It is only the politicians who imagine that ships are not earning their keep unless they are madly rushing about the ocean.

—Admiral Pound, 28 December 1942 letter to Admiral Cunningham

Flawed assessments and disappointed expectations set the early course of the Mediterranean conflict. In June 1940 Great Britain correctly appreciated that it was engaged in a war to the death against the Axis and advertised this fact to the world when it attacked the French at Mers-el-Kébir. London erred, however, when it also concluded there was a quick solution to the conundrum presented by Italy’s entry and France’s exit from the war, and that that was to knock Rome out with a hard blow delivered by the only weapon it possessed for the job, the Royal Navy. Naturally, Italy’s appreciation was much different, although equally wrong. Rome believed it had entered a short war, a holding action really, and did not grant the battle Britain sought but instead tried to fight its own actions, appropriate to the war it wanted to wage—actions in which it would have many advantages and few risks. Neither got what it wanted.

The bitter naval war that ensued demonstrated the tactical application of sea power and its relationship to both the land war and grand strategy. It demonstrated that any nation waging war in the Mediterranean littoral had to use the sea and dispute the enemy’s use to the best of its abilities. This may seem obvious when North Africa was the battleground and supplies could only come from over water, but it was just as true when the Italian and Balkan peninsulas became seats of war in 1943. The unfolding of the naval war demonstrated that to use the sea, combat had to be accepted—generally on the enemy’s terms—but that even so, sea denial was a difficult task and lasting victory came only through the exercise of sea control. Because Italy lacked the long-range warships and airpower required to dispute Allied domination of the Mediterranean’s western and eastern basins, and because the Allies lacked the staying power to routinely break Rome’s blockade of the central basin or to sever the sea lanes to Libya, neither side could decisively exercise sea control in the enemy’s waters. Thus the North African fighting dragged on for three years—longer than any European land campaign of World War II, save the Russian conflict. Then, after the Italian armistice, Germany fiercely defended its Mediterranean bridgeheads to gain time to bring its secret, war-winning weapons on line, or for a Fredrick the Great–type miracle to occur, effectively using the Aegean, Adriatic, Tyrrhenian, and Ligurian seas and prolonging the maritime campaign to the war’s end.

More surface actions were fought in the Mediterranean by more participants than anywhere else in the war (see table C.1).

Table C.1 Surface Engagements by Ocean/Sea

Atlantic (including English Channel) |

49 |

Arctic |

8 |

Baltic & Black |

5 |

Indian |

14 |

Pacific |

36 |

Mediterranean (including Red Sea) |

55 |

The surface engagements described in this work were fought by the nations given in table C.2.

The loss of major surface warships (from battleships to large escorts) to enemy action provides one way to measure performance. The Italians sank thirty-three Allied warships and lost eighty-three in the Mediterranean and Red seas from 10 June 1940 through 8 September 1943 (seventy to the British and their allies and thirteen to the Americans). In this period German forces sank an additional forty-three Allied warships. The warships sunk by Italy totaled 145,800 tons and by the Germans 169,700, for a total of 315,500. The British dispatched 161,200 tons of Axis warships and the Americans 33,900, for an Allied total of 195,100.1

Table C.2 Surface Engagements by Belligerent

Great Britain |

50 |

Italy |

36 |

France |

|

Marine Nationale |

1 |

Vichy |

7 |

Free French |

1 |

Germany |

11 |

United States |

3 |

Greece |

2 |

Australia |

9 |

New Zealand |

2 |

Netherlands |

2 |

The Germans accounted for 57 percent of Allied losses, whereas the British, with minor help from the Polish, Greek, and Dutch navies, accounted for 83 percent of Italian warship losses. German aircraft and submarines proved more effective than their Italian counterparts. German aircraft sank 30 percent of the Allied total loss, compared to only 9 percent for Italian aircraft. German submarines sank 21 percent, compared to 7 percent for Italian submarines. In the categories of special weapons, surface actions, mine warfare, shore batteries, and capture, the Italians accounted for 28 percent of the Allied total, compared to 5 percent for the Germans.

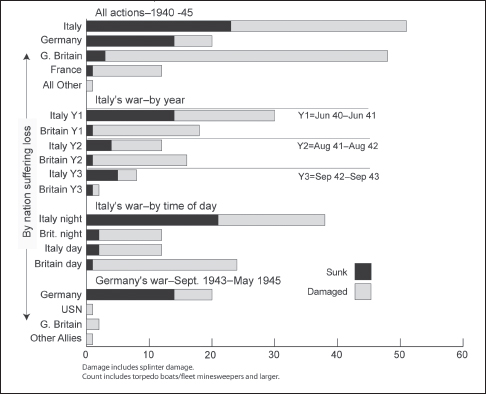

The differences in the Italian and German tallies suggest certain conclusions. First, the Regia Aeronautica did not develop the weapons and tactics needed to participate adequately in the naval war. Had the Regia Marina controlled its aerial assets and developed an efficient reconnaissance force and the torpedo-bomber squadrons envisioned in the mid-1930s, Italy would have fought more effectively at sea. Next, Italian submarines were less deadly than their German counterparts mostly because of unrealistic training and flawed doctrine. Finally, while the Italian navy suffered more damage in naval surface actions than it inflicted, the vast majority of this damage was incurred at night, in a few actions fought in defense of traffic. Chart C.1 further illustrates this point.

