“AS YOU MAY IMAGINE,” the President wrote his Uncle Fred Delano on July 18, “the events of the past few days have filled me more with a sense of resignation to my fate than any feeling of exaltation.” Expressing to Norris his amazement at the conservatives’ “terrific drive” to produce a situation in the convention that would force him to decline the nomination, the President ended, “even though you and I are tired and ‘want to go home,’ we are going to see this thing through together.”

Roosevelt could feel well satisfied with the final results of the convention. He had soundly drubbed the conservatives, including many of the anti-Roosevelt men who had been thwarting him ever since the Supreme Court fight. The platform was a stout defense of the New Deal. He had secured a running mate who was, as he said to Norris, a “true liberal.” He had gained for himself the draft he needed. Broadly speaking, his tactics of delay and indirection had worked. As the first ballot tally showed, no strong candidate had been left to threaten him. The opposing forces had never got together. He had beaten “The Hater’s Club,” made up, he told Norris, of “strange bedfellows like Wheeler and McCarran and Tydings and Glass and John J. O’Connor and some of the wild Irishmen from Boston.” His trump card—keeping open the possibility of declining the nomination until the very end—had paid off handsomely.

On the other hand, Roosevelt had lost the thing he wanted most—an unquestioned draft by acclamation. Farley and the others had spoiled the stage effects for a clamorous and categorical summons by the party. The situation had its irony. Roosevelt’s nomination was truly a draft in the sense that the impetus toward his nomination had come not from himself but from the administration and party leaders, and his own efforts had been indirect. But his very attempt to forego leadership brought about a chaotic convention situation in which leadership fell into Hopkins’ hands simply because he was believed to hold the credentials from the President. In the eyes of many delegates Hopkins was Roosevelt’s cat’s-paw. The forced nomination of Wallace completed the picture of a White House dictatorship over the party.

The price of victory was steep. Hundreds of delegates left Chicago for home in a bitter and rebellious frame of mind. Feeling against Wallace was so strong that he had to be dissuaded from delivering an acceptance speech at the convention. Party leadership was shaken. Farley was determined to quit the chairmanship. Other party regulars—notably Flynn—would not assume leadership unless Hopkins was sidetracked. Ickes, McNutt, and other administration leaders were hurt and angered by the President’s selection of Wallace. Bankhead was telling people how Roosevelt men had sold him out at Chicago. Garner prepared to pack up and go home to Texas for good.

Republican newspapers gleefully headlined a flurry of anti-third-term Democrats who bolted the Roosevelt-Wallace ticket in the wake of the convention. Some of these had deserted their party in 1936, but they made fresh copy again four years later. The newspapers also played up the convention as a packed New Deal caucus manipulated by White House stooges, radicals, city bosses, and the “voice from the sewer.” The press, of course, was heavily anti-Roosevelt. Yet the President was vulnerable. The show in Chicago had not quite come off: he had won his draft in such a way as to intensify popular suspicion of his deviousness. It was not surprising that polls showed a Republican resurgence. The parties, according to some polls, were entering the presidential battle on even terms.

The President’s main trouble, though, lay in none of these, but in a big, shaggy man who, during the late July lull, was busy pumping hands and visiting rodeos in Colorado. A glittering new figure had emerged on the political scene.

Legends were sprouting profusely around Wendell Willkie by midsummer 1940, but the facts were striking enough. Born in 1892, the fourth of six children, he was descended from Germans who had left their homeland after the revolutionary disturbances earlier in that century. He grew up in Indiana amid an intellectually and politically fertile family; his father was a teacher, lawyer, and Bryanite Democrat, his mother a lawyer and a gifted public speaker. After stints at teaching, law, and the army, young Willkie spent ten years in Akron as a lawyer-businessman, then moved to New York City in 1929, where he made a meteoric rise in the utilities field. In January 1933, a few weeks before Roosevelt’s first inauguration, he became head of the huge Commonwealth and Southern Corporation.

During the next seven years Willkie became the most articulate and effective business critic of the New Deal. Scorning Liberty League tactics, he shouted his denunciations from hundreds of platforms across the country and in scores of magazine articles. He sold himself as the chief victim of the New Deal, as an honest, enterprising businessman overwhelmed by big government. He had, indeed, been beaten time and again by the New Deal—beaten in his attempts to hold off the TVA, beaten in his fight against the “death-sentence” clause of the public utility holding company bill, beaten in his campaign efforts for Landon, beaten finally in the courts. It seemed a monumental piece of poetic justice that now he could take on, in direct and open combat, the author of all his misfortunes.

He was the perfect foil for Roosevelt. Like the President, Willkie was a big, attractive man, who liked to talk and to laugh; but the two antagonists were cut from sharply different cloth. Willkie’s touseled hair, broad face and jaw, bulky frame, baggy, unpressed clothes gave him a countrified look that appealed to middle-class America. “A man wholly natural in manner, a man with no pose, no ‘swellness,’ no condescension, no clever plausibleness … as American as the courthouse yard in the square of an Indiana county seat … a good, sturdy, plain, able Hoosier,” Booth Tarkington said in a description that set off the Indianan from the slick figure in the White House.

Inside this rustic form was an urbane New York cosmopolitan. Widely read and traveled, Willkie was literate enough to write book reviews for reputable journals, facile and knowledgeable enough to steal the show on “Information Please,” the phenomenally popular radio program of the day, and versatile enough to win over a wide range of audiences in his vigorous, “man-to-man” talks. He was, a newspaperman noticed, “a master of timing releases, issuing denials before edition time, adding punch to a prepared speech, or making one on the spur of the moment letter-perfect enough to have been memorized, treating publishers, editors, and reporters with the skill needed to suggest to each that they were the sole beneficiaries of his gratitude and his confidence.” Moreover, in seven years of crisscrossing the country in his one-man battle against the New Deal, Willkie had won the friendship of the very publishers—notably Roy Howard and Henry Luce—who had become increasingly alienated from the White House.

From the start Roosevelt saw the Republican candidate as a serious threat. Here was no solemn engineer, like Hoover, no raw novice in national politics, like Landon. Roosevelt had first met Willkie in December 1934. Their talk was friendly, but not their feelings; afterward Roosevelt told how he had outdebated his visitor and reduced him to stammered admissions, while Willkie wired his wife, an anti-New Dealer, CHARM EXAGGERATED STOP I DIDN’T TELL HIM WHAT YOU THINK OF HIM. The President felt that Willkie’s utility background would hurt his opponent’s chances, but the Republican selection for Vice-President of Senator McNary, a long-time supporter of public power and farm aid, was bound to take some of the sting out of any attempt to tie Willkie with the “interests.”

