NEARLY EVERY MEMORY I have of my childhood is connected with my mother. She was such a philosophical lady. One does not need a university degree to be philosophical. The ancient Greeks tell us that the word philosophy can be broken up into philo, which means love of and Sophia, which means wisdom. So someone who spouts wise sayings can be philosophical, but wisdom need not always be intellectual and acquired. It can be intuitive. Mak was a wise woman indeed. She was uneducated like most women of her time in that she was not literate. But she was certainly educated by the University of Life. My strongest memory of her is her genteel manner and the amazing wisdom that spouted from her lips. I may not recall all her sayings in the exact way she said them but I certainly believe I have captured the essence of what she said.

“It’s not where you live that counts but how you live,” she used to say.

This would be great if you were living in comfort and luxury but when you were like me, a child in Kampong Potong Pasir, where you had to live among rats scuttling along the cement floor or centipedes falling off the attap roof, you would have wondered if my mother’s philosophy was for real. But she was for real. I can say with my hand on my heart that she was the most influential person in my life. It was her positive philosophy and attitude that nurtured me and set me up for as long as I may live.

I was born in March 1951. The year of my birth was auspicious for the island of Singapore and its people. In September that year, it was proclaimed a City by the British. In later years, I heard stories of how the Padang had so many people celebrating the momentous occasion that the field of grass which gave it its name was blocked from view. Laughter and cries of joy burst out when the fireworks erupted in a myriad of colours above the Esplanade, which was then a tree-lined walkway by the sea. To crown the event, an illuminated dragon-float glided across the seafront to the delight of everyone present. So my birth was also the birth of a hope for independence for our nation.

By the time I was three, people were crying out, “We want Self-rule! We want Self-rule!”

Just as I was about to turn four, the country was caught in election fever.

“We want our own local leader!” People cried out to the British rulers.

Our village was a hive of excitement. Our kampong road had never seen such a parade of vehicles, vans and open-topped lorries, trundling down its pot-holed lanes, their wheels raising clouds of dust. The party leaders shouted political slogans and promises from hand-held megaphones. There was David Marshall, from the Labour Front Party, Lee Kuan Yew from the newly formed People’s Action Party, and even an independent candidate, Ahmad Ibrahim. Great crowds of people rallied around them, inspiring everyone with their messages.

“We want to improve your lives,” they said. “We will provide you with running water and electricity, and food to quiet your rumbling stomachs.”

Villages like ours were served by wells, and we had no running water in the houses. Usually the stand-pipe, which provided drinking water, was some distance away. The electricity in the city did not reach our homes. Our homes were lit by hurricane lamps, kerosene or carbide lamps and candles. And the majority of villagers were poor and uneducated. The political candidates played on our lack of education, obliquely persuading us that the colonial government did not have our interests at heart but that local government would. We were motivated to act from hunger and to be free from the squalor of our everyday living. So villagers turned out en masse on polling day, April 2, to vote. David Marshall won a narrow victory and became our country’s first chief minister. Sadly his Labour Front Government was jinxed; a strike took place soon after he took office, and there were many more after that.

That particular strike was by the Hock Lee Amalgamated Bus Company. Two anti-colonists, Fong Swee Suan and Lim Chin Siong, who were the leaders of The Singapore Bus Workers Union, were reported to incite their members, saying “You are deluded if you think that the Labour Party is not being controlled by the Colonial Government. Don’t be deceived. This government is only a pawn for the British! What have they done for you, eh? What? You work day and night and you still get so little pay and have not enough to eat. You live in villages that have no running water or electricity, where sanitation is appalling and disease rampant. We want better terms and conditions!”

Indeed, bus drivers and conductors, Ah Chye, Peng An, Salleh and Gurjit were from rural villages like ours. They had experienced the devastating flood that had hit Potong Pasir the previous year, in 1954. Houses in the kampong were made with wooden walls and palm-thatched attap roofs. So they were flimsy and could not withstand the heavy monsoon and surging flood waters. Many people became homeless or lost possessions. Therefore in villages like ours, people were looking for a saviour to remove our deprivations and give us a better life. Lowly paid folks like Ah Chye, Peng An, Salleh and Gurjit decided to join the strikers in the hope that they could provide more for their families.

