Dinner Is Served

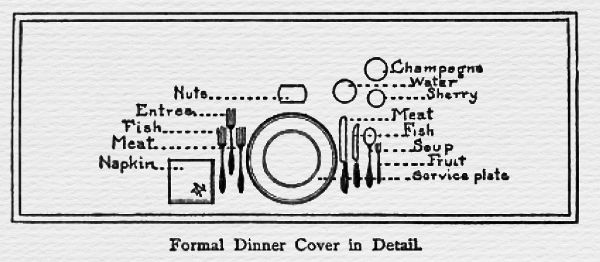

The Proper Place Setting

The crystal sparkles, the china shines, the silver glows, and the damask napkins await the guests to be assembled for dinner. “To merit the title of lady or gentleman,” asserted an 1883 guide to good manners, “it is necessary to show good breeding by gentility at the table.” No member of the Four Hundred needed coaching on this point. As children, they were schooled in table etiquette by their governesses and parents. By the time they entered Mrs. Astor’s formal dining rooms, they were well versed in the use of an oyster fork and fish knife. For the Gilded Age elites of New York, breakfast was somewhat casual, and luncheon varied in formality. The protocol for a formal dinner, however, was set in stone, predictable for guests and hosts alike.

All concurred with Emily Post’s Etiquette that “to give a perfect dinner of ceremony is the supreme accomplishment of a hostess.” Mrs. Astor and the ladies of her social set relied on an experienced corps of servants that ranged from the secretary to the cook, the butler to the footmen. They were the precision instruments in service to the great event. The guest list would be “quickly edited” to bring “last year’s list of guests up to date, adding here, erasing there, as deaths, débuts, and divorces necessitate.” The seating was arranged so that personalities harmonized, the “younger set” and eminent elders mixed to prompt a “social salad” of bright conversation. The guests of honor, perhaps a duke and duchess or other grandees, were duly assigned to the right and left of the host and hostess, each of whom would sit at an end of the table. (In planning, the hostess would “approve her secretary’s suggestions as to additional names if those first invited send ‘regrets.’”) The place cards were inscribed and tucked into envelopes given to the butler for positioning after the table was set.

The setting itself required meticulous preparation. A trusted footman, for instance, cleaned the glassware and fervently polished the silver with a “rouge chamois,” each piece then washed separately and “given a quick wipe-off as it was laid on the dining table.” (“No silver should ever be picked up in the fingers,” warned Etiquette, “as that always leaves a mark.”) The table furnishings must include “faultlessly laundered linen” and “brilliantly polished silver.”

The experienced hostess might well entrust the menu to her capable cook, confident that the gentleman guests need not “go home and forage ravenously in the ice box.” Etiquette, however, cautioned:

Under no circumstances would a private dinner, no matter how formal, consist of more than:

- 1. Hors d’oeuvre

- 2. Soup

- 3. Fish

- 4. Entrée

- 5. Roast

- 6. Salad

- 7. Dessert

- 8. Coffee

The dinner would typically commence at eight p.m. in the city, half past eight in Newport.

“Fifteen minutes before the dinner hour,” said Post, “the hostess is already standing in her drawing-room.” Awaiting her guests, “she has no personal responsibility other than that of being hostess. The whole machinery of equipment and service runs seemingly by itself.” The guests will arrive some ten minutes after the hour indicated on the invitation, the doors of their carriages or motor cars to be opened by the host’s groom, who ushers them onto the carpet that has been laid from the city sidewalk to the front entrance, while a sheltering awning provides protection from the elements. The footmen are on duty in the hall, and the maid is in the ladies’ dressing room to assist with wraps and predinner primping, just as the valet awaits the gentlemen in another room to help as needed with coats and hats. “The hostess receives her guests,” approved Post’s Etiquette, “with the tranquility attained only by those whose household—whether great or small—can be counted on to run like a perfectly coordinated machine.”

For those who lacked a governess or tutor, the etiquette guides would have to suffice. They encouraged “cheerfulness in the dining room” and insisted that “the charm of good housekeeping lies in a nice attention to little things, not in a super-abundance.” Walter Raleigh Houghton’s popular American Etiquette advised that “the dining-room, the table and all the appurtenances should be as cheerful as possible,” and “the room should be comfortable, bright and cozy.” At the table, “the hostess should wear her brightest smile.” Whenever a crash or other intrusive noise is heard from the kitchen, everyone at the table is advised to pretend they hear nothing. Howsoever, impeccable manners must prevail from the hors d’oeuvre to the coffee.

In “General Rules of Table Etiquette,” Houghton was unsparing of prohibitions. Among them were the following:

- When you are at the table do not show restlessness by fidgeting in your seat.

- Do not play with the table utensils, or crumble the bread.

