TYRANNY COMES IN many shapes, colours and forms. The tyrant controls and wreaks terror amongst those he tyrannises. Its might could force people to cower, or it could rouse the community spirit and make people stick together and fight in self defence. For a few weeks, our village had been clutched by fear – a tyrant slid amongst us, killing those in his wake; and no one could catch him. Fortunately, so far he had not attempted to kill any humans. But the history of behaviour of his kind had taught us that his proclivity could change.

Beyond our kampong – clusters of wooden huts with thatched attap-roofs that were arranged around a maze of narrow lorongs or passageways – lay wide fields of wild grass called lallang. The stiff, tall grass, some taller than a child’s height, had razor-sharp edges and could nick your bare flesh, drawing blood.

And yet those same fields could be inviting, swaying languorously in the breeze, as if waving to adults and calling children to venture into them. The area held a kind of allure for those who were adventurous. It was a place for catching fish and eels, even frogs, which the Chinese called Chwee Kway, Water Chicken, and loved to eat. The grassland was also a playground for the fertile imagination, where heroes and pirates brandished their swords. The Malay kids pretended to be Hang Tuah or Hang Jebat or cowboys and Red Indians, leaping over wetlands populated with blood sucking leeches, fashioning arrows from the spine of coconut leaves and bullets from cuts of thick vines. Some folks said that this was where fairies and ghosts like the pontianak hide. The mood of the place could change with the weather, sombre and frightening when dark, delightful when sunny. Butterflies flitted back and forth, creepers of morning glory with their purple bell-shaped flowers festooned across shrubs and trees, giving the grassland an aura of pastoral bliss.

What was more important to the villagers was that the grassland was an Aladdin’s cave of food. For those with an expert eye, food could be found in its undergrowth and vegetation, in its ditches and ponds. The assam or tarmarind trees grew there, their brown pods hanging down invitingly. Many of our local dishes used tamarind as a sauce or base, so the pods never stayed long on the tree. Children swam in the pond for fun, or to catch fish and eels. One of the plants that grew there in wild abundance was a root vegetable, tapioca, or ubi kayu in Malay. My mother, Mak, like many of the villagers, had devised many recipes from its tuber and its leaves. Peranakans were reputed to have the knack of creating exotic dishes from the most ordinary of ingredients. And my mother was a Peranakan cook par excellence.

During the days when we hungered for something more than boiled rice with soya sauce, she would send my elder brothers into the grassland in search of tapioca.

“Go carefully,” she would say to them. “Beware of the snakes, huh. Pick what you can. We will make lemak with the tapioca leaves. Make sure you pluck the younger shoots because the older leaves will be too fibrous to chew.”

Mak’s lemak was made with rich freshly squeezed coconut milk, ground chillies, onions, lemon grass, buah keras or candlenuts and the fragrant limau perut or lime leaves. It was a soupy kind of dish and the tapioca leaves were boiled in the spicy soup. When my father, Ah Tetia, got his Christmas bonus from the English firm where he worked, we might have the luxury of fresh prawns to add to the lemak. The prawns would give the gravy that special sweetness which fresh seafood had the capacity to do. We never took for granted the food that we had the good luck to eat.

Though hidden from common view, the lallang grassland had a thriving population of wild rodents, salamanders, frogs and snakes. Nesting birds also made the lallang their home and their refuge. Though they might be a source of food for some people, Mak would never permit us to kill a bird for that purpose.

“They herald the sun with their birdsong, and bring joy,” she said.

When desperate, we might steal their eggs, but we would not slaughter them for meat. For I too knew the joy my mother spoke of. My heart swelled with happiness if I beheld the sight of a wild bird, a white egret with its long beak, patiently waiting to catch a fish, the kingfisher flaunting its shimmering bright colours in flight, or a long-tailed lime-parrot winging its way back and forth amongst the trees. My mother was a very special lady indeed and for a simple kampong woman she seemed to sprout all kinds of thoughtful sayings. I saved them like precious heirlooms, locked safely in my heart.

