IN OUR KAMPONG in Potong Pasir, we were not woken up by the harsh groans of mechanical engines or the screeching of wheels on hard tarmac. Nor were we blasted into wakefulness by loud radios. Instead, in our rural bliss, we were treated to the delightful guttural crows of a rooster or the sweet singing of the dawn chorus. Groups of starlings nesting in the tall angsana trees would start twittering, then stretch their wings to fly out and coast along our roofs. The mynah birds with their clawed feet scratched our dry attap, looking for their breakfast of beetle, lizard or centipede. The sounds would rouse us out of our sleep. In the half-light, when the first rooster crowed, it might be echoed by other cocks in the village, their harmonised music as if orchestrated by some divine conductor. It was a gentle kind of awakening, the sounds of nature lightly treading on our semi-consciousness; the sunlight softly streaming through coconut fronds – and holes in our attap roofs.

“When we lose touch with nature, our chi shrivels within us,” my mother used to say. “It’s important to breathe amongst trees and flowers; feel the wind in your hair, the sun on your skin, the sand under your toes, or smell the salt in the air. You should never be too busy to connect with nature.”

Mak had a reservoir of such sayings. She was alive to life.

I could smell coffee being brewed. I loved to awake to its aroma.

It was a Sunday and my father was not working, so he was preparing breakfast, to allow Mak a few more minutes in bed. Another baby, a boy this time, had been born in the previous year, when Mak was forty-two. It was probably her sixteenth pregnancy or somewhere around that number, so she needed rest. She had so many children, she had lost count. She had a child every other year since she was married at seventeen. Conditions were dire; there was little money and nutrition was poor. When my mother shopped at the wet market, she could only afford to buy vegetable cut-offs that were meant for animal feed. Any meat she bought would be gristle or fat to flavour our soups and curries. It was no surprise then that only eight of us survived, and one was given away. There was no system of birth-control, except abstaining. But which woman dared to tell her husband to abstain?

We meant a lot of hard work for Mak, who did everything without complaint – scrubbing and washing our clothes by hand at the well, cooking on kerosene and clay stoves, cleaning with no sophisticated machines to lighten her load, clearing the smelly chamber-pot every morning. Ah Tetia was not the most domesticated of husbands and he could be demanding; and in his tortured moods, he could be violent. At other times, he demonstrated a tenderness that would melt anybody’s heart. Even his features softened. It was at times like this that I understood how my mother could love him, despite his abuse.

“Wake up, Ah Phine,” he said, tickling the soles of my feet. “I’ve got your favourite bak ee today to eat with moey, rice porridge.”