“Our pay is too low!” The strikers shouted, together with all the others, raising a thicket of fists into the air. “We can’t feed our wives and children or buy shoes for them. We work very long hours in terrible conditions yet our stomachs still rumble!”

On May 12, an event which came to be known as Black Thursday devastated the country. Nearly 2,000 students from Chinese Middle Schools joined the strikers of the Hock Lee Bus Company. Students from Chinese schools were disgruntled with the colonial government because their education was not recognised. Also they were not permitted to get into the University of Malaya even when they had the right qualifications.

The strikers caused a major riot in Alexandra Road and Tiong Bahru. They barricaded the depots and stopped the buses from leaving the depots. Wives and mothers like Ah Sum, Ah Moey, Khatija and Gita from our village took out their tingkat or tiffin carriers. These were two- or three-tiered food containers, the enamel ones painted with brightly coloured flowers and birds. The steel ones were plain or carved. Mothers and wives filled these with delicious food to take to their husbands and sons behind the picket line. They had to walk miles, as the city’s transport system had ground to a halt. Only those with private cars or who could afford taxis and pawang chiar could still travel comfortably.

“Aiiyah! Eat something-lah!” Ah Sum persuaded her husband.

Students from the Chinese schools brought food and even entertained the workers by singing and dancing. Had it remained a peaceful strike, no one would have been hurt. The police tried to break them up with water cannons and tear gas, so both strikers and students retaliated, with devastating results. Ah Moey came back to the village distraught and in tears.

“What happened? What happened?” Neighbours asked her.

“Sway, sway-lah! Misfortune, misfortune-lah. My husband, Peng An. His head was smashed by a police truncheon. He’s in hospital now.”

It was indeed a day of darkness.

Across the Kallang River from our village was an English Missionary School, Saint Andrew’s School, which was run by a man called Canon Reginald Keith Sorby Adams. He had been nicknamed The Fighting Padre as it was he who introduced boxing as a sport to the school. He was one of the few Europeans or white men seen around our village, handing out alms or just being friendly. Besides this English missionary school was a Chinese school in Kampong Potong Pasir. Unlike St. Andrew’s, which was built of concrete, the Chinese school was an open wooden hut with wooden flooring, its roof thatched with attap. The pupils sat on long wooden benches facing an old-fashioned blackboard which the teacher would scratch with his white chalk. The colonial government did not fund Chinese education, so that opened the sluice gates of opportunity for the communists to spread their influence. China sent teachers, school-books and funds, purportedly to educate their Chinese nationals abroad. Most of the pupils in our village school were from Lai Par, the inner sanctum of Kampong Potong Pasir where their parents tilled the earth and grew vegetables.

“Yi, Er, San, Si ... One, Two, Three, Four...”

Mandarin was not spoken in our part of the village except at that school. Chinese people in our village mostly spoke Teochew or Hokkien and some Cantonese. The other village children, including myself, would crowd round the school listening to this foreign language. Apparently it was this language that linked the local Chinese to their Motherland and it was this sentiment that the communist insurgents played upon. People liked to belong somewhere and at this point in time, Singapore still felt like a staging post, not yet its own nation. The different immigrant races still thought of their former countries as their Motherlands. However, Peranakans, because of their mixed heritage, have an affiliation to China but consider Malaya as their home. At this point in history, the word, Malaya was used interchangeably to include Singapore, and did not merely refer to the Federated States of Malaya. That was why the first university in our country was called the University of Malaya.

It was through schools like those in our village that the communists spelled out their mission to overthrow the Colonial government. In our innocence, the village children and I spied on the school. The lessons were carried out in a sing-song manner with lots of rote learning, where the pupils repeated again and again what the teacher taught. If the teacher was male, he’d wear a short-sleeved white shirt with navy-blue trousers. If the teacher was female, she’d wear a cheongsam, and her face was severely framed with a straight page-boy haircut.

