TIK-TOK, TIK-TOK. The Mee Man clacked his bamboo clappers together loudly. The sound carried in the rural quietness of our village and roused us from our midday stupor. When the sun poured down its heat from directly overhead, it produced a somnambulistic effect on all of us. Even the chickens stopped their relentless scratching of the sand to dig up earthworms. But at the sound of the wooden clackers, people and domestic animals became alert, heads turned towards the sound, and the dogs’ ears went up like periscopes.

Generally we hardly heard any mechanical noise, as there was no electricity in Kampong Potong Pasir that would bring in the sound of lawnmowers or refrigerators. Even the drone of motorcars was a rarity, since transport was provided by bicycles, trishaws or bullock carts. But we would get an occasional burst of music from battery radios and the Rediffusion, a cable network that was transmitted via batteries and wires. In the mornings, we awakened to birds singing, cocks crowing, dogs barking, whilst men coughed and spat to clear their throats. The sound we heard in the village just as the sun was setting was the sound of the chattering starlings as they flew back to the trees to roost. Hens and ducks would cluck and quack as they settled into the beds of straw in their wooden coops. As darkness fell, there would be sounds of villagers pumping up their hurricane lamps, or the hissing sound of carbide lamps. There was also the clatter of enamel dishes as dinner was served on concrete floors as few villagers owned dining tables. These sounds stay etched in the folds of my memory. But the one sound that remains uppermost in my memory is the sound of the clacking of the noodle-man’s bamboo clackers.

Tik-Tok, Tik-Tok. The sound was a clarion call of hope for the hungry, for we knew that Ah Seng’s noodles were the best. Ah Seng, dressed in his singlet and shorts, peddled his noodles in a tricycle cart, which was loaded with a boiling cauldron of soup. In the cart were Chinese white bowls with their dark blue design, chopsticks and a variety of noodles with ingredients like pork slices and fish cakes. He even carried several low wooden stools so that his customers could sit by his travelling stall. When business was good, he might give a young child the job of clapping the bamboo clappers to herald his coming. Its clapping was associated with delicious food and roused people from inertia and whetted their appetites. The child also helped him retrieve his noodle-bowls after customers had finished their meal. There was no talk of child labour or exploitation during those years; if parents could not afford to send their child to school, it meant the child had to work for a living.

“Mee Tng, ten cents! Tah Mee, fifteen cents!” he called out in Teochew.

Dried noodles cost an extra five cents due to the extra chilli sambal paste and tomato sauce that was used. The taste and success of a Mee Pok Tah hinges largely on the quality of this sauce. Ah Seng’s Mee Pok Tah, Dried Wheat Noodles, were renowned. It was rumoured that as a young boy himself, he had clapped bamboo clackers for Tang Joon Teo, founder of Lau Dai Hua Noodles and had picked up the secrets of Mr Tang’s Teochew Minced Pork Mee Pok Tah. Mr Tang had plied his trade at the Hill Street hawker centre. In those days, the centre was simply a collection of itinerant hawkers who came together with their mobile stalls. They were not housed in any building and they all sat outdoors. Hill Street was not far from the Singapore River, so the food centre had the benefit of a riverside ambience. A story that went round was that Mr Tang was saved by the popularity of his noodles. Apparently during the Japanese occupation, many of Mr Tang’s customers were Japanese officers who loved his noodles. Mr Tang had been randomly selected to be executed by the Kempetai, the Japanese Military Police. Luckily before the execution could take place, one of the officers who patronised his stall recognised him and managed to get a reprieve for him.

Ah Seng parked his cart under the shade of a sprawling banyan tree so that his customers were out of the glare and burn of the tropical sun.

Like Pavlov’s dog, conditioned to react to a bell ringing, I salivated every time I heard the tik-tok, tik-tok. Chinese village children, as well as Peranakan ones like myself, ran out of our houses just to see him. Eyes opened wide at the sight of steam rising from his aluminium cauldron. Our lips smacked at its delicious aroma of stewed pork bones. The Malay children would watch from afar; for them, the smell of pork was anathema. Most times my brothers and I watched with envy as customers lined up to be served, our stomachs gurgling and grumbling.

“Not today. Maybe tomorrow,” Mak said, regret in her voice.

Then I would stick my thumb in my mouth and suck on it instead.

