, but her crew rapidly repaired the damage and plugged the holes to minimize flooding, and she was able to get under way.

Renewing the action, Aliseo overhauled the German formation by 0815 and turned west, quickly closing the enemy. The shorter range improved her accuracy; 3.9-inch shells slammed into UJ2203 and several of the barges. At 0820 UJ2203 exploded, killing nine men and sending an enormous column of smoke into the air. Aliseo shifted her fire to UJ2219, and ten minutes later she too exploded and sank.

Meanwhile, the column of motor barges, maintaining an intense fire, began to break up as each craft fled on its own. Machine-gun shells riddled Aliseo’s fire-control director, forcing her guns to continue under local control. But with the ranges nearly point-blank, this hardly mattered. “The Captain continued to maneuver to shorten the range. We locked onto a group of three motor barges. We were so close we were able to duel with machineguns. We were hit profusely with 20 mm projectiles, but they failed to inflict serious damage.”17

By 0835 Aliseo had sunk three barges. At 0840 she engaged two more, which were loaded with ammunition. These boats were being shelled by Italian shore batteries at Marina de Pietro and by the Italian corvette Cormorano, which had just arrived. Caught three ways, they ran themselves ashore.

With ammunition nearly expended, Di Cossato ceased fire at 0845. Between 1000 and 1050 Aliseo pulled twenty-five Germans from the water, but 160 lost their lives. Di Cossato then set a course for La Spezia until ordered instead to Elba, arriving there that afternoon.

In other clashes, German artillery sank the Italian minelayer Pelagosa off Genoa and the corvette Berenice off Trieste.18 The incomplete cruiser Giulio Germanico repulsed an attempt by German troops to seize the town of Castellamare di Stabia in the Gulf of Naples. However, the most serious event occurred at La Maddalena, where German commandos attacked the naval base at noon on 9 September and captured the commander, Rear Admiral Bruto Brivonesi, of Beta convoy fame. This left no Italian-controlled port in the western Mediterranean capable of receiving the battle fleet.

At 1225, off Cape Santa Maria di Leuca, in southern Puglie, S54 and S61 with the barge F478 sank two Italian auxiliary minesweepers. At 1430 Scipione arrived and forced the German motor torpedo boats to scuttle the MFP and flee.

At Rhodes Italian forces captured the German steamship Taganrog. German R-boats clashed with the Italian submarine chasers VAS234 and 235 off the Gorgona Islands. Near Terracina the corvettes Folaga, Ape, and Cormorano engaged five German MFPs, sinking F345 and forcing the other four ashore. At Castiglioncello, German minelayers eliminated two Italian auxiliaries and captured the minelayer Buffoluto after a long gunfire exchange.

Then, at 1535, twenty-eight Do.217 bombers armed with the recently introduced FX-1400 guided bomb attacked the battle fleet, sinking Bergamini’s flagship Roma, killing nearly fourteen hundred men, including the admiral, and lightly damaging her sister, Italia (the former Littorio). At the same time Duilio and Doria, the cruisers Cadorna and Pompeo, and the destroyer Da Recco departed Taranto. Originally believing the Germans intended to occupy the port, Vice Admiral Da Zara planned to scuttle his squadron, but the area commander convinced him to sail instead for Malta and, as long as the ships remained under Italian control, to respect the armistice.

Clashes between the Regia Marina and German forces continued. At 1650 the destroyers Vivaldi and Da Noli attacked a German R-boat and three MFPs in the narrows between Corsica and Sardinia and drove the barges ashore. The shore batteries at Bonifacio, which Italian Blackshirts had turned over to the Germans that morning, counterattacked and damaged both destroyers. Da Noli then ran into a mine and sank. A German bomber hit Vivaldi that same day, and she foundered on 10 September.

