Best Dressed

The Hat Makes the Man

Each business day, a throng of “silk-hatted” New York businessmen could be seen “politely shoving each other” at the doorway of Delmonico’s restaurant at 2 William Street (the corner of Beaver and William) as they sought to exit the establishment. “Lunching in a lingering way,” the gentlemen suddenly remembered that “they were due back in Wall Street,” and they scrambled to reclaim the “plush” silk high hats they had checked at the door. No gentleman would have been so clueless as to appear outside bareheaded or so gauche as to dine while wearing his hat.

The high hat—a tall, flat-crowned, broad-brimmed chapeau otherwise known as the top hat, cylinder hat, chimney pot, stove pipe, or “topper”—emerged in the late 1700s to supplant the dated, flat-crowned tricorne. The newer style of hat was constructed of wool or felted fur, usually beaver, draped over a shell, then topped with fur or silk plush and heated to fix the shape. Once the hat was “rested,” the brim was curled and bound with grosgrain silk ribbon with a band of silk installed around the base. Finally, the lining was hand stitched and a leather sweatband applied.

By the decades of the Gilded Age, gentlemen’s high hats varied slightly in shape, the “chimney pot” sides now slightly concave, while the traditional stovepipe crown remained straight sided. (Abraham Lincoln popularized the stovepipe, and the American figure of Uncle Sam in red, white, and blue is often portrayed in such a topper.) Despite working-class men’s attraction to cheap felt “stuff” imitations, the Gilded Age high hat signified upper-class urbane respectability and wealth. It was to survive far into the twentieth century in rituals of diplomacy, state funerals, weddings, and equestrian events such as the English Ascot Thoroughbred races annually in June and July. (President John F. Kennedy wore a high hat to his inauguration in January 1961.)

Lest one imagine that the tricorne of yore was forgotten in the Gilded Age, the triangular chapeau lived on in oil paintings adorning the walls of the finest Gilded Age domiciles, including the premier space of Mrs. Astor’s ballroom. In addition, socially prominent men, such as the Equitable Life Assurance Company heir James Hazen Hyde, donned fur-trimmed tricorne hats for Hyde’s French Versailles-themed costume ball at Sherry’s, where six hundred guests reveled nightlong as courtiers and ladies in the restaurant’s two ballrooms and garden. The next day, rested from the festivities, the courtiers swapped the tricornes for high hats befitting gentlemen of their rank.

When inclement weather threatened to ruin a silk high hat on an overcast day, businessmen resorted to umbrellas—and derby hats. Named for the twelfth Earl of Derby, who organized a prominent racing event called the Epsom Derby, later emulated by its counterpart in Kentucky, the bowler was the requisite headwear of the stylish Englishmen. With a signature rounded crown, the hard-felt derby was durable and practical (shaped by steam pressing wool felt cloth laid over a metal form). Unlike the high hat, it need not be doffed to evade low-hanging tree branches or doorways, nor would a sudden gust of wind dislodge it. The hat crossed the pond to America in the 1860s and was popular throughout the Gilded Age. Also known as the bombin or bob hat, the ubiquitous derby was sighted everywhere—on the pathways of Central Park, on liverymen at work in stables, and on cadres of jobless men who constituted themselves as “Coxey’s Army” and marched from Ohio to Washington, DC, to petition Congress for help in the depression year of 1894.

The versatile derby remained gentlemen’s favorite, whether for the workplace, informal occasions, or recreational venues such as baseball games or prizefights. The New York Railroad executive Clarence Day Sr. donned a derby to take Clarence Jr. to the Buffalo Bill show one Saturday afternoon in 1886.

Seasonal warm weather brought the men’s straw “skimmer” to the fore. Otherwise dubbed a straw boater or basher, this headwear was, paradoxically, formal wear for informal events, such as an afternoon of yachting or a game of croquet. It might be worn with a blazer or a lounge suit or at a black-tie, rather than white-tie, event. With a stiff brim and low, flat crown, the straw skimmer was relatively cool in the summertime when sea breezes, fans, and iced drinks were the only available coolants.

