D.H. LAWRENCE’S INFAMOUS book, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was banned in England but managed to slip the net and found its way into Singapore. Published by Penguin, the novel was derided for its explicit depiction of the relationship between the lady of the manor and a gamekeeper. Perhaps it was the novel’s audacity to suggest a transgression of the British class system that offended? The burning question was, was the book as racy as was suggested? Readers in Singapore wanted to find out. After all, forbidden fruits were said to taste better. Fuelled by the fact that it was a banned book, locals flocked to Bras Basah Road, bookshop haven, to buy the book, which cost only a dollar seventy-five. The bookshops sold five hundred copies in two weeks. People read the book with its covers clad in brown paper.

My father would kill me if he knew that at ten, I was reading romantic novels! To be more precise, Parvathi chose the novels and I read them to her. Half the time, I did not understand the subtle nuances. I simply read the English words. It was my first realisation – one might have the capacity to read but not the capacity to comprehend.

The books we read furtively were not even remotely close to Lady Chatterley! They were rather tame. Their covers often displayed a Western man and woman staring into each other’s eyes. So I did what all my classmates did, which was to wrap the covers in brown paper. There were romances of doctors and nurses, highwaymen and ladies, and blockbusters by Barbara Cartland and Denise Robbins. Innocent stuff actually – no graphic description was given when there was a mention of a kiss. If anything more than the touch of hands was alluded to, the line would go ************. Or as we mimicked: asterisk, asterisk, asterisk. You had to read in-between the asterisks and use your imagination. Sometimes this was much more wild than what the author might have intended!

“If only there was someone who could take me away from my fate,” Parvathi said in earnest. “Then I won’t have to marry that pock-marked old man my father wants me to marry! Do you know that the man is twenty years older than me?”

My Indian friend was fourteen. She still could not read as she had never been to school. Going to school was a luxury and privilege many village children did not have. The romance books were her only escape from a life of work, drudgery and squalor.

“Your father is crazy! You can’t marry an old man...”

“Some of us have no choice...,” Parvathi sighed.

Karim, our village singer and musician started sporting a new hair-style. He used to work as a night-soil man, clearing the buckets from the out-houses, but he was now a fully-fledged musician. In 1959, he had performed at Aneka Ragam Rakyat, People’s Cultural Event, which was a huge celebration held at the Botanic Gardens to commemorate the inauguration of our new government. There he was ‘discovered’, and was offered a full-time job as singer and guitar player in the Great World cabaret on River Valley Road. Now his dark hair was thick with Brylcreem and his forelock was swept down over his forehead.

“What happened to your Tony Curtis curl?” My Second Elder Brother asked.

“Aiyyah! That’s out of date, now it’s all Elvis Presley-lah. Are you lonesome tonight? Do you miss me tonight,” he crooned à la Elvis.

The American singer was said to gyrate with his hips and was considered obscene by some. Compared to him, people found the British singer, Cliff Richards, more acceptable, as he looked more like the boy-next-door. However, Elvis’ voice was creamy and seductive, so his songs were still a big hit on Rediffusion.

Eldest brother had used part of his teacher’s salary to have the cable radio installed in our house. It was our village’s first step into modernity.

Next to books, listening to the Rediffusion was the second great delight. It opened up other new worlds to us. We heard what was taking place around the country through the news, enjoyed listening to the disembodied voices coming into our home bringing in all sorts of information, all sort of music. Elvis, Cliff Richards, Frank Sinatra and local singers like my idol, P. Ramlee, Anneke Gronlo and Susan Lim entered our homes to entertain us. But not everyone in the kampong could afford a Rediffusion, so many of the kampong neighbours came to sit in our house when the news came on. Our house became like a community centre. Then for the first time, we heard the voice of Tunku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minster of Malaya, who urged Singapore to merge with Malaya to become one big nation.

“...We have to make Malaya our one and only home.”

“He means that he does not want Singapore to identify with the Chinese communists,” Ah Gu, who was also listening, elaborated profoundly. “He is cautioning us. With more Chinese than Malays amongst us, he’s afraid we might become a Little China.”

Ah Gu, if you recall, was my father’s friend, who popped by on a daily basis to discuss politics with him.

“The idea makes sense,” Krishnan our Indian next door neighbour, said. He rarely joined in the kampong activities, but the Rediffusion had attracted him, and like my father, he was one of the rare educated men in the village. “Singapore was part of the Straits Settlements and part of Malaya as far back as we can remember. Yet the British gave them independence in 1957 and not us, so suddenly we were left out. Merger with Malaya would make us part of the same whole again.”

“True, true,” Pak Osman said. “I felt like a limb was cut off when we separated from the Federated Malay States...”