Nor could Willkie himself easily be labeled a reactionary. He had come out publicly for many of the chief New Deal reforms. A bitter and active foe of the Klan during the 1920’s, he had a deserved reputation as a friend of civil liberties. And he was an internationalist who had said, a month before the Republican convention, that “a man who thinks that the results in Europe will be of no consequence to him is a blind, foolish and silly man.” Willkie was as flexible in his views as most other politicians panting for a presidential nomination. But this made him a hard man for the Democrats to label. Indeed, the Indianan himself was a Democratic bolter: he had been a delegate to the 1924 Democratic convention, he had voted for Roosevelt in 1932, and he was calling himself a Democrat as late as 1938.

All in all, Willkie and McNary were formidable opponents—the strongest ticket the Republicans could have named, Roosevelt felt. The nature of the two conventions also strengthened Willkie’s hand. The Republican convention had appeared as open and unbossed as the Democratic had seemed tawdry and rigged. In fact, however, Willkie’s build-up had been spurred by a great deal of money and an avalanche of propaganda; yet his sixth-ballot triumph in the convention over the Dewey and Taft “steam rollers” left him looking like a Galahad.

In mid-August Willkie made his acceptance speech in his home town in Indiana. A colossal shirt-sleeved crowd—a quarter-million strong, some said—stood in a grove in the stifling heat and heard Willkie lambaste the third-term candidate. “Only the strong can be free,” he shouted in his slurred, twangy way, “and only the productive can be strong.” In this speech and in the ones that followed, as his voice turned husky and then hoarse and finally became a scratchy croak, Willkie’s initial strategy became clear. He would accept the major foreign and domestic policies of the New Deal. He would attack Roosevelt on three main counts: seeking dictatorial power, preventing the return of real prosperity, and failing to rearm the country fast enough in the face of foreign threat.

He was eager, Willkie proclaimed again and again, to meet “the Champ.”

The Champ would not enter the ring for a while. Even before his renomination Roosevelt had decided on his campaign tactics in the event he should run again. Spurning ordinary election campaigning, he would stay close to Washington and emphasize his role as commander in chief. He would ignore the opposition. Occasionally he would travel through the eastern states on inspection trips. It would be the tactics of 1936, except that now he would be inspecting defense plants and naval depots rather than PWA projects and drought areas.

“Events move so fast in other parts of the world that it has become my duty to remain either in the White House itself or at some nearby point where I can reach Washington and even Europe and Asia by direct telephone—where, if need be, I can be back at my desk in the space of a very few hours,” he had said in his acceptance speech. “… I shall not have the time or the inclination to engage in purely political debate.”

As usual, the old campaigner had left himself an opening.

“But I shall never be loath to call the attention of the nation to deliberate or unwitting falsifications of fact, which are sometimes made by political candidates.” The effect of this, of course, was that the President could enter the campaign at any moment he chose.

Roosevelt made the most of his role as commander in chief. His defense inspection trips were arranged so that he would pass through as many towns as possible. Presidential aides tried to keep state and local politicians off the President’s train, but the press was given ample opportunity to picture the commander in chief watching army maneuvers and gazing fondly at aircraft carriers under construction. During a defense trip through northern New York the President met with Prime Minister Mackenzie King, and it was agreed to set up a Permanent Joint Board on Defense to consider the security of the north half of the Western Hemisphere.

Vainly the White House correspondents tried during August to get Roosevelt to answer Willkie’s barbed shafts. “I don’t know nothin’ about politics,” he said coyly.

The President’s defense role was not merely a campaign tactic. By midsummer 1940 the nation was feverishly rearming, and quick decisions had to be made in the White House. Roosevelt’s availability was all the more necessary because he had refused to delegate central control of defense production. When he had set up the Defense Advisory Commission at the end of May 1940, one of the members, William S. Knudsen, asked, “Who is our boss?” Roosevelt answered, laughing, “Well, I guess I am!” Administratively, it was a makeshift arrangement, but politically it enabled Roosevelt to keep his fingers on this delicate and vital phase of policy.

Diplomatic developments, too, required close attention. All over the world foreign offices were revising their estimates in the wake of France’s fall. Relations with the new French government were severely strained, and the United States was caught in the middle. The Japanese military, its eyes on the Dutch and French possessions left almost undefended after Hitler’s blitz, won control of the Japanese cabinet in mid-July. An even greater problem involved hemisphere defense, for it was feared that Hitler might now either force France and Holland to cede their Caribbean possessions, or he might seize them by attack or infiltration. Hull brought off a brilliant coup at the Havana Conference late in July by wangling conference approval of his program for opposing transfer of European possessions in the New World, but the situation still bristled with a host of diplomatic and military difficulties.

Despite these formidable problems, Roosevelt never forgot that he had a campaign on his hands. He arranged for Ickes to answer Willkie’s speech of acceptance and watched happily the ensuing Donnybrook as Willkie became involved in answering the pugnacious Secretary’s charges that the Republican nominee had been a member of Tammany Hall and had once eulogized Samuel Insull, the notorious utilities czar. The President also tried to put the creaking Democratic party machinery into shape. Farley, still galled by his treatment at Chicago, remained unwilling to continue as national chairman despite all the persuasion Roosevelt could bring to bear, and Flynn took over the job. Since the Good Neighbor League had been allowed to die, a new organization had to be set up to attract Republicans and independents; Norris and La Guardia, with the help of Corcoran and other administration aides, took on this job. Roosevelt telephoned city bosses direct to make arrangements for his campaign appearances.

It was a time of cabinet reshuffling too. To take the place of Wallace, who was already campaigning quietly, Roosevelt chose Claude R. Wickard, a “dirt farmer,” as Secretary of Agriculture. Hopkins, still ailing, resigned as Secretary of Commerce in order to work directly for the President; by appointing RFC chief Jesse Jones to succeed him Roosevelt rewarded the big Texan for his cooperation at Chicago and also restored to his official family the kind of political balance the President liked, especially at election time. Frank Walker’s appointment as Postmaster General maintained Catholic representation in the cabinet after Farley’s departure, and Stimson’s and Knox’s presence gave the official family a strong bipartisan cast. During the summer two distinguished writers joined Hopkins and Rosenman to work on campaign speeches: playwright Robert Sherwood and poet Archibald MacLeish, whom Roosevelt had made Librarian of Congress the previous year.