The sights and sounds of a rural community certainly differed from those of a city. Though our kampong was hardly more than ten miles away from High Street, which was the heart of town, we were an emotional ocean apart. The High Street was the first proper road in Singapore, having been the first to be sealed with tarmac. In 1821, the British cleared the thick undergrowth from the foothills of Fort Canning right down to the sea, which used to be on the edge of the Singapore Cricket Club until the land reclamation of 1890. The seafront promenade called the Esplanade was created with Victorian-style concrete balustrades similar to those found in the seaside town of Brighton in East Sussex, England; except that here the walk-way was lined with fan-palm trees which swayed languidly in the incoming sea-breeze. The main feature of the Esplanade Park was a beautiful fountain, its water cascading down and cooling those standing around it. The promenade was where the British and locals loved to walk in the balmy evenings to take in the sea air. In Malay, we called this makan angin, literally to eat (the) wind. When Queen Elizabeth ascended the British throne in 1953, it was renamed Queen Elizabeth Walk in her honour.

The High Street was the shopping paradise for the rich. It was the trading ground for Northern Indian settlers who ran their retail businesses and small department stores in the two-storey shophouses, supplying French lace to the expatriates, as well as clothes, fabrics and jewellery. The Europeans could have their suits and dresses tailored in silk and linen. Of course there was the Metro, a local department store. Across the Singapore River at Raffles Place was Robinson’s, a luxury department store which first opened its doors in 1858.

“I’ll treat you to a trip to town for your birthday,” my father said to Mak.

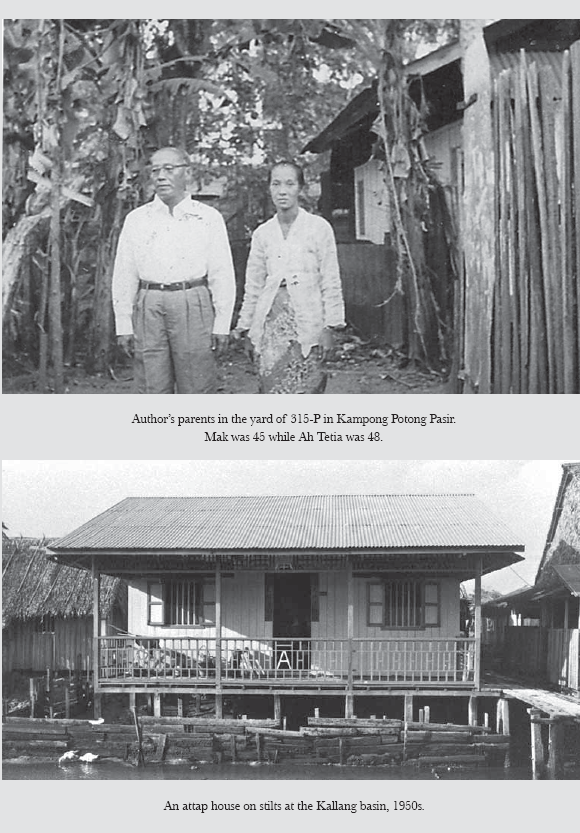

My mother’s birthday, like mine, was in March. Hers was on the 3rd and mine was on the 18th. Mak was about to turn forty-one, yet she looked as slim and beautiful as ever, always elegant in her sarong kebaya. It was rare for Ah Tetia to make any romantic gestures, so when he did, it meant he was amorous. There were only two beds in our attap-hut, one which he slept in with my elder brothers and the other was for my mother, who slept with us girls. How he managed to assuage his desire thereby spawning more children was a mystery to me. (Two sisters and one brother were born after me.)

“Oh, that will be so lovely! Can I bring Ah Phine? It’s also going to be her birthday.”

“Ya, why not? She has brought me good luck. I had a pay rise the day she was born and we were able to move from that wretched hut to this place. At least we don’t have to smell the jambans anymore.”

My parents’ first home in Kampong Potong Pasir was a small wooden cubicle with a mud-packed floor. They slept on a platform bed with the boys. The worst thing was its location right in front of the communal outhouses. They could not escape the sickening stench when the buckets filled up and the wind blew in their direction. Having meals when the smell was strong made it hard for them to swallow their food. But we still used the same outhouses, as they were the only ones available in the village, just two cubicles for so many in the village! They were the bane of my young life. I loathed their vile odour. Mosquitoes, cockroaches, lizards, centipedes and rats treated the place as their food source and recreational ground. So, when I had to answer the call of nature, I trembled with fear that the cockroaches might run over my feet or that the rats might nip my exposed bare bottom. These childhood fears became my nightmares. My mother was very understanding and would always wait for me outside the wooden cubicles in case I needed her. At night, she permitted me to use the chamber-pot so that I did not have to face the black, bristly rats in the dark.

“One day all this will pass,” she tried to assure me.

Her optimism about a better existence was my beacon of hope.

“The boys can look after each other,” my father said. “You can leave Agatha with the neighbour. We’ll walk down the High Street for you to look into the shops, maybe even Robinson’s. Then we’ll walk down the Esplanade and eat satay on Beach Road.”

Agatha was three; two years younger than I was.

I was so excited. Going into town was very special indeed. For us it was almost like going to a foreign country. Window-shopping was the best we could afford.