Rural folks still owned the uncanny knowledge of sourcing food and medicine from nature. They knew which plants, seed or bark to eat and to use for medicine. Except for the disgusting cod-liver oil which Ah Tetia made us take each morning, all our medicines came from nature. Our village bomoh or medicine man, Pak Hassan, called the wilderness his pharmacy. He was a natural homeopath. My mother too had his unique gift. Both of them worked from their intuition and sometimes they would discuss the best folk remedy for this or that ailment. A neighbour came to her once with his foot almost severed from its ankle and she bound it with crushed dokong anak, a herb she found in the fields.

“You’ll go to prison one of these days,” my father warned her. “You might kill someone with one of your concoctions. You’ve no education and no learning. Don’t act like a doctor.”

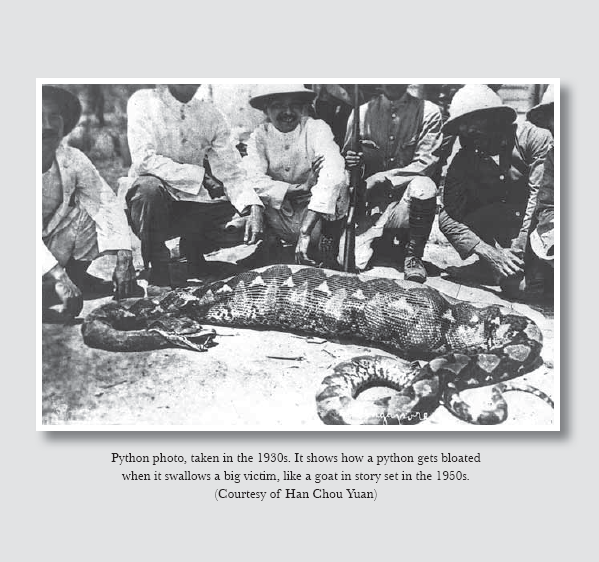

But amongst the plethora of goodness that lay in the grassland, our tyrant lay in wait. Camouflaged. Hiding. It was the python, a snake indigenous to the tropics. No one had seen him yet but the evidence of his presence lay in his wake, clusters of feathers left behind by chickens and ducks he had swallowed, a track of dried leaves and dirt pushed aside as he slithered past; lallang and undergrowth flattened out by his weight.

“The Ular Sawa is about ten-foot-long,” village python-expert, Pak Osman, declared. Ular Sawa is the Malay term for a python. Our village was a Malay kampong as opposed to Chinese kampongs, which reared pigs. “See how wide apart the debris is here? That’s the width of his body.”

He used the Malay pronoun dia-, to describe the python. This pronoun refers to both genders, so unless heard in context, it was sometimes difficult to know if a person was referring to a male or female. Pak was short for bapak or father, and was used as an honorific to address older men politely. Like many of the men living in the village, Pak Osman’s cinnamon brown chest was bare, and he was clad only in a check sarong. The elders of the village, all old Malay men, followed Pak Osman’s fingers pointing to the ground. There, drawn into the sand and mud was a trail that suggested the python’s length and his swaggering gait.

“Ya, Allah! Oh my God!” One of them wailed. “He seems big enough to swallow a child then.”

“No doubt about it. A python can certainly swallow something the size of a goat. Its jaw is mobile and can open very wide. He has special bones that act like a hinge. When he’s swallowing something large, his windpipe thrusts out like a snorkel so that he can still breathe. His skin is stretchy, that’s why he is able to expand. We must warn all the villagers not to go into the grassland until he’s caught. That’s where he must be hiding.” Pak Osman said.

“Pak Osman, how does the python kill his victim? Does he chew it to death?”

“No, lah! He doesn’t chew it, though his teeth are curved backwards so the victim can’t escape once it’s within the jaws. First the python coils himself around the victim. Then he squeezes the victim, breaking its bones to deflate the bulk. When the victim exhales, the snake increases the pressure until the victim’s heart stops. Then he swallows it whole.”