This would be Roosevelt’s ninth campaign for office, his third for the presidency. But events would not allow this to be an ordinary campaign.

“The Battle of France is over,” Churchill told a rapt House of Commons in mid-June. “I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilisation. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire.… Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age, made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.

“Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will say, ‘This was their finest hour.’ ”

Four weeks later Hitler informed his generals and admirals: “As England, in spite of the hopelessness of her military position, has so far shown herself unwilling to come to any compromise, I have decided to begin to prepare for, and if necessary to carry out, an invasion of England.” Preparations must be completed by mid-August for this operation, which was given the code name “Sea Lion.” The Fuehrer stressed that success depended on gaining air superiority and then controlling a sea lane across the English Channel for the invaders.

As Hitler marshaled shipping, deployed three crack armies, and mustered his awesome Luftwaffe for the softening up, Churchill again turned to Roosevelt for help. Destroyers, he wrote the President, were vitally necessary to repel the seaborne invasion and to protect Britain’s supply routes. In the last ten days alone, the Nazis had sunk or damaged eleven British destroyers. He must have fifty or sixty of America’s old, reconditioned destroyers at once. The next three months would be vital—if Britain survived this phase it ultimately would triumph.

“Mr. President,” Churchill warned, “with great respect I must tell you that in the long history of the world this is a thing to do now.”

What could Roosevelt do? He was fully aware of the dreadful urgency of the situation, but the political obstacles seemed insuperable. Senator Walsh’s law provided that the President could send destroyers to Britain only if the navy certified that they were useless for United States defense, and naval officials had recently testified as to their potential value so that Congress would not junk them as a drain on the taxpayer. Clearly special legislation would be necessary—and Walsh, Wheeler, Nye & Co. would be waiting with raised hatchets. The President had toyed with the idea of allowing the destroyers to be sold to Canada on condition they be used only in hemisphere defense, thus relieving Canadian destroyers for service off England, but this weak subterfuge he cast aside.

It was not the President but a faction in the cabinet that broke the stalemate. Stimson, Knox, and Ickes were pressing for action. At a cabinet meeting August 2 Knox stated that Britain’s situation was more desperate than ever and he passed on an idea that had been circulating for some time in private circles. This was to grant the destroyers in exchange for military bases on British possessions in the Americas. The idea drew wide cabinet backing. On the question whether Willkie should be consulted the cabinet was divided, but Roosevelt decided to bring him into the picture. The President, still assuming that legislation was necessary for the deal, calculated that Willkie could help line up Republican support on the Hill.

From the cabinet room Roosevelt telephoned William Allen White and asked him to talk with Willkie. White was optimistic—had not the Republican candidate called for full aid to Britain? But when White talked with Willkie in Colorado he found him personally in favor of legislation to send destroyers but unwilling to take a public stand. Willkie’s difficulty lay in the Republican isolationists who dominated his party in Congress. He did not dare arouse this powerful group, including House Republican Leader Joseph Martin, now the Republican national chairman.

“I know there is not two bits difference between you on the issue pending,” White telegraphed the President on August 11. “But I can’t guarantee either of you to the other, which is funny, for I admire and respect you both.”

By now Roosevelt was sorely pressed. For Willkie’s rebuff came just as the Battle of Britain broke over southeastern England. On August 8 two hundred Stukas and Messerschmitts roared down on British convoys. Four days later hundreds more attacked radar stations and airfields. Then the tempo rose fast. On the 13th, 1,400 Nazi aircraft swarmed over England; two days later 1,800, the next day 1,700. This was the Nazis’ “Eagle Attack”—the knockout blow against the Royal Air Force that was designed both to herald and to make possible the invasion.

A cruel dilemma faced the President—the man who hated above all to be forced into a political corner. As Americans heard radio commentators tell of Britain’s ordeal, saw pictures of London burning, of women and children huddling in subways, a wave of sympathy for Britain swept the country. White’s Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, now boasting of six hundred chapters, built up a huge agitation on the destroyer issue. Millions signed petitions; General Pershing, old and ill, pleaded for action before it was too late; newspapers clamored that the President do something.

This same uproar, however, seemed to provoke the isolationists to new virulence. Sale of the destroyers to a nation at war, warned the Chicago Tribune, would be an act of war. By all the measures of opinion the isolationists were in a minority in the country, but, as usual, they were entrenched on Capitol Hill. When Ambassador Bullitt warned that if Britain fell, Hitler would turn on America, senators denounced his speech as an act “little short of treason” by a “multimillionaire, New Deal warmonger.” Roosevelt knew that at best a destroyer bill would drag for weeks through Congress, at worst it would fail, with the awful effect this would have on British morale and on the chances of further American aid.

To make matters worse, Congress was already wrangling bitterly over another contentious matter, compulsory military service. Sponsored by Republican Representative James W. Wadsworth and Democratic Senator Burke of Nebraska, now a hardened anti-New Dealer, the bill was vigorously supported by Secretary Stimson, who was sorely in need of men for his newly forming army divisions. The President had taken no leadership on the bill until August 2 when, under pressure from Stimson and others, he informally came out for “a selective service training bill” in a press conference. His statement produced another explosion on the Hill. Delegations of “mothers” swarmed into congressmen’s offices, religious and labor leaders protested, Senator Wheeler cried that a draft act would be Hitler’s “greatest and cheapest victory,” even Norris said that it would end in dictatorship.

The upshot was that by mid-August the President was committed to a draft bill now stalled in Congress, and, amid frightening reports from Britain, was thinking of sending a destroyer bill to the Hill that would pass too late if at all. In a last-minute essay at the personal influence that had once served so well, Roosevelt wrote Walsh a long, pleading letter. He tried to rebut Walsh’s claims that sending the destroyers would be an act of war, that Americans thought it was too late to commit themselves as the saviors of “surrendered France and Great Britain,” that Hitler would retaliate. It was not time for politics in the ordinary sense, Roosevelt said. But he could not move the Senator from Massachusetts.

What to do? Once again private citizens stepped in at the critical moment. On August 11 there had appeared in the New York Times a long, carefully argued letter showing how the sale of destroyers could be made under existing legislation. It was signed by Charles C. Burlingham, Dean Acheson, and two other distinguished lawyers. The idea of bypassing Congress on the matter was not new to Roosevelt, but this kind of authoritative support could help immeasurably to prepare public opinion for a presidential act. Walsh’s stubborn opposition put the final capstone on Roosevelt’s determination to go ahead on his own.