Watching my mother getting ready to go on an outing was a treat in itself. She selected a different kind of kebaya than the type she wore at home to do housework, normally fastened with safety pins. She chose one made of voile with pretty peonies and a phoenix that she had embroidered by hand. The material was see-through, so she wore a cotton chemise underneath. This was the main difference between a Peranakan kebaya and a Malay one. The Malays tended to match their kebaya in the same batik material as their sarong. Also the front panels of their kebaya were cut horizontally across the hip rather than tapered like the Peranakan kebaya.

Kebayas originated as an Arabic long tunic then evolved into its present shape and length, moulding itself around the curves of the female body. The Peranakans’ design was influenced by the Dutch in Malacca and Indonesia who added lace and embroidery to the kebaya. Dutch women had adapted their own long blouse to make it into an embroidered cotton tunic to suit the sweltering tropical climate of South East Asia. Malacca was a sea-port, which was an important stopover from ships from the West. The West also came to the East for tea, opium and spices like nutmeg and cloves. So it was inevitable that the Western powers fought to dominate it and to control the Straits of Malacca. First it was the Portuguese, then the Dutch, then the British. The Dutch held control in Malacca for one hundred and eighty four years, from 1641 to 1825.

Mak rummaged amongst her sarongs to retrieve her precious gold kerosang, a three-pin brooch linked by a fine chain to hold the kebaya together.

“This is the only thing I’ve got left from my previous life,” she said without rancour. She meant her life in Malacca with her rich parents. Tragedy had claimed my grandfather, and grandmother had fled to Singapore with her children. “I hope to save it for your wedding one day.”

But it was not to be. The heirlooms I received from my mother were of a different, more lasting kind.

I helped Mak comb her long black hair and she tied it into a bun. I helped her thread the creamy bunga melor buds, and she tied these around her sanggul. The natural perfume of the flowers wafted up as she glided past. She powdered her face with bedak sejok, then pinched her cheeks to redden them. It was a delightful transformation, from ordinary housewife to film-star glamour.

“You want to wear something nice as well?” she asked me.

Of course I could not go into town in my home-made shorts! Kampong kids were wild. At my age, I was permitted to run around without wearing any footwear or top. I was flat-chested and brown and could pass for a boy. Since my long hair was snipped off due to the infestation of kutu, I definitely looked like a boy.

“How about your Chinese New Year dress? The one I sewed with the full-gathered skirt and fabric rosette.”

I hated it. Mak had sewn a can-can petticoat to flounce up the skirt and its material made me hot and sweaty.

“Do I have to wear shoes?”

My feet were used to being uncased by shoes and free so my toes had spread wide and were like a chimpanzee’s feet. I could pick things up quite easily with my toes, which were as agile as my fingers. I could climb trees like a young chimp and if challenged, could even swing upside down from branches. There was a cherry tree in the sandy forecourt of the village shophouses and I climbed it often to pick the cherries. I had feet like a monkey’s, no wonder my father kept saying that there would be no marriage prospects for me. If I had lived in China, they would definitely have bound my feet! Dainty feet were synonymous with beauty. (This could only be proclaimed by a man!) Mine were far from dainty. I used to be able to hold a piece of chalk with my toes and draw with it! This meant that trying to fit my feet into tight shoes was excruciating.

“You certainly can’t go into town barefoot!”

It was a case of enduring the pain or not going into town. So I force-squeezed my feet into my narrow Chinese New Year shoes, which were tight black pumps. They hurt. I would have preferred to wear what my mother was wearing – kasut manek, the traditional Peranakan sandals with glass bead panels which she sewed herself. We spent our evenings embroidering or sewing manek. Mak used an old-fashioned wooden frame to hold the material for her bead-work. But sewing by candle-light for years took its toll on hers as well as my eyesight. The manek-shoes were her going-out footwear as she normally wore char kiak or wooden clogs when she went about in the village. The Malays called the wooden sandals terompah. In this instance, Peranakans used the Chinese and Malay term interchangeably. Most times, if we used a Peranakan or a Malay term for something, it meant we may not know the Chinese equivalent. I never understood why this was so.

My father wore a plain white shirt with his trousers. He never wore his sarong outside our kampong. Just as we were about to leave, his friend Ah Gu came rushing into our attap hut.

The names people give their children! Gu is a cow in Hokkien. Fancy calling your child That Cow! Ah Gu was a neighbour who became my father’s companion in the evenings. They usually sat outdoors after sunset, drinking their favourite tipple, a pint of Guinness, whilst they discussed politics.

“Have you heard?” Ah Gu said excitedly to my father in Teochew. “There’s going to be a rally at Kallang Airport on March 18. Chief Minister David Marshall is going to address the people about our country’s self-rule. Shall we go together? There’s a campaign right now to collect signatures of people who want independence. I’m signing. Will you? I think it’s right that the chief minister is pushing for us to manage our own internal security...”