“Why fight for them?” the communists had mooted to impressionable teenagers who were on the cusp of being drafted into National Service the previous year. “Where were they in our country’s time of need? They deserted us and let the Japanese walk in. Isn’t it time that we threw the British out?”

But of course, I was too little to know anything of the social unrest or political stirrings. All I knew was, I was not comfortable with the strange-sounding Mandarin language. I was comfortable with Malay and our Baba patois, which was Malay mixed or champur with Hokkien and Teochew. Like all children, my only concern was for my own welfare in my own little world.

Despite the fact that my family had difficulty getting our quota of food and vitamins for each day, I had a luxuriant head of hair like my mother. But unlike my mother’s, mine was so straight it sprung out from my head like a stiff broomstick, the kind of broomstick which we used to make from the spine of coconut leaves, called sapu lidi. We collected bunches of coconut leaves, then shaved the green parts of the leaf until only the spine remained. The spines were dried in the sun until they browned, when we tied them together with jute strings to make a broom. It was perfect for sweeping up sandy yards, like those at the back of our attap house where banana, papaya and angsana trees grew. But when my hair grew long, it softened and when plaited, it was manageable. There was so much of it, hanging like a black curtain down my back and I became so proud of it. But Pride goeth before a fall. I am sure you have heard the saying. It was my first big lesson in life.

One of my most pleasurable memories is of my mother combing my long hair. When the sun beat down mercilessly, our zinc roofed kitchen became a sweltering oven, so we would cool ourselves by sitting on the threshold of our house trying to catch the breeze that passed. I usually sat in the cradle of her knees and she would run a multi-toothed comb again and again through my hair till it shone. The lorongs or passages between the rows of houses were so narrow that if you stretched your legs out, you could touch the legs of the neighbours sitting opposite on their threshold.

“Ei Nonya,” Mak Ahyee, our neighbour asked. She like everyone in the village, addressed my mother with the Peranakan term for a lady, nonya. “What oil do you use for her hair?”

“Coconut milk. Freshly squeezed from grated coconut,” Mak said. “I put it on her head and allow it to soak through into the hair for an hour to condition it.”

“So beautiful. So beautiful!”

Mak deftly plaited my hair into two thick plaits. And then I went off to play with the rest of the kampong children. We were an assortment of Malay, Indian, Punjabi, Eurasian and Chinese young people of various ages. Many of the children were not educated, so our common language was Malay.

“Hari ini kita main chapteh. Today we’ll play chapteh,” Abu said. He was the elder bother of my friend, Fatima. He was only twelve but always styled himself the leader. If my big brothers were at home, they took the part. But Abu had a certain je ne sais quoi that made him a natural leader.

Some people could afford store-bought chaptehs with a thick rubber base and plumes of colourful feathers. But we hardly ever bought toys from stores. If we were lucky, the English families living at the top of the hill at Atas Bukit (literally meaning on-top-of-hill) would throw out their children’s unwanted toys. Sometimes they were broken, other times, just a little bit damaged and if we were extremely lucky, only because they were old. Their rubbish bins became our treasure troves. Sometimes we even salvaged uneaten food from them: a half-eaten banana or apple, left-over cake, boiled sweets which had melted into their wrappers. But English children did not play chapteh. So we had to learn to make our own. With a flourish, Abu produced one that he had made.

“Wah!!!” All the children exclaimed at its magnificence.

He had cut rubber circles from disused car-tyres and nailed them together. On the spikes of the nails, he had impaled several feathers. The feathers looked fresh, as if they had just been plucked recently from a chicken or duck, and perhaps one from a mynah bird. Abu was not opposed to pursuing a chicken to pluck its feathers. I could imagine him chasing the distraught chicken as it clucked and raced around in mindless circles out of sheer panic. Round the base of the quills, he had strapped jute string to hold everything together.

“The rule is,” he pronounced authoritatively. “You can only kick it with the sole of your foot. Otherwise you are out! The person who keeps it in the air longest with the most number of kicks wins.”