“Ouch!” Someone exclaimed.

“We have to spring a trap,” Pak Osman said. “We have to catch him when he’s just eaten something big. He will then have difficulty in moving for a while until the victim gets digested. That’s the time to get him. Meanwhile we have to make pitchforks that we can use to anchor the length of his body to the ground whilst someone hacks him to pieces with a sharp parang.”

“The python must be evil.”

“No, my child,” Pak Osman explained kindly to the girl who was my friend Fatima. “The python is not evil. Its nature is to survive, just as we human beings need to survive. If he stayed in his own environment and did not bother us, we wouldn’t have to kill him. It is because he has encroached on our freedom that he has become a tyrant and has to be eliminated.”

“So a tyrant is someone who takes away the liberty of another person?” Fatima’s elder brother, Abu, asked. But Pak Osman was too preoccupied to respond.

“No one should go near the grassland until we catch the python!” The warning was issued all around the village.

“What’s a python?” I asked my mother. After all, I was only six.

“It’s a giant ular,” Mak said.

“Does it mean we’re not going to get any tapioca? I want some baked tapioca. I want some baked tapioca.” I grumbled petulantly.

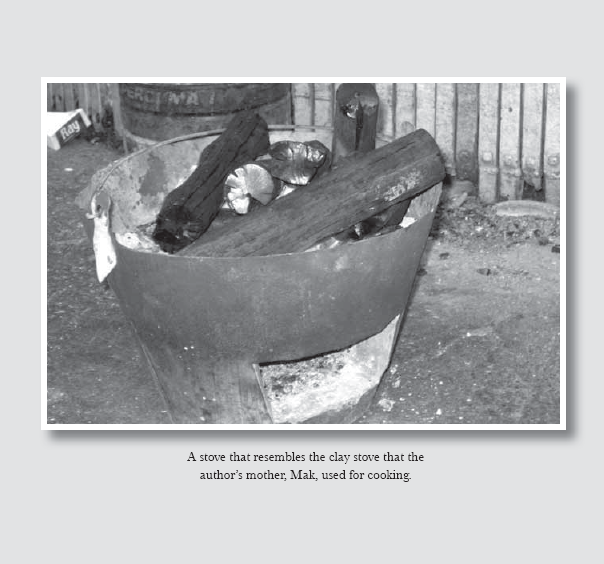

My mother made the most delicious kuih bingka ubi, baked tapioca. She would grate the tapioca tuber and coconut finely, then mix it with gula Melaka, raw palm sugar. She’d press the mixture into a pan, then bake it in her improvised oven over her charcoal stove. When cooked, the top would be a rich golden brown, and crusty, whilst the inside would be moist and crumbly. It was mouth-watering. My mother made cooking an art.

“We can go and dig up tapioca another time. But when the snake is caught, the elders will distribute the meat and I will make python steaks for you. Or we can have a barbecue or python satay.” She said.

“Python satay, python satay,” I sang.

“Don’t go out at night,” Pak Osman stopped by to tell every household. “The python has poor vision, so it uses its unique infra-red sense. Therefore it can navigate perfectly in the dark. That’s the time it will feel safe to come into the village grounds.”

“Lock your chickens properly in their coop!” Someone shouted.

There was no ceiling across the wooden rafters underneath the attap-roofs, so voices could be heard along the terrace of houses. Every time someone dropped a dish or glass on the cement floor, its clatter echoed throughout. At night, people muffled their moans and lowered their groans.

“Don’t forget to lock your children in too...” Someone added.

“And your wives,” a male voice said. “Or maybe not...”

Somebody guffawed in response. Then a loud smack was heard. His wife must have shut him up. It was not easy to keep secrets, living in a kampong.

Fatima and Abu came round to our house, full of excitement. Fatima was nine, a pretty girl with skin that glowed with a deep copper-tone tan. Abu, now fourteen, was the village whiz-kid at chapteh. They came from a family of twelve. Nearly every family in the village had more than ten children, many of them sleeping on one bed.