“Ah Phine will be five on that day,” My father said. “Of course I will sign the petition for independence and go with you. Just because I’m earning a living in an English company and have good bosses doesn’t mean I want to be under their rule forever.”

“Independence is the only way to go now. You know I respect Chief Minister David Marshall a great deal. He’s trying to resolve this issue about the Chinese-educated. People like me.” Ah Gu said. “The colonial government doesn’t recognise our education. Our qualification can’t get us into university here. He sounds a clarion call of hope for us...”

“Yes, I know it’s tough for Chinese-educated people like you. But the problem is not so straightforward, because of the Chinese schools’ involvement with the communists...”

“Not all Chinese-educated people are pro-communist, you know,” Ah Gu said in an offended tone.

“I know. I know. Look. We’ll talk another time. I’m taking my wife and daughter out to town.”

The rally that Ah Gu was talking about was to take place at the Old Kallang Airport. Up until a year earlier, it had been Singapore’s civil airport. Though there had been air-strips on the island, they were mainly built for military purposes, but the first commercial aeroplanes flew out of Kallang Airport.

In 1931, Governor Sir Cecil Clementi had said, “I expect to see Singapore become one of the largest and most important airports of the world. It is, therefore, essential that we should have here, close to the heart of the town, an aerodrome which is equally suitable for landing planes and sea planes; and the best site, beyond all question, is the Kallang Basin.”

The mangrove swamps surrounding the basin were filled and land was reclaimed from the sea. Kallang Airport was born and officially opened on 12 June 1937 by the British Governor at that time, Sir Shenton Thomas. The terminal building and hangar were beautifully designed in art deco style, similar to the design of the oldest civil airfield in England, Shoreham Airport in West Sussex. It had a grassy landing zone and a slipway for seaplanes. For many years, Kallang Airport was considered the “finest airport in the British Empire.”

A week after the airport opened, a historic event took place. World famous female aviator, Amelia Earhart, flew in from Bangkok on her second attempt to fly around the world. She was accompanied by her navigator, Frederick Noonan, and they were on their way to Bandung. Her aeroplane, the Lockheed Electra10E landed at Kallang Airport, which she called “an aviation miracle of the East”. Sadly, it was just a few weeks after this, on 2 July 1937, that she disappeared. She was last heard from about 100 miles from the tiny Pacific atoll, Howland Island.

With the opening of Paya Lebar Airport in August 1955, the historic Kallang Airport also disappeared as such, for its operations as an airport ceased and it became a centre for the Singapore Youth Sports Council. This was where the David Marshall rally was to be held.

It felt like a long walk from our house through the dusty, pot-holed village road to Upper Serangoon Road. The sun was beating down on us and my Chinese New Year dress with its can-can petticoats irritated my skin. My shoes were having a jolly time biting my feet. If it were not for the anticipation of seeing the High Street and all its shops, I would have preferred to be topless and without shoes and to stay at home. I was such a peasant! My parents and I walked past the fish ponds where the Chinese men were shouting out in a kind of musical rhythm as they pulled up their nets. The bulging nets were poised in the air for several minutes, heads of fish poking through the nets, their round eyes appealing for last minute reprieve. But none came, and their mouths opened and shut, opened and shut in silent screams.

We boarded a trolley-bus to town, its thick overhead cables slithering like air-borne snakes, forming a network with other snakes at the junctions of roads. Every now and then the bell went ping! And the bus would shudder to a stop and some people would alight hastily whilst others boarded. I was delighted by this sound and waited in anticipation for it to happen next. Ping! Ping! Ping!

“Watch for this, watch for this,” Mak said to me. “There’s Tekka market where we go to get special things when Ah Tetia has his bonus. And soon we will go across the big Rochor Canal. It’s like a river.”

Mak hoisted me up so that I was off my bottom and she placed me onto my knees on the bus seat so that I could peer out of the window. Indeed, as the bus clambered across the stone bridge, I could see the water flowing. It was a strange river to me, not as wide as our Kallang River in the village and it did not have muddy or moist banks either. Through the open windows of the bus, the sounds of the city were so different from the sounds in our kampong, clamouring to be heard, exciting yet daunting.

We passed my uncle’s home in Petain Road where he lived with his wife and family and my grandmother, Lao Ee. Their apartment was in a four-storey block. For me any building made of brick or concrete seemed wealthy compared with the attap-roofed huts which in our kampong were made of rough planks of wood, crudely painted with kapor, limestone; so badly constructed on the cheap that there were gaps in the walls where you could peep into your neighbour’s house. A Chinese hawker woman wearing her samfoo, trouser-suit, carrying two baskets slung on a pole on her shoulders, was at the foot of the block of flats calling out, “Ang Ku Kuih, Ang Ku Kuih.”