But now a new set of difficulties loomed. Churchill had always wanted to announce the leasing of bases to America as a spontaneous act separate from the destroyer arrangement. Tying the two matters together in one package, he argued, would make it a kind of business deal, and people would start trying to compute the money value. The embattled Prime Minister doubtless reasoned, too, that the British would consider that they had got the worst of the deal. Roosevelt took just the opposite view. Legally, he could hand over the destroyers only as part of an arrangement that would improve American defenses. Politically, he could win popular support for the measure, he felt, only if he could offer it as a good Yankee deal, so that people would say (in Roosevelt’s later words), “My God, the old Dutchman and Scotchman in the White House has made a good trade.”

For a moment a fatal deadlock threatened. Then Green Hackworth, State Department adviser, came up with an idea. Why not divide the bases into two lots, those in Bermuda and Newfoundland to be leased to America as an outright gift from Britain, the rest to be swapped for the destroyers? Roosevelt eagerly seized on the compromise, and Churchill reluctantly went along. On September 3, with all legal and diplomatic snags overcome, the President announced the deal.

It was barely in time. At the end of August the Battle of Britain was moving toward an agonizing climax. Day after day fagged, red-eyed pilots raced for their planes, rose to engage the invaders, and, if they lived, rose again the next day. Nazi losses were heavy, but the tide of battle was running against Britain’s fighter command. In the fortnight following August 24 nearly a quarter of its thousand pilots were killed or seriously wounded. Airfields were pitted, aircraft factories gutted. Hundreds of German barges were moving down the coasts of Europe to the ports of northern France. On September 3 the German command issued operational schedules for invasion.

But the final order for Sea Lion was never to come. Infuriated by the bombing of Berlin, Hitler turned the weight of his air attack on London and gave respite to the battered fighter command. After that the Luftwaffe could never quite gain mastery of the air. German naval chiefs warned the Fuehrer on September 12 that the British fleet was still in command of the Channel. The invasion date was postponed again and again. On October 12 Hitler shelved Sea Lion until spring.

Just what part the fifty overage destroyers had in the decision to postpone the invasion cannot be known; surely it was a minor factor in the Nazis’ over-all estimate of the situation. Yet it was a factor at a time when the decision on Sea Lion lay in the balance. Even more important, the deal marked decisively the end of American neutrality. The United States was now in a status of “limited war.” The deal came as a jolting shock to Hitler and Mussolini and forced them to consider America more seriously in their global strategy. Late in September the two dictators replied to the destroyer deal by welcoming Japan into a Tripartite Pact; this action, they hoped, would enable Japan to draw America away from Europe and would strengthen American isolationists.

The destroyer deal, too, was a decisive commitment to aiding Britain. It meant that much more military help would follow—as it did. Britain and the United States, Churchill said in Commons, would henceforth be “somewhat mixed up together” in some of their affairs for mutual advantage. “I do not view the process with any misgivings. I could not stop it if I wished; no one can stop it. Like the Mississippi, it just keeps rolling along. Let it roll. Let it roll on—full flood, inexorable, irresistible, benignant, to broader lands and better days.”

For Roosevelt, the destroyer deal was a colossal political risk. He told friends that he might lose the election on the issue. Even more, if England should fall and the Nazis gain control of the British fleet, the President would be fair game for the Republicans, for in that event the fifty destroyers would be turned against their former owner. To be sure, Roosevelt had gained assurances from Churchill that the fleet would not fall in German hands—but who could guarantee the actions of a defeated nation’s government seeking peace? Not only had Roosevelt dared to act—he had acted without Congress.

“Congress is going to raise hell about this,” the President said to Grace Tully as he worked on the draft of the agreement, but, he added, delay might be fatal. He was right. A howl of indignation rose from Capitol Hill. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch published an advertisement in leading newspapers: “Mr. Roosevelt today committed an act of war. He also became America’s first dictator.… Of all sucker real estate deals in history, this is the worst.…” Willkie approved the trade but denounced the bypassing of Congress, which he was soon calling “the most dictatorial and arbitrary act of any President in the history of the United States.”

All this—and the election in two months. Whatever he gained from negotiating the deal—which most voters favored—he might lose from the reaction to his method of bringing it off. Roosevelt knew in advance that bypassing Congress would intensify the popular fear of presidential dictatorship that had bedeviled him for years. Yet he had gone ahead, assumed the responsibility, taken the risk. The President had performed many acts of compromise—perhaps of cowardice—in the White House, especially during his second term. But on September 3, 1940, he did much toward balancing the score. After years of foxlike retreats and evasions, he took the lion’s role.

Churchill had not appealed in vain to the President’s sense of the verdict of history. But Roosevelt wanted vindication on Election Day too.

By the end of September the campaign was taking on an ugly, ominous tone. As he rode through industrial areas Willkie heard workers booing and heckling, saw them spit on the sidewalk and turn their backs. He was showered with confetti in the business and financial sections, but he was pelted with fruit, stones, eggs, light bulbs in the grimy factory areas. Stories circulated about his German ancestry, about signs in his home town reading: “Nigger, don’t let the sun go down on you.” Roosevelt, of course, was not spared either. Besides all the shopworn slanders there were new and ingenious slurs. Leaflets asserted that the combined Roosevelt family had made millions of dollars out of the presidency. When Elliott Roosevelt received an army commission, huge buttons sprouted with the slogan, “Poppa, I wanta be a captain.” SAVE YOUR CHURCH! billboards screamed in Philadelphia, DICTATORS HATE RELIGION! VOTE STRAIGHT REPUBLICAN TICKET!

The President still did not campaign. In mid-September, to be sure, he made an admittedly political speech to the Teamsters Union convention, but he dwelt sonorously on preserving peace and extending New Deal welfare—his hearers would hardly have known that an election campaign was on. Too, he dedicated schools and issued statements on Leif Ericson and Columbus days, but all in his role of chief of state and commander in chief.

Willkie by now was in trouble. The big man, his hair more rumpled, his voice more gravelly than ever, was still drawing big crowds. His difficulty was that he could not find a winning political stance from which to strike out at his elusive foe. At the outset Willkie punched at the New Deal record on two counts: employment and defense. He had a case here: unemployment was still high; Roosevelt had lagged behind rather than led public opinion in national defense measures; sticking to his usual administrative habits, he had not set up an integrated organization for rearmament. But the times were not propitious for an indictment on these counts. The war boom was on: as Willkie spoke in the Northwest, people were flocking back to work in aircraft factories and lumber yards; as he spoke in Pittsburgh the steel mills were humming with new orders. And Roosevelt symbolized the aroused commander in chief. Newspapers and magazines were adorned almost daily with pictures of the President next to big guns, ships, tanks.