“Can I use my left foot?” One of the other boys asked.

Village children hardly ever wore any footwear. If we had to visit the filthy outhouses, we would put on our wooden clogs, called char kiak in Hokkien, terompah in Malay. They were the must-have items in kampongs. The stocky char kiaks were usually made with an inch or more thickness, so you felt taller when you were wearing them. It was the platform footwear of the fifties. They were very functional, as they served the purpose of keeping feet dry and clean when traversing puddles and fly-riddled cow-pats, which were numerous in the villages. There was a char kiak shop in our village where the craftsmen shaved wooden blocks by hand to fashion them into clogs. If you passed the shop, you could smell the aromatic smell of fresh wood and see wood shavings on the dirt floor, plus stacks of unvarnished clogs waiting to be painted. Char kiaks came in bright colours like red and yellow, with matching coloured plastic straps. When you walked in them on a cement or concrete street or floor, the clogs made a characteristic sound, clok, clok clok; hence its English onomatopoeic name. You could never creep up on someone undetected! When rubber flip-flops came into fashion, people opted for them because they were less cumbersome and less noisy.

“Left foot. Right foot. I don’t care. As long as it’s your tapak kaki. The sole of your foot.” Abu emphasised.

I was one of the few girls who joined in games with the boys. I was a boy at heart, even at that young age, wanting to do adventurous things, wanting not to be restricted to activities merely of my gender. Because I was so little, they humoured me and allowed me to play. But I kicked up sand and dust and even more dust while they laughed at my futile attempts.

But I enjoyed playing with the girls too. Although Fatima and I got on well, my best friend was really Parvathi, an Indian girl three years older than myself. We loved masak-masak – the word literally meant cooking but it was a game of make-believe, pretending that we were grown-up women making a home, cooking, having babies. But sadly, Parvathi never made it to womanhood, nor had a real baby. I have told her story, which contains a vital lesson, in the chapter “Dying to be Free.”

Our pretend-babies were fashioned out of old rags or straw. Some of our babies were handicapped, lacking an eye or a limb; they were the dolls we rescued from the bins at Atas Bukit. But we took care of them; we bathed, dressed and fed them. We were training to be real mothers, never rejecting our children no matter what condition they were in. Engrossed in making cakes from mud and drinks from drain-water, our clothes became dirty, our hair and faces matted with dirt. Sometimes in digging around in the sand, we encountered squiggly earth-worms and we squealed in fright. The boys were amused but usually took these from us to use them as bait to catch fish or belot, eels, in the river or mud-banks. The main river that ran through Kampong Potong Pasir – the Kallang River. – used to be much broader than it is today, with water swelling during the monsoon periods, flooding its banks. Eels made their homes in its moist banks. Since many kampong folk could not afford to buy food, they had to find it in the countryside: eels, fish from the river, birds’ eggs, ubi kayu or tapioca and coconut that grew in the wilderness.

A good Peranakan cook like my mother could make delicious meals out of most things. Peranakan girls were taught to cook at an early age. Mak’s best eel dish was cooked in rempah, a rich but dry curry paste. She would cut the eel into slices, marinate them with turmeric and chilli powder, then fry each piece. This took away the sliminess that was often associated with fresh eels. Then she pounded fresh chillies, onions, garlic, ginger, coriander and cumin seeds in her batu lesong or rolled them on her granite batu gilling to make them into a thick paste. She would sauté the curry paste in the kwali over the coal fire till the fragrance filled the air and made our mouths water. She’d squeeze milk out of a coconut but used only the first press called pati-santan and added this to the thick curry. Then she’d slip the cooked eels into this sauce and allow the sauce to thicken and coat the eel slices. Eaten with boiled rice, this was absolutely delicious and was a feast for us!

Of course, playing in the sand, we picked up germs. And other things too. But we were never very concerned about things like that. Well, I was not concerned. Not until my scalp started to itch. I scratched and scratched and scratched.

“Stop scratching your head. All your hair will fall out!” Mak admonished.