That night, navy-manned coastal batteries at Piombino sank three German MFPs from a force of ten after their embarked troops attacked the port. The next day the German torpedo boats TA9 and TA11 seized four Italian subchasers that were entering Piombino Harbor. At 2045, TA9 and TA11 attacked the Italian shore batteries. The guns returned fire and sank TA11, the four subchasers, and the ex-French steamer Carbet (3,689 GRT). TA9 escaped heavily damaged and was paid off (that is, taken out of service) later that month.19

On 10 September at 0930 Da Zara’s force appeared off Malta and entered Grand Harbor. That same morning the reduced battle fleet, now under the command of the 7th Division’s Admiral Oliva, came in sight of a British force that included Warspite, Valiant, and seven destroyers. A destroyer carrying Admiral Cunningham and General Eisenhower met the Italian fleet off Bizerte at 1500. After requesting permission, Captain T. M. Brownrigg of Cunningham’s staff boarded the new flagship Eugenio. Eisenhower’s naval aide noted that “as Brownrigg and Smith were seen to board [the cruiser] and all appeared serene, the tension was relaxed, and from gun turrets came smiles and cameras.”20

The battle fleet entered Malta on the morning of 11 September. Admiral Oliva rejected another suggestion by his second in command to scuttle the fleet in Grand Harbor. That afternoon Cunningham and Da Zara, the senior Italian officer present, met; the British admiral’s courtesy to his ex-enemy gratified the Italians. That evening, however, Cunningham sent his oft-quoted dispatch, “Be pleased to inform their Lordships that the Italian Battle fleet now lays at anchor under the guns of the fortress of Malta.” This signal failed to mention that the ships remained armed and under Italian control. In fact, three days later Cunningham wrote in a letter that “[the Italian fleet] is alright at the moment but I smell trouble coming. I am quite convinced that all the ships are prepared to scuttle should things not be to their liking.”21

Meanwhile, another Italian fleet was at sea without a port to enter. This was a group of corvettes and torpedo boats nicknamed La Squadretta, or little fleet. It had originally headed for Elba, but when events drove it south, Supermarina ordered it to make for Palermo. It arrived there at 1000 on 12 September, much to the surprise of the American commander, who signaled, “Be pleased to inform Their Lordships that Palermo lies under the guns of an Italian Fleet.”22

The most notable aspect of the actions of the individual Italian commanders is that they were ignorant of the armistice conditions and did not enjoy Supermarina’s guidance, which made its last broadcast at 1709 on 10 September, after the authorities in Rome came to terms with the Germans. In this light there was a surprising degree of cooperation between the castaway admirals at Malta and the Allied authorities. For example, the destroyers Legionario and Oriani left Malta on 13 September to transport munitions and an American OSS detachment from Algiers to Ajaccio, Corsica, to assist French and Italian troops fighting there.23

Small-scale actions between the Germans and Italians continued, although at a lower intensity. Major losses suffered by the Italians included the gunboat Aurora, the motorship Leopardi, crowded with hundreds of civilian passengers, and the steamer Pontinia, captured by S54 and S61 on 11 September. These resourceful S-boats then ambushed the destroyer Sella, emerging from behind Pontinia’s lee, torpedoing her from only ninety yards. Their report tersely stated, “One minute later sank without trace. Steamer under command of prize crew was left to pick up survivors.”24 On 14 September a German air attack badly damaged the torpedo boat Giuseppe Sirtori off Corfu. In the Adriatic the torpedo boats Stocco, Sirtori, and Cosenz, as well as some freighters, tankers, and minor vessels, fell victim to German aircraft on 24, 25, and 27 September, respectively. Still, the Regia Marina rescued twenty-five thousand Italian troops from the Balkans during September without Allied support. In the two weeks between 11 and 23 September, Italian forces sank eight German MFPs and seven small auxiliaries.

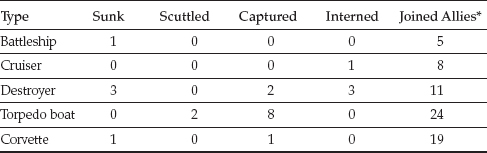

The Italian navy’s core remained intact despite the lack of national direction, the fluid and dangerous situation, and the mixed feelings, if not loyalties, of many officers and men. Finally, on 23 September, Admiral De Courten and Admiral Cunningham signed an agreement at Taranto that provided for naval cooperation between the kingdom of Italy and the United Nations. Table 12.4 indicates the fates of the fleet’s operational units during this period.