- Do not talk loud or boisterously.

- Do not bend the head low down over the plate. The food should go to the mouth, not the mouth to the food.

- Do not talk while your mouth is full.

- Never make a noise while eating.

- Never tilt back your chair while at the table, or at any other time.

- Never indicate that you notice anything unpleasant in the food.

- Do not break your bread into soup, nor mix with gravy.

Sensible Etiquette added other strictures. A wine glass should be “held by the stem, not by the bowl,” and one must “never drink a glassful at once, nor drain the last drop.” Asparagus, olives, and artichokes may be eaten with the fingers, but other “vegetables are eaten with a fork.” “Cheese is eaten with a fork, and not with a knife.” One must “never play with food.” The diner in need of a servant’s assistance must “catch his eye” and make the request “in a low tone.” Finally, “anything like greediness or indecision must not be indulged in.” The table itself, Post’s Etiquette insisted, must be free of “pickle jars, catsup bottles, toothpicks and crackers.” All condiments must be “put in glass dishes with small serving spoons.” “Nothing,” she added, “is ever served from the jar or bottle it comes in except certain kinds of cheese.”

The “perfectly coordinated machine,” however, could sputter on occasion, especially when the “younger set” attempted such dinners. “No novice,” warned Etiquette, “should ever begin her social career by attempting a formal dinner.” The pitfalls were many, starting with the overambitious cook whose ill-timed dishes curdle or burn, whose soup is watery, whose roast dry as wood. The guests might find that a chambermaid pressed into service at the table has no notion of proper serving or clearing, crudely stacking guests’ plates atop one another in a clattering armful and clutching the silverware in a fist.

Following the dinner, the gentlemen “saunter into the library for cigars and coffee,” their conversation ranging from recent moves in the stock market to prospects in next year’s polo matches. The ladies may “glide into the drawing room” for coffee and cigarettes, their topics of choice their children and current fashions such as the new “hopeless” hats. (“Of course, one will have to wear them.”) “After coffee, any guest may take leave,” advised Social Etiquette of New York, and “it is not expected that the latest lingerer will remain longer than two hours after dinner.”

Table manners of the rich arrivistes, however, were another matter. As the social observer Albert Stevens Crockett noted, a “crowd” of “hard-boiled, new-money men from the Golden West or Southwest” began to “descend upon New York.” An exasperated May Van Rensselaer agreed, decrying the “steel barons, coal lords, dukes of wheat and beef, of mines and railways” who had “sprung up from obscurity.” She called them “interlopers.” Edith Wharton called them “invaders.” Perhaps, said Crockett, they first “gained the knowledge of the appearance, taste, and possibilities of French cuisine” in San Francisco or Denver or the silver boomtown of Nevada’s Virginia City. In every way, said Crockett, “their appetites were huge and primitive.” Their comportment at the dining table, however, would be tested in New York. American Etiquette put the matter bluntly: “The distinction between the gentleman and the boor is more clearly noted at table than anywhere else.”

In one droll advisory, Francis (Frank) Crowninshield, a Bostonian adopted by New York Society, struck a note of irony in a tome designed to explain table manners to “Our Country Cousins” or the newly arrived “rich Westerner.” “Green peas,” advised Crowninshield in Manners for the Metropolis (1905), “are eaten with the aid of a fork,” for “the hair-raising spectacle of a gentleman flicking peas into his mouth with a steel knife is no longer fashionable, however dexterously the feat may be performed.” The uninitiated were advised that “in using a finger bowl,” they must “simply dip the index finger into the fluid and pass it lightly over the lips.” However, they must “make no effort to consume the floating lemon.” Nor ought they to splash about in the water, “like a playful walrus or a performing seal.” In addition, the bumpkins were warned away from the terrapin, hard crabs, or asparagus that were certain to overtax their skills at the table. “Be content to poke and pat these dishes with a fork, but make no effort to consume them unless accustomed to them by birth.”

Crowninshield and his elite readers were accustomed to fine manners by birth, and by entitlement they were free to poke with the fork—or the pitchfork—of wit. But the rustics were on the march. Said May Van Rensselaer, “In a great glittering caravan the multimillionaires of the midlands moved up against the city and by wealth and sheer weight of numbers broke through the archaic barriers.” Their chefs would crack the crabs, their footmen serve the terrapin. “When they had attained the places they desired,” Mrs. Van Rensselaer concluded, “only one general qualification for social acceptance remained—wealth.”

New York’s Elegant Restaurants

Dinner was its own occasion, and dinner and the theater were often paired in the Gilded Age as they are today. An early or pretheater dinner, however, was out of the question. New York theatergoers and diners, including Society, would never imagine an “early-bird” evening meal. Dining late or after the play was the thing, and New York restaurateurs provided sumptuous fare within easy reach of the theaters. The dining destinations were a study in sociology, for the restaurant scene divided class and caste. Crowds eager for spectacle sought the boisterous lobster palaces such as Rector’s or Murray’s Roman Gardens. For them, the stage play was the first theatrical event of the evening, and the late-night supper and champagne-fueled wee hours guaranteed another act or two.

For Society, two restaurants met the standard that was expected by those for whom money was no object.

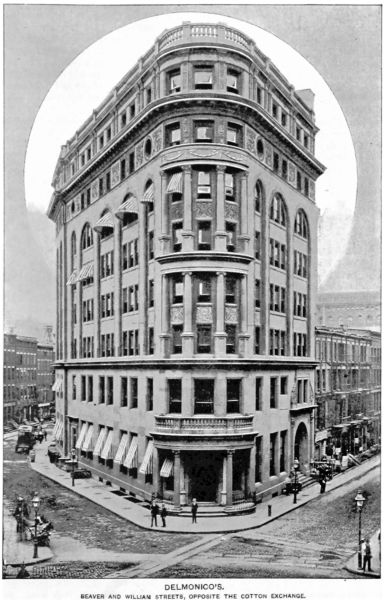

Delmonico’s

By the Gilded Age, three generations of New Yorkers knew the name of the dining establishment that had secured a beachhead in a city formerly content with merely eating. The Swiss brothers Giovanni and Pietro Del-Monico opened their first European-style café in 1827, when the main midday meal in New York was typically wolfed down without conversation. The success of the brothers’ innovative oasis of French pastries, chocolate, wine, and liqeurs led to the opening of a popular restaurant, destroyed by fire in 1835. Now known as the Delmonico brothers, the two seized on the opportunity to buy a triangular lot located near Wall Street at the intersection of Beaver, William, and South William Streets and built an elegant brick-and-brownstone building rising three and a half stories. The restaurant accommodated parties, balls, and private dining, and the wine cellar was unsurpassed in the city. Old New York had dined at Delmonico’s from the 1830s, and accordingly old and new money followed suit in the Gilded Age. As the city moved northward after the Civil War, Delmonico’s kept pace, relocating to Fourteenth Street and Fifth Avenue, once again with amenities for private parties and debutante balls.

From dinner until closing, Delmonico’s celebrity chef, Lorenzo, supervised the kitchen, while his brother, Charles, charmed guests in the dining room. With the restaurant attracting a wealthy clientele, Lorenzo favored expansion, and four Delmonico’s restaurants dotted the city in the decade following the Civil War. In 1876, the famed restaurant’s newest location opened at Twenty-Sixth Street between Broadway and Fifth Avenue within sight of Madison Square. The first floor featured a café, but the floor above assured privacy with its “regal red and gold” ballroom and four private dining rooms. Additional dining rooms and a banquet hall occupied the third floor, and on the fourth lived a few “confirmed bachelors” in permanent residence.

Figure 27. Delmonico’s restaurant, Beaver and William Streets, 1893

Delmonico’s silver chandeliers, mirrors, frescoed ceiling, and central fountain surrounded by fresh flowers delighted the patrons. The Vanderbilts hosted parties in the private rooms, and Ward McAllister’s elite Patriarch Balls took place in the ballroom. They dined in the company of American presidents, European aristocrats, leading politicians, and celebrities such as Charles Dickens and Oscar Wilde. The patronage was not limited to Society. Tammany Hall’s notorious “Boss” Tweed celebrated his daughter’s wedding with a reception catered by Delmonico’s in 1871, and nine years later, Thomas Edison tapped the marquee restaurant to cater a banquet for investors he wooed to underwrite his plan to electrify the streets of New York. The dizzying momentum of the Gilded Age was measured yet again in 1891, when Delmonico’s opened an eight-story restaurant and café at Fifth Avenue and Forty-Fourth Street, featuring “brilliant electric lights and many mirrors,” rare marble and fine woods, and a ladies’ dining room on the second floor.

From the first, the menu schooled New Yorkers in French gastronomy. Lorenzo could be found at dawn selecting exquisite produce at the Washington market and the freshest seafood at Fulton Street. Though American favorites such as oysters and canvasback duck were on the bill from the beginning, diners learned that partridge could be prepared eight different ways and veal a dizzying forty, including blanquette de veau. New Yorkers learned about truffles and artichokes, eggplant and endive. A featured dessert by the 1880s was Baked Alaska (“ice cream surrounded by an envelope of carefully whipped cream,” swooned the British journalist George Sala, and “popped into the oven,” so that its surface is “covered with a light-brown crust just before the dainty dish is served.”) Dinner at Delmonico’s, reported Harper’s Weekly in 1884, “was not merely an ingestion, but an observance,” and it called the restaurant “an agency of civilization.” (Albert Stevens Crockett noted, however, that “over-eating—if not over-drinking—became the cardinal vice of many a ‘sudden’ American millionaire—and not infrequently of his wife.”)