“Ah Phine, my father’s taking us up-country!”

“Wah! Up-country to Tanah Melayu?”

“Yes,” Fatima enthused. “Where we can see mountains and rubber plantations.”

“My brother took me once to Batu Tinggi to see the tall waterfall.”

“Oh, there’re lots more waterfalls much higher than Batu Tinggi,” she said.

My mother’s family had come from that country, from Malacca on the West Coast. Peranakans were largely known as either Malacca or Penang Peranakans. As both these places and Singapore used to be called the Straits Settlements, people called us Straits Chinese to differentiate us from the Overseas Chinese, who kept their own culture and customs. Peranakans integrated both the Chinese and Malay cultures.

“Is your father taking you away because of the python?”

“No,” Abu said. “There’re lots more pythons in the jungles up there. People don’t worry about them unless they attack. Bapak is taking us to visit our grandparents. They live in the big bandar, Kuala Lumpur.”

I remembered Mak telling me about the mountains in Malaya. We spent most evenings in the light of the hurricane lamp or carbide lamp sitting on our cement floor whilst we embroidered chemises or beaded slippers to sell. She had taught me the Peranakan crafts as soon as I could thread a needle. She loved telling me stories of her previous life, which I stored carefully in the pages of my memory. Sometimes she would allow herself a treat and chew her sireh (betel leaves) as we worked. Her wooden sireh box, or Tepak Sireh, was a poor replica of the one she had in Malacca, made by Malaccan craftsmen when her family was rich. Each box had partitions to hold the various ingredients like the betel leaf, areca nuts and lime paste. I often watched, KAMPONG SPIRIT – Gotong Royong mesmerised by her long, slender fingers filling the leaf with the ingredients, then folding it into a tight quid and then pushing it into her cheek. When she chewed it, the combination would turn into red juice which she spat out into a small spittoon. Then she would use her red kerchief which she kept on her shoulder for the purpose of wiping her mouth.

“It’s a disgusting habit,” Ah Tetia used to say. “It’s addictive and it will cause mouth cancer. You should give it up.”

“It’s tradition,” she said.

But Mak did give it up eventually. Another part of her former life erased from her memory. But she still loved talking about the mountains, and she described the majesty of the Cameron Highlands and Fraser Hill to me. Both mountain ranges grew up from the spine of the Malay Peninsula and were so high that the air was extremely cool, so the English loved to holiday there.

“In the evenings, the stars dripped downward like sparkly jewels and shone with a brightness usually obscured by city lights.”

Her voice was melodious.

Apparently, up in the mountains, the winds were strong, making it chilly, so people needed to put on jackets and coats, like in the picture books thrown away by the English children from Atas Bukit. Except that it still did not snow at Christmas like in the picture-books, though people did light log-fires to pretend that they were in their home country, so they would toast marshmallows, roast local chestnuts and put Christmas stockings up on the mantelpieces above the fireplaces.

When Mak told me things about her other life, her voice would take on a whimsical tone and her eyes would have a faraway look. Her life of luxury and comfort in Malacca was a sharp contrast to her life here in Kampong Potong Pasir. I had a crazy dream that one day I would help her retrieve the luxury she had known.

“How will you go to Tanah Melayu?” I asked Abu.

It was a legitimate question as not very many people owned cars. Certainly not the majority of our villagers. Those who did, used their cars as a means of earning a living. Many in the village used their cars as ‘pirate taxis’, or pawang chiar in Teochew. Instead of the prescribed four passengers permitted in a car, the pawang chiar could carry as many as eight adults, squeezed against one another like sardines in a tin. This would cut down the cost of the fare for each passenger. Sometimes the pawang chiar was used to ferry children to school and the owner would place a wooden plank across the back seat which would allow him to carry up to twelve children!

“Oh Bapak said we will go by kereta-api,” Abu said.

