Well Behaved

Ward McAllister, Autocrat of Conduct

The grand master of branding in Gilded Age New York, Samuel Ward McAllister (1827–1895), coined the term “the Four Hundred,” ever afterward representing Society at its most numerically exclusive. The Four Hundred marked those who were in and, by omission, those exiled to the social nether regions. Friends and foes alike created sobriquets for McAllister, from the heiress Elizabeth Lehr’s fond “Shepherd of the ‘Four Hundred’” to the Knickerbocker New Yorker Stuyvesant Fish’s dismissive “demagogue.” For certain, McAllister earned his reputation as the kingpin of New York—and Newport—Society of the late 1800s.

McAllister was the son of a hospitable but impecunious Savannah attorney—“Wardy” to his mother—who gave his family cool summers in Newport, Rhode Island, the summer destination of numerous southern families who, since the 1700s annually boarded vessels in Savannah or Charleston or Wilmington. Wealthy planters built fine summer homes, while others lodged at farmsteads, as did the McAllister family. Ward recalled boyhood summers flying kites and building bonfires at the seaside. And it was a godsend to escape the torrid southern heat. In those days, McAllister observed, Newport was “a Southern colony.”

Later, McAllister caromed from one region of the country to the other. As a young man, he ingratiated himself to a wealthy New York spinster aunt who left him a mere thousand dollars in her will (all of which he spent on evening dress for a ball given by Mrs. John C. Stevens, whose husband was the first commodore of the New York Yacht Club). Returning to Savannah, Ward studied law and, with his cousin Sam, sped to San Francisco in 1850 to join the senior McAllister’s new law office in the heady Gold Rush days of the California forty-niners. The legal work was lucrative, though San Francisco’s raucous, ribald “Barbary Coast” was repellent to a young man who already considered himself a connoisseur of fine things and claimed French ancestry and elite family ties. (His father’s favorite maxim was “Be sure, my boy, that you always invite nice people.”)

By 1852, McAllister had married the bashful, reclusive Sarah Taintor Gibbons, an heiress whose social connections and wealth furthered his goal of social distinction. Their European wedding journey, recounted in McAllister’s memoir, catalogues dinners and balls spent in the company of an array of aristocrats, government ministers, high-ranking military officers, and “young Italian swells.” Rome, he found, was “full of the crème de la crème of New York Society.” The wedding sojourn was also McAllister’s apprenticeship in fine foods and wines. The Bordeaux caves harbored a vintner’s perfection, and McAllister declared that in southern France he “learned how to give dinners” and in Germany gave “one to two dinners a week.”

Briefly back in the Savannah in 1858, McAllister within a year had bought his own farm, known as “Bayside,” in Newport, which became its own story of the Gilded Age, but McAllister’s engineering of the New York social machine is a tale to tell. His proclamation of the Four Hundred echoes in the twenty-first century, but largely forgotten is another term he coined to refer to the pillars of Society: The Patriarchs. Establishing a beachhead in New York with the purchase of a rather modest house at 10 West Thirty-Sixth Street, the socially ambitious McAllister set to work with a scheme that harked to his pre–Civil War days. Originating in London and European cities, social dances called assemblies had flourished from the 1700s in colonial America well into the 1800s. The Philadelphia Assembly and the New York Dancing Assembly proceeded in tandem, while smaller assemblies gathered in Norfolk, Williamsburg, Richmond, and other southern locales. Particular dances won and lost favor, including the quadrille, mazurka, polka, and two-step, but assemblies were largely occasions for the elite of each city to gather, socialize, and reaffirm their own social positions.

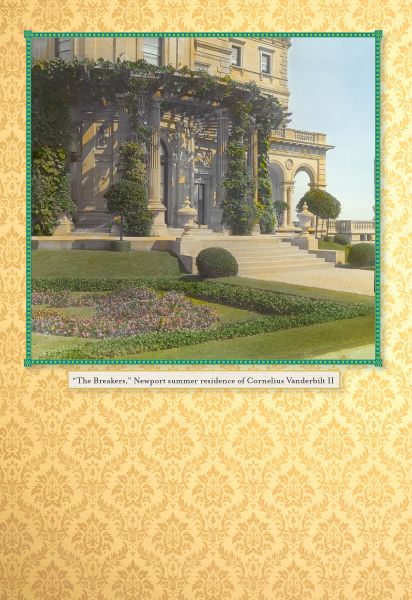

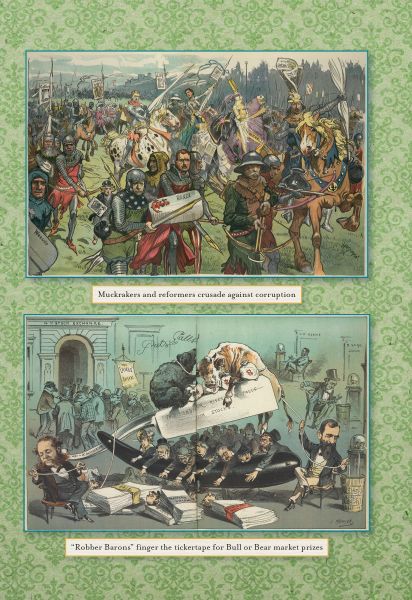

The assemblies languished in the post–Civil War years, but the format of these gatherings intrigued McAllister, who in 1866–67 hosted cotillion suppers at Delmonico’s, where prominent women were seated at the head of the table and encouraged to confide their views about the fluctuating New York social scene. Such women, McAllister knew, had at their “finger’s ends the history of past, present, and future, . . . critical, scandalous, with keen and ready wit.” The former “Knickerbockerocracy” was tremulous before the onslaught of new wealth amassed from the railroads, from mining, manufacture, and finance. Old and new money were jostling for position.

With a reverential devotion to European aristocracy, McAllister would have empathized with the quest of the nouveau riche for improving their familial lineage. Tiffany wisely added a department for the “blazoning” of custom heraldry, wherein the customer could combine elements of ancient English coats of arms from the escutcheons of several dukes or lords. Half a shield here, a sword or lance there, winning colors, a Latin motto, and the order was placed. Concluded the socialite Elizabeth Lehr, “The results were decidedly original and quite unknown, but the owners were delighted.”

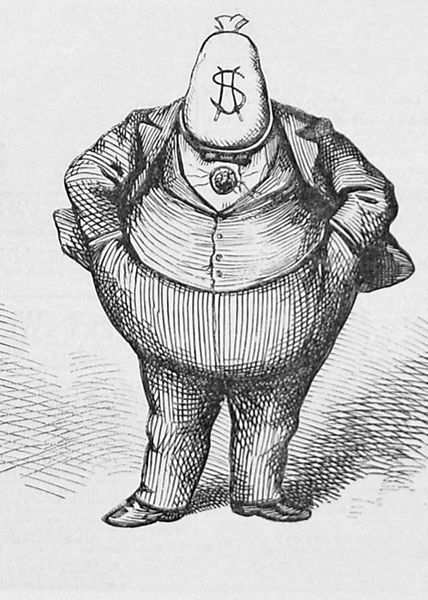

When McAllister came to the fore in 1872–73, his timing was exquisite. The flagrantly corrupt era of New York’s William Marcy (“Boss”) Tweed had finally closed with Tweed’s downfall in 1871–72. His notoriety had disgraced the city and made the Irish “Tweed” and his immigrant minions and victims appalling signifiers of New York. Tweed’s Tammany Hall was synonymous for greed, corruption, and a low-life prevalence of saloons and coarse amusements. New York’s most infamous figure was nationally represented in politically scathing cartoons.