The dessert she was selling was made from glutinous flour stuffed with softened yellow mung beans. The glutinous paste was coloured red and pressed into a turtle-shaped mould, hence giving it its eponymous name, ang ku, which was Hokkien for Red Turtle. Because of its vibrant colour and the symbolic meaning of the turtle, which stood for prosperity and longevity, this cake was served at auspicious Chinese ceremonies like weddings and Chinese New Year. The sweetened mung bean paste was designed to bring sweetness into one’s life. The Chinese were very concerned with symbols and so Peranakans too adopted the ang ku kuih as their own, as well as the love of symbols and meanings. Not adhering to certain symbols or customs was taboo, which made Peranakans very pantang, the Malay word for superstitious.

Adults and children rushed to their balconies when they heard the hawker-woman’s cry. A young girl shouted out from the second storey to catch her attention. The hawker put her baskets down and looked up. They had a brief discussion, presumably on what the young girl wanted to purchase. Then the young girl placed some coins in a small rattan basket and lowered it with a rope in the same way that we lowered a pail into the well. The hawker woman pulled down the basket, took the coins, then placed the ang ku kuih in the basket and the young girl drew it up towards her. I had never seen anything like it before as we all lived on the ground floor in the kampong so did not have a need for this system. The contrast of city to village was fascinating.

At Dhoby Ghaut, an area between Selegie and Bras Basah Roads, the small wood of trees was strung out with flags of washing flapping in the wind. I knew that dhoby was the Hindi word for laundryman, since many of the laundry-men were Indians. People must be rich to have someone else do their laundry for them, I thought.

“Look, Ah Phine,” Ah Tetia called out. “That’s the Cathay Building, the tallest building in Singapore.”

The four-storey building was imposing. It was completely made out of concrete, not a piece of wood or attap in sight. I thought to myself, “I bet they have flush toilets like my rich cousins.”

At the junction of Bras Basah Road, a traffic policeman in his khaki shirt and shorts, wearing a pith helmet, waved his arms about in order to direct traffic.

“Bras Basah is a corruption of the Malay words beras basah, wet rice,” my father said to Mak. “There’s a Malay legend that it was named after the incident when a barge on the Singapore River carrying sacks of rice had overturned, causing the wet rice to spill onto this area.”

My mother was impressed.

Town was a magical land of robust buildings and landscaped gardens, with colourful orchids, bunga raya hibiscus and bougainvillea. The roads were tarmacked and there were street lamps. I imagined that when the electricity ran through the wires, the lamps must light up with joy. At nights, our lorongs in the village were shrouded in darkness, instilling in the children a fear of ghouls and Pontianak, the legendary Malay female vampire and spirit-familiars called polong. Our attap roofs were rigged with cactus plants so that their thorns would snag at the long hair of pontianaks and polongs when they levitated and flew over our houses, according to popular belief.

There were variations as to how the Pontianak came about. There was actually a village in Pulau Pemanggil, near Mersing, which was named after her. People said she resurfaced after her death to take revenge for her death. Some said she was killed. Some said she died in child-birth. Some said she lived in banana trees, others said she lived in the chempaka trees. Some said she had long hair and long fingernails and loved fish. Some said she loved to devour new born babies. Others even said she loved to suck the blood of men. But all agreed that she took on the form of a beautiful woman until she found her victim, before showing her ugly wizened self. A polong, on the other hand was said to be a personal spirit kept by someone who indulged in black-magic.

Ping! I was startled by the sudden sound as my thoughts had strayed to the Pontianak and polong. My father had pressed the bell.

“We’re there. It’s time for us to get off.”

I practically leapt off the last step of the bus, leaving all thoughts of evil spirits behind. Surely neither a Pontianak nor a polong could survive in the city, with all its electric lights?

High Street was a different country! The grand Adelphi Hotel stood at the corner like some great matriarch looking down at the more humble shophouses and five-foot ways. Saint Andrew’s Cathedral, regal and imposing, sat in a verdant landscape of lawn and trees. There was such a burst of colour and light as we strayed into various shops. My mother held my hand tightly and when she was fingering a bolt of fabric, she pressed me close to her sarong. I stood amongst a thicket of legs, afraid to get separated from my parents. I could hear my mother’s sighs of contentment and I knew she was happy even though she did not buy anything. And I knew my father was happy too because for the first time, I saw him holding Mak’s hand. When we peered at the elaborately dressed windows of the shops, they stood pressed hip to hip. Glass window-panes were a novelty to us, as the windows in our village were wooden shutters.

“Wait till you see the toys at Robinson’s,” Ah Tetia said to me.