Nor did the third-term issue seem to be paying off. Willkie made much of the undemocratic idea of the indispensable man, but here again he could not come to grips with the enemy. Democrats, taking their cue from the President, handled the question by ignoring it. Events abroad, moreover, helped maintain during September the crisis atmosphere in which the voters might find a third term acceptable. The Battle of Britain roared on; Japanese troops moved into Indochina; Italy prepared an attack on Greece.

The Republican challenger also faced divisions within his own camp. Glorifying his amateur support, leaning heavily on the thousands of Willkie Clubs that had sprung up, treating the Republican party as an allied but somewhat alien power, he had antagonized some of the professional organization men at the start. Willkie made things worse by accepting the substance of the New Deal and, on some issues, taking a more internationalist position than Roosevelt. Just a “me-too” candidate, the professionals grumbled. And they pointed to the public opinion polls as proof that such soft campaign methods were not working.

Roosevelt himself helped Willkie decide to reassess his tactics. The President had been stung by Willkie’s assertions earlier in the campaign that the “third-term candidate” at the time of Munich had telephoned Hitler and Mussolini to sell Czechoslovakia down the river. To a press conference early in October the President brought a New York Times dispatch from Rome reporting that the Axis hoped for Roosevelt’s defeat. He would not comment. “I am just quoting the press at you,” he said archly.

Late in September Willkie shifted tactics. Roosevelt now was not an appeaser but a warmonger. “If his promise to keep our boys out of foreign wars is no better than his promise to balance the budget,” he proclaimed in a voice that had acquired the low flat tone of a bass horn, “they’re already almost on the transports.” Sensing that at last he had a winning issue, Willkie went from extreme to extreme.

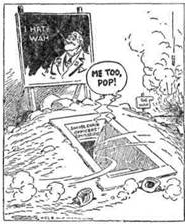

“WARMONGER!”, drawn after Roosevelt sent a message to Hitler on April 18, 1939, David Low, Europe Since Versailles, Penguin Books, 1940, reprinted by permission of the artist, copyright © Low All Countries

BOMBPROOF SHELTER, Oct. 9, 1940, Carey Orr and D.L.B., Chicago Tribune

A REPORT FROM THE OLD DOMINION, Aug., 1941, Fred O. Seibel, Richmond Times-Dispatch

The President seemed all the more vulnerable to such attack because of the passage of the Selective Service Act in mid-September. Backed by both presidential nominees, the act was a special embarrassment to the President because registration day was set for October 16, and the first drawing of lots for October 29, just a week before the election. Despite hints that a delay until after the election might be the better part of discretion, Roosevelt faced his task without flinching. He took symbolic as well as actual leadership of the “muster,” as he preferred to call it, speaking movingly to the nation on registration day and presiding magisterially at the first drawing from the goldfish bowl.

By mid-October, Willkie’s cries of warmonger were sending tremors of fear through Democratic ranks. This was the one great, violent, unpredictable issue. The fear of war had a hysterical tone that seemed to spread to the whole campaign; it was solidly buttressed, moreover, by resentment at the administration among German- and Italo-Americans. Republican orators did not allow the latter to forget Roosevelt’s stab-in-the-back remark. Flynn sent in alarming reports on Italian sections of the Bronx, and Germans could turn the balance in the Midwest. Worrisome stories also reached the White House about the “Irish” isolationist vote; in Massachusetts, Senator Walsh was campaigning for re-election on an isolationist and almost anti-Roosevelt platform.

Newspaper opposition to the President was even stronger than in 1936. Roosevelt’s old friends Roy Howard, Henry Luce of Time-Life-Fortune, and Joe Patterson of the New York Daily News came out against the third term. These publishers Roosevelt long before had written off, but he was surprised when the New York Times announced for Willkie. Roosevelt dismissed the Times editors as merely “self-anointed scholars” in a letter to Josephus Daniels, but he was hurt by the switch of this newspaper that had appeal for independent voters in the East.

Most upsetting of all were the public opinion polls. During September they had shown Roosevelt comfortably leading Willkie. The President, however, was disturbed as well as pleased by these figures. He feared that the final polls might show Willkie gaining and give the impression of a horse race with his adversary likely to pass him just before the tape. Roosevelt even speculated to Ickes that if George Gallup, the head of the American Institute of Public Opinion, ever wanted to sell out, this would be his best chance; Gallup could deliberately manipulate the figures to hurt the Democrats and arrange to sell his business for a good round sum. Roosevelt was wrong about Gallup but he was right about the next poll returns. Influenced by Willkie’s cries of warmonger and by a lull in the Battle of Britain, among other things, the October returns showed Willkie rapidly cutting down the President’s lead.

This shift was all that was needed to put the Roosevelt camp into a state of near panic. For weeks letters and telegrams had streamed into the White House urging the President to come out of his corner and fight; now the stream rose to a flood. With a single voice the party turned to its leader with a cry for help. Ickes haunted the White House pleading that the fight was lost unless the President acted. Deeply angered by Willkie’s campaign Roosevelt on October 18 announced that he would answer the Republican “deliberate falsification of fact” in five election speeches. He passed out word that his lieutenants could go after Willkie with their bare hands.

“I am fighting mad,” Roosevelt said to Ickes.

“I love you when you are fighting mad, Mr. President,” the old gamecock replied.

No commander has ever sized up the terrain more shrewdly, rallied his demoralized battalions more tellingly, probed the enemy’s weak points more unerringly, and struck more powerfully than did Roosevelt against the Republican party during the climactic two weeks before the election. Nor has any commander taken more satisfaction in the job. For it was Roosevelt’s supreme good fortune that the circumstances of the election had brought together, in a sorry alliance, the reactionaries, the isolationists, the obstructionists, and the cynical laborites and left-wingers who had bruised and cut him for four years—all now under the leadership of a candidate who, the President believed, had sold out to the worst elements in his party.

Roosevelt hungered to get on the stump—yet he had to proceed cautiously. At all costs he wanted to preserve his symbolic role of commander in chief. He had said that he would not travel more than twelve hours from Washington, in case he was needed there in an emergency; and despite frantic pleas for personal appearances elsewhere, he stuck to this plan. A Secret Service ban on the presidential use of airplanes meant that the President could campaign only in parts of the Northeast. Roosevelt managed to make some automobile tours that were both defense inspections and campaign trips, but he knew that his greatest weapon was the radio, through which he could reach the whole country. Exploitation of the radio seemed all the more urgent because of Republican supremacy in the press, and it seemed all the more agreeable because Willkie was at his most graceless and ineffective at the microphone.

