Chapter 21

On my way to the kitchen for more plastic bags for Mattie’s underclothes, sweaters, and so forth, I spoke to Mr. Wheeler, who was busy pushing aside furniture so Diane could get to the highboy against the back wall of the room.

“Oh, phoo,” Diane said as she slid behind the sofa to study the large piece up close. “I was afraid of this. It’s new. Well, not new,” she corrected herself, “but certainly not old. I thought it might be tiger maple, which would be a find, but the grain has been painted on.”

That was a disappointment, but I left them to it and met LuAnne at the hall doorway with a scowl on her face and a dress over her arm.

“I want another opinion,” she said, holding up a navy blue dress. “Look, everybody, what do you think of this for Mattie? I’ll tell you right now, it’s the best of the lot and if you don’t like it, I don’t know what I’ll do. Julia won’t let me buy her anything.”

“LuAnne!” I said, just so put out that she was blaming me for the state of Mattie’s wardrobe. “It’s not my money to throw around. And I think that dress is perfectly fine.”

Helen said, “I think Mattie wore it at the last book club meeting at my house. She looked very nice in it.”

I nodded my thanks to Helen, while Diane, who hadn’t ever seen Mattie in anything, agreed that the navy blue frock was suitable attire for a viewing. Mr. Wheeler just smiled and offered no opinion.

“Some pearls would look nice with it,” Helen said, which gave LuAnne another opportunity to disparage me.

“Well,” she said, “Julia’s already packed up all of Mattie’s jewelry and gotten rid of it.”

“No, LuAnne, no,” I said tiredly. “It’s locked in the trunk of my car, waiting to be taken to Benson’s. We can walk out together and you can look through it. There’re several strands of pearls to choose from.”

“Well, okay,” she said, “but you better not let them get buried with her.”

“They won’t. The funeral home people will give them to you when the visitation is over. You can get them back to me so they can be appraised.”

“Well, what about the service on Friday?” LuAnne demanded. “Don’t you want her to look nice at church?”

“LuAnne, please. I thought you’d agreed not to have an open casket at the church. In fact, I’d as soon not have the casket there at all.”

“I’ve never heard of anybody being absent for their own funeral,” LuAnne said. “I think Pastor Ledbetter is expecting her to be there.”

“Fine,” I said. “Whatever you two decide will be fine. Now let’s go find some pearls so we can get her dressed.”

_______

The rest of the afternoon was mostly taken up with getting Mattie’s wardrobe off the bed and out to the Goodwill store on the boulevard. By the time I straightened the clothes that LuAnne had picked through—leaving a jumble on the bed—I decided to leave the winter clothes in the guest room for another time. What I had was enough to fill the backseat and the trunk of my car, anyway.

Mr. Wheeler had been kind enough to help me load up the car, although I had been careful to gather up Mattie’s underclothes myself. I didn’t want to embarrass the man by saddling him with her huge pink brassieres.

After getting a tax form from Goodwill, which from the state of Mattie’s clothing I didn’t think was worth filling out, I found a parking spot in front of Benson’s. Running in with a sack full of jewelry, I told the appraiser, “Just do the best you can. It’s vintage, if that helps.”

Then I went to the First National Bank to open Mattie’s safe-deposit box.

Upon presentation of my papers of authority, I was ushered to a small cubicle and left alone with her lockbox. Hoping against hope for some wonderful source of funds, I found several things of interest, but none of value. There was a birth certificate for Mattie Iona Cobb, born in 1931 in Versailles, Kentucky, as well as a few outdated and canceled documents—old stock certificates and the like—made out to Mattie Cobb Freeman and one Thomas Edgar Freeman. And right at the bottom, I found a death certificate along with a wrinkled photograph wrapped in tissue paper. It showed a piercingly young man in an army uniform with the name Tommy written in pencil on the back. Glancing at the date of death on the certificate, I saw that Mattie had been a widow much longer than she’d been a wife.

