MALAYA’S PRIME MINISTER Tunku Abdul Rahman and our own Lee Kuan Yew had a shared vision of a united Malaya and Singapore. Before Malaya became independent in 1957, the Federated States of Malaya and Singapore were considered Malayan. These two visionaries saw that it would be advantageous to be one again. They were men who dared to dream. But sadly, there were many others who tried to thwart their dreams.

It should have been a year of joyous anticipation and rejoicing.

After all, since 1959, when we attained self-government, we had looked forward to the time when we would have full independence. This was finally going to happen on August 31, 1963. Britain had agreed to hand over the sovereignty of Singapore and North Borneo to the new Malaysian government. But there were blots on the political landscape. The Barisan Sosialis Party of Singapore had already made apparent its disapproval of the merger. Now our neighbouring countries of Indonesia and Philippines also spoke out against it. The Philippines had revived an old claim to British North Borneo, whilst President Sukarno of Indonesia desired Malaya and Borneo as part of his own territory. As early as January, after one of his aides returned from a meeting in Beijing with Chairman Mao, President Sukarno said that the formation of Malaysia was not acceptable and he would react with konfrontasi, the Indonesian word for confrontation. He sent troops to North Borneo and even into Malaya. Disturbances erupted here and there.

British troops had to step in to provide assistance.

Those who dared to dream pushed on – their dreams were a bright beacon of light in the darkness that enveloped us.

I too harboured a dream. It was a preposterous dream.

I dreamt of being a writer – in English.

Ever since I had encountered the English language, I was filled with a kind of joy that was indescribable. I loved its cadence, its music, its depth and subtlety of meaning. I loved the Janet and John books, Enid Blyton’s famous books, and every storybook I could get hold of. I even enjoyed the romantic novels that Parvathi made me read to her. I loved the pleasure of forming English words to create stories. I was fluent and literate in Malay and could write essays and compositions, but it did not spark me to want to write books, as the English language did. So I started by writing a comic.

Parvathi brought me scraps of paper from the factory she worked in. I cut them into three-inch rectangles. I wrote a story in simple English for the village children and illustrated it myself with pencil drawings. I stapled the pages together and sold each for five cents. These were my first earnings as a writer!! Actually the five cents included my reading it out as well – if the child could not read!

“Hey, Phine! Your stories are good,” the kids said. “Maybe you should be a real writer.”

But I did not dare to share my dream with anyone. It would sound ridiculous. I was going on twelve. How could I know what I wanted to be? But I did know. Perhaps I had a prescience about my future.

1963 was a special year for me in the Chinese lunar calendar because on January 25 of the Gregorian calendar, the Lunar New Year that began would be a Rabbit Year. I was born in a Rabbit Year in 1951. Each new Chinese year coincides with the advent of spring in China so it is also called the Spring Festival. The night of the first day of the New Year has the new moon, though invisible, and the celebrations end on the night of the full moon, on the fifteenth day. The lunar calendar years are named after the twelve animals of the Chinese Zodiac. Folklore said that The Creator called the animals to him, and he named each year in the order they arrived: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig. This meant that one’s animal birth year would only come round every twelfth year. If you reached the age of sixty, you would be in your Golden Year, which would be your fifth twelve-year cycle.

Each animal sign has its own characteristics, which are governed by its element which, in turn, has its own propensities. The Chinese birth signs relate to five elements: earth, metal, water, wood and fire. This meant that when you reached your Golden Year, you would enter the same element which you were born under. The year 1963 had the element of water. Mine was metal. Experts in the Chinese art of geomancy, feng shui, made their predictions based on one’s animal sign, element, hour of birth and the Kua or Auspicious Direction.

We Peranakans celebrated Chinese New Year. Our culture was a mix of the Chinese and Malay. Most Peranakans started off as Buddhists or Taoists. I loved Chinese New Year, as it meant we got delicious food to eat, as well as new clothes. Peranakans, like many Chinese, were very pantang or superstitious. So they bent over backwards to fulfil every Chinese New Year obligation. Preparations for the New Year started weeks before the event. There were kuih-kuih or Nonya cakes to be made, new clothes to be sewn, furnishings to be changed, the house to be whitewashed with kapor or lime-stone, and the cement floor to be scrubbed. It was a labour-intensive period, and everything had to be done manually.