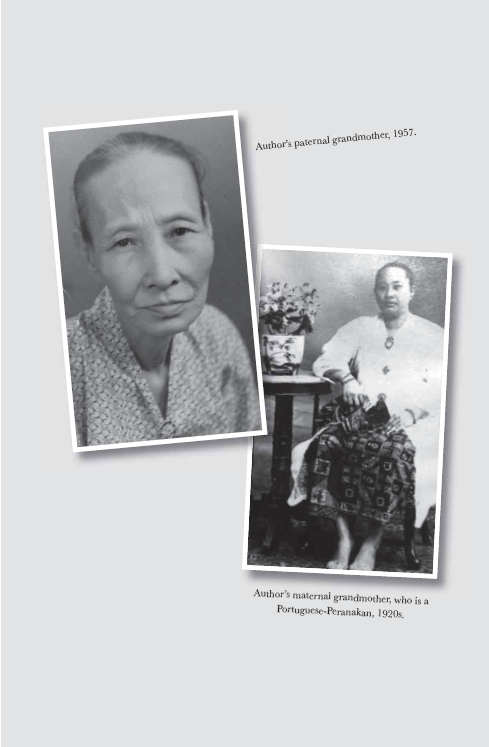

His mother, my Lao Ee, made the most delicious Peranakan minced pork patties, little round rissoles of minced pork with chopped onions and chillies bound together with raw egg, then fried till golden brown. The taste was simply saliva-inducing, KAMPONG SPIRIT – Gotong Royong made all the more exquisite because meat was such a luxury for my family and many other families in the kampong. My father often dropped by at grandmother’s place in Petain Road on his way back from Bukit Timah where he was a Bill Collector in an English firm. Petain Road was just off Serangoon Road so was not out of his way. I always thought of Lao Ee fondly, pictured her in her kebaya panjang, the handkerchief slung over one shoulder. The handkerchief was an old habit from her sireh chewing days, used to dab the saliva from her mouth. Like my mother, she had finally given up the traditional pastime, due to a fear of its cancer-causing propensities, and the unsavoury necessity to spit out red juice into spittoons. Her upper back was beginning to curve, so she looked as if she was constantly stooping. Lately she had adopted a shuffling gait, as if unwilling to walk briskly to her demise. Like all Peranakan women, she was a great cook. I whooped for joy whenever Ah Tetia brought home the patties she made. It was such a treat. Grandmother, who lived with her fourth son and family, was aware that our family did not get as much to eat as my uncle’s family.

Eldest Brother, whom we addressed as Ah Hiah in Teochew, meaning Elder brother, blamed our poverty on my father’s stupidity.

“It’s not as if we were that poor. Father was in charge of rice-rationing in the war so he earned lots of banana-money.” He often told our siblings in frustrated tones.

Banana money was so called because the money distributed by the Japanese conquerors had the picture of a banana tree on its notes.

“Instead of investing the money in buying a house or land, he stored it in chests underneath the bed. He never expected the British to come back. Of course, when they did return, the banana money was completely worthless!”

Arguments between my eldest brother and father often escalated into fisti-cuffs. They were both strong-willed men. In that sort of situation it was hard to see the softer side in them. But nothing is black-and-white, life has a lot of grey.

I watched my father with love for his gentleness. Ah Tetia strained the coffee with a calico-cloth bag, then poured it into an enamel coffee-pot. He stirred condensed-milk into it. By the time breakfast was served, my other siblings and Mak were also up. They took turns to bathe at the well, my eldest brother drawing up the pails of water for Mak. He had just started training to be a teacher at St. Andrew’s school, the Anglican missionary school across the Kallang River from our village, where Francis Thomas used to teach before he became a Member of Parliament. Eldest Brother was an ace student in science and mathematics. If our family circumstances had been different, he could have pursued his dream of being a pilot. Instead he had to be a teacher where his training was funded, and he could start earning quickly to support the rest of us. The responsibility rested heavily on his young shoulders. In his way, he too gave me opportunities I would not have had otherwise. My mother always reminded me that we had to be grateful to those who helped us along in our life.

We sat cross-legged on our crude cement floor in the kitchen as we did not own any tables or chairs. To eat our moey, rice porridge, which was served in china bowls, we used chopsticks and a china spoon. This was similar to how the Chinese ate. But when we had rice, we ate it in a plate rather than a bowl; and we used our fingers to eat, like the Malays. Our Peranakan culture was a rich mix of Malay and Chinese customs and cultures. Who decided what we selected from each was a mystery to me. Ah Tetia was in his usual home attire, a checked sarong, his chest bare. He was in his late forties and was already losing his hair, but his body was rippling with muscles.

“Do you want to join me in weight-training later?” He said to two of my elder brothers light-heartedly. “Both of you look too scrawny.”

Outside in the sandy yard, Ah Tetia had set up the home-built weight-lifting gym, a rough-hewn wooden bench, bar-bells hoisted across sturdy posts. Weight-lifting was his and Second Elder Brother’s Sunday recreation. But he also had to keep fit because he had to cycle daily from Potong Pasir to Bukit Timah and back, which was a mean feat considering the distance. My father and brother were sometimes joined in his weight-lifting session by two younger men from the kampong, Rajah and Salleh, both of whom addressed my father as Inche or Mr Chia. My father had a kind of status in the village because he spoke some English, which was rare among us.