But I did not stop. The itching became so intense, I started to cry.

“Come here!” She said. “Let me look.”

She let out a yelp.

“Kutu! Kutu!” She shouted in horror. “Lice! Lice! My God, you’re infested!”

So she waged war on them. She parted each section of my hair, ferreted out the little mites and squeezed them between her thumb and finger. Each louse departed its mortal life with an explosion of pungent odour. The smell made me want to throw up so I howled some more. Serve me right for being so proud of my beautiful hair!

We could not afford posh things like Palmolive soap and shampoos then, though we dreamed of their creamy softness when we looked at advertisements in posters and women’s magazines like Her World. But they were beyond our reach. We had to wash our hair and our body with the same Sunlight cake soap that Mak used for washing the clothes. For more stubborn stains, she used a black cake of carbolic soap that smelled foul. She dragged me to our communal bathroom, a rectangular wooden wall with a concrete floor that surrounded a well, the top open to the sky. It never made sense to me to bathe on rainy days when it would do just as well to stand in the rain outside.

“Sit!” She ordered.

Mak drew up several buckets of water, careful not to draw up the two catfish that were put down the well to eat up mosquitoes. Fortunately, due to the recent rain, the water was clear. During the dry months, one would draw up thick muddy water. It was not a joy to bathe during that period. Then we would make the trek to a local spring the kampong folks called Pipe Besar. Mak tipped the water into a baldi, a steel oval-shaped bucket with a ridge underfoot. After wetting my hair, she scrubbed and scrubbed my head with the carbolic soap. It hurt.

“Ow! Ow! Ow!” I went.

“Keep still! Would you rather keep all these lice in your hair?”

But even after all her strenuous efforts, the lice still proliferated.

“Okay no choice now,” Mak said. “It’s the kerosene treatment for you.”

“Oh, no Mak, please, no!”

I had seen Mak Ah Yee treat her daughter Ah Yee with the kerosene treatment, and it was awful. The whole scalp was doused with kerosene. It was obviously a folk remedy that must have produced the desired results.

My mother was a determined lady.

Kerosene came in a rectangular metal container and it was used to fuel kerosene stoves, although Mak still preferred to cook on her clay stove with coals. When Mak poured some into an enamel mug, its fumes rose to my nostrils. I nearly retched. My mother forced me to sit still and placed a towel around my shoulders. You know what it is like when someone forces something on you, telling you that it is for your own good though you hate every minute of it. That was what it was like, me sitting with my head bowed as she rinsed my whole head of hair with the stuff. It felt yucky and it stank. Where I had scratched my scalp previously, the kerosene made the scalp sting.

“Sit there for an hour or so,” she said. “The kerosene should murder the lice!”

I was utterly miserable.

Even at that tender age, I had a wild imagination. What if someone threw a lighted match in my direction? My head could be set alight like Moses’ burning bush! No divine revelation there, or the voice of God, just me screaming in sheer agony. That would make my mother feel sorry for me. It would certainly roast the little buggers in my hair!

But my misery was nothing compared to that of families caught in the strikes and riots. Altogether there were 275 strikes in 1955. Every now and again, adults would shout out warnings and the children were ushered indoors in haste. Our wooden windows would be shuttered and doors urgently bolted. We cowered behind our wooden walls and listened to the stampede of rushing feet running past our doors. Trouble-makers and rioters often sought refuge in kampongs because of the maze of lorongs that tended to confuse the uninitiated, like the English policemen. In 1950, when the Maria Hertogh affair caused the Muslims to retaliate against the colonial government, many of the rioters sought refuge in the kampongs. More often than not, the colonial police were reluctant to enter local villages because the rioters or trouble-makers often had their supporters lying in wait in the kampongs. The sympathisers would stand in menacing groups, wielding agrarian weapons of destruction like parangs (machete-looking knives) and cangkuls (hoes). Kampong Tai Seng, near Paya Lebar, was notorious for harbouring rioters, hardened criminals and gangsters.