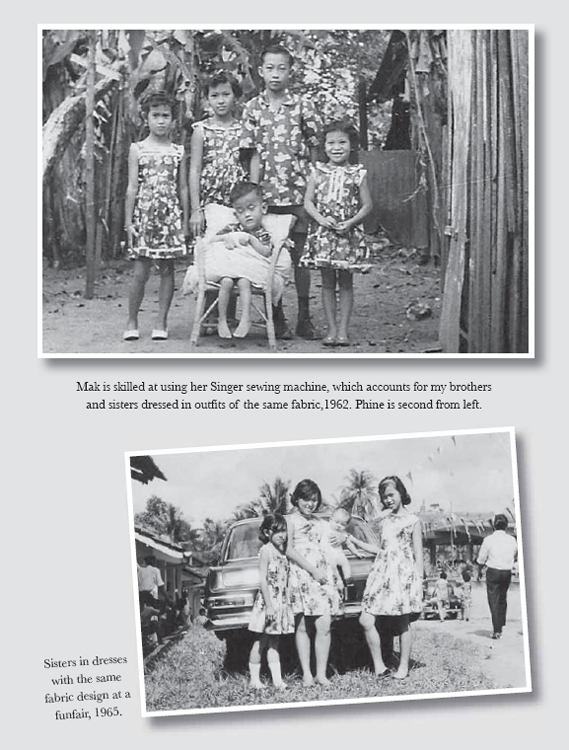

My mother peddled furiously on her Singer sewing machine to make new clothes for my siblings and myself. As usual, she managed to find a bolt of fabric from Robinson’s Petang, or the Thieves’ Market. From experience, my brothers and sisters knew we would end up with matching dresses and shirts! My brothers were none too pleased when the fabric was floral. In bad years, when she could not buy enough fabric to sew curtains for the house as well as our clothes, she would hang up new curtains but use the previous year’s curtains to make into clothes – so the clothes could still be regarded as new. It was imperative for each person to wear a new article of clothing on the first day of the Chinese New Year, to bring in good luck. Of course, black was a taboo colour as it was used for mourning. Although Mak made Western-style clothes for us, she herself wore only the sarong-kebaya.

“You father has given me some money to make a new kebaya for New Year,” my mother told me happily. “Come on. You can come with me to Joo Chiat to choose the material.”

Joo Chiat was in the Eastern sector of our island and was considered a part of the seaside village of Katong, the rich Peranakan enclave. Many Eurasians also lived in the vicinity because of its close proximity to the sea and its luxury houses. The road and area of Joo Chiat was named after Chew Joo Chiat, a nineteenth Century Chinese trader who had married a Peranakan girl. With great foresight, he had bought huge tracts of land to grow gambier and coconut trees, which were highly valuable. These made him into a multi-millionaire. To cope with any possible threat of war, the British wanted to build a road that would run from the city to Changi, where they planned to build their sea defences. The road that ran through Chew’s plantations was a dirt road. As military vehicles needed to travel on firm roads, the British offered to pave his road and to make it their main access road. Chew generously permitted this, and in recognition of his donation, the British named the road after him.

Our trolley buses had now been replaced by wireless buses run by the Singapore Traction Company (STC) and a local businessman, Tay Koh Yat. As red was an auspicious colour in the Chinese ethos, the Tay Koh Yat buses were all red. Without the massive network of overhead cables that had been used for the trolley buses, our skies looked a lot tidier. But there was an increase in the number of posts for street lights and electrical wires, which were creeping out from the city towards rural areas. Those of us living in the kampongs watched this slow advance with excitement, because it would mean the end of having to use our temperamental generator, and we would have consistent electricity. When electricity finally arrived in our village, we really celebrated. The PAP had certainly fulfilled its rally promises, which made us so joyful. We felt eternally indebted.