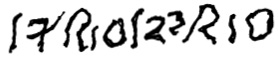

Sighing, I looked through everything again to be sure that I’d not overlooked anything. And a good thing I did, because there was a small ziplock bag stuck in the folds of a canceled deed. In it was half of a torn index card with a string of indecipherable—at least, by me—letters and numbers written in ink by a shaky hand. Under my breath, I read what I could make out

“El seven—the European way, or maybe seventeen—RIO, el two, superscript three, and RIO again.”

Vaguely wondering why Mattie had not only saved, but also locked away, a meaningless scribble, I put it back in its ziplock bag and stuck it in my purse. Perhaps, I thought, it had been Tommy’s army identification number when his body had been shipped home. That which seems of no account to one person could be precious to someone else.

I carefully stacked everything together to eventually take to Mr. Sitton. Then I told the teller that Mrs. Freeman no longer needed her lockbox and asked about a refund on the rental.

Tired and hungry by that time, I had to swing back by the apartment to lock up behind Helen and Diane, both of whom said they’d be back the following afternoon. Afternoons were the only times that either of them could give to Mattie’s furniture—both had part-time jobs that took up the mornings. I didn’t like it, but had to take what I could get.

Diane had made a cursory examination of the contents of the living room, but she still needed to examine the Charleston rice bed and the highboy in the bedroom, which had a tantalizingly eighteenth-century-looking patina, as well as the Oriental rugs throughout the apartment. Then there were several old portraits on the walls, which she said would have to be looked at by an art expert. “But,” she’d said with a wry smile, “I don’t have much hope for them unless somebody at auction is looking for ancestors—anybody’s ancestors.”

I didn’t have much hope along those lines, either, for all I’d seen had been faded photographic portraits of fierce, bearded men and thin-lipped women with high collars.

Hurrying home to have dinner with Sam, I knew I’d have to listen to Lillian tell me that everything didn’t have to be done in one week. But I wanted it done, and done as quickly as possible. Mattie’s estate had already taken over my life and I was tired of it.

Nonetheless, Lillian started in as soon as I came through the door. “You gonna make yourself sick, runnin’ ’round tryin’ to do it all at one time. What’s the hurry? Miss Mattie don’t care when it get done.”

“I know, Lillian, but there’s not enough money for me to fiddle around paying unnecessary rent on her apartment.”

“Huh,” Lillian said, almost, but not quite, under her breath. “You don’t have to tell me ’bout payin’ no rent. Pore ole Reverend Abernathy don’t know what to do, ’cept ev’rybody in the church tellin’ him what he ought to do.”

“Oh, yes,” I said, taking my place at the table and smiling at Sam. “You started tellin’ me about that. What’s going on with the reverend and who was it? Mr. Mobley?”

“Mr. Robert Mobley, yes, ma’am. That’s who got it started, all right. But I got to get this gravy stirred ’fore it’s too lumpy to eat.”

So as we ate, Sam and I chatted about our day, catching up with each other. Sam confirmed that he’d agreed to serve as a pallbearer, and I gave him a blow-by-blow account of LuAnne’s search for the proper funeral attire, along with an update of Diane’s discoveries.

“She thinks it’s worth having somebody from a big auction house in Atlanta come up and get it all. She says even the reproductions will have a better chance there than trying to contact individual dealers around here.”

“That sounds encouraging,” Sam said. “With all the furniture gone, you can have the apartment cleaned, then give up the lease. That’ll be a huge step forward for you.”

“Well, I was a little concerned about letting a stranger from Atlanta just come in and carry everything off. Who knows how honest he’d be when things were auctioned? But Diane is taking pictures of each piece, and she’s going to be there when the lot comes up for auction. So that’s one big worry off my mind. I think Helen might go with her.

“Oh, Sam,” I said, leaning my head on my hand—an elbow on the table was fine under the circumstances. “I hope I’m doing things right, but it seems just one thing after another.”

“You are, honey. Nobody could do it better. But Lillian is right. You don’t need to push yourself.”

“I know, but if I can get through the visitation and the funeral, and get Mildred home and started on a fitness routine, I’ll rest easier.”

We both turned from the table as the telephone rang. “Suppertime,” I said wearily. “Who calls at suppertime except fund-raisers or bad news?”

I wished it had been a fund-raiser. When Lillian answered the phone and told the caller that I was having dinner, she listened for a minute, then said, “Yes, sir, I b’lieve she can.”

Frowning, she handed the phone to me. “When a lawyer call, it worth interruptin’ your supper.”

“Mrs. Murdoch,” Mr. Ernest Sitton said when I answered, “I have unexpected news, and I recommend that we both tread carefully until I’ve had the opportunity to look further into it.”

What in the world? I looked worriedly at Sam while responding carefully to Mr. Sitton. “It doesn’t sound exactly like good news, Mr. Sitton. What is it?”

“An apparent distant relative of Mattie Freeman came to my office late this afternoon. Seemed personable enough, but of course we need to confirm his relation to her, if indeed there is any.”

I glanced at Sam, wishing he could hear what I was hearing, which I thought was more than a tinge of caution in Mr. Sitton’s words.

“Did he say what he wanted?” I asked, as if I couldn’t guess.

“Well, that’s the thing,” Mr. Sitton said. “He immediately announced that he’d never known Mrs. Freeman, and he doubted that she knew he even existed. Referring, it seemed, now and then to some huge family breakup. But he’d heard of her through family stories and had always planned to visit and get to know her. He seemed to truly regret his late arrival. But he said he’s been on the road, traveling and living from hand to mouth for a long time. He assured me that he had no intention of contesting, or even questioning, any estate plan she’d made. He said, ‘I don’t expect anything and I don’t want anything.’ Then he went on to tell me what he did want.”

“Oh, me,” I said, foreseeing lawsuits and disappointments and wranglings over reproductions and paste jewelry and the minimal amounts of money in Mattie’s accounts. “What was it?”

“Family memorabilia. He wants to look through Ms. Freeman’s apartment for scrapbooks, letters, and pictures because he has plans to write a family history. And, interestingly enough, he also asked for a sample of Ms. Freeman’s needlework as a memento. He said that he grew up hearing about the expertise of Cobb women in handiwork of one kind or another—a family tradition, so to speak, with Aunt Mattie, according to family lore, being the most artistic and proficient. Anyway, I put him off until I could speak with you. What do you think?”

“Lord, Mr. Sitton, I don’t know.” I looked at Sam again, longing to talk with him. “Well, I do know, too. I say we don’t let him have access to anything until you confirm that he is who he says he is. And, as far as Mattie’s skill in needlework, be it embroidery or needlepoint or cross-stitch, is concerned, I have never seen her with so much as a thimble on a finger. Nor have I seen even a sewing basket in her apartment. But, then,” I said, pausing to consider, “her eyesight hasn’t been good for years. Maybe she had to give it up.”

Then, suddenly making a startling, though delayed, connection, I said, “Wait! Did you say the man’s name is Cobb? Mr. Sitton, that was Mattie’s maiden name.”

Sam’s eyebrows went straight up.

Mr. Sitton said, “Yes, I’m aware of that. Nonetheless, red flags went up when he asked if he could stay in his great-aunt’s house—that’s what he called her, his great-aunt. I had to explain that she’d lived in a rented apartment and had never owned a house. Didn’t want to tantalize him, don’t you know.”

“Oh, you’re right. He can’t stay in her apartment. We’ll be moving the furniture out in the next week or so. Besides, we haven’t gone through everything yet, and I don’t want a strange man scrounging around in there before we do.”

“Absolutely. He has a place to stay, anyway. He’s living in what he called an Airstream Sport trailer, by which I know to mean an aluminum two-wheeled trailer hitched to the back of his car. He apparently has it unhooked now and parked out at Walmart.

“So my feeling is that if it’s been good enough for him so far, he can continue to stay in it. I just wanted to warn you that he might show up at the apartment while you’re there. And, Mrs. Murdoch, to warn you that he can be quite engaging, and we must also keep in mind that he might indeed be who he says he is.”

When we finally hung up, I turned to Sam and said, “Well, wouldn’t you know it? An even bigger problem has just reared its ugly head.”