The literal translation of the Malay words, kereta-api is vehicle-fire. Presumably, the term was coined when a train was powered by coal and had a furnace. Tanjong Pagar Railway Station, located along Keppel Road, was the only railway station on our island. Opened in 1932, the station sat on reclaimed land and its foundation was reinforced with concrete pilings. The British leased the land to the Federated Malay States Railway (FMSR). The three-storey station building had an interesting mix of architectural influences, art deco in some features, neo-classical in others. The main hall had an impressive high ceiling with windows that let in natural light.

“How exciting,” I said. “I would love to go on a train journey.”

“Yes,” said Fatima. “I’m really looking forward to it.”

“Our father said that we will be able to see the new Stadium Merdeka from grandparents’ home,” Abu said with his usual authority. At fourteen, Abu displayed all the attributes of a leader and orator. If circumstances had been different and he had been educated, he would have gone very far in life.

“What’s a stadium?” I asked stupidly.

“It’s a huge place,” Abu gestured, opening wide his arms. “With thousands of seats around a giant space where people can watch football or enjoy a concert. But this is a special stadium. The people of Malaya are building it to celebrate our In-de-pen-dence.”

He used the English word, separating each syllable so that I could grasp the foreign word. My father’s thinking was limited like the men of his time, so he felt that it was a waste of time and money to let girls be educated, therefore I was not permitted to go to school. So I did not know any English. Abu gleaned English words from here and there, which showed he had an agile brain.

Abu rose to his full height and stood tall, like at a political rally.

“Bapak said we’ve been ruled by Orang Puteh, (White People) for too many years. Finally we’re going to rule our country ourselves! On August 31, we will be free to do so. The stadium is called Stadium Merdeka because merdeka means ‘independence’. Freedom.”

Although he spoke his father’s opinions, he said it like he too was thinking of the same thing. Sometimes Abu seemed more adult than his age.

“Come on,” he urged. “Make a fist of your hand and swing it upwards and say, Merdeka! Merdeka! Merdeka!”

What Abu said, the village children did. Fatima and I followed behind him, raising our arms and shouting merdeka! I just thought it was fun to follow him but really didn’t have any idea of the importance or significance of our words. Soon the other kids joined us and then more kids joined us as we snaked our human-train around the yard, chanting in unison and repeating, merdeka! merdeka!

The older kampong folks looked at us amused. My father had just arrived home on his bicycle. He cycled miles each day, all the way to Bukit Timah, where his office was located, and back. He relaxed each evening with a pint of Guinness, talking about politics with Ah Gu.

“Ya, Merdeka,” Encik Salim said. “First Malaya, then maybe Singapore.”

“Well,” Ah Tetia said. “My English boss commented that the Colonial Office in London seemed to regard our new Chief Minister, Mr Lim Yew Hock, with more confidence.”

“Mr David Marshall tried his best to get us internal self-government...”

Politics was men’s talk in the village and since the country’s first Chief Minister David Marshall’s resignation in 1956, conversation had been buzzing.

Ramu, who worked as a peon at the main Post Office at Fullerton chipped in, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Mr Lim Yew Hock’s delegation to London was successful?”

“Yes indeed,” Encik Salim said. “Then we will have a Yang Di-Pertuan Negara as head of state instead of a British governor!” There was a new wave of hope in the country. Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock’s government was making good progress. He came back to Singapore with a new Citizenship Ordinance. For the first time, people born in Singapore were classed as Singapore Citizens and not just as British.

Ah Gu told his friends the news.

“People who are born in Singapore and the Federated States of Malaya can apply for Singapore Citizenship,” he announced. “Also angmohs who have lived here for more than two years...”

Ah Gu was a fund of political information. He loved to keep abreast of all the news and then display his knowledge to the rest of the villagers.

“Well, it will be good to be free of the British,” said Pak Hassan. “But if Malaya gets her independence and we don’t, it means we will be separated from the Federated States. We’ve been a part of them for so long...”

“Indeed,” my father said. “Us Peranakans feel slightly dismayed too. We’ve been called Straits Chinese by other Chinese people because we are part of the Straits Settlements along with Malacca and Penang. If Singapore is cut off, it will be like a separation of conjoined twins. We’ll be divorced from our heritage.”