My mother and I had to change buses to get to Katong. Once we got there, I immediately felt the change in the air and could smell the salt. I gulped the fresh air repeatedly like a fish out of water.

“What are you doing?” Mak asked.

I answered, “Makan angin.”

To makan is to eat. And angin means wind. It was a metaphor for going for a stroll outdoors or having leisure time. But I was purposely interpreting it literally in an attempt at humour.

Mak laughed. It was so lovely when she laughed. Her life was so hard that she did not have many such occasions.

“Di Tanjong Katong, airnya biru /At Tanjong Katong, where the water is blue...” she sang softly.

The song was one of our traditional songs, and she brought the words to life with her melodious voice. Like Karim, our village musician, my mother had an innate sense of rhythm and style. I felt happy and sang along with her as I skipped down the palm-tree lined coastal path. The wind blew my hair about and I tasted the salt in the air. I fell in love with the sea yet again. Perhaps it had something to do with the fact that my solar astrological sign was Pisces. I loved the way the sea whispered as its waves rolled in and out. I imagined they were trying to tell me of places they had been to around the world, so I listened hard. The sea gave me a yen for travel, another of my dreams.

Most of the houses by the sea were made of concrete and were magnificent. They were big bungalows on concrete plinths, with stone stairs that led down towards the sandy beach. Like the terraced houses in Joo Chiat, the houses had ornate decorative designs and were in colours that were typically Peranakan – pinks, turquoise-blues and greens, so much so that some of the houses looked like iced celebration cakes. They made the whole area seem cheery and friendly. The terraced shop-houses were on two floors and sold all sorts of Peranakan food, ingredients and wares. Mak was in her element. Her face brightened tremendously.

“We must buy some stangee,” she said. “And some bunga rampai.”

Stangee is incense that is made from an aromatic wood, and bunga rampai refers to a potpourri of the petals of various flowers and shredded pandan leaves, mixed with essential oils. Both are the Peranakans’ ways of keeping their homes smelling sweet and fragrant. Mak was in a celebratory mood and definitely feeling rich. Otherwise such luxuries were usually considered an extravagance.

At the corner of a row of shophouses, my mother treated me to traditional nonya laksa, noodles cooked in thick spicy coconut milk. We ate it with a spoon as it was the kampong way, though some people were beginning to adopt the Chinese way of using chopsticks.

At Joo Chiat, she trawled me through fabric shops and stalls in the market. She fingered numerous bolts of voile material. She was a skilful seamstress and could sew her own kebaya, though she would bring the completed kebaya back here to a specialist to ketok lobang. The latter was a row of fine holes, lobang in Malay, that were punctured into the fabric and they ran from the shoulder to the hem of the kebaya. They had no practical function but looked pretty. Either my mother or I would jait sulam, that is, embroider flowers and birds along the edges of the kebaya. It was a time-consuming process, so homemade kebayas tended to have just a simple row of embroidery. The more elaborate the embroidery was, the more valued the kebaya was deemed to be, as if it was a proof of the wealth of the people, who could afford to pay others to do it.

Finally she found a turquoise-blue fabric. She knew my father liked the colour on her. She found a batik sarong which had a pattern and colour which matched. We went home laden with our purchases, which included gula Melaka and flour for making the kuih baulu, kuih tart and kuih belanda, serai, lengkuas and daun limau perut, for the various sambals and curries. She was making all the various delicacies not just for our family but to distribute to the neighbours as well. My mother always put others first. But it was also a kampong tradition – the households celebrating their New Year would share their largess with close neighbours. This meant that we all joined in the celebration of the different races’ New Years, which created a very convivial atmosphere in our neighbourhood.

On this Chinese New Year, Mak surprised me by giving me a small pair of hooped gold earrings, which was such an extravagance. She must have got her senoman or tontine money, the scheme of saving money along with a group of people that villagers bought into.

“This is your Rabbit Year, so it’s a special gift.” She said. “By the time your next Rabbit Year comes, who knows where I will be.”