Allied warships were more effective ship killers than were Italian or German vessels. British warships accounted for twenty-three major Italian and nine German warships, while the U.S. Navy sank two Germans and the French one.

Chart C.1 Ships Sunk and Damaged in Surface Actions, 1940–45, Mediterranean and Red Sea

The Royal Navy only lost three major warships—all destroyers—as the result of Italian surface action (excluding a cruiser and three destroyers sunk by Italian and German MTBs). The difference revolved around when the action was fought. The British nighttime superiority was based upon better training and doctrine, radar, and an ability to pick the time of action and so achieve surprise. Moreover, the Regia Marina achieved dismal results with its ship-launched torpedoes due to inferior doctrine, training, and fire control.

Italian performance, however, improved as the war progressed. The Regia Marina inflicted more damage than it suffered during the war’s second year, and it fought effectively during the day when sea control was exercised, sinking one and damaging twenty-three British ships while suffering two sunk and ten damaged. Finally, while many factors affected German effectiveness in surface actions fought following the Italian armistice, the final tally—fourteen large German warships sunk and six damaged versus the light damage Kriegsmarine vessels inflicted on four Allied warships in return—reflects favorably on Italian performance in the same type of nocturnal clashes in defense of traffic.

The Regia Marina survived as an effective force, unlike the other Axis navies. That the kingdom of Italy sought an armistice instead of fighting to the bitter end helped, but the fact remains that after thirty-nine months of war Italy still possessed a significant fleet capable of intervention, and that fleet was still running convoys to the islands and along the coasts. When the Ligurian-based battle squadron received the unexpected news of the armistice on 8 September, boilers had been fired and the fleet was prepared to expend itself on a do-or-die strike against the Salerno landings.

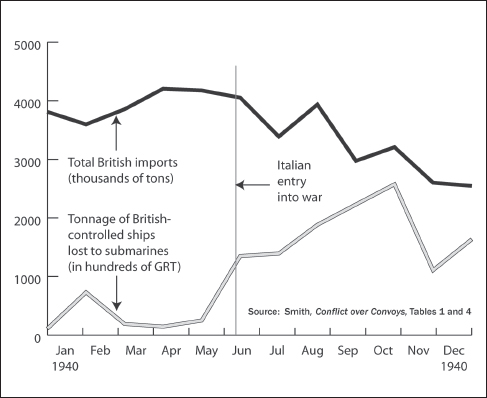

The Regia Marina not only survived but largely accomplished its missions. Up until May 1943 it closed the direct passage through the Mediterranean to all but eight freighters in three massively protected convoys (Collar, Excess, and Tiger, between November 1940 and May 1941). This forced Great Britain to build and supply an army in Egypt the hard way, around the Cape of Good Hope, rather than though the Straits of Gibraltar—a journey of forty days for a fast convoy, and 120 days for a slow one. The tying up of shipping and naval resources by this and the Mediterranean campaign itself had two direct and measurable outcomes. Britain’s imports collapsed and never recovered, while German submarines ran wild.2 (See chart C.2.)

Chart C.2 Impact of the Mediterranean Strategy, British Imports and Tonnage Lost

Chart C.3 Personnel and Materiel Escorted or Carried by the Regia Marina, June 1940–8 September 1943

With regard to Italy’s mercantile war, the chart C.3 demonstrates that over the course of its war, 98 percent of the men and 90 percent of the material that set forth from Italian ports for Libya, Tunisia, or the Balkans arrived safely.

The nature of its operations and the priorities set by the navy’s political leadership required the Regia Marina to operate in a defensive posture defending these convoys in an environment where air support, doctrine, technology, and intelligence favored the Allies. Italy’s navy certainly had its failures and suffered its defeats. But these should not obscure its victories. Overall, it performed the jobs it was tasked to do. It was a successful service, considering its lack of oil or of an integral air component and the caliber of the opposition it faced.

In 1939 the Marine Nationale was the world’s fourth-largest fleet, equipped with modern and innovative warships. After France’s defeat the navy remained intact and served as the Vichy regime’s principal expression of power and prime guarantor of its precarious independence. When Germany occupied Vichy France, the heart of the navy destroyed itself, out of loyalty to its unique and powerful sense of honor. During the balance of the war the Marine Nationale’s remnants served the Allied cause. It is significant that when the navy, in any of its avatars, had an opportunity to fight, it fought well. It beat the British off Syria and Dakar and the Germans in the Adriatic, and it earned the grudging admiration of its opponents, even in defeat off Oran and Casablanca.

Such devotion to what the British, Americans, and even the Germans considered an unworthy cause demonstrated that if French motivations remained mysterious to friend and foe alike, they were strong enough to endure the motherland’s defeat, its occupation, and more than two years of political twilight. Many writers describe the Vichy French government as collaborationist or traitorous, which implies that it was bound to act in Britain’s interests. Pétain, however, regarded France’s welfare as paramount. The key to evaluating the French navy’s performance and resilience is to appreciate that France acted, always, in what it perceived to be its own best interests. The situation from June 1940 to the end of 1942 left little space for defying the Germans. The most remarkable aspect about the French navy during the Vichy period is that it did not become an Axis cobelligerent, despite British provocation and German pressure. This fact demonstrated where France saw its own true interests to lie.