Our Indian neighbour, Krishnan, also spoke some English, as he worked for the City Council, though people still referred to the government body as the ‘Municipal’. It was a government department dealing with roads, water and electricity, and had changed names in 1951. Krishnan stayed aloof, as he was a Brahmin, the priestly Indian caste, and he felt he was too highbrow to socialise with the villagers. He did not even participate in the capturing of the python which had plagued the village the year before, nor joined in the barbecue afterwards. But his wife and two daughters, Devi and Lalita, did not put on any airs. I was friends with both girls, who were older than me, and like me, were uneducated. Kampong children did not have either the privilege or luxury to be educated as a matter of course, especially if they were girls. I had longed to go to school but my father had refused to let me.

“Your mother really makes such good bak ee,” Mak said, biting into one.

My father smiled. He was really handsome when he smiled. Then, picking up one more rissole with his chopsticks, he placed it in Mak’s bowl. This gesture was the height of Asian caring, and in subtler ways it was a kind of courtship ritual. A Peranakan couple on their wedding evening had to feed each other with morsels of food left out for them in the bridal chamber, before they could consummate their marriage on their elaborately decorated wedding bed. The ritual was symbolic of their nurturing each other. I hoped Ah Tetia was not getting amorous again! I did not think that Mak could survive another pregnancy.

“Eat! Eat!” Ah Tetia said.

After the breakfast things had been cleared, my father said to Mak, “Well, are you going to tell her or shall I?”

“You tell her since you’ve decided...”

My mother was a typical Asian woman of her time, deferring to her husband’s opinion and decisions. And even if it was she who had decided, she would not let it be known publicly so that he could save face. She never argued outright. It was drummed into her that a man’s ego was fragile and needed constant boosting. She was taught that he would be more agreeable when he felt himself to be lord and master in his home. It did not always work, as my father sometimes demonstrated, when his demons entered him. But still, on the whole, Peranakan girls were nurtured by their mothers and grandmothers to practise this delicate balance of appeasing their husbands, yet getting their own way. Although many Peranakan girls were not educated formally, their home education was intense. They had to learn how to cook, how to keep house and manage servants if they were wealthy; how to sew and embroider, how to play music and sing keronchong – and how to pleasure their husbands.

I was horrified. What were my parents going to tell me?

Maybe they were thinking of giving me away too. My heart skipped several beats at this possibility. Although it had not been discussed openly, I had understood from my brothers that one child had been given away just after the Japanese war, when Ah Tetia did not have a job. This was not unusual in rural areas; not everyone registered a birth promptly. But how it must have grieved my mother. It was the test of a mother’s strength to give a child away so that he would have a better life than to keep him with her to suffer their poverty. If a boy could be given away, what lay in store for a girl like me? Ah Tetia had spelled out so many times that rice rations were wasted on girls, as we would belong to our husband’s household after marriage. That was why he did not bother to educate me. He had also said, “Education poisons a woman’s mind.”

Though we did not have much, and life in the kampong was challenging, I did not want to be given away. I loved my mother and my family. I did not want to be separated from them. I was told that once before, when I had been six months old, my father did want to give me away. A Sikh neighbour who was childless had asked to adopt me. My father tried to persuade my mother that I should be given away. But my mother had said No very vehemently. Had she changed her mind now? Fear clutched at my heart and made it beat like a trapped bird in my chest.

“I’ve agreed to allow you to go to school. Provided that you help your mother to sell the nonya kuih to pay for it. No money is to be taken out of the household expenses. Understand? Maybe a bit of education will get you a job and you can look after us in our old age...”

I could not believe what I was hearing. First, I was relieved that my parents did not intend to give me away. Secondly, it was a dream come true to go to school! My mother and father had come to blows, literally, on the subject previously. I was already seven and children my age had started school the year before. It was a prospect beyond my wildest imagination. Of course my mother must have used her pillow talk to accomplish this feat. The latter was a term to describe the period when couples were in bed and chatting intimately. Usually the husband would want to exercise his conjugal rights at such times, and was willing to be more pliable and sympathetic, thus giving his woman the opportunity to ask for things he would otherwise refuse.