One of the delights of the Chinese New Year celebrations was the firing of red fire-crackers. If you laid your ears to the ground as I did when I slept on a mattress on the floor, the distant sound of the fire-crackers exploding was like the stampede of buffaloes. The Chinese fired crackers to scare the devils away from their homes. Because the fire-crackers were red and the colour was auspicious, when they splintered, they sent showers of red paper into the air, bringing good fortune into our lives. These were never swept away during the days of celebration. Besides, sweeping the floor on the first days of the New Year was considered bad luck, as it meant sweeping away good fortune from the home. The other delight was playing with bunga-api or flower-fire. These were thin wires of fireworks that were not explosive- they merely sizzled, and when we waved them around in the dark they created delightful trails of bright light.

On February 15, there was another cause for celebration in the country.

Television made its debut appearance. The thought of being able to view films in one’s home was a revolutionary idea. There was excitement in the air. A broadcasting station was set up and it was called TV Singapura.

My father took my mother, my two younger sisters and me to the inaugural telecast outside Victoria Memorial Hall. We went in a lorry together with other villagers from our kampong, which included Ah Gu, Krishnan and his family, Pak Osman, Karim, Abu, Fatima and their parents, and also Rajah and Salleh, my father’s weight-lifting mates. I managed to get a space for Parvathi, though her mother did not come. Wooden planks were placed across the back of the lorry and we used these as seats. As there was no back support, if the driver went too fast, we would sway dangerously, so we had to hold onto the planks tightly. But we had a jolly ride, Karim entertaining us with his guitar and songs, which we joined in when we knew the words.

“Long distance looking. That’s what tele-vision means,” Krishnan showed off his knowledge.

Of course, important people were invited to be inside Victoria Memorial Hall. We were told that there were seventeen television sets in the hall. We were standing outside, where a marquee had been erected to protect the sets that were placed outdoors for us. There were hundreds of people. Everyone jostled and craned their necks to look. It was not easy for me to see anything. My father carried one of my younger sisters on his shoulders and Ah Gu carried the other.

“What about me? What about me?” I cried.

Parvathi was taller than me so she had no difficulty in peering over heads and shoulders. I really did not want to miss out on the historic moment. Karim took pity on me and hauled me up onto his shoulders, and when my elder brothers turned up later, they swapped over.

The TV was switched on and a clock appeared in black-and-white.

Everyone applauded and shouted, “Hurray!”

The hands of the clock ticked towards six o’clock. Our eyes were riveted on the clock as if it was a hypnotist’s instrument. Then the clock faded and the Singapore flag appeared, but without colour, to the accompaniment of Majulah Singapura, the song composed by Encik Zubir Said, which was performed in public for the first time in that very hall. Everyone stood to attention and sang.

It was an emotional moment. Come August, we would be singing a different national anthem.

Culture Minister S. Rajaratnam appeared on screen and said in English, “Tonight might well mark the start of a social and cultural revolution in our lives.”

He was followed by a documentary programme, TV looks at Singapura. This was followed by a cartoon feature, then a newsreel and a comedy. We were so engrossed, we did not realise the passing of time. Before the telecast ended, four announcers spoke in the four official languages to give a summary of the next day’s programme. The whole thing lasted for an hour and forty minutes.

Of course, most people could not afford to buy a television. Certainly not many in our village could spend money that was meant to buy food. The Culture Ministry knew that the average citizen was not flush with wealth, so it proposed that bars, coffee-shops and restaurants should install TV sets for their customers. Transmission began with only one hour per day, but slowly the hours increased to four. People congregated at public eateries in the evening, where there was a TV set. The kids in our village acted as spies, and kept on the look-out to see which coffee shop or neighbour had bought a TV set, so that we could steal a view.

On my birthday in March, my father, who had never given me any presents before, surprised me by giving me one. It was a ten-cent stamp with a picture of a blue kingfisher, one of my favourite birds, on it. The thought went through my mind that it was a strange present.

“This is our new stamp which has just been issued,” he said proudly. “Look! There is no queen’s head on it anymore. From this month, all our stamps will feature local orchids, birds and fishes.”

The light bulb went on in my head. Ahhh! Another historic moment. It was not just about stamps. The change might seem insignificant but it was actually a huge step that marked the onward progress of our nation.