By custom, many eastern cities designated an annual late-spring “straw hat day” to inaugurate the summer season. At Newport’s exclusive Bailey’s Beach in the Gilded Age, Mr. James Van Alen “always went into the sea in the full glory of a monocle and white straw hat which glimmered in the sun, thus proclaiming his whereabouts.” A good many men wore straw “skimmer” hats to welcome the RMS Lusitania into New York Harbor on her maiden voyage, September 1907.

Variations of the skimmer, styled with more shapely brims and crowns and of superior quality, were (and are to this day) produced in and imported from Ecuador, whose skilled hat makers deftly produce weft-and-weave patterns from the jipijapa or the toquilla palms. After President Theodore Roosevelt donned one while visiting a construction site for the new “canal between the seas” in 1904, they became known by the misnomer “Panama hats.”

Further down the social scale, the workmen’s flat cap, worn by boys and men alike, signaled a wide range of occupations in the Gilded Age. Made of tweed, corduroy, or broadcloth, the caps were a staple for the street urchins peddling the New York World or Herald on city street corners, the working stiffs striding the high steel beams on construction sites, or the dockworkers hoisting the trunks of a Gilded Age family en route to Newport. With calloused hands, these men donned and doffed this one-and-only cap.

Figure 13. Clockwise from top left: top hat, derby, cap, skimmer

Although the newsy is often solely associated with the lower classes, a bourgeois or upper-class boy often was outfitted in a similar cap. Of course, his was not soiled and tattered. Such was the case when young Clarence Day was treated to the Buffalo Bill show by his father, who noticed the lad’s cap askew. “Put your cap on straight,” ordered Father. “I am trying to bring you up to be a civilized man.”

The Walking Stick: The Essential Gentleman’s Accessory

Stepping outdoors on a sunny day in 1880s New York City, Clarence Day Sr. “wore a silk hat and carried a cane, like his friends. When he and they passed each other on the street, they raised their canes and touched the brims of their hats with them, in formal salute.” Walking with Clarence Sr., twelve-year-old Clarence Jr. lamented, “I was too young for a cane.”

In truth, young Clarence more precisely referred to the New York gentlemen’s walking stick. Although “stick” and “cane” were at times interchangeable terms, a distinction between them in the Gilded Age held the walking stick to be a fashion accessory, the cane an appliance for pedestrian assistance. A further distinction was based on the quality of materials: canes were fashioned from rattan, bamboo, and other plentiful low-cost materials; sticks from such finer, costlier goods as ivory or ebony. Social distinction followed the hierarchy of materials. Mr. Day and his friends saluted one another with sticks signifying their status and wealth.

These gentlemen traced their ancestry to colonial New England or Dutch New York, and they carried tradition along with their sticks. Walking sticks were a necessary fashion accessory in eighteenth-century Britain and Europe, where stern rules of etiquette prevailed. In London, where a license was required to carry either a cane or a walking stick, one such passage stated, “You are hereby required to permit the bearer of this cane to pass and repass through the streets of London, or anyplace within ten miles of it, without theft or molestation: Provided that he does not walk with it under his arm [or] brandish it in the air . . . in which case it shall be forfeited.” US presidents often carried canes, and they both gave and received them as gifts, such as a gold-handled cane that Benjamin Franklin proffered to George Washington, with a distinguishing French Liberty cap.