I had never heard my father speak in such poetic terms before. There was a great deal about my father that I did not know. Perhaps he was expressing the tentative feelings of the ordinary populace. A new era was dawning but it was not all going to be perfect.

“Okay, okay,” Pak Osman said. “It’s marvellous if we get our freedom from the British. But right now, my main concern is freedom from our village tyrant. We are setting the trap tonight and we need all the help we can get, lah.”

Sivalingam was the village goat-herdsman. He lived alone with his kambing. He housed them underneath an attap-thatched roof supported by thick wooden posts, no wall around them, with straw and mud underfoot. During the monsoons, when heavy rain lashed at his humble dwelling and turned his floor to slippery mud, he would create a tarpaulin wall. He himself slept on a cot of rope or charpoy beside his animals. When you ventured near the stalls you could smell the goats’ excrement and urine. Sivalingam was obviously oblivious to the smell. If you should stand close to him though, you would realise that the dank smell of his goats clung to his dhoti and body. He bred the goats for their milk and when the animals became too old to produce milk, he sold them as mutton to the Tekka market beside Rochor Canal in Little India.

Tekka was the largest wet market in the country and was a busy bazaar for fresh meat, poultry, fish, vegetables, fruits and spices. Tek is Hokkien for bamboo and ka means by the feet or clump. As clumps of bamboo grew around that area of Serangoon Road, the market was named after them. They also sold gaudy glass bangles, saris and local crafts. The building itself was magnificent, built in 1915, based loosely on the design of London’s largest market, Covent Garden. All the local farmers brought their produce to Tekka. It was such a fascinating and exotic place that even the angmohs could be seen shopping here, usually with their black-and-white amahs or Malay drivers in tow. Though mutton had a strong aroma, it was particularly delicious in hot curries and dalcha, and a local delicacy called Sup Kambing. Like mutton, goat’s milk had a strong flavour and was considered the poor man’s option to cow’s milk.

“I shall provide one goat as bait,” Sivalingam said, nodding his head in Indian fashion to Pak Osman. “Better to have one less goat than the python raiding my place and killing the whole herd.”

He selected a goat which had recently broken its leg when it stumbled into a pot-hole. The village lanes were full of potholes. The goat was not producing much milk anyway and it seemed merciful to consign it to its afterlife. But still Sivalingam talked to it as if he was talking to his child, patting it, cajoling it. The village folks had often seen him muttering to his goats and thought he had gone funny after living with them for years. His goats were family to him.

That evening, with tears in his eyes, Sivalingam led the hapless goat to the stake erected by the Elders. This was in a spot not far from the grassland but in an open area so that the villagers could see all that transpired whilst waiting in the bushes with their parangs and pitch-forks. A carbide lamp provided the light, the naked flame, hissing and spluttering. Sivalingam reluctantly tied his goat to the stake, and as if the goat knew what was about to happen, it whined and kicked its hooves, making the dust fly.

“Shhh, shh, shhh,” Sivalingam tried to placate it. “I will ask Lord Shiva to take you quickly so there’ll be no pain.”

After saying his farewell, Sivalingam slipped into the bushes with all the others and started a bhakhari japa, chanting Om Namah Shivaya, Om Namah Shivaya for Shiva to assist in the goat’s transition to the afterlife.

“Quiet!” Pak Osman said. “You’ll scare the python off!”

So Sivalingam had to resort to the quietest of the japa, manasik japa. He chanted under his breath. The group waited, shivering a little as the trees and shrubs in the grassland took on spectral shapes as the moon rose. Perhaps the stories about ghosts and the pontianak inhabiting the grassland were true after all. The breeze picked up and brought a waft of fragrance. Everyone’s flesh crawled. It was the scent of the chempaka flowers! The pontianak was a female vampire who always took on the guise of an attractive maiden. Some men longed to gaze at her legendary beauty yet were filled with dread. She was said to live in the banana tree but loved the chempaka flowers whose fragrance was associated with her. She was on everyone’s mind. The men’s imagination took flight and they almost expected her to appear out of the grassland, levitating towards them. They jumped in fright when the tall lallang suddenly parted.

But it was not the pontianak, it was the python.

The men gasped as the snake’s head appeared, then his body. Like a blind person moving along and using his sense of hearing, the snake paused as he tried to register where his victim was located. His head swivelled here and there until it stopped in the direction of the goat, whose fidgeting had attracted him.

“I can’t bear to watch this,” Sivalingam said.

He left the group to go back in the direction of the village. He was glad he did not stay because he heard later that his goat bleated suddenly with fright. Then he heard the sound of his goat’s thrashing hooves. The worst was happening. It broke his heart to send his goat to its demise this way.

“Om Namah Shivaya! Om Namah Shivaya!” He chanted loudly now to quell the sound of his furiously beating heart.

“You should have seen it, the belly of the python swollen with your goat...”

“Spare me!” shouted Sivalingam.

“Samat!” Pak Osman interrupted the man. “How can you be so uncaring? Don’t upset Sivalingam with the details. Just thank him for his sacrifice that has saved the village!”

Samat offered the python steaks to Sivalingam but he would not take them.

That evening, Pak Osman organised a communal charcoal spit. By dinner time, the fire was blazing. It felt like a celebration, hurricane lamps all around to light up the place, people dressed up so the mosquitoes would not feast on their flesh. A young Malay man, Karim, the village’s musical protégé, brought a guitar and started to pluck at its strings. Although uneducated, with the unenviable job of clearing the latrines and outhouses, he could play immeasurably beautiful music that moved people to joy and tears. The musical notes rose into the stillness of the evening and children clapped and danced around the fire. The atmosphere was like a temasya, a Malay word for a cultural evening.

Then the python steaks were brought out. The women had cleaned and prepared the meat which had been skilfully skinned, then marinated in freshly ground spices: ketumba, jintan manis and kunyit. The coriander, cumin and turmeric took away its gamey smell. Without its distinctive skin, the steaks, with a bone in the middle looked like they could be mutton chops or eel chops except that they were in larger chunks. The men grilled the steaks on the hot charcoals wrapped in banana leaves which wilted and browned and brought out a mouth-watering fragrance. Everyone in the village had a fair share.

Fatima and Abu had returned in time to share in the largesse.

“What was the stadium like?” I asked them.

“Oh it was magnificent,” said Abu. “The crowd there was so inspiring. Did you know that the Federated States of Malaya will gain independence from the British on August 31? From then on, our own people will rule our country. We shall be independent. No Orang Puteh to tell us what to do anymore. We will be free! No more tyrants to rule over us!”

“Oi! Budak! Child!” Pak Osman slapped his wrist. “Chuchi mulut dengan sabun! Wash out your mouth with soap! Be careful with your expressions. Some words are better not said. You never know who’s listening.”

“But Pak Osman. Don’t you think that that the Orang Puteh are tyrants? Don’t you want Singapore to be free too?”

“I said Enough! Go and get your sister a piece of python steak.”

Realising from Pak Osman’s tone that he had stepped over the line, Abu quickly apologised, “Ma’af, Pak Osman. I’m sorry, Pak Osman!”

We were in an age when young people still deferred to their elders and showed due respect. Rude words uttered by children were punishable by washing their mouths out with soap, or more serious rudeness warranted the mouth to be stuffed with hot chilli paste, sumbat sambal belachan. I can testify that the latter was a fate worse than being caned with a rotan. I had been a naughty, outspoken girl indeed.

“Ya, ya, ya,” Fatima said impatiently. “I’m hungry.”

Abu rolled up his eyes, but he scuttled off obediently.

“What’s the python steak like?” Fatima asked me, making a face.

“Oh, you don’t have anything to worry about. It’s very aromatic and delicious,” I said. “It tastes just like fresh kampong chicken, lah.”