In the wake of the scandal, Ward McAllister offered New York society a way to redeem itself with a new social framework of his own design: The Patriarchs. With a membership limited to twenty-five gentlemen identified by (and including) McAllister, the Patriarchs would redefine New York Society, representing the city’s cultural and social values at their irreproachable best. The twenty-five were bound by their honor to uphold the highest standards of rectitude in the city and beyond (and any financial ties to the Tweed era disregarded). The twenty-five names on the list, the summa of New York’s aristocracy, combined old and new money, the convergence itself McAllister’s signature achievement:

- John Jacob Astor

- Edwin A. Post

- William Astor

- A. Gracie King

- DeLancey Kane

- Lewis M. Rutherford

- Ward McAllister

- Robert G. Remsen

- George Henry Warren

- William C. Schermerhorn

- Eugene A. Livingston

- Francis R. Rives

- William Butler Duncan

- Maturin Livingston

- E. Templeton Snelling

- Alexander Van Rensselaer

- Lewis Colford Jones

- Walter Langdon

- John W. Hamersley

- F. G. D’Hauteville

- Benjamin S. Welles

- G. G. Goodhue

- Frederick Sheldon

- William R. Travers

- Royal Phelps

The genius of the Patriarchs (the twenty-five later expanded to fifty) was its self-policing and self-perpetuation. Members elected successors, and the membership functioned like a private company whose stock is held solely by owners. Should one Patriarch commit a misstep, his colleagues would let it be known among themselves that a transgression had occurred and take steps to rectify the problem by counseling their offending brother-in-wealth. For example, suppose a Patriarch were temporarily short of cash and rented his private box in the exclusive Golden Horse-shoe at the Metropolitan Opera House to “a family of rank outsiders . . . who weaken Society by sapping the vigor of its exclusiveness,” as Ralph Pulitzer noted in New York Society on Parade (1910). The owner of the box would be invited to have a word with a fellow Patriarch, perhaps at his club, and urged to cease and desist.

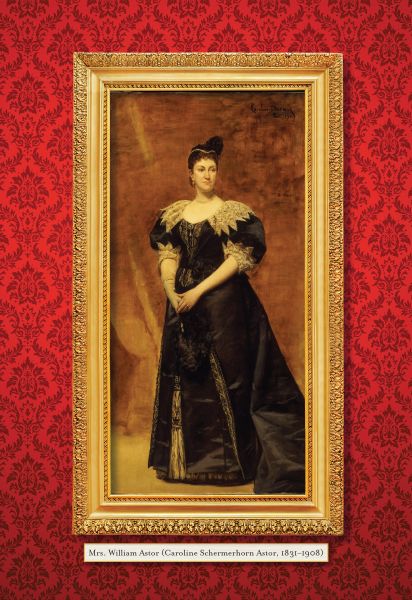

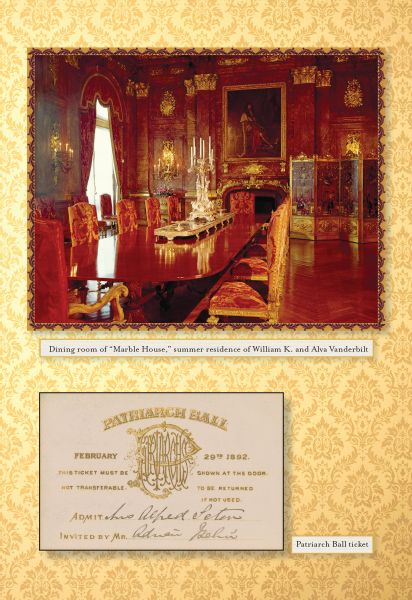

McAllister’s efforts at social engineering culminated with one crucial masterstroke: he invited Caroline Astor to become a special adviser to the Patriarchs. The rest, so to speak, is history, as Mrs. Astor launched her unprecedented reign over Gilded Age Society, an era of unprecedented opulence. She attended the exclusive annual Patriarch Ball and soon adopted Ward McAllister as her chamberlain.

The idea of the Four Hundred notables widely took hold when McAllister quipped to a Tribune reporter on March 25, 1888, “Why, there are only about 400 people in fashionable New York Society. If you go outside that number you strike people who are either not at ease in a ballroom or else make other people not at ease. See the point?” McAllister coyly refused to list the Four Hundred until Mrs. Astor’s ball of February 1, 1892, when he produced a listing of just over three hundred names, claiming that others were abroad. One doyenne of Old New York, May Rensselaer, recalled McAllister as “the czar whose dictates were law to Society” but who wisely asserted his “power behind the throne of social preeminence.” “He sought for some one worthy of his counsel and direction,” she continued, “and found her in Mrs. William Astor, a woman of gracious manner and unquestioned standing.” One critic demurred, calling their public partnership “a traffic in social positions.”

McAllister outlived his reputation as the arbiter of manners and mores of Gilded Age Society. A few remembered him as the deservedly successful arbiter elegantiarum of his era, as Maud Howe Elliott phrased in Latinate tribute. In time, however, his mannerisms lent themselves to satire (sentences ending with the studied pseudo-British nonchalance of “dontchersee?” or “dontcherknow?”), and his publication in 1890 of his late-career memoir, Society as I Have Found It, infuriated the very Society he had shaped, cultivated, and served. The memoir struck the Four Hundred as an egregious breach of confidentiality or, worse, a how-to manual for social climbers. Society did not care to see itself reflected in such a faulty mirror, and McAllister’s book had exposed him as an exalted Gilded Age butler. By this time, he and Mrs. Astor had long parted ways; there was no need for her to cancel her dinner party to attend his funeral on February 5, 1895.

How to Navigate a Public Encounter

The ladies and gentlemen who braved Gilded Age Gotham’s streets and avenues braced for sensory overload. The sidewalks around their homes on Madison Square or Fifth Avenue might be peaceful at certain points of the day, but elsewhere the city was a hive of construction and commerce. Odors of acrid coal smoke, drizzling soot, and the screech of the El trains as they stopped and started along Sixth Avenue assaulted the ears, eyes, and nostrils. Roadways rang with voices, clanging bells, and hooves scraping and clattering on the pavement. Cabmen called out, “Take you all around—see everything—for a dollar,” while teams of heavy draft horses pulled wagonloads of cargo from milk to coal, beer to bricks. (In 1900, New York City averaged just under five hundred horses per square mile.)

From the 1890s on, motorcars mixed with horse-drawn vehicles, their noisy engines spewing fumes, their Klaxons blaring warnings to all. The mayoral campaign of 1903 highlighted the myriad nuisances. The new Fusion Party, which sought to oust the corrupt Tammany political machine from office, promised to repair “asphalt pavements found in very poor order,” to remove snow from the streets in a timely fashion, to rid the streets of rubbish, and to attend to “the vexatious problems of street traffic.” Danger lurked around every corner, the Herald reported, citing the threats of loitering “roughs” and “loafers” and alarming readers with accounts of smashed carriages and runaway horses. At every curb, mounds of ripe horse manure awaited the misstep of the custom-fitted boot or shoe.