Table 12.4 Fate of Italian Units after the Armistice

* includes some vessels under repair

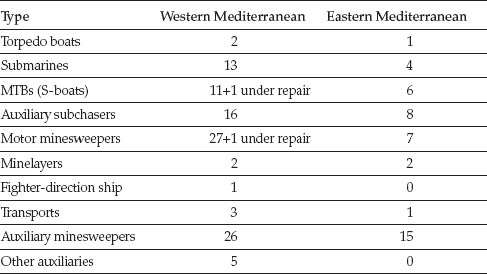

It might have seemed that the armistice would end significant naval combat in the Mediterranean, but this did not happen. Hitler, after some doubts and against the advice of many of his military advisors, concluded that Germany needed to become a Mediterranean power, and so the Kriegsmarine improvised a naval force to supplement the light forces—eighty-eight MFPs, ten Siebel ferries, and fifty smaller landing craft already based throughout the Mediterranean.

The German occupation of so many Italian bases and shipyards had resulted in a windfall of captured vessels, although, with the exception of the old torpedo boats and destroyers handed over in the Aegean, most required considerable work before they could serve. These warships were to form the backbone of Germany’s ongoing resistance in the Middle Sea. (See table 12.5.)

Even after the accord of 23 September, the Allies distrusted their former enemy. In part this was the residue of thirty-nine months of active enmity and propaganda; in part it was caused by the fact that some Italians, including naval units, chose to fight alongside the Germans. Vittorio Veneto and Italia rusted in the Suez Canal’s Bitter Lakes from 19 October 1943 until 5 February 1947 as hostages to Italy’s conduct. The cruisers Abruzzi and Duca d’Aosta, on the other hand, sailed to Freetown, Sierra Leone, on 26 October 1943. From there, joined later by Garibaldi, they searched the central Atlantic for German raiders and blockade runners until March 1944.

Table 12.5 German Navy Deployment in the Mediterranean, 9 September 1943

Type |

Western Mediterranean |

Eastern Mediterranean |

Torpedo boats |

2 |

1 |

Submarines |

13 |

4 |

MTBs (S-boats) |

11+1 under repair |

6 |

Auxiliary subchasers |

16 |

8 |

Motor minesweepers |

27+1 under repair |

7 |

Minelayers |

2 |

2 |

Fighter-direction ship |

1 |

0 |

Transports |

3 |

1 |

Auxiliary minesweepers |

26 |

15 |

Other auxiliaries |

5 |

0 |

Some Regia Marina destroyers patrolled the Albanian and Greek coasts engaging German shore batteries and MTBs during the spring of 1944. Italian destroyers, torpedo boats, corvettes, submarines, and above all, MTBs, conducted 370 special night missions, landing and recovering commandos, agents, and former prisoners of war along the Italian and Balkan coasts. During these dangerous patrols the navy lost a submarine and five MTBs.

The Allies appreciated Italy’s naval special forces. Although X MAS had operated as the major unit of Mussolini’s navy, a Royal X MAS conducted operations, both alone and in conjunction with British forces. The most noteworthy, at least in terms of propaganda value, were the destruction of the hulked heavy cruiser Bolzano at La Spezia on 22 June 1944 and an attack against the carrier Aquila at Genoa on 19 April 1945.

The principal activity of the Regia Marina during the war’s last twenty months, however, was escort duty. “Italian ships almost exclusively performed the duties of protecting and escorting the convoys bringing supplies to the Anglo-American armies in Italy.” Italian ships “carried out 2,644 escort missions for 1,525 convoys made up of 10,496 ships.” Italian cruisers and destroyers also logged nearly 370,000 miles as fast transports, carrying 317,000 men.25

Finally, one of the major activities of the Italian navy consisted of training other Allied forces. Because of their experience, Italian submarines in particular made excellent “aggressors” in exercises. At one time or another, four cruisers, five destroyers, six escort vessels, and forty submarines participated in these activities in the Mediterranean, Atlantic, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean.