Convenience or Contraption

Electric Lighting

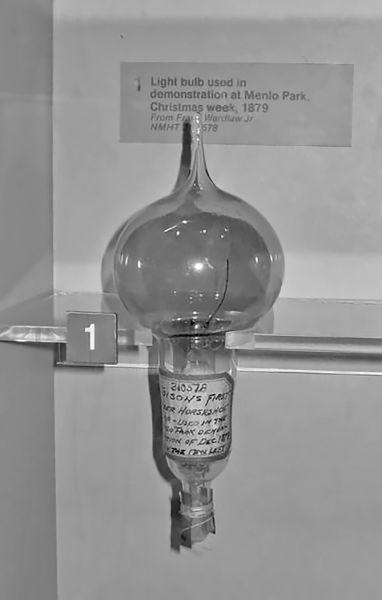

Nothing short of a miracle was expected when, in 1878, the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” Thomas Alva Edison, announced his plan to develop an incandescent lightbulb that would glow brightly in New York’s Gilded Age. Soon, he proposed, the city’s homes, restaurants, hotels, and shops would be freed from a dependence on gas light, the onetime boon that had supplanted wax candles and kerosene lamps but left walls and ceilings blackened with soot and caused headaches from the gas vapors of ammonia, carbon dioxide, and sulfur, while oxygen was sucked from the air. Declared the Gilded Age interior designer Elsie De Wolfe, “Gas lamps are hideous.” Edison promised mellow lighting that was clean and long lasting. The market would be huge and consumer demand inexhaustible.

Gilded Age capitalists, including the Vanderbilt men and J. P. Morgan, promptly formed the Edison Electric Light Company, issued stock, and forwarded $50,000 to Edison to fund his experiments. The workshop and library at Edison’s New Jersey headquarters swelled with new employees, and in the following year, investors were invited to Menlo Park to witness the demonstration of electric globes that glowed evenly with the same luminosity as a gas jet for over thirteen hours. The race to light up New York and all of America was under way.

The demonstration showed Edison’s genius as an entrepreneur and marketer. Other names crowd the histories of the technical development of electric power and light, some of them American, others British or European. The sole name on Americans’ lips, however, was Edison.

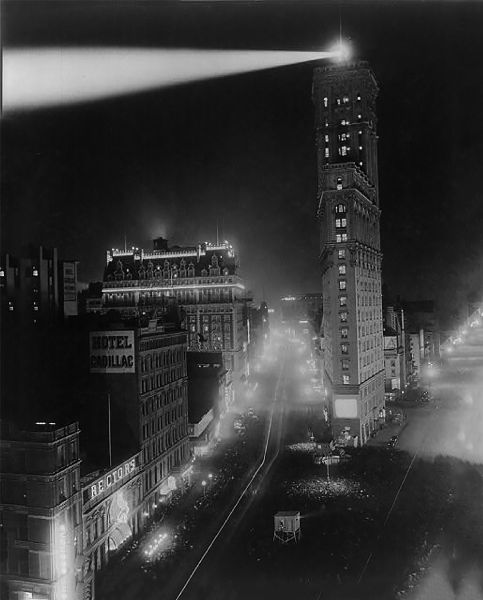

One competitor and contemporary of Edison deserved a close watch at the time and notice today. Charles Brush (b. 1849) was a Cleveland farm boy whose tinkering led to the development of an efficient power-generating dynamo and a blazing bright light called arc light. Named for the discharge, or arc, that occurs when gas gains or loses electrons and is subject to a high-voltage pulse, the arc light could turn nighttime city streets into broad daylight, as the twenty-nine-year-old Brush demonstrated in downtown Cleveland. Soon the Brush Electric Light Company was under contract by the New York City Gas Commission to construct the generating station that powered a series of arc lights mounted atop twenty-foot cast-iron posts on each block from the lower end of Union Square to Madison Square.

The arc lights that blazed forth in December 1880 lit up Broadway’s “Great White Way.” And they were also installed the next year in Union Square, where the sculptor Augustus St. Gaudens’s statue Diana the Huntress was mounted atop a tower across from Delmonico’s. As the unveiling on the second of November drew near, rumors spread that the goddess was nude to the waist. A crowd gathered by early afternoon, some equipped with field glasses, until, at five p.m., workmen released the cords of the muslin sheets that covered the statue to reveal Diana (reported the Herald, “in all her nudity”). At 5:15, the lights blazed, and awed spectators were dazzled by “incandescent bulbs strung about her head and outlining her bow and arrow, while giant searchlights”—arc lights—“bathed her in their glow.”

The electrification of New York City became a tangled tale of turf wars, of rival electric companies, cost overruns, and utility poles supporting a thick web of overhead wires that collapsed in winter ice storms and whipped like snakes on the streets until the power was cut. In 1884, the legislature mandated that electrical wiring be set underground, and Edison’s workers dug trenches to bury the heavily insulated wires. The electrification of New York City is also the story of a scientific contest, with Edison’s direct electrical current losing out to George Westinghouse’s promotion of the more efficient alternating current that could be stepped up or reduced in power, depending on demand. The “Wizard of Menlo Park” continued to be the name synonymous with electric light, but the name Westinghouse was consolidated with rival firms to become General Electric, a financial arrangement that was contrived by J. P. Morgan, another “wizard” of the Gilded Age.

Gotham’s moguls themselves were early adopters. J. P. Morgan’s mansion was the first private residence converted to incandescent lighting, and the Vanderbilts soon had all three of their uptown homes wired as well. The New York Stock Exchange was electrified, and by 1883, five hundred homes of the city’s rich glowed with incandescent lighting. (To them, the initial $1 price of a bulb—nearly $28 today—was a trifle.) Prestigious hotels were also modernized. Visiting New York in 1893, the French journalist Paul Bourget marveled that his room was outfitted with “electric lights” to its “utmost corner,” with electricity powering “everything . . . from the bells to the clocks.” Industry was onboard, as night shifts guaranteed round-the-clock output.

Night life surged, as pedestrians basked in the light pouring out from blocks of cafés and restaurants that lined the streets. Electrically lighted signs spread outward from the Great White Way, and incandescent lighting partnered with plate-glass windows to make storefront displays beckon in the late evening hours. When Mrs. Astor dined at Sherry’s, the ambiance was aglow with a “cluster of lights—incandescent globes,” in the words of the novelist Theodore Dreiser. And in Edward Bellamy’s wildly popular utopian novel Looking Backward—America 2000–1887 (1888), electrical power is used freely to generate everything from indoor lighting to recorded music. Electrical appliances followed household lighting, beginning with the fan around 1880 and progressing to the electric toaster, waffle iron, hotplate, and electric iron (about 1905). Electric vacuum cleaners appeared in the 1910s, and electric sewing machines soon replaced the foot-powered treadles.

Indoor lighting, however, proved challenging. Arc lighting had already been shown to be too harsh for indoor space, even in large public areas when opalescent glass globes covered the lights. It cast human faces in a ghoulish pallor while exposing every line and blemish. It killed the appetite, and the lights audibly buzzed. Incandescent bulbs were a great improvement, but—too few or too many—could produce gloom or glare. Edith Wharton lambasted modern hotels for their “torrid splendor,” and her novel The House of Mirth (1905) targeted the typically ornate wall sconces (“ornamental excrescences”) in the suite of a clueless rich divorcée who, sad to say, dwells unselfconsciously in the “blaze of light.” Wharton redoubled her attack in The Custom of the Country (1913) when she compared the “crude” beauty of a ruthlessly ambitious midwestern young woman to the “glare” of the electric lights.

Railing at wretched lighting in fiction was the novelist’s sport, but an interior designer must please demanding clients with electrical lighting that served a panoply of purposes. It must flatter spaces and human faces and provide illumination for reading or bridge, a favorite pastime of the Four Hundred. It must highlight objets d’art, family portraits, and precious collections shelved in niches or wall mounted, from porcelain bibelots to military muskets. The designer Elsie De Wolfe devoted an entire chapter—“The Problem of Artificial Light”—to the challenges she encountered in decades of furnishing and lighting townhouses, country houses, and mansions.

In The House in Good Taste (1913), De Wolfe recaps the rigors of pleasing a clientele of such socially prominent ladies as the Colony Club members Mrs. Henry Clews, Miss Margaret Chanler, and Mrs. J. J. (John Jacob) Astor. “In all the equipment of the modern house,” De Wolfe begins, “there is nothing more difficult than the problem of artificial light.” She admitted that “the clear, white light of electricity seems heaven-sent when one is dressing or working,” but achieving the “glow” and avoiding the “glare” required skill and planning. Electrical sockets (“openings”), for instance, needed strategic placement for lamps and wall sconces. Oftentimes, De Wolfe lamented, she arrived too late on the scene, when the wiring was already in place, that is, misplaced. Many a “good room” was spoiled by “too high” sockets. Her advice: put “a liberal number of base openings in a room, for it costs little when the room is in embryo.”

De Wolfe offered advice on lamps, chandeliers, and wall fixtures. Closing her discussion, however, she surely took her clients by surprise. Her highest standard for the most humanly appealing lighting was none other than “the glow of an open fire.”

Elevators

Wild beasts and gladiators were hoisted to the Coliseum arena as far back as 80 AD, but businessmen on upper floors and ladies shopping in the multistory department stores of the “Ladies Mile” in Gilded Age New York owe a debt to Elisha Graves Otis (b. 1811). The young Vermont mechanic was tasked by his employer, a bedstead manufacturer, to devise a freight elevator that could overcome a fatal flaw that persisted through centuries of mechanical hoists. Quite simply, the freight would plunge to earth upon the failure of a lifting rope or cable. In 1852, Otis invented a “safety hoister” utilizing a wagon spring, a ratchet bar, and guide rails. If the cable broke, the spring tension would instantly release to hold the freight platform in place. The following year, Otis launched the company based on his “safety brake.” Hydraulic power was replaced by electricity as of 1889, when motors powered the cars upward while steel cables connected to counterweights with pulley arrangements enabled the elevator car to ascend and descend. The name Otis became a byword for elevator safety.

By the 1890s, visitors to American shores marveled at the newest Gotham hotels of ten, twelve, fourteen stories, called “sky scrapers” and “cloud-pressers,” their elevators “ready to mount up with the rapidity of an electric dispatch.” Day or night, electric elevators whisked passengers to unprecedented heights and deftly delivered them to earth. Uniformed employees operated the controls inside the car, often in brass-buttoned tunics resembling military garb. Responsible for the passengers’ safety, they issued commands (“step lively” or “watch the doors”) and announced the floors (“Fourth floor—linens” or “Second floor—Cadwalader Insurance Agency”) and guided the elevators to the exact floor level, as if docking a ship so precisely that all passengers could disembark without losing a step—or tripping.

The elevator interiors were often paneled, and the visiting British journalist George Sala recalled “a Turkey-carpeted, bird’s-eye maple and plate-glass lined elevator” in a hotel of the “Empire City.” Some had bench seats. Above all, passengers must not be reminded that they were being hoisted up and down in something like a cage. (Andrew Carnegie enjoyed an elevator in his mansion at Fifth Avenue and East Ninety-First Street.)

“The great religion of the Elevator” rankled Henry James, who was appalled at the new high-rise New York he visited in 1904 after an absence of twenty years. He minced no words about “the packed and hoisted basket.” The mechanism worked “fearfully and wonderfully,” but James felt “pushed and pressed in,” his shoulders and heels dodging “something that slides or slams or bangs.” Both “the Elevated and the Elevator,” he decided, were “an intolerable symbol of the herded and driven state” of modern life.

Mark Twain, however, took the opposite view. His after-dinner speech at Delmonico’s in December 1900 paid tribute to the excellence of New York City and extolled the wonders of its new “fairylike,” “enchanting” nighttime skyline. “What has made these skyscrapers possible,” proclaimed Twain, “is the elevator.”

Telephone

In August 1882, Alexander Graham Bell and his daughters visited Newport, the summer capital of Society, but found it nearly impossible to find overnight lodgings. There were no hotels, and no owner of a mansion-sized “cottage” offered to host them. Six years earlier, Bell had patented the telephone, an instrument that electrically transmitted the human voice over distances, but like his invention, the telephone, he had not been fully admitted into Society.