“Speechless, are you? What good is school going to do for you if you can’t speak out?” Ah Tetia teased. “School has already started but if your mother can find a school which will take you, you can go.”

Just at that moment, Rajah and Salleh turned up.

“Hey Mr Chia. Ready to carry weights or not?”

“Of course! Of course! We can all pretend we are going to compete in the British Empire Games like Mr Tan Howe Liang.”

Like Second Elder brother, Rajah and Salleh had young, well-sculpted torsos. They were tall. With their dark brown bodies, they looked like heroes who had strayed from a Shaw Brothers film-set. The young men assisted my father and brother to set up the weights, chatting excitedly about the possibility of Tan Howe Liang bringing home a medal from The Games. Singapore’s favourite sportsman and weightlifter had been born in Swatow, China and had immigrated to Singapore after the Japanese war. He had participated in the Olympic Games in Melbourne two years ago in 1956 but had not won anything. This year he was going to Cardiff, Wales, in the United Kingdom, to make another attempt. The British Empire Games were held every four years. They had been started in 1930 by a Canadian, Bobby Robinson, in Hamilton, Ontario as a way to bring the disparate peoples of the British Empire together in friendly sporting competition.

“Sure got chance one, this time,” Salleh said with enthusiasm. “He’s so determined and has trained so hard...”

“He’s definitely going for gold...” Rajah said.

I was going for gold too in a different way. I was going to school! It was so precious I could hardly believe it was coming true.

My mother, who had no education and no ability to read English signs, asked many schools to take me in mid-term. She was refused by several convent schools. Eventually she met a kind principal of a Government School, who admitted me for the second term of the academic year. She was Miss De Souza of Cedar Girls Primary School, whom I considered to be my first guardian angel, for giving me a start to a new life.)

Cedar School was beyond the scenic Alkaff Gardens in Sennett Estate, a smart housing development across the road from our village. Upper Serangoon Road, a tarmac road compared to the sandy one in our village, divided us like a boundary between the poor and rich; our village was a shantytown of wooden huts with attap roofs, whilst the houses in Sennett Estate were made of bricks and concrete and had flush toilets and electricity. The disparity was great.

“We have to go to Bras Basah Road to buy books for you,” Mak said.

Two years previously, my father had taken my mother and me out for our joint birthday treat in town, since my mother and I shared the same month for our birthdays. I remembered the name Bras Basah Road because Ah Tetia had told me the story of how it had got its name. (See Chapter on Clarion Call of Hope). The words were supposedly a corruption of the Malay words, beras basah, wet rice. Beras was uncooked rice grains. As rice was a staple food in the region, the indigenous Malays had several words for rice; padi meaning rice on stalks in the field, nasi meaning cooked rice, nasi bubur meaning rice cooked into a gruel.

The wooden shophouses along Bras Basah road were a contrast to the concrete magnificence of the curved white facade of St. Joseph’s Institution. It was a Catholic school for boys and it looked rather posh. The school faced the sprawling grounds of The Good Shepherd, the largest Roman Catholic cathedral in Singapore. The cathedral had a splendid spire and was a beautiful building styled after one of the churches in London, the Church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. It was hard to picture The Good Shepherd in its original state in 1832 when it had been made of wood and had an attap roof, like our kampong houses.

On the way to town, the skies had opened up and now the rain was lashing us from all sides as we disembarked from the Singapore Traction Company (STC) bus. Luckily my mother had the foresight to bring an umbrella, and we hugged closely underneath the waxed-paper umbrella with its wooden spokes, as we dashed to the five-foot-way for respite. Some people credited modern Singapore’s British founder, Sir Stamford Raffles, with the idea of creating these open corridors under the first floor of a building to shield people from the tropical sun and the onslaught of heavy rain. Others credited Alexander Laurie Johnston for its design. He had been a prominent merchant who came to Singapore in 1852. Whoever gave birth to the concept, he was ingenious. All newly erected buildings had to provide this mode of shelter. As the width of these passage-ways was approximately five feet, they came to be called five-foot-way, and this came to characterise the architecture of shophouses.