My own black day came when my mother decided to cut off my long hair. I was too young to appreciate the blackness of what had just taken place in the country, though I was not too young to imbibe the sense of tension that arose from it. The Straits Times reported it for weeks. Adults in our village talked about it for days on end, clustering in the narrow lorongs or under the spread of angsana trees. We followed bus-driver Peng An’s progress in hospital and rejoiced with Ah Moey when her husband finally came home, even though on crutches, his head bandaged. Ah Moey had thought he would not live. But my childish focus did not extend further than myself.

Mak came toward me like a malevolent creature with her scissors.

“It’s for your own good,” she said, as I tried to escape her. “Less hair means less kutu!”

As she snipped, my long hair spiralled downwards to our cement floor. I wept. When I looked in the mirror afterwards and saw my mutilated hair, I howled.

“You’re so wicked! Wicked! Wicked! Wicked!”

It is the only recollection I have of saying something nasty to my mother.

Normally if we said anything rude or nasty, we would get the sumbat sambal belachan treatment. It was a torture worse than hell for us kids. The intense heat and sting of the chilli-padi, the hottest chilli in South East Asia, would make you leap up and down like a crazed monkey. That’s why Peranakans have a saying, macham monyet kena sambal belachan, like a monkey who had eaten prawn-chilli paste. The trouble was that drinking gallons of cold water only made the agony worse! Mak would pound her sambal belachan, or shrimp paste, with hot chilli-padi, and sumbat or stuff it into our mouths so we would never utter any bad words again. The rotan, the cane, was not the only way our parents disciplined us! But this time, she was kinder. She must have felt sorry for my loss as well, because she tried to appease me. She cooked her best bubor kachang, mung beans in coconut milk with pandan leaves. Its fragrant wafting aroma made me forget my distress. It was easy to tempt me.

On August 20, excitement was in the air.

“Chepat! Chepat! Come quick!” Abu called out. “Kapal Terbang! Aeroplane!”

We heard it too, the throbbing engine of the aeroplane flying overhead – as rare a sound and sight as a motor-car coming into our village. Children and adults raced out into the open yard to look overhead.

“It’s going to the new airport at Paya Lebar,” my father, Ah Tetia, said with authority. “The Secretary of State for Colonies, Mr Alan Lennox-Boyd, is officiating at the opening.”

My father was a bill-collector with a British firm, thus he spoke some English and he pronounced the English name with aplomb. The other villagers looked up at him in awe.

The Malay word paya meant swamp, and lebar meant wide. Paya Lebar was on the Eastern side of the island and was connected to our village by the Kallang River. My father had taken me past a swamp at Toa Payoh, the Hokkien name meaning the same as Paya Lebar in Malay. I recall the swamp’s sinister look, acres of thick, dark mud, surrounded by mangrove trees with their aerial roots, which in the half-light looked like monsters stretching out arms and long fingers. Deep-throated frogs burped sonorously across the eerie landscape. To build the new airport to replace Kallang Airport, the villages surrounding the swamp were relocated to the North of the island. As the villagers were mostly Chinese who raised pigs that were taboo to Malays, those villages were called Chinese Kampongs.

“If you are good,” Ah Tetia said to me. “I will take you to the airport to see the new passenger terminal.”

Indeed, he did fulfil his promise. I had such complex and mixed feelings about my father. He could be so volatile and bad-tempered. Yet I have stored wonderful memories of his tenderness.

That same year, my father’s fourth younger brother and his wife, who lived in Petain Road near the city, invited us to their home for Christmas. Fourth Uncle had to be addressed as Si Chik, and Fourth Aunty had to be called Si Sim. This manner of calling was very precise, so even a stranger could decipher the exact relationship of the person being addressed to the person making the address, which side of the family the uncle and aunt were from and which rung they occupied in the family; not like the modern Uncle and Aunty people use these days. In my perception, Si Chik and Si Sim were rich, as they lived in the city in an apartment block, which had running water and electricity. It was a treat to visit them as we could use their toilet, which was clean and not smelly, unlike our jambans or outhouses. Plus it had a flush system. It seemed like magic to me that when you pulled a chain, water sluiced out to wash your mess away. To wipe their bottoms, they had a roll of loo-paper, white, soft and clean, compared to the squares of newspaper we had to use. When caught in the rain whilst queuing to use our outhouses, our newspaper squares would get soggy and when we wiped our bottoms, the newsprint would come off and smear our bottoms with black ink!