Figure 20. Fifth Avenue between Forty-Fifth and Forty-Seventh Streets, 1905

The rules and regulations for conduct on the street were set by this urban reality, and gender played its part, with gentlemen cast as protectors and ladies as damsels in need of assistance. This was no simple reprise of the legend of Sir Walter Raleigh sparing Queen Elizabeth from the mud puddle by gallantly spreading his cloak over the turbid pool. Such chivalric lineage was doubtless pleasing, but milady on the sidewalks of the Gilded Age was in need of help largely because the iron grip of fashion and propriety hemmed her in, from her plumed headdress to her buttoned boot. This woman was held in bondage by her own clothing.

The Gilded Age chronicler Clarence Day Jr. tallied the feminine vexations on the city street. From boyhood, he recalled that “ladies were elaborately dressed in long, trailing skirts, and whenever they walked in the street, they had to hold up these skirts with one hand.” “They had to do this gracefully,” Day continued, “and at just the right height, so as not to reveal too much of their ankles, and yet keep the hem free from dirt.” With one hand occupied with the skirt, the other “carried an umbrella or parasol, or on cold days a muff.” Hair styles and hats also proved treacherous. “Ladies’ hats were perched up on top of their hair, and although they were pinned on with long jeweled pins, they were insecure in a wind, and their hair was skewered with quantities of hair-pins.” “No matter how thoroughly ladies were buttoned up,” Day concluded, “they were always coming apart.” (The hair- and hat pins, he might have added, were known to be weaponized when a lady felt unduly encroached on.)

The ladies’ transactions were limited in public, even in the daytime. Chances were, they lunched at the homes of friends or, on occasion, at public lunchrooms in the department stores where they shopped, especially in the area known as “Ladies’ Mile” that featured such quality establishments as Lord & Taylor. They instructed that store clerks send the larger items to their homes and the bills to their husbands, fathers, uncles, or older brothers. But they carried small parcels from the stores, perhaps a box of chocolates or a tin of fine tea. “In the side seam of their skirts was a pocket,” Day revealed, where they secreted such useful items as “a tiny purse, a handkerchief, and a silver-topped vial of smelling-salts to use if they felt faint.” Since “this pocket was not easy to get at,” he noted, “and it was embarrassing to feel around for it,” the ladies had a trick up their sleeves. “When women got on a street-car, they tucked a nickel inside their buttoned gloves.”

Men were expected to assist a lady during her outings. “Street Etiquette” suggested that “where a gentleman can render aid, he kindly gives it.” “A gentleman, whether walking with two ladies or one,” commanded Emily Post, “takes the curb side of the pavement.” “In thoroughfares where persons are constantly passing,” advised Sensible Etiquette, “gentlemen keep to the left of the lady . . . to protect her from the jostling elbows of the unmannerly.” American Etiquette and Rules of Politeness (1882) underscored the point: “A gentleman walking with a lady” must give her the side “on which she will be least exposed to crowding.” “All conductors were supposed to lend a hand to help ladies get on and off” the streetcar, Day noted. “Under no circumstances,” however, warned Emily Post, “should a gentleman take her arm, or grasp her by or above the elbow, or shove her here and there, unless, of course, to save her from being run over.”

These guides promoted a studied politeness. The gentleman escort carried out his duties “swelling with whiskers and grandeur,” while “the really well-bred man always politely and respectfully bows to every lady he knows.” The “true gentleman” and “true lady”—versus the “boorish person”—“are always kind and courteous to all they meet.” Drawing-room “sunshine,” one insisted, must extend “to the streets, in public conveyances, amid the jostling crowd, beneath the fret and care of work.” This blandishment covered a nest of specific behaviors to be followed religiously or avoided at all costs. On the street or elsewhere in public, the key Gilded Age guideline was constraint of the body and voice, even amid the maelstrom of traffic. Circumstances varied, acknowledged the guides, thus prompting a certain ambiguity. “If her smiles are faint and her bows are reserved,” explained Social Etiquette of New York (1879), they were nonetheless “not discourteous.” Gentlemen took their cues as best they could, bowing slightly and lifting their hats or touching the brim.

Class itself was a major determinant of street conduct, as was one’s station in life. A gentleman walking by himself “should give the preferred part of the walk to a lady, to a superior in age or station, or to a person carrying a burden.” Yet appearances might deceive. Emily Post’s Etiquette cautioned that a well-dressed “show girl” might pass herself off as a lady. Uncertain of her status, a gentleman was advised to “suppose that an apparent lady is a lady.” Under the gaslight of the evening, what is more, the facial features of a lady acquaintance might appear sufficiently altered to make her a stranger. It was best to bow and greet her in good faith. “An inferior should on no pretense,” however, “detain a superior.”

A chance encounter on a public street provided an opportunity for conversation. Gentlemen wishing to stop and converse together on the street could do so, “provided they retire to the side of the walk.” It was at a lady’s discretion “whether she shall stop to speak.” A gentleman must ask permission to have a conversation, and if permitted, he must fall into step with her. In any case, conversation in mixed company while standing on the pavement was taboo. If the lady strikes up a street conversation with a gentleman (an acquaintance or family member, never a stranger), he “does not allow her to stand while talking with him, but offers to walk with her.” However, “he is not obliged to walk her home” and “can take his leave without making any apology,” albeit with the obligatory “bow and a lift of the hat.”

The etiquette guides bristled with warnings against violations that lay like traps on the city’s streets. Emily Post censured “loud talking” and being “conspicuous.” Sensible Etiquette warned that “snuffling, hawking, expectorating must never be performed in society.” American Etiquette sounded a cautionary note: “Do not try to ‘show yourself off’ upon the streets. . . . The true lady walks the streets unostentatiously and with becoming reserve.” She “never forms acquaintances of gentlemen on streets, nor does she . . . court their attention.” A practiced obliviousness serves her well: “She appears unconscious of all sights and sounds which a lady ought not to perceive.” It need hardly be noted that a young lady must avoid the streets after sundown. And a lady who impulsively dashes across the street in front of a carriage both endangers herself and appears “inelegant.”

Specific prohibitions for men on public streets served as a counterpoint to the ladies’ caveats. They included “a peculiar and affected gait,” “swinging of the cane,” “cocking of the head to one side,” “holding cigar in affected manner,” and wearing the hat cockeyed (“on one ear”). No gentleman was entitled to stand in public places “offensively gazing at ladies as they passed.” Nor should he smoke while walking with a lady. When he meets an acquaintance on the street, no questions should be asked about where the individual has been, where he or she was going, or the contents of any package being carried. “Prying curiosity is indelicate, even if the victim is your closest friend.” A boorish man who importunes a young lady warrants the treatment he gets when she “cuts” him, finding it “necessary to use severe means to rid herself of a troublesome would-be gentleman.”

A knotty problem arose when a gentleman recognized a lady acquaintance on the sidewalk of a New York street while driving, say, a phaeton, holding a whip and gripping the reins to restrain his “restive beasts.” To “shift his whip and reins, and lift his hat” to greet her required dexterity that few could claim. Gentlemen solved this problem by touching the butt of the whip to the brim of the hat to acknowledge acquaintance. “A wellbred foreigner would never dream of saluting a lady by raising his whip to his hat,” lamented the author of Sensible Etiquette, but Gilded Age New York happily endorsed the custom.