The Royal Navy’s deeds in the Mediterranean fill a proud chapter in that service’s glorious history. The Beta Convoy battle, the action off Sfax, the Battle of Cape Bon, and the action off Skerki Bank were some of the most aggressive and successful surface actions ever fought. Individual ships like the light cruiser Aurora compiled records that would be the envy of any warship, at any time, in any service. The irony, however, is that despite these examples of excellence and the Royal Navy’s superiority in intelligence, doctrine, technology, and resources, London, when it adopted its Mediterranean strategy in the summer of 1940, chose a campaign the navy was unable to win.

Wars are complicated processes, with subtle interconnections that defy easy analysis; however, by this strategic decision Britain beggared itself fighting what turned out to be a three-year-long war of attrition at the end of a supply line that ran twelve thousand miles around Africa. The Royal Navy’s victories were mostly in sea denial, not the sea-control victories it required. Nor did American intervention break the deadlock. After an inconclusive, three-year seesaw campaign in Libya and Tunisia, the Allies required four major amphibious operations to advance the front line gradually across the Mediterranean and partially clear its northern shores. The war in the Middle Sea lasted fifty-nine months; by contrast, in northern Europe the Allies thrust from Normandy into the heart of Germany in just ten months. When the Soviets raised the red flag on the Reichstag on 1 May, a stubborn trickle of German shipping still plied the Middle Sea. When troops of the U.S. Fifth Army finally reached the Brenner Pass—the Mediterranean Theater’s northern frontier—on 6 May 1945, they discovered that their comrades of the Seventh Army had already driven through Germany and had arrived there two days before them.

The Kriegsmarine fought thirteen surface actions in the Mediterranean between 9 September 1943 and 2 May 1945, and while it avoided defeat in two instances, it failed to win a single victory. In fact, the Germany’s record of defending convoys in night actions was worse than Italy’s. However, Germany did not have to rely upon do-or-die convoys, as Italy was forced to at certain points in the war. The narrow waters permitted the Germans to conduct a guerrilla war, and the Allies, despite all the resources at their disposal, never eliminated German maritime traffic. Given the technology of the time, perhaps it was impossible to stop a determined foe who was willing to accept losses. In any case, the Kriegsmarine did what was required—it fought a littoral war, shielded against a landing in Istria and Liguria that would have cut off the Reich’s Italian army, and sustained a vital maritime traffic, as well as its island garrisons. It survived in the Middle Sea until the end of the war, despite overwhelming Allied naval and air power and, in so doing, was instrumental in preventing the Reich from ever being threatened from the south.

The U.S. Navy was the last major force to enter the theater. Its efforts are commonly associated with the Pacific, the war against shipping in the North Atlantic, and the cross-channel invasion; however, its Mediterranean commitment was large. Including the Torch operation, the USN participated in five major amphibious landings. The American convoys that transited the Mediterranean after 1942 dwarfed in size everything that had come before. In addition, by lending warships to the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet the USN allowed Great Britain to release ships for its Mediterranean operations in the summers of 1942 and 1943.

By May 1945 the U.S. Navy, despite massive forces deployed in the Pacific and heavy commitments in the Atlantic, was the Mediterranean’s dominant naval power, and it has remained so ever since.

In summary, the Italian navy fought hard, and overall it fought well; the French demonstrated resolve and honor and proved a formidable foe when occasion forced it to fight. The British were workmanlike at their worst and brilliant at their best, but their focus on the Mediterranean was a strategic mistake that worked to Germany’s benefit until the last day of the European war. The Germans conducted a remarkable and seldom-recognized rear-guard action and defied Allied attempts to deny them use of the Middle Sea. The Americans came to the Mediterranean late, but they ultimately came in great strength, though unfortunately, in their choice of amphibious objectives, they did not display the strategic boldness they had demonstrated in the Pacific campaign.

Nearly seventy years after Italy declared war, giant tankers and container ships ply the Mediterranean. What has changed since 1940 is that the economies of the littoral states are even larger. Egypt minds the Suez Canal, and Malta is independent, but Great Britain still possesses Gibraltar and bases at Cyprus. There has been conflict on the Middle Sea since 1945. Great Britain and France attacked the Suez Canal in 1956, and France warred in Algeria. The United States struck Libya in 1982 and 1986. Israel and its neighbors have fought four general wars, which included several naval battles. American, British, and Italian warships and submarines stalked their Soviet counterparts for fifty years, never crossing the threshold into open conflict. Meanwhile, as always, the Marine Nationale largely went its own way.

Today, the Middle Sea remains one of the planet’s decisive choke points. Despite the end of the Cold War, it is crowded with warships from many nations. Although it is hard to imagine the circumstances that could result in another major naval war, the possibility remains as long as the region is so well armed and all the Mediterranean nations have so much at stake in their free use of the sea.