My aunt and uncle had two daughters, Mary, who was the same age as me, and her sister, Janet, who was three years younger; and the youngest was a boy. As Mary and I were only months apart, I was constantly compared to her.

“Look at Mary, she’s so white and pretty. How come you’re so black? So ugly! No one will marry you!” My father said.

I can recall the young Mary clearly, with her fair skin and up-turned nose, which sniffed at conditions in our kampong when she was forced to visit at Chinese New Year. She and Janet would be in beautiful Metro-bought dresses. Metro was our local department store in the High Street, but my family could not afford any items from there. My cousins wore shiny black patent shoes and lacy socks. They were so conscious of catching something that they refused to take their shoes off. Instead they walked into our attap-hut with their shoes on. It was taboo on normal days to wear shoes in the house, and it was worse on Chinese New Year Day. But despite their father’s cajoling, they refused to take their shoes off. My aunt never visited us as she too could not bear to visit our village. I knew that my mother was pained by her attitude.

“I’ve got some money from chap ji ki,” Mak said. Like most women in the village, she indulged in a bit of gambling with the prospect of winning a windfall. The harmless gambling gave hope when circumstances were dire. The other money-accruing device that villagers indulged in was their contribution to tontine, or senoman in Malay. The latter was a kind of communal saving scheme, each person in the scheme taking turns to collect the entire pool of money when their need was paramount.

“We’ll do something nice to your hair, shall we? Wouldn’t it be good for your cousins to see we can afford to have your hair permed?”

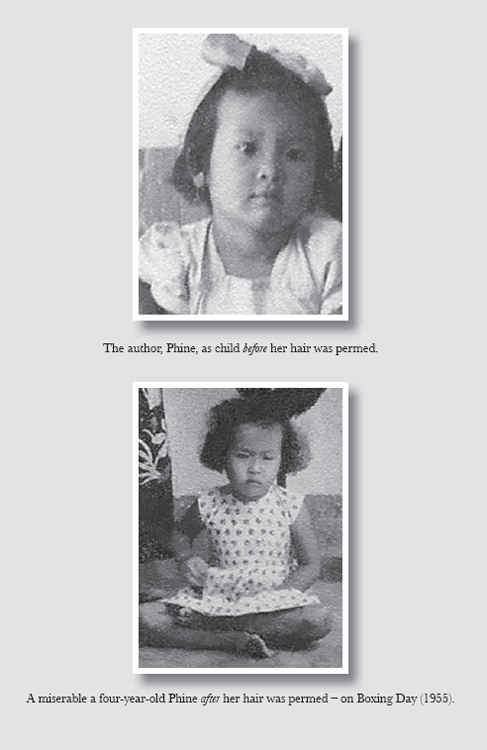

Maybe she was also trying to make amends for cutting off my long, beautiful hair. Though this was a new technology, permanent waves were becoming fashionable. European women magazines featured beautiful ladies with curly hair, some even blonde or brunette. Black and white films, with a cute little American called Shirley Temple who had dimples and gorgeous ringlets, were popular. All the village kids, myself included, could not wait for the Film-Man to bring us a Shirley Temple film. He would screen it outdoors whilst we sat on make-shift wooden benches. Every little girl wanted to have Shirley Temple’s dimples and soft curls. Little girls believed that they could get dimples if they stuck their finger into their cheeks. So you could spy children in the village spending hours poking their fingers into their cheeks! I was lucky to be born with dimples in both cheeks, but my hair was straight and rigid. As it happened, a salon had opened just on the outskirts of Kampong Potong Pasir. Mak herself always had her hair long and straight, tied up in a bun like most Peranakan and Malay women. But she wanted me to be modern. Like many mothers, she liked to treat me like her doll. I was her eldest living daughter, her other daughters had died before I was born. My sister, who was two years younger than me could not have her hair waved yet. I thought of myself looking pretty like Shirley Temple and I was excited by Mak’s suggestion.