Retail sales floors were as public as the streets and thus a worthy topic for the etiquette guides. Consideration for the sales staff and fellow shoppers was paramount. “Do not endlessly consume the time of the clerk and keep other customers waiting,” advised American Etiquette. “It is exceedingly rude to the salesman to sneer at or depreciate his wares. . . . Never give insult by offensively suggesting that you can do better elsewhere.” If the shopper recognized a friend or acquaintance in the middle of a transaction, she was cautioned not to interfere. (“It is uncivil to interrupt them in any manner while they are making their purchases.”) Above all, “do not volunteer your criticism either upon their taste or upon the goods.” A customer should say “please” to the sales clerk and refrain from bargaining about price. If she became dissatisfied with cost, style, or quality, the solution was clear: “simply retire.”

If quiet decorum was the norm, however, Post’s Etiquette nonetheless offered two venues that provided outlets for vociferous expression: “at outdoor games, or at the circus.” In either one, “it is not necessary to stop talking. In fact, a good deal of noise is not out of the way in ‘rooting’ at a match.” “A circus band,” she noted, “does not demand silence in order to appreciate its cheerful blare.” Thus, the well-behaved ladies and gentlemen were free at last to raise their own voices, but solely in the sports stadium or under the circus tent.

Correspondence

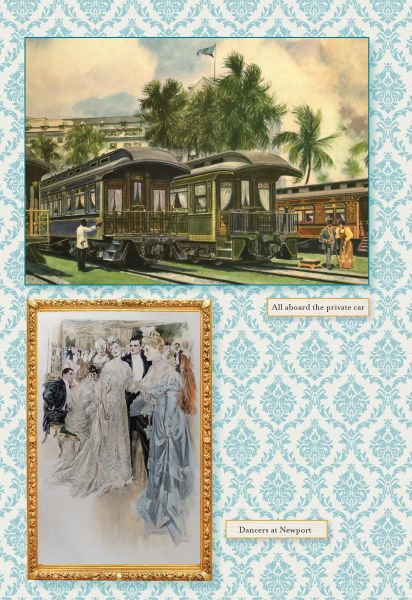

When the morning mail arrived on silver breakfast trays at the bedsides of Gilded Age New Yorkers of the Four Hundred, expectations ran high, whether in the city, in Newport, or at a country house. The coffee, tea, and toast were routine, but the letters brought with them the hint of promise. Breath held, the lady of the house shuffled the envelopes in search of those addressed in distinct “delicate handwriting, embellished with Gothic scrolls, which no one dreamed of imitating.” These were assuredly “invitations of importance,” and if the winter season was under way, one such envelope might contain the most highly prized invitation of all. This most “coveted slip of cardboard” was an invitation to Mrs. Astor’s late-January annual ball.

Handwritten correspondence covered every conceivable purpose in the Gilded Age, from legal documents to wedding invitations. The typewriter was in its infancy, and telephones were reserved for business calls until the 1910s (even then frowned on for social uses). Telegrams were out of the question except for urgent messages notifying faraway recipients of critical matters, such as health crises. Well-to-do New Yorkers might dispatch letters by messenger, as does Edith Wharton’s young gentleman in her novel The Age of Innocence, writing “a line” to a visiting countess and dispatching it “by a messenger-boy.” Otherwise, the efficient US Post Office was ready to deliver handwritten letters promptly with a first-class two-cent stamp bearing the engraved portrait of George Washington.

Etiquette manuals spoke sternly on the topic of correspondence. “Letter writing, practically considered, is the most important of all kinds of composition,” insisted the popular American Etiquette. Its author, Walter Raleigh Houghton, underscored his point: “By letter writing,” he wrote, “much can be done to maintain and strengthen our social ties.” The very word “letters” referred to the mail but also to the handwriting that was widely believed to reveal the essence of an individual life. “The culture of a person is plainly indicated by his letters,” Houghton admonished. One’s worthiness as a human being was expressed in the very curve of the letters, caste and class evident in the formation of the p’s and q’s.

Penmanship was thus a most serious study from childhood. Whether tutored at home or enrolled in school, a child spent untold hours “training the hand” by practicing the loops and swerves of proper cursive penmanship. Tutored in childhood in “private classes” in the home of the New York financier J. Pierpont Morgan, Daisy Hurst felt “drilled in penmanship as soldiers drilled in marching.”

Most children spent months bearing down with lead pencils on practice sheets before advancing to pens with points that were dipped in ink wells and applied at last to quality paper. Those born before the Civil War followed a curriculum devised by H. C. (Henry Caleb) Spencer, whose Spencerian Key to Practical Penmanship set the standard for cursive writing from the earlier 1800s to the post–Civil War years. Younger ladies and gentlemen were schooled in a method devised by A. N. (Austin Norman) Palmer, whose Palmer Method promised “easy and legible handwriting.” The importance of penmanship could not be overstated, as Houghton warned: “It is as great a violation of propriety to send an awkward and badly written letter, as it is to appear in the company of . . . people with swaggering gait . . . and unkempt hair.” (Emily Post added “broken shoe laces.”)

The handwriting of Gilded Age social secretaries met the standards of the Spencer or Palmer regimens, and a few exceeded them. For marquee events such as weddings or evening balls—including Mrs. Astor’s—the “invitations of importance” were penned by a somewhat mysterious woman claiming Incan royal ancestry. Maria de Baril “acted as a sort of social secretary to all the great hostesses of New York and Newport.” Miss de Baril was no mercenary. According to Elizabeth Lehr, who sent and received the scribe’s efforts on many occasions, Miss de Baril made certain “that invitations issuing from her pen would only be received by people of eminence before she would dispatch them, . . . perfectly worded to suit the occasion.” Her inimitable style was her trademark, as was her “weird assortment of bead necklaces and amulets.” (It was noted that Miss de Baril worked from her own residence, her resemblance to a gypsy unobserved by the households of those who retained her services.)

More respectably clad social secretaries of the era had also been subjected to Spencer or Palmer in their primary school years, and their penmanship was in demand. Ladies of the Four Hundred routinely delegated their many missives to women employees (just as clerks penned business documents at the behest of employers in town). In Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, the protagonist, Lily Bart, finds herself pressed into such service. At a house party outside the city, she learns that her hostess’s secretary has been “called away,” leaving “notes and dinner-cards to write, lost addresses to hunt up, and other social drudgery to perform.” Would Lily please lend a hand? An impecunious single young woman, she is beholden to those who host her. Seating herself at the elegant “slender writing table,” Lily barely masks her irritation.

Figure 21. At the writing desk

Social strictures extended to the paper and ink as well. Stationery was marketed in colors, but proper etiquette mandated the one-and-only white. “For any kind of letter no color is more tasteful than white, and gentlemen should use it exclusively.” Lined (ruled) paper “may be used without violating good taste,” but “unruled paper is preferable because it is more stylish.” Further, “a social letter ought to be written on a whole sheet of paper,” though a half sheet was passable for business. “Avoid monograms, floral decorations and landscapes,” one etiquette manual advised, pronouncing them “cheap” and “decidedly in bad taste.” As for ink, black was preferable to “fancy” inks.

The content of a letter was vitally important, though perils lurked. “Good grammar, correct orthography, precise punctuation will not make a clever communication, if the life and spirit of the expression are wanting,” warned Richard A. Wells in Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society. He advised letter writing as an exercise in mental conversation, which Emily Post called “simplicity, naturalness, and force.” He offered encouragement: almost any person of ordinary intelligence can learn to express him- or herself in an acceptable manner on paper. Wells kindly provided a model:

127 Lee Ave. Troy, N. Y.

My Dear Friend,

Your good letter came in due time, and I hasten to reply, as my husband and myself are about to leave the city for a short Eastern trip. We shall spend a few days in Boston and while there we anticipate the pleasure of calling upon our mutual friend, Agnes Eaton. We expect to return some time in May and trust we shall meet your family later at our summer house in Stamford. I am, with regards to all,

Sincerely your friend,

Ursula M. Dickinson

Ward McAllister, too, provided helpful models for the acceptance and decline of social occasions, as well as those for invitations:

16 West 86th Street

Dear Mr. Murray:

It will give me great pleasure to dine with you on Friday next, April 12th, at eight o’clock.

Yours truly,

J. J. Murray

Fair View,

Newport, R. I.

Mrs. Marcy regrets that as she is leaving Newport on Monday, she is unable to accept Mr. and Mrs. Clinch’s kind invitation for the 16th.

Edith Wharton saw the quandary of letter writing as her opportunity to turn a social breach into sharp satire in best-selling fiction. In The Custom of the Country, her protagonist, a social-climbing midwestern young woman, spends the winter season in a New York hotel with her parents. Her social goal, Fifth Avenue, is literally in sight of the hotel suite, but the route to it, a complete mystery, for she and her parents are ignorant of Society’s rules. When a dinner invitation arrives by mail from a lady of an Old New York family, the young woman assumes the task of replying in her mother’s name. Tempted to use her silver-monogrammed “pigeon-blood note-paper with white ink,” she hesitates, suspecting that the white paper of the invitation is the newest fashion (“What if white paper were really newer than pigeon-blood? It might be more stylish.”) Her quandary deepens as she faces dilemmas of phrasing (“take dinner” or simply “dine”?) and the correct signature of her mother (first name only? Mrs.?). Her reply, on hotel stationery, signals that her mother is a divorcée, and the hotel letterhead is a striking violation of decorum. The compounded errors are humorous to those in the know, but Wharton’s scene flashes warnings that correspondence is treacherous.

Cards, Visits, and Calls

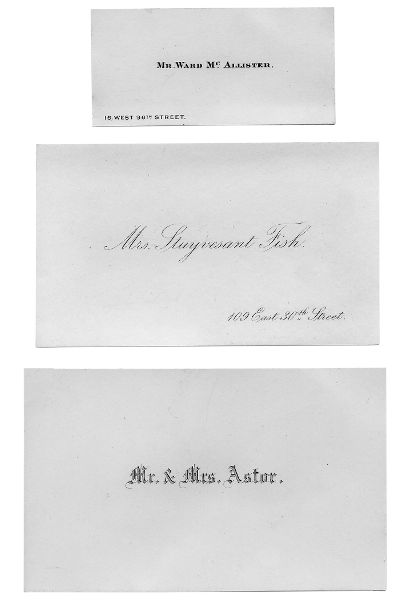

According to all the guides, irreproachable Gilded Age etiquette required calling cards for ladies, gentlemen, and even children, engraved with the individual’s name and address—unless the person was Mr. or Mrs. Astor, in which case the address was superfluous.

A holdover from the Victorian era, the cards were a social necessity, presented to announce visits or social calls, which were “brief, and often quite formal,” according to American Etiquette. In bustling New York City, twenty-minute calls largely replaced the longer visits of the past, but the protocol was fixed. Warned American Etiquette, “Everyone should, as far as possible, attend to his or her duties in this direction.” Emily Post stated the purpose: to provide “evidence of one person’s presence at the home of another.” Explained another guide, “The formal call is a mere device for keeping up acquaintance.”

The token of acquaintance, the card itself, was nearly regulation size. Emily Post gave the dimensions according to gender (for ladies, about three inches wide, two and a half high, while gentlemen’s cards were a bit longer and narrower). These small rectangles of “unglazed bristol board may be of medium thickness, or thin, as one fancies.” Etiquette of Visiting Cards (1880) urged avoidance of “anything like ‘pearl-cards,’ ‘snow-flake,’ pictorial and other innovations designed to attract attention to the card itself.” “Gilt-edged cards,” it added, “are quite passé.”

The engraving, “always in good form,” was to be in script, plain block lettering, or old English (preferred by Mr. and Mrs. Astor). Said Post’s Etiquette, “All people who live in cities should have the address in the lower right corner.” As for carrying the cards, “Gentlemen ought simply to put their cards into their pockets.” For ladies, “a small, elegant portfolio called a card-case” was to be held in hand, perhaps “with an elegant handkerchief of embroidered cambric” to give “an air of good taste.” (A code developed for bending the corners of cards: for an in-person visit, bend the upper right corner; for congratulations, the upper left. A lower-left bend meant a condolence visit, and a person leaving for a long trip could be announced by a bend of the lower right corner. (“In bending or turning the card,” warned Etiquette of Visiting Cards, “care should be taken not to break the surface.” Also crucial: “Ladies do not leave cards upon gentlemen.”)

The ritual of personal calls involved “a system of strict formality” within “complicated . . . social machinery,” observed American Etiquette. It was understood that gentlemen would be occupied with business, leaving the ladies to rounds of social visits. Instructed Manners, Culture and Dress, “If the call is made in a carriage, the servant will ask if the lady that you wish to see is at home. If persons go on foot, they go themselves to ask the servants.” The savvy maid or butler, expecting the caller, took hold of the silver card tray in the left hand and prepared to open the door. (Warned Post’s Etiquette, “A servant at the door must never take the card in his or her fingers.”)

Card presented, the caller waits while the maid or butler withdraws, returning to admit the caller into the home (“This way, please”) or to regrettably inform the caller that the lady or gentleman of the house is “not at home,” often a polite phrase meaning “not at home to visitors” (or, at the extreme, “not at home to you”). American Etiquette noted that “calls of pure ceremony are sometimes made by simply handing in a card,” which surely relieved countless ladies from tiresome social chores. Some of the cards were “p.p.c.’s,” an abbreviation for the French pour prendre congé (taking leave), meaning that the visitor did not have time to bid adieu before departing, with the abbreviation often translated as “present parting compliments.”

Two sorts of calls, however, necessitated a visit: of condolence or congratulation. “These cases demand the leaving of cards in person,” advised The Well-Bred Girl in Society (1898). Some ladies appointed special days for receiving callers, while American Etiquette sniffed, “Most persons who are well bred will endeavor to receive callers whenever they come.” It was “bad taste” for the householder to tuck the received cards around the frame of a hallway mirror. (“Such an exposure shows you wish to make a display of the names of visitors” and announces “ill-regulated self-esteem.”) Nonetheless one guest recalled the great silver salver in Mrs. Astor’s front entrance hall “flowing over with visiting-cards, some turned over at the corners, many with messages of gratitude for operas heard, of banquets eaten.”