My heart pounded in anticipation. I could feel my feet squashed to death in my shoes but I gallantly walked without whingeing because I wanted to see what toys from a store looked like when they were new. Any store-bought toy I had so far, came from the dustbins of the English children from Atas Bukit, at the top of the hill above our village. Most of the time, we had to make our own.

My father did not feel comfortable in taking us into Robinson’s itself, as its customers were all richly dressed and were mostly angmoh, Europeans. We just gazed in awe at its magnificently dressed windows resplendent with wonderful things. We pressed our noses so close that our breath steamed up the glass panes. My mother oohed-and-ahhed over the beautiful crockery and home items and I held my breath at the sight of gorgeous dolls with blonde hair and blue eyes, large cuddly teddy bears with fur, a toy train whizzing along its tracks set in the verdant English countryside. I noticed that the uniformed doorman was watching us critically, perhaps wondering whether to tell us to move on. This subtle disapproval of our circumstance was something I became more aware of as I grew older. Poor people were like a bad smell to the rich or a disease that they might catch.

“Come on,” my father said, conscious of the doorman’s looks. “Let us walk through Change Alley and then we will go and see the fountain at the Esplanade.”

It was going to be a fair walk from Raffles Place to the Esplanade so I asked, “Can I take my shoes off ?”

“No!” my father said sharply. “Do you want people to regard you as ulu?”

Ulu was Malay and Peranakan for a place that was remote, but it also referred to someone who acted naïve, at worst stupid, like an ignorant country bumpkin. A similar expression in Hokkien was Sua Ku, Mountain Turtle. It was the ultimate insult. Though he did not show it earlier, my father’s feelings must have been rankled by the doorman’s attitude, causing him to lash out at me.

Fortunately Ah Tetia’s dark mood evaporated as quickly as it had appeared. He held my hand tightly as we pushed through crowds at Change Alley, which was a street bazaar that had all sorts of peddlers with colourful crafts, saris and costume jewellery. There were many Indian Money Changers, which must have given the street its name. My father walked us down Cavenagh Bridge and down to the seafront Esplanade Park. As he worked in an English company, he was a fount of information about the English and the buildings they re-created here in Singapore to reflect their own. Also he loved to show off to Mak, pointing out this and that to us – places like the Fullerton Building, which was the city’s main post office. At the park, he stopped by a magnificent tiered water-fountain in Wedgwood Blue, decorated with statues of nymphs and cherubs, water spouting out from the mouth of a gargoyle. The sound of cascading water was lovely. My father gesticulated with his hand.

“This is Tan Kim Seng Fountain.”

“Who is Tan Kim Seng?” Mak asked.

“He was a Peranakan philanthropist who donated $13,000 in 1857 towards building Singapore’s first public waterworks so that people could get fresh water in town. Of course it has not been piped down for us to use in the villages yet, but one day it will. That’s what our local politicians are promising us anyway.”

“It will be a small miracle for us to be able to turn on a tap in our houses and have water flow out of it. We won’t have to cope with drawing water out of a well, nor suffer when the rains don’t come and the well dries up. Our lives won’t be dictated too much by the weather.” Mak said with a sigh.

Despite his earlier retort, my father lifted me up and helped me stretch out my arm so that I could reach out to wet my hand under the falling water. It was rare to share moments of tenderness with my father or have such close physical contact with him, so my experience was intense. It was a treasure that I saved as a golden nugget of memory. Things like my mother’s kerosang or sireh box could be preserved as heirlooms but the best heirlooms I saved were memories of my family.

“These statues all look so angmoh,” Mak said. “Their features are not Asian at all. The fountain must have been built by someone English.”

“You’re so perceptive. You make observations like no one I know.”

My father was in an amorous mood. Otherwise he would not have complimented my mother. I had never heard him say anything complimentary to her before. The perfume from the flowers in her hair must be going to his head. Or maybe her sexy see-through kebaya had something to do with it. Suddenly Mak became all coy, smiling and lowering her head.

“The person who built it was Scottish. Scots. Whatever,” he continued. “His name was Andrew Handyside. He was born in Edinburgh in Scotland. He was famous for making ornate bridges, railway stations, market halls and fountains all over the world. This fountain was made in Derby, England, at his Duke Street Iron Foundry. It was initially installed at Fullerton Square in 1882 but was moved here in 1925.”

Other people standing near the fountain heard my father speak and they turned to look at him, their faces reflecting that they were impressed by his wealth of knowledge. They turned back to examine the fountain with new eyes.

“You’re so clever,” my mother whispered, returning his compliment. They were definitely in the mood that day. “I don’t know how you can know and remember all these things. Working at William Jacks has been good for you.”