“Oh, the rain is so heavy!” my mother said. “I hope your father and brothers remember to put out the pails and tins to catch the leaks.”

When first weaved for our kampong roofs, attap was fresh, newly dried palm fronds. But continual exposure to the hot sun made them dry and brittle. Designed so that the breeze could lift them and let air into the houses to cool them, this very action sometimes caused damage to already brittle leaves. The birds foraged for food too, breaking the dry attap with their weight. As our houses did not have any ceiling, the holes would let the rain fall directly into the houses. As soon as thunder clapped, there was the usual scuttling to collect pails or kerosene tins to put under the gaps in the attap. This was what Mak was referring to.

“Don’t have much money so must buy second-hand books,” Mak said.

“It’s okay, Mak. I don’t mind. I don’t mind,” I said, trying to reassure her.

It was already a miracle to be going to school. I was prepared to put up with the small inconvenience of hand-me-down books which may be somewhat dog-eared, or have doodles and notes squiggled in the margins of their pages, or sentences underlined. Never had I been so filled with utter joy as on that first day of buying books. The shops, manned mostly by Indians, were an Aladdin’s Cave of stationery and magazines; books piled everywhere, on tables and shelves and on the floor. Huge stacks of books towered over me and their smell was so intoxicating; especially the new books which had such a pristine and woody scent. When no one was looking, I fanned the pages of a new book in my face. Its scent became an addiction I never could be weaned from. I was a child, mesmerised, fingering all the different titles and front covers. Some of the books were so old that their pages were yellowed and curled. Pressed amongst some ancient pages were tiny silver-fish, dried and loose. Yet the books had not lost their beauty or allure for me, for within them were worlds I had not fathomed, people I had not met, places I had not been to. My mother was armed with a book-list from the principal that she could not read. Yet she wanted me to be able to read; persevered so that I could read. It was one of her greatest gifts to me.

“I want you to have a life I could not have,” she said.

I am eternally indebted.

Ah Gu, my father’s buddy, with whom he discussed politics, barged into our house unannounced when we were sitting in the kitchen having our dinner. His parents must have been perceptive to name him after a cow, or in his case, a bull.

“We’ve got it!” He said. “Lim Yew Hock’s delegation to London has been successful. We are getting self-government. I heard it on the news on Rediffusion!”

“Do you want something to eat?” my father said, with typical Asian politeness but at the same time knowing that another addition to dinner would strain our meagre resources. “So Harold Macmillan had fulfilled his promise.”

The British Prime Minister had stopped over in Singapore earlier in the year and when questioned on the subject of self-government, he had said, “We will not go back on our word.”

“No need. No need. I’ve eaten.”

My father smiled with relief and offered him an F&N Orange drink.

“Yes,” Ah Gu said. “This is a start. The British will still have control over foreign affairs and defence, but at least we can run our own country. Not quite independence, but not far from it. We will become the State of Singapore and no longer a colony.”

“Looks like our whole country is going for gold...” Ah Tetia said, using the sporting metaphor.

There was a renewed air of anticipation in the country. Suddenly there was hope for a different future, one where we were ruled by our own people. Hope was a jewel for the spirit. Without hope, people would give up. In an individual way, weightlifter Tan Howe Liang too had lived in hope. He was prepared to work hard at his sport and was unafraid to dream. Someone once said, “Without dreams, life is a winged bird that cannot fly.” The country was in suspense during the period of the British Empire Games and it rejoiced when Tan Howe Liang finally fulfilled his dream. He came home from the Games with a Gold Medal – the first for Singapore. But he was not ready to rest on his laurels. He was not finished. He was planning to participate in the Olympics in 1960. Singapore too was not finished – it was striving for its own identity and going for gold in its nationhood.