On the first of January, from ten a.m. until nine p.m., with businesses on Wall Street closed, New York gentlemen of the Gilded Age went calling. The protocol held that “each gentleman sends in but one card.” However, “if there is a card basket at the door, he leaves a card for each lady at the house.” Plans might be made known in advance so that groups of ladies might convene at one location to receive callers and offer refreshments, such as holiday punch in the “massive silver on the dining room tables,” a cherished memory of May Van Rensselaer. “Gentlemen call singly, by twos, or in small companies, on foot, or in carriages or sleigh.” The calls might be brief, “as short as five minutes,” or “protracted to half an hour.” Advised Etiquette of Visiting Cards, “It is good form for gentlemen who cannot make New Year’s calls to send them by special messenger in the morning.”

American Etiquette found the New Year’s calls an “agreeable custom,” which the elderly Mrs. Van Rensselaer underscored, recalling the “husbands, brothers, and fathers” who “voyaged about the city, touching at this or that hospitable home to exchange the compliments of the season.” But the younger socialite Elizabeth Lehr had a different view of the holiday. She recalled that her mother “and every other hostess in New York had sat in state in their drawing-rooms from ten in the morning until late in the afternoon to receive the calls of every bachelor whom they had entertained during the previous year.” The custom, said Mrs. Lehr, was fortunately “fading,” giving way to an era of “glittering hotels” and “restaurant parties.” Even as social life evolved, however, cards remained a Gilded Age necessity.

Parties and Balls

Parties

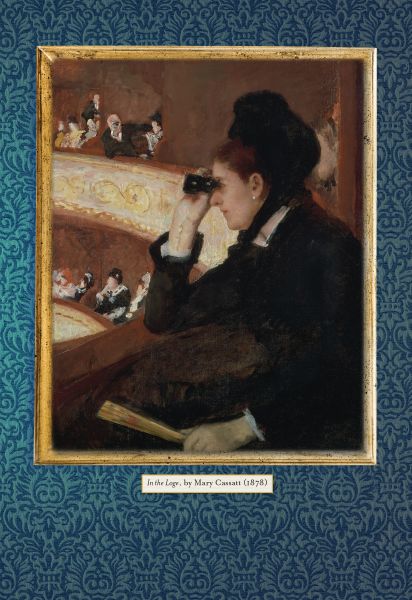

Gilded Age parties ranged from morning receptions to afternoon gatherings (usually from four to seven p.m.) to evening affairs. As always, appropriate dress was de rigueur. For men, a daytime party required morning dress, a waistcoat and striped trousers; for ladies, a “demi-toilette,” meaning a gown of fine fabric (velvet or silk) that broaches but stops short of formality (“no low-necked gown nor short sleeves”). “Her more elegant jewelry and laces should be reserved for evening parties,” according to Sensible Etiquette. Guests’ invitations, issued by mail or a trusted servant, might promise a vocal or instrumental performance, in which case guests were expected to remain in attendance for the “little ballads” or string cantata. (“It is the duty of the hostess to maintain silence among her guests during the performance of instrumental music as well as of vocal.”) If the gathering is sizable, advised Abby Buchanan Longstreet in Social Etiquette of New York, “half an hour is quite long enough to remain in crowded drawing rooms,” for “it is a kindness to the hostess to make a space for her many guests.” The refreshment table is “spread with delicacies,” but “it is the rare man who so dishonors his dinner as to eat at a mid-afternoon party,” even though young ladies were observed enjoying ices and oysters. Longstreet noticed that some relatively informal gatherings, more typical of daytime events, were taking place in the evening hours, “for the simplicity of detail spared it from the burdens of a party.”

One such “burden” of an evening party was the inevitable “dancing” that guests noticed on their engraved invitations. Properly educated ladies and gentlemen would have had instructions in dance, from the quadrille to the waltz, though no Society evening party included the vulgar new “animal dances” such as the bear hug or fox trot. (An ensemble of four musicians to provide dance music was considered adequate for an evening party.) The nocturnal hours dictated that gentlemen “should be in full evening dress, meaning a tailcoat, uncuffed trousers with striping along the outside seams, a vest, starched white shirtfront, wing collar, bow tie, and patent leather shoes.” The ladies’ “required” evening dress “should be less elegant than for a ball.”

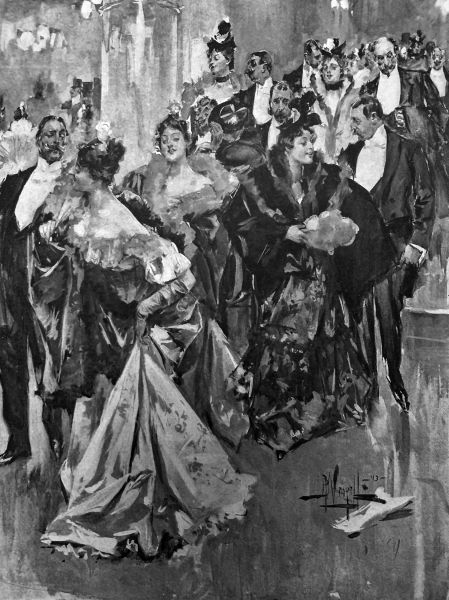

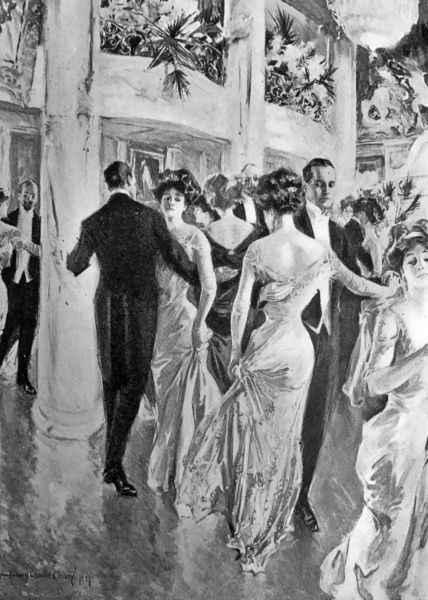

Balls

According to Social Etiquette of New York, a ball in the Gilded Age was “an assemblage exclusively for the dance,” and by tradition, it opened and closed with a waltz. Invitations were sent from ten days to two weeks before the event and replied to immediately. The ball would begin at ten p.m., according to the invitation, though Society understood that meant ten-thirty or later. Mrs. Astor’s annual ball took place on the last Monday in January at her home at 840 Fifth Avenue. As the New York Times reported, “This entertainment is always the most notable of the Winter, and it marks the climax of the season. As a gathering, it is the most representative of New York society,” the Times continued. “Although Mrs. Astor is very conservative, her list always includes not only the very fashionable element, the leading old families, but also any distinguished foreigners or visitors to New York.”

Emily Post explained the evolution of the ball from private homes to hotels. “A great ball in a private house,” she said, became a rarity because, no matter how ample the home, it was too small to “provide dancing space for several hundred and sit-down supper space for a greater number still,” not counting the ancillary spaces required (“a smoking-room, dressing-room, and sitting-about space”). Longstreet’s guide to New York etiquette adds other necessary spaces for floral arrangements and plantings such as palms or orange trees, for “garlands hung picturesquely” to “add color and beauty as lavishly as the hostess chooses to provide.” “The decorations for a ball cannot be too lavish or too beautiful,” added Post, and have, on occasion, “been astounding.”