William Jacks was an English general merchant company that sold things like weighing scales. The company had its premises in Bukit Timah. My father was their bill-collector. But I was not interested in my parents’ conversation. I was too preoccupied running round the fountain and playing with the water to see them exchange knowing glances. They must have been pleased to have uninterrupted moments to themselves as I busied myself with the fountain and skipping up and down the park. I was no longer tormented by my tight shoes, I was so happy.

“Are you hungry yet?” Ah Tetia asked.

“Ya-lah!” I cried out enthusiastically.

Talk of food always had the power to capture my attention. I was already having such a wonderful day and to have something to eat as well would crown the day. We traversed the length of Queen Elizabeth Walk, the breeze ruffling my hair. Cautiously, my parents let me stand between the stone balustrades to look down at the waves lapping against the sea-wall. I felt a huge unnamed yearning when I saw the sea spread out in ripples before me, the horizon a distance away, the fluffy clouds in the late afternoon sky. I would have loved to know where in the world the waves had been. The smell of salt in the air lifted my spirit.

So too did the smell of satay roasting outdoors on their burning charcoal beds.

“This is Satay Club,” my father announced when we got to Beach Road. “Well, it’s not actually a club but the hawkers are all satay sellers and they group here, so it’s like a club.”

Rows and rows of Malay men squatted beside their stalls, roasting the wooden skewers of marinated mutton, beef and chicken over burning coals. Some roasted the intestines of cows as well, called babat in Malay. The hawkers had come from afar, from the many kampongs, carrying their wooden stalls on sturdy rattan poles so their bare brown arms were sinewy and muscled. Like Ah Seng, they even carried low stools for their customers to sit on. The aroma of the satay was mouth-watering. Each time a satay-man spread oil on the satay, there was a lively eruption of orange and blue flames. As the brush he used to oil the satay was made from sheaves of pandan-leaves tied together, its contact with the raw flames scorched the leaves and sent the delicious fragrance of aromatic screw pine leaves into the air. He fanned the flames with his palm-fan, making the flames grow larger, dancing wildly.

“Let’s sit here,” my father said, drawing a low stool for Mak to sit on.

He acted very gentlemanly that day. My father ordered lavishly. He was giving my mother and me a specially good treat. I was in my element, dipping the barbecued satay and squares of ketupat, rice-cakes, in the spicy, crunchy peanut sauce. I did not care that we were sitting by the roadside, the fumes from the buses and cars mingling with the smoke from the fire, the sound of their engines loud in our ears. I was strangely unperturbed that a few yards away the rats were poking their heads out of the monsoon drain, taking their chances by scuttling amongst peoples’ feet to steal a morsel or two. As the day darkened, the flames from the barbecue pits seemed to roar with more gusto, their bright colours brightening up the evening.

That night my feet were red and sore and they throbbed. But I was so exhausted from the day’s activities that as soon as my head touched the pillow, I started to drift off. I was vaguely aware that in the darkness, my father had made his way into my mother’s bed.

My mother woke me up on March 18 with the traditional Peranakan birthday snack of sweetened mee sua with a boiled egg in it. She had got up early to prepare it. As I took the first mouthful, I nearly spat it out as it was so sickly-sweet.

“You have to eat it all if you want to have a better life!” Mak said. “The sugar is to bring sweetness and good fortune. Hopefully our circumstances will change and your future will be brighter and never again will you have to live in the conditions we have here. The boiled egg is a symbol of fertility so that you will have children to take care of you in your old age. The long strands of noodles are for your long life.”

Who would dare to thwart the God of Good Fortune when put like that? So I forced myself to eat the gooey mee sua. Then Mak gave me an ang-pow, a red packet with some money in it, the red colour symbolising good luck, and the money for prosperity. There was 80 cents in it, the number eight being another Chinese lucky symbol. Eighty cents was a lot of money for me. It could buy me eight bowls of Ah Seng’s mee tng. Not that I’d spend it all on one thing.

“Can I use it to buy myself a ribbon, Mak?”

“Okay. Don’t spend more than ten cents though.”

So off I went to our village shops; some of them were just wooden lean-tos. Mak Boyan selling her delicious bee-hoon and Ikan bakar, Samy with his ice-ball, Ah Sim with her boiling cauldron of turtle eggs, which we ate by sucking it out through a hole punched into its end. Kakar at the corner was an Indian shop which sold a plethora of interesting things. The moment one entered the shop, one could smell the fragrant spices piled up in gunny sacks. He sold rice, lentils and other cooking ingredients as well as useful household items like brooms and batteries. Kakar’s shop was like an Aladdin’s cave. I knew he also sold wheels of brightly coloured ribbons.

“It’s my birthday and I have 10 cents to buy a ribbon,” I announced to Kakar proudly, showing him the money in my palm.

“How old are you today then?”

“Five,” I said, trying to sound grown-up.

“What a lucky girl you are. Which colour would you like?”