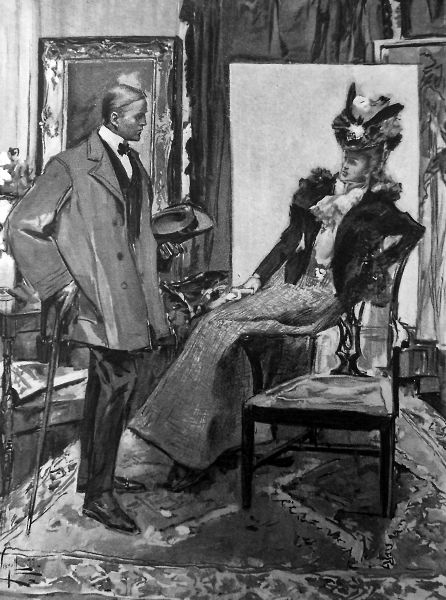

Figure 14. His walking stick, her feathered hat—and off they go

An even longer history of Gilded Age New Yorkers’ walking sticks was, in fact, on display within walking distance. They needed only to visit the new Metropolitan Museum of Art at 681 Fifth Avenue. Opened in 1872 and funded by such gentlemen as themselves, it exhibited artifacts from ancient Egypt that linked their sticks to a most ancient class of pharaohs, whose rule was signified by staffs topped with ornamental lotus knobs, a symbol of long life. And though suits of armor in the Metropolitan’s exhibition of the chivalric medieval period (and in Mr. Oliver Belmont’s private collection) surely caught gentlemen’s fancy, they could also note that a scepter carried in the right hand symbolized royal power. (From time to time, women also carried walking sticks or canes as a fashion accessory, as did Marie Antoinette.)

Canes carried some sinister associations as well. “Caning” was a type of corporal punishment, and hidden features such as sword points raised suspicions that a cane was a weapon in disguise. Indeed, a stout cane was a potential deadly weapon. At a dinner given at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in September 1903, attendees heard Earl Rogers, the celebrated Los Angeles criminal defense attorney, relate the case of a client who had been found not guilty of shooting a “gentleman” who threatened his life by beating him with his cane. No such scandals of canes or walking sticks beset New York of the Gilded Age, however, as propriety reigned daily and year-round.

The Plume Trade, or, Decorating with Nature

One feels tempted to leave to . . . the daily press the question of high hats and bonnets worn . . . in this season of extraordinary wings.

—Mrs. Burton Harrison, The Well-Bred Girl in Society, 1898

During the Gilded Age, milady’s chapeaux were a visual feast, a tottering assemblage of satin and silk, ribbon and lace, velvet and chiffon. Bows were a staple, pleats the norm, and the violets or roses on ladies’ hats were trompe l’oeil wonders. Built on frames of wire mesh and fixed in place on the head with inches-long stick pins, these sculptural compositions topped waves of upswept hair to ride aloft on ladies’ crowns. Every doyenne of the Four Hundred relied on her milliner to command the dexterity and imagination to accommodate personal taste, to provide helpings of well-timed flattery, and to align the seasonal offerings with fashion at its leading edge.

Quite naturally, an etiquette of headwear arose. Disputes centered on the propriety of hats worn indoors while paying calls or hosting visitors. At evening events such as the theater, it was “not desirable” to display “gowns or bonnets” in a private box. As for young women’s attractiveness in the orchestra or loge, “a very little consideration” would suffice, thus the suggestion “to leave off a bunch of ribbons here, a cluster of feathers or flowers there.” Such “abbreviation” would win the gratitude of “scores of seat-holders” and no way “impair the brightness of the eyes and cheeks beneath the headgear.”

One etiquette manual lashed out at ornate hats as “the milliner’s nightmare,” but the successful Gilded Age proprietor was a shrewd businesswoman. Her backroom “girls” assembled the customized creations for hourly wages, while at the front of the house, a boutique showroom was outfitted with mirrors for clients’ fittings and reveals. Certain Gilded Age ladies were millinery hobbyists. One of their set, Edith Wharton, used hat making to score a point in her debut novel, The House of Mirth (1905). When Wharton’s lead character, Miss Lily Bart, falls on hard times and must earn a living, she recalls dabbling in hats, “something that her charming listless hands could actually do.” Alas, her “untutored fingers” are no match for the milliner’s cadre of “experienced workers.” For Miss Bart, the elementary sewing of “over-lapping spangles” on wire frames proves impossible. Her abject failure at the craft amuses snickering shop girls who are “entrusted with the delicate art of shaping and trimming the hat.”

Wharton also pricked a socially fraught issue when she described showroom hats “perched on their stands like birds just poising for flight.” The ornithological jibe referred to a decades-long conflict that had roiled the trade in ladies’ hats. Certain elements of the chapeau might be made of papier-mâché, metal, or fabric, but actual birds’ feathers were deemed a necessity. For centuries, royalty had worn sprays of feathers on bejeweled tiara-like aigrettes and other headwear that signified aristocracy. Gilded Age Americans now sought to reenact “London in the time of Charles I or in Versailles in the time of the Louises,” according to one New York Episcopalian bishop of the era. The “veritable pageant of wealth” mandated the “enormous flopping feather hats assorted to every costume,” claimed Elizabeth Drexel Lehr, one of the Astor Four Hundred. Men were also susceptible to the fad, as feather trimmings on men’s hats became popular. The middle classes, copying the elite, also demanded plumage and feathers. The Sears, Roebuck catalogue of 1897 promoted women’s hats, including “The Evette” and “The Susanne,” with more modest plumage. All ladies might be alert to the jeopardy of the plumed chapeau. Attending a soirée, Mrs. Goodhue Livingston dipped her head too close to a flaming candle, whereupon her “ostrich plume caught fire.” There was “a great to-do until a gallant gentleman clapped it between his hands.”

The fashionable feathers meant a financial bonanza in the later 1800s for hunters, who amassed and sold these sought-after insignia in the burgeoning plume trade. Whole stuffed birds, such as doves, were used as decorative ornaments. “There were no birds around in the streets except sparrows in winter, but ladies’ hats more than made up for it,” recalled young Clarence Day Jr., who grew up in the city. He “had never seen a blue jay in the open, or a bobwhite or a swallow, but saw plenty of them on ladies.” Ogling the remarkable chapeau of an afternoon teatime visitor to the family home near Madison Square, the boy eyed the visitor’s crown with its “large bird with prominent eyes, and a red ruby breast like a robin’s. His long wings stood stiffly out,” he recalled, “and his attitude was that of flight—he looked as though he was about to swoop at the carpet and snatch up a fish.”

In one two-day survey in 1886, the American Museum of Natural History ornithologist Frank Chapman walked the streets of New York City, where he identified the wings, feathers, heads, and entire bodies of 174 birds representing 40 different species (especially the tern, the cedar waxwing, and the bobwhite) adorning ladies’ hats. In rookeries or while feeding along migratory routes, entire flocks—herons, flamingoes, roseate spoonbills, and numerous others—succumbed by the thousands. In 1886, some five million birds were estimated to have been killed, dismembered, and plucked for their feathers.

As entire species of birds became casualties of women’s fashion on both sides of the Atlantic, the backlash was severe. In the United Kingdom, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds launched an antiplume campaign, as did the Audubon Society in America, hosting public lectures with titles such as “Woman as Bird Enemy.” By the early 1900s, the fad for feathers waned under social pressures, and by World War I, the “age of extinction” of these birds came to an end.

Color Harmony

Strict rules for color combinations governed Gilded Age attire. Beyond a flattering palette in clothing lurked a regimen that distinguished good taste from bad, refinement from vulgarity. Manners, Culture and Dress warned, “It is of importance . . . that you do not overstep the boundaries of good taste in the number and variety of colors which you may employ. You may display the greatest taste and judgment in the contrast and harmony of color, and yet, owing to their profusion, they may obtrude themselves glaringly to the eye, . . . an error that ought to be carefully avoided.” A discussion of “harmony of color in dress” in Manners establishes all “the canons of the laws of harmony” and provides over one hundred of the “most agreeable” harmonious combinations for reference. They include

- Blue and lilac

- Blue, orange, and black

- Scarlet and slate

- Crimson and orange

- Crimson and maize

- Blue and salmon-color

- Yellow, purple, and crimson

- Green, scarlet, and blue

- Orange, blue, scarlet, and claret

Scores of other combinations in Manners guaranteed flawless color coding from head to toe, through every season, and daily from dawn to nightfall.