The acrid smell of ammonia hit me as we entered the small salon. There were tall mirrors on one side of the room and women sitting in chairs, wrapped in black capes. There were posters of the beautiful Chinese actresses Lin Dai and Huang Li Li, their complexions as white as porcelain, considered by the Chinese to be the epitome of beauty. That was why I was always considered ugly as I was too black. Mak spoke to the hairdresser, her voice low and sweet as it always was.

“I’ll be back later to pick you up,” she said to me reassuringly.

I was made to sit on a high stool, my legs dangling off the floor.

The hairdresser talked above my head to the other ladies as she worked with my short hair, soaking it with the permanent wave lotion. It smelled foul and I nearly retched. It was worse than the kerosene Mak had used. I was beginning to regret having my hair permed. To console myself, I made myself think of sweet Shirley Temple and how I was going to look like her. The hairdresser took each section of my hair and curled it round a metal rod which was attached to a wire. By the time she was finished, I was like Medusa, snakes of electrical cable emerging from my head. The weight of it was immeasurable. It made my neck ache and gave me a severe headache. To my horror, the hairdresser switched on the power and the rods grew hotter and hotter – my face felt like it was slowly being cooked. The heat burned through my scalp. This was what it would have felt like if someone had indeed thrown a lighted match my way when my head was doused with kerosene! But it was not the lice which were roasting, it was me! I hugged myself so as not to cry.

It was a relief when the power was finally turned off and the heavy load was taken off my head. When my hair was released from the rods, it sprang up in all directions as if I had been electrified. The hairdresser was definitely a novice at perming hair! My new hairdo was horrible and I hated it. When my mother came back and saw me, all she said was, “Alamak!”

The hairdresser looked embarrassed. She whispered something to my mother. But she could not offer any remedies. My hair was so strong that the botched perm stayed petrified till Christmas.

I sulked as my parents took my sister and me to town to visit my aunt and uncle who lived with Lao Ee, my paternal grandmother. I couldn’t understand why she was addressed in the Teochew term of Old Aunt from the maternal side of the family, but she was worth visiting. Plus the other pleasure I got from visiting them was that I could use their toilet. Even at that age, I had the sheer tenacity and capacity of saving my bowel movement till I got to their flat – which was quite a feat! But I already suffered a severe identity crisis whenever we met my cousins because everyone said how pretty cousin Mary was because she was so white, and I was so ugly because I was so black. Apparently the Chinese have no word for brown or tanned! Now I had to meet them with my hair looking like I had stuck my head in an oven!

“Oh rambut pendek! Oh short hair. New hairdo, huh?” Lao Ee said kindly.

Grandmother was always sweet and gentle. She often sneaked a few cents to me when no one was looking. She kept her clothes in moth-balls to protect them, so when Lao Ee hugged me, she always smelled of moth-balls or of the Tiger Balm she used. I was always curious about the hard wooden pillow which she used to rest her head on. Grandmother wore the kebaya panjang like most Peranakan women her age. The kebaya was longer, hence its name, panjang, and was much looser and more comfortable than the short kebaya, so that a less-than-perfect figure could be tastefully disguised. Once her sanggul or chignon was thick and black; and on festive occasions, she would decorate it with ornate hairpins, or chochok sanggul in our language. But these days her small and thin sanggul was a sad reminder of her advanced years. Lao Ee did not make any negative comment about my hair.

But I was so conscious of my botched perm. I did not want to be seen, so I hid behind my mother’s sarong. I wanted the floor to open and swallow me whole. I’d rather be anywhere than at my cousins’ home. I hung my head in sheer despair, biting my lower lip so that I would not cry. I had to meet my fate.

When my young cousins saw me, they laughed hysterically.