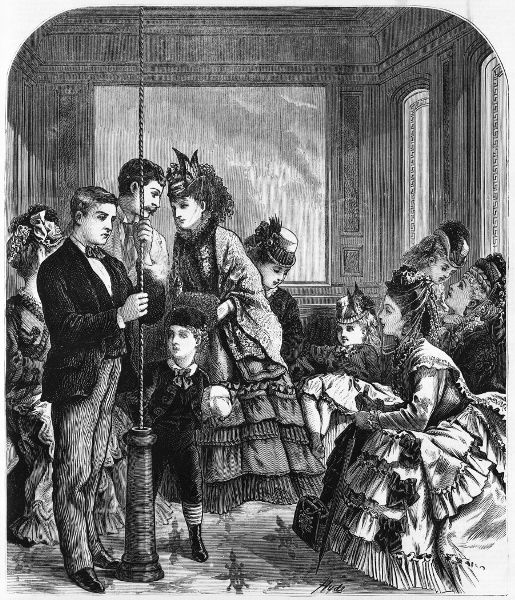

In the early 1880s, a clever electric buzzer installed in the home could summon a Western Union messenger to take a dispatch to be telegraphed. Etiquette, what is more, demanded that social messages such as invitations or birth announcements be written by hand on quality stationery and sent by the US Post Office or by a messenger.

A system of patented battery-powered pull bells or buttons could summon servants within the household of an affluent family in Gilded Age New York, but the notion of a sudden ringing bell that interrupted a visit or a conversation, let alone a meal at a dining table, was simply out of the question.

In the Wall Street offices of the railroad financier Clarence Day Sr. (b. 1844), one of the devices had been tucked out of sight in a back room, where the bookkeeper “dealt with it . . . bringing [Day] the message if necessary,” but “the idea of putting these business conveniences in a home seemed absurd.” And the electricity, dangerous! Day’s wife, Vinnie, agreed. She distrusted telephones because “they weren’t human.” They “made her nervous.” Besides, “she had to see the face of any person she talked to. She didn’t want to be answered by a voice coming out of a box on the wall.” “People admitted that telephones were ingenious contraptions,” recalled the New Yorker Clarence Day Jr. (b. 1874), “but they no more thought of getting one than of buying . . . a diving suit.”

The telephone, nonetheless, was on its way. By the late 1880s, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company was sending advertising circulars that made “large claims”: “an important department store now had a telephone, and three banks had ordered one apiece, and some enterprising doctors were getting them.” Grocers installed them, as did livery stables and druggists. Mark Twain’s best-selling time-travel novel of 1889, A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court, featured a telephone system installed in Arthurian Camelot and a baby girl named “Hello Central,” echoing the greeting from the telephone exchanges where banks of young women seated at switchboards connected the swelling ranks of callers. In the well-respected Occupations for Women (1897), the temperance movement leader Frances Willard listed the weekly salary of a “Telephone Girl”—$7 to $10 for a local switchboard, $12 to $15 for long distance, the equivalent range of $230 to $430 today. A Telephone Girl must be patient, “quick and bright,” Willard advised, with “an utter absence of nerves.” A Girl who “flies to pieces under pressure” is “worse than useless in a telephone office.”

Ultimately the Clarence Day family relented as Father saw the convenience of the telephone and Mother overcame her objections. Installed on an upper floor of their Madison Square home, the ringing phone was at first “rude and intrusive.” “Mother would pick up her skirts and run upstairs, calling to it loudly, ‘I’m coming.’” Father refused to be hurried, “but he scolded and cursed it.” Clarence Jr. recalled mismatched phone conversations that were pure slapstick comedy. To the very last, Father threatened, “I’ll have the confounded thing taken out,” but the phone was home to stay, not only in Gilded Age mansions but in more modest homes across America. In 1897, the Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalogue offered a wall-mounted “Improved Long Distance battery telephone” for $13.50 (about $400 today). The consumer had a choice of cabinetry, solid oak or walnut.