Roosevelt opened his campaign in Philadelphia on the night of October 23. He declared that he welcomed the chance to answer falsifications with facts. “I am an old campaigner,” he proclaimed, “and I love a good fight.” The huge crowd roared.

Never had the old campaigner been in better form, reporters agreed. He was in turn intimate, ironic, bitter, sly, sarcastic, indignant, solemn. He lifted his eyes in mock horror, rolled his head sidewise, shook with laughter. “He’s all the Barrymores rolled in one,” a reporter exclaimed.

Slowly and deliberately Roosevelt answered Willkie’s charge of secret understandings.

“I give to you and to the people of this country this most solemn assurance: There is no secret treaty, no secret obligation, no secret commitment, no secret understanding in any shape or form, direct or indirect, with any other Government, or any other nation in any part of the world, to involve this nation in any war or for any other purpose.”

The President struck out at a Republican charge, as he described it, that his administration had not made one man a job.

“I say that those statements are false. I say that the figures of employment, of production, of earnings, of general business activity—all prove that they are false.

“The tears, the crocodile tears, for the laboring man and laboring woman now being shed in this campaign come from those same Republican leaders who had their chance to prove their love for labor in 1932—and missed it.

“Back in 1932, those leaders were willing to let the workers starve if they could not get a job.

“Back in 1932, they were not willing to guarantee collective bargaining.

“Back in 1932, they met the demands of unemployed veterans with troops and tanks.

“Back in 1932, they raised their hands in horror at the thought of fixing a minimum wage or maximum hours for labor; they never gave one thought to such things as pensions for old age or insurance for the unemployed.

“In 1940, eight years later, what a different tune is played by them! It is a tune played against a sounding board of election day. It is a tune with overtones which whisper: ‘Votes, votes, votes.’ ”

On the subject of economic recovery Roosevelt quoted the financial section of the New York Times against the editorial page. “Wouldn’t it be nice,” he taunted, “if the editorial writers of The New York Times could get acquainted with their own business experts?”

Five nights later, after driving during the day for fourteen hours through New York City streets before probably two million people, Roosevelt charged in Madison Square Garden that the Republican leaders were “playing politics with national defense.” Such a charge was opportune; Italy had just invaded Greece, and several times during the day the President interrupted his street tour to telephone the State Department. He made no “stab-in-the-back” remark in the Garden—only an expression of sorrow for both the Italian and Greek peoples. Most of his speech was a slashing attack on the Republican leaders—Hoover, Taft, McNary, Vandenberg—for opposing defense measures in the past and now condemning the administration for starving the armed forces.

“Yes, it is a remarkable somersault,” Roosevelt said, his voice dripping with sarcasm. “I wonder if the election could have something to do with it.”

While drafting this speech Rosenman and Sherwood had hit on the rhythmic sequence of “Martin, Barton, and Fish.” They handed Roosevelt a draft with this phrase to see if he would catch the rhythm. He did: his eyes twinkled as he repeated it several times, swinging his finger in cadence to show how he would put it across. The crowd in Madison Square Garden guffawed and were soon repeating the phrase with him.

Willkie was staggered by this assault on him through his weakest allies. As the campaign rose to a new peak of bitterness and intensity, he desperately doubled his bets. On October 30, the day after Roosevelt officiated at the drawing of selective service numbers, Willkie shouted that on the basis of Roosevelt’s record of broken promises, his election would mean war within six months.

Roosevelt was en route to Boston the day that Willkie made this charge. By now Democratic leaders were more jittery than ever; the Gallup poll showed Willkie almost abreast of Roosevelt nationally and ahead of him in New York and other key states. Each time his train stopped for rear-platform speeches on the way to Boston messages came in from Flynn and others pleading with Roosevelt to answer Willkie’s charges. The President, in fact, had already compromised on the essential issue throughout the whole campaign by stressing his love for peace and neutrality and his record on defense rather than expounding his crucial policy of aiding Britain even at the risk of war. But, as Roosevelt sat in a low-backed armchair in his private car, Hopkins handed him a telegram from Flynn insisting that he must reassure the people again about not sending Americans into foreign wars.

“But how often do they expect me to say that?” Roosevelt asked. “It’s in the Democratic platform and I’ve repeated it a hundred times.”

“Evidently,” said Sherwood, “you’ve got to say it again—and again —and again.”

The President liked the phrase. Then the speech writers ran into a snag on the sentence “Your boys are not going to be sent into foreign wars.” Roosevelt in past talks had always added the words “except in case of attack”; he had, indeed, insisted on this qualification during the Chicago convention even when he was willing otherwise to compromise on the foreign policy plank. Now he wanted to drop the proviso. Rosenman asked why.

Roosevelt’s face was drawn and gray. He had to bend before the fury of Willkie’s attack—but he would not admit it.

“It’s not necessary,” he said shortly. “If we’re attacked it’s no longer a foreign war.”

That night in Boston, after a tumultuous reception, Roosevelt catalogued the anti-New Deal voting record of “Martin, Barton and Fish” and compared it with the “soothing syrup” the Republicans spread on thick. Appealing by radio to the farming West, he wondered out loud if Martin—whom Willkie had once described as representing “all that is finest in American public life”—was slated for Secretary of Agriculture. And to the “mothers and fathers of America,” he made the assurance that in years to come would be repeated mockingly by thousands of isolationist orators:

“I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again and again:

“Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.”

By now Roosevelt was facing a threat from a new quarter, and he used his next campaign speech two nights later in Brooklyn to counter it. The Republicans had scored a singular coup a few nights before when John L. Lewis not only came out for Willkie but announced that he would resign as president of the CIO if Roosevelt won. The President’s sole motive and goal, said the black-maned old miners’ chief in his Shakespearean voice, was war. By asserting that a victory for Roosevelt would be in effect a vote of no confidence in himself, Lewis was able at last to come to grips with the slippery rival he hated—but he was doing so on the President’s own ground. With the Communists also attacking the administration hysterically, Roosevelt saw his opening and struck hard.

“There is something very ominous,” Roosevelt said in Brooklyn, “in this combination that has been forming within the Republican party between the extreme reactionary and the extreme radical elements of this country.