“We’re so close geographically, it does not make any sense for us to be separate nations...” My father said.

Our own Prime Minster came on air, “...the solution to Singapore’s future lay in a Common Market and merger with the Federation...”

We liked Mr Lee Kuan Yew as he had personally visited our village during the elections, and we felt as if he was our own hero. We were convinced that he truly wanted to improve our lives – and he had done so, first the filling up of pot-holes in our village road, and then the Mobile Library, which brought us books.

The topic of the merger was hotly discussed amongst the menfolk.

My mother and the other womenfolk provided them with snacks like apok-apok, our Peranakan kueh dada and the bandung drink made out of Rose Syrup and evaporated Carnation milk whilst they themselves clustered in the kitchen, sitting on the hard concrete floor, to talk about the price of food, the difficulty of bringing up water from the well during the drought, and naughty children.

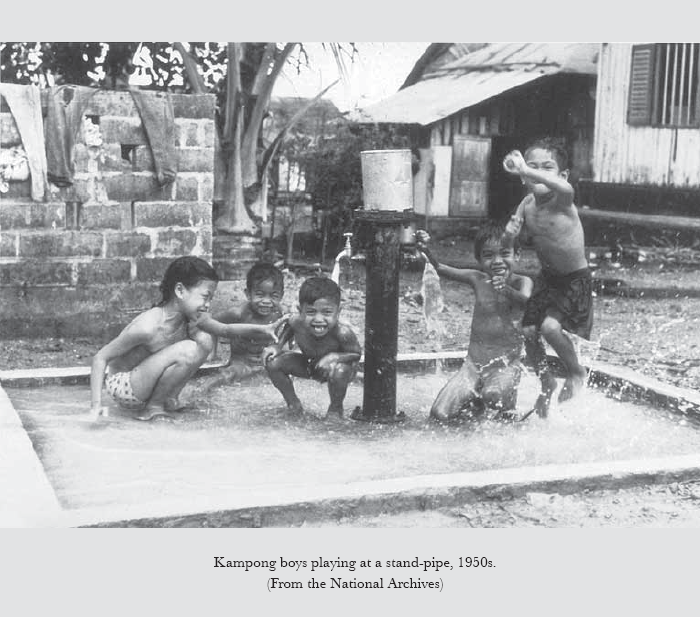

The burning question was – do we or do we not merge with the Federation of Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak to become an integrated nation? But this issue was not the only hot topic of discussion. The weather was too. It had been a very, very hot March, stretching into a sultry April. The white sun bore down relentlessly. Clothes hung on lines dried quickly, the home-starched bed-sheets became stiff like paper, and the attap on the roofs became dry and crusty. We had only one well which served the entire village, and this too was fast drying up. The catfish kept at the bottom to eat up the mosquitoes became so thirsty and lacking in oxygen that they died and floated belly-up on the muddy bit of water that was left. The stand-pipe was at least a quarter of a mile away and its water was regulated so that it was used only for drinking water. But the reservoirs were drying up too, so the water that ran came out of the pipe was slowly reduced to a brown trickle.

We prayed for rain.

Normally the frogs in the ponds would croak and croak and the villagers believed that they were calling for rain. But now, even the frogs were sullen and silent. Even Nenek Boyan, who was supposed to have descended from the tribal batak people and was reputed to practise witchcraft could not persuade them to croak. So she suggested a different solution.

“Thread some whole chillies and onions through a stick and place them outside your front doors and it will bring rain.” She advised.

So, speared into the sandy threshold outside every front door of the village was a kebab of fresh chillies and onions. Still the rain did not come. The village bomoh, the medicine man, danced and waved his arms at the clouds and chanted. But the rain still did not come.

The previous year, we were plagued by floods and now in contrast, we were suffering from drought, our rural lives governed by the capriciousness of the tropical weather. The padi or rice fields, which were usually flooded for the first seeding, were dry, their mud bunds cracking with dryness. The kampong’s four ponds shrank, leaving an edge of exposed bed where some fish could be seen floundering and flipping themselves in a frenzy of thirst. People became listless from the heat, leaves and flowers sagged with exhaustion. More people slept outdoors, on roped charpoys, folded canvas camp-beds and woven straw mats.

I wondered how the English people at Atas Bukit were coping with the heat. The scorching sun must scorch their fair skin and blind their pale blue eyes. Their delicate constitution was not made for our harsh heat.