Hotels such as the Waldorf-Astoria or Hoffman House were happy to accommodate the eager hosts and hostesses of Society, as were Delmonico’s and Sherry’s restaurants, each of which had large banquet hall and ballroom spaces. Two fashionable orchestras must be secured for the ball, Post’s Etiquette insisted, each taking its turn so that the music never stops. Inviting a lady to dance, the gentleman asks, “Shall I have the honor of dancing this set with you?” Afterward, the lady is returned to her place and smiles graciously as the gentleman thanks her for the honor she has conferred on him. Certain rules must be followed:

- 1. A lady will not cross a ballroom unattended.

- 2. A gentleman will not take a vacant seat beside a lady who is a stranger to him.

- 3. White gloves should be worn at a ball, and only be taken off at supper-time.

As for the nourishment, “a sit-down supper that is served continuously for two or three hours is the most elaborate ball supper.” At “the most fashionable New York balls, supper service begins at 1 a.m. and continues until 3 a.m.” A supper without champagne, Post noted, is unheard of. “The table is made elegant by beautiful china, cut glass, and a variety of flowers,” according to American Etiquette. “The hot dishes are oysters, stewed, fried, broiled and scalloped; chicken, game, etc.; and the cold dishes are boned turkey, chicken salad, raw oysters, and lobster salad.” There is no tipping by guests.

The astute observer of New York Society Henry James did not dance himself but closely observed the social scene, dazzled by the ladies in Society: “beautiful, gracious and glittering with gems, . . . in tiaras and a semblance of court trains, a sort of prescribed official magnificence.” Elizabeth Lehr, likewise a memoirist of the era, recalled, “Even after all these years I have only to close my eyes to conjure up a vision of the Astor ballroom in all its splendours,” including the Italian “massive candelabra” and “the long rows of chairs tied together with ribbons, . . . and on a raised platform at one end was an enormous divan—‘The Throne,’” on which the most privileged of the privileged sat with Mrs. Astor herself.

Gilded Age “Cinderella”

The story of Cinderella, rooted in Grimm’s Fairy Tales (1812), would have been a familiar one to American children through the 1800s and beyond. Sweeping cinders at the hearth, the toiling, humble maiden reveals her loveliness and sterling character to the prince in a serendipitous twist that sends her to the royal ball. Losing one shoe, she vanishes at the stroke of midnight, though the smitten prince afterward seeks her with the petite dance slipper that fits no maidenly foot in the kingdom but hers. When the shoe fits, she is Cinderella no more but a princess in the palace, “happily ever after.”

Outside the nurseries of the well-to-do, the story circulated as a folk tale promising a sort of lottery of good fortune for young women leading precarious lives in the city. Most were poorly paid department-store clerks at Macy’s or Lord & Taylor or chorus girls who hoofed on stages in the Bowery or in theatricals with titles such as Cleopatra’s Amours and Fifty Nice Girls in Naughty Sketches. The more likely prospect was to be found in the nationally prominent temperance movement leader Frances Willard’s Occupations for Women. Among the fifty-plus income-earning occupations that she endorsed, including stenographer and nurse (store clerking was exhausting, and women working as dance hall “dramatists” were beyond the pale), was the “professional mender.”

The mender, wrote Willard, could earn an “honest penny” as “nothing less than an angel with a thimble” who is “skilled with the needle” and is a “much-needed individual in hundreds of households.” In the past, the “old time gentlewoman could mend anything, from household linen to lace.” Home sewing machines had now made those skills obsolete, but no machine could replace the elegant stitches of the human hand. Any girl “who understands the art of darning and mending,” Willard promised, “would soon find that this sort of business paid.”

As indeed it did in one true Cinderella story of the Gilded Age. In a “tiny room” at the top floor of “Sherwood,” the Newport mansion of Mr. and Mrs. Pembroke Jones (of North Carolina), sat Mary Lily Kenan, who “sewed” and “sewed,” recalled the memoirist Elizabeth Lehr, who became the little seamstress’s confidante. Born in North Carolina in a family whose plantation property fared poorly in the Civil War and its aftermath, the freckled Mary Lily was “small and frail,” known as “plain” and rather like a “little mouse.” The “nearest she ever got to one of the splendid balls was to peep over the stairs and watch beautiful women so lovely they made her catch her breath in ecstasy. . . . No one had ever been in love with her.” In her midthirties, the likelihood of romance seemed remote. However, “for all that she was a romantic” and “always dreamt that a fairy prince would come into her life and take her away from the tiny room and the sewing.”

“One day Henry Flagler, multi-millionaire, elderly, disillusioned with life, arrived in Newport,” recalled Lehr. “Everyone knew that he had been divorced, and that he had no heart for balls or entertainment.” As the Jones’s houseguest at “Sherwood,” he asked only to rest, to be a “hermit.” There would be no dinners in his honor, no excursions. Even with this slow pace of activity, as it happened, a button popped off his coat, and naturally the hosts summoned Mary Lily. Recalled Lehr, Mary Lily, who “came down, very shy, took the coat in her little hands, her small freckled face bending over the needle” while “the millionaire watched as she sewed.”

“But the next day she came to Mrs. Pembroke Jones, still very quiet, mouselike, but a new Mary Lily.” She announced, “I am going to marry Mr. Flagler. He loves me and I love him.” No longer was she “Cinderella,” wrote Lehr, but “a princess come into her own kingdom.”

In a flash, wedding preparations were under way. “I have had her taken out of the servants’ quarters and put into the best guest suite with two footmen to wait on her,” said Mrs. Pembroke Jones. “Nothing can be too good for her now! The yacht has gone to New York to bring back dresses from Worth and jewels from Tiffany’s. Henry Flagler says she is to have everything in the world she wants, if it is in his power to get it.”

Indeed, nothing would be too good for the third Mrs. Flagler. In Lehr’s words, “A wave of the magic wand and Cinderella was arrayed in the silk and laces of the fairy story, or, to be more precise, in the latest Parisian creations which Worth’s sales-women and their attendant bevy of . . . fitters had brought down to Newport.” Though they suggested a “misty blue tulle,” the romantic Mary Lily chose “the traditional white satin and lace veil,” the “wedding dress of her dream.” Walking down the aisle on the arm of her bridegroom on August 24, 1901, “she looked a little bewildered,” but “her smile was radiant.” The wedding took place in North Carolina on the grounds of the Kenan property, after which the couple planned to spend winter seasons in Whitehall, the new fifty-five-room Beaux-Arts mansion in Palm Beach, a wedding gift to Mary Lily from her bridegroom.

Figure 24. Mrs. Henry Flagler (née Mary Lily Kenan) in Palm Beach

Upon the death of Henry Flagler in 1913, Mary Lily inherited his fortune and became a benefactor of numerous causes based in her home state, North Carolina, as well as the new wife of Judge Robert W. Bingham of Louisville, Kentucky.

Seen but Not Heard

In 1897, a New York Times editorial proclaimed that “given one generation of children properly born and wisely trained, what a vast proportion of human ills would disappear from the face of the earth!” No one in Mrs. Astor’s circle would disagree. The parents in the Four Hundred well understood that their child rearing should be exemplary, its motto “children should be seen and not heard.”