“There is no common ground upon which they can unite—we know that—unless it be their common will to power, and their impatience with the normal democratic processes to produce overnight the inconsistent dictatorial ends that they, each of them, seek.” Toward the end of his speech Roosevelt quoted a Philadelphia Republican leader as having said, “The President’s only supporters are paupers, those who earn less than $1200 and aren’t worth that, and the Roosevelt family.”

“ ‘Paupers’ who are not worth their salt,” Roosevelt exclaimed,“—there speaks the true sentiment of the Republican leadership in this year of grace.

“Can the Republican leaders deny that this all too prevailing Republican sentiment is a direct, vicious, unpatriotic appeal to class hatred and class contempt?

“That, my friends, is just what I am fighting against with all my heart and soul.…”

While the White House moved fast to turn Lewis’ district leaders against the mine leader, Roosevelt ended the campaign in Cleveland on the lofty note he loved. The Cleveland speech was perhaps the hardest he had ever had to write. Rosenman and Sherwood had not had a chance to start preparing anything until the day before, and they were exhausted. All night the two labored on the campaign train, catching cat naps on beds littered with toast crusts and gobs of cottage cheese. By midday the next day, when the draft was ready, Sherwood was shocked at Roosevelt’s appearance—the dark circles under his eyes, the gray face, the sagging jowls. The President during the morning had been making rear-platform appearances, greeting people, pumping hands; he had felt compelled to say at Buffalo, “Your President says this country is not going to war.” Roosevelt was dreadfully tired.

But during lunch, as the President told long, dull stories about Maine lobstermen that all present had heard many times, Sherwood saw his enormous powers of recuperation at work. Soon Roosevelt was demanding jocularly, “What have you three cutthroats been doing to my speech?” For six hours straight, except when he had to put on his leg braces and walk out to the rear platform on Pa Watson’s arm, Roosevelt worked on his speech. Out of the noise and dirt of the car, out of the rhythm of the train as it chugged slowly through the falling rain, out of the chatter and scuffle of visiting politicos, out of the utter weariness of Roosevelt and his advisers, came somehow a superb campaign speech. That night forty thousand men and women cheered their hearts out as Roosevelt stood before them in a vast auditorium. He began quietly but before the end he was striking a personal and passionate note.

“During these years while our democracy advanced on many fields of battle, I have had the great privilege of being your President. No personal ambition of any man could desire more than that.

“It is a hard task. It is a task from which there is no escape day or night.

“And through it all there have been two thoughts uppermost in my mind—to preserve peace in our land; and to make the forces of democracy work for the benefit of the common people of America.

“Seven years ago I started with loyal helpers and with the trust and faith and support of millions of ordinary Americans.

“The way was difficult—the path was dark, but we have moved steadily forward to the open fields and the glowing light that shines ahead.

“The way of our lives seems clearer now, if we but follow the charts and the guides of our democratic faith.

“There is—there is a great storm raging now, a storm that makes things harder for the world. And that storm, which did not start in this land of ours, is the true reason that I would like to stick by those people of ours—yes, stick by until we reach the clear, sure footing ahead.

“And we will make it—we will make it before the next term is over.

“We will make it; and the world, we hope, will make it, too.

“When that term is over there will be another President, and many more Presidents in the years to come, and I think that, in the years to come, that word ‘President’ will be a word to cheer the hearts of common men and women everywhere.

“Our future belongs to us Americans.

“It is for us to design it; for us to build it.…”

The campaign spluttered to a surly finish. Willkie, his voice still a hoarse whisper, charged once more that a third term would mean dictatorship and war. On election eve Roosevelt gave his usual “nonpartisan” talk. After urging that all vote the next day and then help restore unity, he ended with an old prayer that he remembered from Groton forty years before:

“… Bless our land with honorable industry, sound learning, and pure manners. Save us from violence, discord, and confusion; from pride and arrogancy, and from every evil way. Defend our liberties, and fashion into one united people the multitudes brought hither out of many kindreds and tongues.…”

Next day fifty million Americans—millions more than ever before—streamed to the polls. Roosevelt himself was the picture of genial self-confidence when he faced reporters at the Hyde Park polling place. Patiently he posed while the photographers shot him from every angle. “Will you wave at the trees, Mr. President?” he was asked. “Go climb a tree!” Roosevelt said. “You know I never wave at trees unless they have leaves on them.” But then, quickly relenting, he waved at the trees while cameras clicked.

That night the house stood dark and quiet on its height above the Hudson. On a staff above the portico the presidential flag, with its shield, eagle, and white stars, flapped quietly in the mild November air. Inside the mood was tensely gay. Much of the family was there, along with a host of friends. Little groups clustered around radios throughout the house. Roosevelt sat at the family dining-room table. In front of him were big tally sheets and a row of freshly sharpened pencils. News tickers chattered nearby.

At first the President was calm and businesslike. The early returns were mixed. Morgenthau, nervous and fussy, bustled in and out of the room. Suddenly Mike Reilly, the President’s bodyguard, noticed that Roosevelt had broken into a heavy sweat. Something in the returns had upset him. It was the first time Reilly had ever seen him lose his nerve.

“Mike,” Roosevelt said suddenly, “I don’t want to see anybody in here.”

“Including your family, Mr. President?”

“I said ‘anybody,’ ” Roosevelt answered in a grim tone.

Reilly left the room to tell Mrs. Roosevelt and to intercept Morgenthau’s next trip back to the dining room. Inside, Roosevelt sat before his charts. His coat was off; his tie hung low; his soft shirt clung around the big shoulders. The news tickers clattered feverishly.…

Was this the end of it all? Better by far not to have run for office again than to go down to defeat now. All his personal enemies gathered in one camp—big businessmen like Willkie, Democratic bolters like Al Smith and the rest of them, newspaper publishers like Hearst and Howard, the turncoats like John Lewis, the obstructionists on Capitol Hill, the isolationists, the Communists—would this strange coalition at last knock him down and write his epitaph in history as a power-grasping dictator rebuked by a free people?

In Hoboken and in St. Louis, in Middletown and in a South Carolina crossroads school, ballots were counted and figures phoned to the court house; numbers were tumbled onto telegraph wires, grouped with other figures, flashed to the state capitals, combined with more figures; and now the little machines were spewing them out. In the black numbers was being struck some cosmic balance—the courageous acts, the forthright utterances, the hard decisions, the great achievements, stretching from the Hundred Days to the destroyer deal, from social security to selective service. Struck in this balance, too, were the compromises and the evasions, the deals and the manipulations, the hopes unrealized, the promises unfulfilled.