He reached out and brought down the box of ribbons for me to select. There was a whole rainbow of colours and it was so difficult for me to choose. Finally I chose yellow.

“Normally for ten cents, I give you ribbon in twelve inches,” Kakar said in the way Indians talked. “But since it’s your birthday, I will give you extra.”

I was so delighted that I skipped all the way home. I would have recalled that day with joy if not for the disaster that followed.

Several of the villagers were going to the All-Party Merdeka Rally at the Old Kallang Airport. People were keen to attend to find out how their lives could be improved. Ah Gu came for my father and they left together with Samad, Abu’s father and our neighbour Gopal. A six-member British Parliamentary delegation from London had arrived and the rally was organised to show the British that Singapore wanted independence; merdeka in Malay. Twenty five thousand people attended the rally. These were mostly men.

We heard all about it when our villagers came home. Several were injured, some maimed. Wives and mothers, including Mak, rushed out of homes to greet them, and found them hobbling, their faces bruised, arms bloody.

“What happened?” Everybody asked at once.

“There were thousands of people...” Samad said.

“Yes, pushing and shoving,” said Ah Gu.

“Carrying placards and banners that asked for merdeka,” Ah Tetia said.

“Then Chief Minister David Marshall invited us to go on the stage to raise our arms and shout merdeka. We thought it was a good idea so we went up,” said Gopal. “There were so many people jostling up there with us on the stage. Then there was a creaking sound, the stage moved and then collapsed. People were piled on top of each other, squashed like sardines...”

“It was chaos after that...” Samad said.

“Luckily we got out alive,” Ah Tetia said.

“Luckily the Chief Minister was not hurt either. He was whisked away by security men...” said Ah Gu

“Was anyone killed?” The villagers asked.

“We don’t know. We just tried to escape.” Gopal said. “There were ambulances, fire-engines and police.”

The Straits Times reported the next day that fifty people, including twenty policemen, were seriously injured. Sadly the incident did not help Chief Minister David Marshall’s reputation with the visiting British Members of Parliament (MPs). They doubted the Marshall government’s ability to control internal security. Disillusioned that he had failed in his attempt to get self-government, David Marshall resigned and Lim Yew Hock succeeded him as Chief Minister on June 8. It was now up to. Lim Yew Hock to sound the clarion call of hope for the people.

“Ah Gu and I are going to the opening of the new Merdeka Bridge. It’s not any old bridge but is a symbol of our country’s aspiration for independence. Would you believe that the word merdeka was actually suggested by an angmoh, Mr Francis Thomas, who used to be a teacher at Saint Andrew’s School but is now Minister of Communications and Works? The ceremony will be on August 18. Do you want to come?” Ah Tetia asked my mother. “It’s an important occasion for Singapore. The new bridge is constructed over the Kallang Basin to link the two stretches of the new Nicoll Highway so that we can get from the City to the East Coast more easily.”

Mak was pregnant again. It was a regular situation for her every other year. But this time, it was the consequence of the March birthday treat. The baby was due in December. She accommodated her growing belly by letting out her sarong.

“I’m already five months now. Better not.” Mak said.

“I’ll take Ah Phine. There’s bound to be fireworks and other displays. She’ll love it.”

I was so glad he took me. The bridge was magnificent. It was 2,000 feet long and 65 feet wide. Thousands of people turned up to celebrate. My father carried me to squeeze past the huge crowd. It was late afternoon, so the sun was not too strong and the shadows from the Casuarina trees with their fine needles were already falling upon us. The pageant would end at sunset, just in time for the fireworks display. Ah Tetia lifted me onto his shoulders so that I could see. It was another of our intimate moments for me to treasure.

At the entrance to the bridge stood a tall monolith with two lions back to back against it. The stone lion, designed by Italian artist Rodolfo Nolli, was named the ‘Merdeka Lion’. We did not have independence yet but it was named in the hope and anticipation of independence. Everyone felt a strong sense of joy and pride. There was a promise of hope in the air – that one day, we would truly be free to rule our own country. It was the first stirrings of a feeling that would grow into a cohesive force that would form our future nation. All the ethnic communities contributed something for the major event. The Chinese staged their usual dragon dance and fired thousands of fire-crackers, their exploding sound like a stampede of cows’ hooves; their splintered paper raining down over our heads in a shower of red. The Malays, dressed in traditional outfits, presented a koleh procession, rowing their narrow boats or koleh across Kallang Basin. But the most memorable for me was the Indian community’s contribution. They had chartered a small aircraft whose engine droned as it flew over the river mouth. The small plane swooped over the newly inaugurated Merdeka Bridge and then in a breathtaking display, the people in the plane threw out rose petals which spiralled downwards like confetti all over the bridge and all over us. It was truly spectacular.