For All Occasions

The maxim “The dress should always be adapted to the occasion” applied to the Gilded Age as to the present day—perhaps more so, for every hour of the day, every location, every occasion of the Four Hundred and their devotees demanded clearly defined apparel. Etiquette guides such as Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society showed the way according to the following rules:

- Evening Dress: Means full dress. . . . It will serve for dinner, opera, evening-party, everything but the ball.

- Morning-dress for Home: May be more simple than for visiting, or for hotel or boarding-house.

- Morning-dress for Visitor: A dress with a closely-fitting waist should be worn.

- Morning-dress for Street: Should be plain in color and make, and of serviceable material. The dress should be short enough to clear the ground.

- Business Woman’s Dress: It should be made with special reference to easy locomotion and to the free use of the hands and arms.

- The Promenade: Admits of greater richness in material and variety in trimming. . . . It should . . . display no two incongruous colors.

- Carriage-dress: Silks, velvets and laces are all appropriate, with rich jewelry and costly furs.

- Riding-dress: There is no place where a woman appears to better advantage than upon horseback. . . . Her habit should fit perfectly without being tight. The skirt should be . . . long enough to cover the feet, while it is best to omit the extreme length, which subjects the dress to mud-spatterings and may prove a serious entanglement in case of accident.

- Dress for Receiving Calls: Her dress may be of silk or other goods suitable to the season or to her position, but must be of plain colors.

- Dress of Hostess: The hostess’ dress should be of rich material, but subdued in tone, in order that she may not eclipse any of her guests.

- Dinner-dress: We do not in this country, as in England, expose the neck and arms at a dinner party. These should be covered.

- Dress of Guests at Dinner-party: All the light neutral tints and black, purple, dark green, garnet, dark blue, brown and fawn are suited for dinner dress. But whatever color the dress may be, it is best to try its effect by gaslight and daylight both, since a color which will look well in daylight may look extremely ugly in gaslight.

- Dress for Evening Call: A hood should not be worn unless it is intended to remove it during the call.

- The Soiree and Ball: These occasions call for the richest dress. . . . The richest velvets, the brightest and most delicate tints in silks, the most expensive laces, low neck and short sleeves, elaborate head-dress, the greatest display of gems, flowers, etc., all belong to these occasions.

- Dress for the Theatre: The ordinary promenade-dress is suitable for the theatre, with the addition of a handsome shawl or cloak. . . . In some cities it is customary to remove the bonnet in the theatre—a custom which is sanctioned . . . and a consideration of those who sit behind.

- Dress for Lecture and Concert: . . . Silk is the most appropriate material for the dress, and should be worn with lace collar and cuffs and jewelry. . . . The handkerchief should be fine and delicate; the fan of a color to harmonize with the dress.

- Dress for the Opera: The opera calls out the richest of all dresses. A lady goes to the opera not only to see but to be seen, and her dress must be adopted with a full realization of the thousand gaslights which will bring out its merits or defects. . . . A most important adjunct to the opera-costume is the cloak or wrap. This may be of white or of some brilliant color. Scarlet and gold, white and gold, green and gold or Roman stripe are all very effective when worn with appropriate dresses.

- Wedding-outfit: A bride in full bridal costume should be dressed entirely in white from head to foot.

- The wedding-dress: The dress may be of silk, brocade, satin, lace, merino, alpaca, crape, lawn or muslin. The veil may be of lace, tulle or illusions, but it must be long and full. It may or may not fall over the face. . . . No jewelry should be worn save pearls or diamonds.

- Dress of Bridegroom: The bridegroom should wear a black or dark-blue dress coat, light pantaloons, vest and necktie, and white kid gloves.

- Dress of Guests at Wedding-reception: The guests at an evening reception should appear in full evening-dress. No one should attend in black or wear mourning. Those in mourning should lay aside black for gray or lavender.

One caveat in dressing for the Gilded Age: “Never dress above your station; it is a grievous mistake, and leads to great evils, besides being the proof of an utter want of taste.”