The smoke curled up from the cigarette in the long holder. The Hyde Park returns were not in yet. But they would probably go against him. It was strange, in a way. He had never really left Hyde Park. He had always left part of himself in this world of tranquil estates, hard-working farmers, St. James’s church, the trees and the fields and the river. He had never wholly left the world of his mother, now sitting with friends in another room. Yet this was the world he had never won over politically.

In the little black numbers marching out of the ticker, not only Roosevelt but the whole New Deal was on trial. The relentless figures were a summation of so much—of the clarion call of 1933, the sultry summer of 1935, the long trips through the country, the court fight, the purge, the pleas to the dictators, the arming of the nation. A generation of American ideas was on trial too. Eighty precincts from New Jersey reporting—what verdict would come from Newark slums and the Jersey flats on a credo that had repudiated McKinley, moved beyond Wilson, and somehow fused a dozen differing doctrines and traditions?

From all over America the atoms of judgment streamed through the ticker and took their place on the tally sheets. Still Willkie ran strong. Disappointing first returns were coming in from New York—New York, the very image of the America from which the New Deal coalition had been built. New York—the heart of his political empire, the state of Uncle Ted, of law firms like the one he had worked for on Wall Street, of Tammany bosses. New York—the state that had rebuked him in 1914, and again in 1920, then favored him by the tiny margin of 1928 and the huge avalanche of 1930.

The ash dropped from the cigarette; Mike Reilly stood stolidly outside the door. Was this the end of Jim Farley’s journey to the Elks’ convention; the final landing for the plane that had carried Roosevelt from Albany to the Chicago convention of 1932? Would the whole great adventure follow the Blue Eagle into defeat? New York City returns were coming in—even the city was undependable in this strange election. Here were the urban masses—the Italians, Jews, Negroes, Germans, Irish—who had benefited from the New Deal and who had sustained it. But now the New Deal was no longer new, and other, sharper issues had emerged as Hitler changed the face of politics everywhere. One report had reached Roosevelt that in New York City only the Jews were solid for him.

And so the returns poured in, filling in the little pieces that would, before the night was over, make up a vast mosaic—and an answer. The voters, in the last analysis, were not passing on a unity, on a completed sum of the New Deal. For when all its parts were added and subtracted, what remained was less a quantity than a spirit. Seven years were on trial, seven eventful years crammed with deeds; yet it was not the deeds that remained—though their monuments would long endure—so much as a distillation of the pageant of the 1930’s, embodied in the spirit that was the New Deal—boldness, eclecticism, experimentation, a devotion to building the grade crossing and housing the homeless that transcended ideology and spoke the idiom of American tradition. There was in all this not so much a philosophy as a common sense. And it was the common sense of the American people that must speak tonight.…

Then there was a stir throughout the house. Slowly but with gathering force, the numbers on the charts started to shift their direction. Reports began to arrive of a great surge of Roosevelt strength, a surge that would go on until midnight. New York, Massachusetts, Illinois, Pennsylvania—the great urban states were falling in line behind the President. By now Roosevelt was smiling again, the door was opened, and in came family and friends with more reports of victory. Then came the usual torchlight parade from Hyde Park center, lighted by photographers’ flash bulbs, and the usual homey talk by the President: “I will still be the same Franklin Roosevelt you have always known.…”

In the ballroom of the Hotel Commodore in New York thousands of Willkie supporters had gathered in a celebrating mood. For a time all were jubilant; then, as the sad reports poured in, the crowd slowly dwindled until only a dejected band of Willkieites remained. The candidate appeared for a short talk late in the evening. “Don’t be afraid and never quit,” he cried hoarsely. Not till the next day did he send Roosevelt a congratulatory wire.

The final results spelled a decisive victory for Roosevelt. The popular vote was 27,243,466 to 22,304,755; the electoral vote was 449 to 82. Besides Maine, Vermont, and six farm states, Willkie carried only Indiana and Michigan. Roosevelt won every city in the country with over 400,000 population except Cincinnati. On the other hand, Willkie had gained five million more votes than Landon had in 1936; Roosevelt’s plurality was the smallest of any winning candidate since 1916. The President’s margin in New York—about 225,000—was his lowest since his hairbreadth victory for governor in 1928.

But, while Roosevelt lost some support in almost every major group, he dropped off only slightly in the huge lower and lower-middle income groups. His continued substantial support among the “masses” was the key to his victory. Labor, including coal miners, stayed with the President. Lewis’s efforts had fallen flat, and he duly surrendered the CIO presidency as a symbol of his total defeat by Roosevelt in the political arena. There were indications that class voting in 1940 was more solid than four years before. “I’ll say it even though it doesn’t sound nice,” a Detroit auto unionist told reporter Samuel Lubell shortly after the election. “We’ve grown class conscious.”

If Willkie’s appeals to the workers on economic issues had proved unavailing, his raising of the war issue did cut into Roosevelt’s vote. Pro-German and Italian and anti-British elements swung sharply against the President, and these were only partly offset by the Jews, eastern seaboard Yankee internationalists, and national groups such as Poles and Norwegians who could not forget Hitler’s occupation of the “old country.” Roosevelt actually increased his vote in northern New England over 1936, though by a small margin.

Unquestionably Roosevelt had been lucky in at least two respects: the crisis in Europe and the first flush of returning prosperity. The former took the force out of Willkie’s main foreign policy appeal; the latter took the sting out of his main domestic argument, namely the Depression. Poll after poll showed that the sharper the crisis, the more the voters clung to Roosevelt. The emergency situation seemed also wholly to counteract Willkie’s third-term warnings.

Luck—but marvelous skill as well. The President’s political timing had never been better, his speeches for the most part had never been more skillful, his thrusts at enemy weak points never more telling. More than this, he had exploited his one great line of communication to the people—the radio—while countering Willkie effectively in the very medium—the newspapers—that the latter could claim as peculiarly his own. Willkie was ineffective over the radio; and, while Willkie got more favorable mention in the press, Roosevelt got more attention in the press. The old political adage held: bad publicity is better than no publicity.

In the last analysis Roosevelt himself was the issue. His campaign poses with the guns and ships had paid off; but his captaincy of a generation paid off too. His victory was largely a personal one; the Democrats gained only six seats in the House in 1940 after the slump of 1938, and lost three in the Senate. The future had been made possible for Roosevelt, but what was foretold for his party, his program, his country, and his world, no man could tell.