Television impacted our lives in a way we had never dreamed possible. Just as libraries, books and Rediffusion opened up new worlds to us, TV took us there on a daily basis. Up until then, the only newsreels we saw were at the cinema in Pathe News, which were screened before the cartoon and main feature. So if we did not go to see a film, the only reports we received were from the radio and newspapers. Now far-off places were brought into our living rooms – at least for those who could afford a television set.

When Prime Minster Lee Kuan Yew came home from London in July after successful constitutional negotiations regarding Singapore’s status within Malaysia, we could actually see the smiles and share in his triumph. It was due to this new medium that we could see Dr Martin Luther King deliver his speech to 250,000 people in Washington, USA, on August 28, starting with the words that became iconic, “I have a dream...”.

“Merdeka! Merdeka!”

The shouts echoed across the country when Malaysia finally became a reality. What we had hoped and dreamed of for years was finally realised. We felt an emotional charge for our country, and a sense of identity was forged. Sadly, our neighbour Brunei had opted out of the union. So our new nation was formed of Malaya, Sarawak, Sabah and ourselves. This great occasion was marked with a new flag.

There was rejoicing but there was also an increase in tension.

This was the beginning of an infection that spread. For some reason, some Malays began to believe that Singapore joining Malaysia was only for the improvement of the ethnic Chinese community, so the worm of tension grew between the two races. Luckily for us, in our kampong we separated political ideology from personal relationships. But in kampongs like Geylang Serai, people who had once looked upon the other as a brotherly neighbour now looked at people of different facial features and colour with suspicion. Having lived peacefully with each other for years, people now became aware of others as different. The rot had started.

On September 7 we saw a telecast that unsettled us. In Jakarta, Indonesia, Anti-Malaysia rioters burned down the British Embassy. And on September 24 two bombs went off in Singapore, then another in October, all in the Katong area. An innocent girl was killed near Jalan Eunos in another blast. People were thrown into a state of unease and questions arose: Why was this happening now, when we had achieved our country’s dream for independence? Why should our countries’ merger cause others to be so angry? What harm was this merger doing to them? Was the bombing the work of Anti-Malaysia saboteurs or a mad bomber? What were they trying to achieve?

In many ways, when we didn’t have television, the horror of an incident was not brought home to us so tangibly. But now the sight of moving images with all their sound and fury made it hard to escape the drama and pain of the people engaged in conflict. Technology was both a gift and a curse. One of the most terrible scenes to witness on television was the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy on November 22 that year. Though he was not our leader, through films and now television, we had come to regard him as a charismatic, popular president. On the small screen, we saw the presidential motorcade come into view, with the president in an open-topped car, his wife beside him. Huge crowds thronged the streets of Dallas. President Kennedy was waving, his face beaming with a big smile, his forelock sweeping across his brow. Then, in the next moment, three shots rang out, and the president slumped sideways into his wife’s lap. No one had registered what had taken place. The motorcade was still moving. Even Jackie Kennedy did not realise what had happened. She was nonplussed. Then, when realisation hit her, her face registered her anguish. Chaos reigned. And though we only saw it in black and white, we thought we saw the redness of his blood as it spattered on her face, hands, suit, and in her lap. The horror was indelibly etched in our minds. No one could have seen that scene and forgotten it. In May 1961, President Kennedy had vocalised his dream to Congress, of seeing the U.S.A. put a man on the moon. He would not see his dream fructify now.

Another horror lay in store for us – this time much closer to home.

The fifth bomb blast of the year occurred in December in Sennett Estate, the residential estate across Upper Serangoon Road directly opposite us in Kampong Potong Pasir. Someone threw the bomb across a rooftop. The bomb exploded. We all ran out of our houses when we heard the explosion.

“Sounds like war again,” Pak Osman said.

The older folks knew what had caused the explosion but we youngsters did not. The loud noise was scary. Luckily the bomb had skidded off and exploded in the garden, so no one was hurt. Still, it was a manifestation of the unrest that had begun. Our dream to be an independent country was not without its dark side.

Of course we did not know that this was only the beginning of more strife.