The attap-roof, woven from palm leaves, exposed day-in, day-out to the blistering sun, became drier and more brittle. All it took was the weight of a small starling walking across it, and the attap would cave in and break, creating more holes in the roof. The attap was quickly becoming a safety hazard, poised for becoming potential kindling. A broken piece of glass caught in the folds of the attap could attract a ray of sunlight and burst into flames. The attap-roof and the wooden walls which our houses were made of were easy to burn. As kampong houses were sandwiched tightly side by side, a single spark could spread like wild fire in dry grass.

One night one of our neighbours, two doors away from our house, was smoking when he fell asleep. The lighted cigarette butt fell onto his pillow and started a fire. His attap-roof rapidly went up in flames. My parents woke us sleepy children and ushered us out of the house hastily. The small passageways or lorongs between the houses made it doubly dangerous as they became packed with people trying to run away from the fire. Luckily the fire was contained very quickly. When the drought persisted, villagers ground their cigarette butts and matches into the sand; and practised extra care to extinguish coals in stoves, candles and oil or kerosene lamps. In heat waves, the normal precaution was to douse the attap roofs with water, but we were rapidly running out of water. What made it worse was that we were running out of fresh water to drink. Our throats were parched.

The government had to intervene.

“The water truck is here! The water truck is here!” A child shouted with glee.

Like a gargantuan messiah, the Municipal Water Truck trundled down our sandy village road. It was greeted with greater joy and relief than the Mobile Library. It was a monster of a truck in size, huge with hundreds of gallons of water, the flexible hose behind it like the trunk of an elephant. We placed our pails and empty kerosene tin-buckets in line to be filled. The driver rationed the water. Each household was permitted only two buckets of water. Second Brother carried our share of the precious water home carefully and proceeded to store it in our giant, Aladdin-type of earthen jar called a tempayan. Each night before we turned in to go to bed, my mother would place empty pails and buckets outside the house in case it rained so that we had water for our washing and cleaning.

“Mari kita mandi dalam kolam! Come let us bathe in the pond!” Abu suggested.

Abu was the elder brother of my close friend, Fatima, and he seemed to have a commanding air about him. If he had been educated, he would probably be successful.

Normally our parents would not permit us to bathe in the ponds. Firstly because the muddy pond-bed was dangerous as it could suck us in. And secondly, it was not exactly hygienic, since the people who lived on the edge of the ponds had their latrines positioned over the pond and they would defecate directly into the pond. One of the village children’s past-time was to go and watch when someone was doing a big job just so that we could see the fish appearing suddenly. As someone pooped and the waste matter plopped into the water, shoals of fish rushed up from nowhere to stir the murky water to feed on it.

“No thanks,” I said. “I will wait for rain.”

Still the rain did not come. By May, we were so hot that we slept with our doors open wide to channel in any little breeze. Of course that let some stray dogs into the house, like the one who was slobbering all over me whilst I was dreaming of P.Ramlee. The worst thing was the rats which came in from the smelly drains and fields.

“The government is negotiating with Malaya to buy more water from Johor,” the newsreader announced on Rediffusion.

As a small island with no fresh water rivers to speak of and only four main reservoirs to supply the country, we were in the unenviable position of having to buy our fresh water from Malaya. Malaya was our hinterland and the Peninsula, with its spectacular mountain ranges and natural fresh rivers and waterfalls, stretched all the way north to Thailand. When we were part of the Federated States, it did not pose any issue to share the water as we were all the same nation. But now that we were not of the same nation, it became more of a concern. So perhaps merger with Malaya would be wise.

On Thursday, May 25, President John F. Kennedy of the United States announced in front of Congress his plan to put a man on the moon. It was a hugely ambitious dream. We could not even fathom such an idea. What would they use to go to the moon? A very special aeroplane? Having a Rediffusion set in our house meant we learnt about things we would never have known about otherwise. Modern technology had brought the rest of the world closer to us.

On the same day, in our village, where the residents were mainly Malay, we were celebrating Hari Raya Haji. This was not a huge affair like Hari Raya Puasa which commemorated the end of the fasting month of Ramadan, but instead this was mainly confined to those who had completed the Haj, a religious pilgrimage to Mecca. People like Pak Osman who had done the pilgrimage wore a songkok or white cap on their head, to denote that they were hajis. On this special day, they had to make a trip to the mosque. After that, they would celebrate by sharing food with neighbours. In our kampong, each of the different races made a point of sharing food with the other neighbours on their new year. I absolutely loved the custom as it meant there was food to eat.

Pak Osman’s wife made the most delicious ketupat, rice cakes made from boiling rice in coconut-leaf bags for hours. These were cut into cubes and eaten with her superbly mouth-watering mutton curry and selondeng or fresh grated coconut fried in aromatic spices. The juices in my mouth ran whilst waiting for the food to be delivered into our home.