From infancy, a child of Society occupied the nursery strategically situated at the outer reaches of the household so that squalls and cries would spare the adults’ ears. The live-in nurse was in charge, reported to the parents, and brought forth the child or children only at the appointed times of day for moments of social cheer and parental instruction in proper manners. A young boy under the age of ten might wear a sailor suit with short pants, and a little girl of three, a skirt and reefer jacket. When presented to their parents or other family members, and perhaps to guests, strict rules applied. Most were prohibitions.

“Never” is the recurrent word in “Etiquette with Children” in Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society, for example,

Never take a child to church until it is old enough to remain perfectly quiet.

Never crowd children into pic-nic parties if they have not been invited. They generally grow weary and very troublesome before the day is over.

Never permit children to handle the ornaments in the drawing-room of a friend.

Never take a child to spend the day with a friend unless it has been included in the invitation.

Never crowd a child into a carriage seat between two grown people.

Never send a child to sit upon a sofa with grown people, unless they express a desire to have it so.

Never allow children to be in the drawing room if strangers are present.

Never allow a child to pull a visitor’s dress, play with the jewelry or ornaments she may wear, take her parasol or satchel for a plaything, or in any way annoy her.

Never let a child play with a visitor’s hat or cane.

This Never-Never land of etiquette for youngsters was governed above all by the principle of bodily restraint and utter silence. A child was not to speak unless spoken to—and only then with excellent comportment. Civilization itself was at stake, with irreproachable manners “an immense social force,” according to the guide.

One child’s testimony from Gilded Age New York opens a window onto the vexed issue of manners. At the home of the Clarence Day family at 420 Madison Square, Clarence Jr., along with his younger brothers, George and Harold, romped in their basement-level nursery. As the oldest son, young Clarence chronicled the miseries of dancing school, violin lessons, clean fingernails, and the mandatory “formal” clothing that precluded the workingman’s overalls he craved.

The nursery, however, was the Day lads’ domain and play room. After school, they acted out epic battles on land and sea with lead soldiers and the rocks that were once their father’s geology specimens—all undisturbed by parents or the servants. The boys’ dinners were served in the nursery on mismatched crockery with pictorial images (a buffalo, a military insignia). After seven p.m., when the servants had cleared the table following Mr. and Mrs. Day’s dinner in the upstairs dining room, the boys “went trooping in” to visit their parents in the solemn dining room that young Clarence revered as “a high court or shrine.”

To Clarence’s initial delight, he was promoted at age seven to this “sacred” space to dine nightly with his parents, and he bade farewell to the “little boys.” His account: “I found almost at once that the honor I had won was a hollow one. It was also oppressive. The free and easy interchange which I had been used to at my meals with my brothers down in the basement, was gone. I had been cock of the roost in the basement, but now I had to keep still, and respectfully say Yes sir and No sir, and submit to being taught what seemed to me many superfluous manners. I had to use plain china too instead of the interesting kind we had in the basement.”

The account of Clarence’s woes proceeds to a contretemps with his father over a dish of mashed turnips. The fundamental lesson Clarence absorbed from his rearing was that “children were children, and grown-ups were grown-ups, and the two weren’t expected to mix.” “We looked upon grown-ups as foreigners,” he concludes. “And they felt the same way about us.” The elder Days’ tutelage nonetheless eventually won out, for young Clarence became an alumnus of prep school, Yale, Wall Street, and genteel New York—in short, a gentleman.

What They Read

Showplaces of good taste and refinement, the libraries of the Four Hundred featured sets of leather-bound volumes that elevated these rooms to “importance.” Edith Wharton suggested in her advice manual, The Decoration of Houses, that “old volumes” bound in “half morocco or vellum form an expanse of warm lustrous color.” Décor was essential, but actual reading was another matter entirely. The leather-bound editions of Shakespeare’s plays or calfskin classics of ancient Greece and Rome were displayed but need not be opened. Their presence alone certified the household as consummately civilized.

Child rearing, however, required the diligent oversight of sons’ and daughters’ reading matter. Edith Wharton thought her parents and their circle “held literature in great esteem” but “stood in nervous dread of those who produced it.” The stakes were high. “Books are windows through which the soul looks out,” proclaimed Manners, Culture and Dress of the Best American Society. It posed these questions: “Parents, through what kind of windows are your boys and girls looking out upon the great world of to-day and of ages past? Are they beholding things pure or pernicious, noble or degrading, sublime or silly, virtuous or vicious?” Wharton recalled her mother fretting over her own “Pussy’s” exposure to the right books and her decree that the child “should never read a novel without asking her permission.” Young Clarence Day Jr. gave no thought to these issues when he read and reread Gulliver’s Travels and King Solomon’s Mines in his family’s Madison Square home. Nor did Blanche Oelrichs, who from “earliest childhood” sat at the table in Newport to read Dotty Dimple and the Little Elsie series but graduated by age eight to Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Walter Scott, The Blue Fairy Book, and an edition of The Arabian Nights that she filched from the top shelf of a neighbor’s library. The author of Manners would have been appalled at these selections. His suggestions for children of the Gilded Age included

- Hezekiah Butterworth, Zig-Zag Journeys in Europe

- Charles Carleton Coffin, Our New Way Round the World

- Thomas W. Knox, Boy Travelers in Australasia (also in Mexico; in South America in Japan and China; in Siam and Java; in Ceylon and India; in Egypt and the Holy Land)

- Jules Verne, Exploration of the World (volumes 1–3)

- Walter Scott, Ivanhoe, Kenilworth, and The Heart of Midlothian

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Paul Revere’s Ride, The song of Hiawatha, and The Courtship of Miles Standish

The ladies and gentlemen of New York and Newport, all the while, consumed “stacks of novels” that Edith Wharton termed “ephemeral rubbish,” though certified by the authors’ British lineage and presumably uplifted by virtue of settings in Britain or its colonies. Sir Walter Scott was sanctioned, as was Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (for “pleasure and profit”). A “good book” was “one in which the bright rather than the dark side of life is shown” and “one that we want when weary of the people of the world.” What Shall I Read: A Confidential Chat on Books cautioned, “Never read the books of any novelist till you have acquainted yourself with his reputation.”

Some popular novelists of the Gilded Age that withstood scrutiny include George Whyte-Melville (1821–1878), a Scotsman whose fiction focused on field sports, principally hunting, and whose best-liked novels include Digby Grand, Tilbury Nogo, The Honourable Crasher, Mr. Sawyer Coventry, Kate Coventry, Mrs. Lascelles, The Gladiators, and Legend of the True Cross; and Rhoda Broughton (1840–1920), a British writer who offered ladies of the Gilded Age novels about the conflicts over true love, womanhood, motherhood, and the perils of a poet, including A Beginner, Dear Faustina, The Game and the Candle, Lavinia, Scylla or Charybdis, and A Waif’s Progress. Edward Jenkins (1838–1910), a British barrister, became well known for satirical novels in the 1870s–80s, copies of which were available in gentlemen’s clubs in Britain and New York, including Ginx’s Baby: His Birth and Other Misfortunes, Barney Geoghegan, M.P., and Home Rule at St. Stephen’s, Lord Bantam: A Satire, Little Hodge, The Devil’s Chain, The Captain’s Cabin: A Christmas Yarn, Haverholme, or, The Apotheosis of Jingo: A Satire, A Week of Passion, or, The Dilemma of Mr. George Barton the Younger: A Novel, and A Secret of Two Lives.