It was in the afternoon, whilst we were in this joyous mood, that we heard the terrible news that came over Rediffusion. An attap-kampong, similar to ours, located on the Bukit Ho Swee hillside in the central part of our island, had caught fire. The village was not far from River Valley, where Karim was rehearsing for his performance that evening. We knew from our own kampong that their village would be tightly packed like ours, so a fire in this scorching heat would mean that their attap-roofs were very dry, so they would act like kindle, and the fire would spread very quickly. The other reason for its spread is that, like our kampong, there was probably no running piped water in the houses at Bukit Ho Swee. Like us, they had to rely on wells and a standpipe that was some distance away. So it would be a huge task to put out the fire easily. We could easily imagine how terrified the villagers must be.

We curtailed our celebrations and huddled around the Rediffusion to wait for more news. We became more worried when the reporter said that a strong wind was picking up in that part of the island, fanning the flames as they crackled across rooftops and wooden walls. Before long, we did not even have to sit by the Rediffusion to understand the extent of the fire, because outside, huge clouds of black smoke were billowing into the air. We could smell burning rubber. The fire had spread to a rubber factory where sheets of latex waited to be processed. The stench of burning latex was horrid.

Throughout the day, the fire burned and spread. There was a stark band of bright sunlight above the tree-tops, but beyond that the sky was dark as the winds took the smoke up higher.

Karim came home to tell us how he witnessed the raging conflagration.

“It’s horrible! Horrible! There were minor explosions. I think when the fire got to the oil mills and motorcar workshops. When it ate up the timber-yard, the flames grew brighter and became huge, red and orange. The fire engines were screaming their way to the kampong, followed by the police and ambulance. It was chaos. I don’t know how the people are going to run away...”

We had experienced a kampong fire before, and though ours was small, we knew what it would be like, people trying to escape via the narrow lorongs in panic, bumping, squashing and falling over each other. We knew that the kampong at Bukit Ho Swee was much larger than ours and had well over two thousand attap-houses, jammed tightly together, each wooden wall and attap-roof feeding the fire’s voracious appetite. Our hearts were filled with sorrow. We could only listen to the Rediffusion and watch the sky darkening deeply, and pray that the people, especially the children, had time to run.

Next day the female announcer’s voice was sombre, almost trembling as she reported the aftermath, “Four people died in the Bukit Ho Swee fire yesterday and eighty-five have been injured. Sixteen thousand people have been made homeless...”

Considering the circumstances, it was astonishing that more people had not died. Thank goodness. But sixteen thousand homeless! It was a tragedy on a huge scale! It was our country’s worst kampong fire. It decimated the whole village and relegated it to the annals of history.

The government had the huge task of finding housing for all the homeless people. It was one of the PAP’s biggest challenges. Although the smoke eventually disappeared and the smell in the country returned to normal, there was a dark pall hanging over the nation. But other compelling issues surfaced for the PAP. The bid for merger had caused dissension. Certain people expressed dissatisfaction with the government, making allegations of victimisation and unfairness. The previous year, the Minster of National Development Mr Ong Eng Guan had formed a break-away political party, the United People’s Party. Then Dr Lee Siew Choh formed the Barisan Socialis (Socialist Front) Party.

But it was not all doom and gloom.

1961 was the year when significant changes to the law made life more tolerable for women. The Women’s Charter was brought in, making it illegal for girls under sixteen to have sex or to be married off. This spared Parvathi temporarily from being married to the pock-marked older man. Men were not permitted to marry many wives and were now financially responsible for their first wife and children. There was more protection for women and children against abuse, especially physical abuse. But though this was made legal, it was still not easy to implement, as women like Parvathi’s mother or my own mother would not have the wherewithal to report such cases.

Though those of us living in the kampong would never dream of aspiring to go to University, we cheered when we heard the news that a woman, Professor Dr Winifred Danaraj was appointed Chair of Social Medicine at the University. She had graduated from King Edward VII College of Medicine, which was established in 1905 as the Straits and Federated Malay States Government Medical School. She was awarded a Fellowship in 1950 and was also a Queen’s Fellow. She had also been a Postgraduate of Harvard School and London University of Public Health. First Mrs Hedwig Anuar, who became in charge of our National Library, and now, Dr Winifred Danaraj. They were our trail-blazers.

It gave us other women a chance to dream. We had not dared to hope before, especially those of us who were brought up in poverty and in the villages, under strict rules made by our fathers, uncles and brothers. Now it looked as if there was a small window opening, a window that was allowing light to pass through so that women did not have to remain subjugated by men. It was a significant moment for young women like us. Maybe life could be different for young girls like Parvathi. All was not lost.

For the first time in our lives, we felt that we could really aspire to be what we wanted to be.