Feasts at Delmonico’s were legendary, none more so than the Swan Dinner hosted in February 1873 by the wealthy importer Edward Luckmeyer, splurging with an unexpected $10,000 refund on custom duties (about $203,000 today). Giving Lorenzo carte blanche to conjure up a banquet for seventy-five persons, Luckmeyer anticipated a menu and theatrical décor of unprecedented glory—one to exhaust every cent of his windfall. Guests arrived to find an “aquatic-gastronomic masterpiece,” a vast table filling the main dining room with a thirty-foot lake at the center, as well as little waterfalls, brooks, landscaped hillocks, and exotic plants. Songbirds sang from suspended cages, and flowers abounded. At the center of it all, a pair of swans glided on the lake (confined in a gold wire cage fashioned by Tiffany).

Society’s own swan, Mrs. Astor, put her imprimatur on the Delmonico’s at Madison Square. Escorted by Ward McAllister on the occasions when she “evinced her democratic tendencies by dining in the restaurant,” patrons enjoying partridge and champagne might best recall not their dinner but their sighting of the Mrs. Astor.

Sherry’s

Like Delmonico’s, the story of its rival Sherry’s is one of a capital city expanding in population as it grew exponentially in wealth. The son of a French carpenter from Vermont, Louis Sherry (b. 1855) studied the workings of restaurants from his first jobs as a New York hotel waiter. Schooling himself in the tastes and demeanor of fashionable diners, he secured financing from patrons who backed the young man’s plan to open a modest confectionary. He also traveled to Paris to observe the experience in restaurants in the culinary headquarters of the Western world. Back in New York, Sherry got two lucky breaks: a contract to provide refreshments at a gala fair at the new Metropolitan Opera House and a similar arrangement at a social event with the improbable name of the Badminton Assembly. With his new reputation as a caterer, Sherry planned a restaurant to be on par with Delmonico’s, and in 1890, with investors’ backing, he bought the former Goelet mansion at Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Seventh Street to house a ballroom, a confectionary, and his small restaurant. But Sherry needed additional square footage to match his ambition, and he commissioned Stanford White to design a twelve-story edifice at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Forty-Fourth Street to open in 1898. Underscoring the point, the new Sherry’s rose on the opposite corner from Delmonico’s. When Mrs. Astor appeared in white satin and diamonds to join others of the Four Hundred, Sherry’s was certified for Society.

Figure 28. If not Delmonico’s or Sherry’s, dinner at the Waldorf

Louis Sherry had learned a lesson from the Delmonico brothers: complaints about high prices were not important, but a diner’s qualms or complaints about the food or service should be addressed immediately. Sherry’s motto was “Never disappoint a customer.” The palatial Sherry’s, some felt, was flashier than “Dels,’” and the Herald reported that Sherry’s ballroom filled with the younger crowd, while Delmonico’s was left with “wall flowers, old timers and patricians.” Edith Wharton included a scene at Sherry’s in her best-selling novel of 1905, The House of Mirth, whose impecunious heroine, Lily Bart, has been disinherited by her late, rich aunt, who believed false rumors of her niece’s scandalous conduct. Now Lily lunches at Sherry’s with a near-hysteric abandon, ready to fling her few remaining dollars for the sort of experience suitable for a lady of her upbringing, equivocating, “What sweet shall we have today—Coupe Jacques or Pêches à la Melba?”

Sherry’s was also the site of an “experiment” in decorum recounted by Elizabeth Lehr in a chapter of her memoir titled “Revolution at Sherry’s.” The revolution in question was a plan by two doyennes of Society, Mamie Fish and Frances Burke-Roche, to dine bareheaded and to reveal their necks and bosoms in the décolleté low-cut gowns fashionable abroad. Entering Sherry’s dining room one Sunday evening, the pioneering ladies heard “audible comments of ‘bold,’ ‘shameless,’ and ‘disgusting.’” “Louis Sherry turned pale with indignation,” reported Mrs. Lehr, but “retained his poise” when he recognized the ladies. “Only from such celebrated leaders of society could he have tolerated so scandalous an infringement of the rules of etiquette.” The experiment was a “success,” she concluded, but Louis Sherry’s “disapproval was evident.”

The Lobster: From Prison Fare to Haute Cuisine

Massive restaurants offering pig-out portions are nothing new to New York tourists. They are a Times Square tradition that can be traced to the Gilded Age, when the theater district was known as Long Acre Square. With crowds of the newly affluent looking to be fed and entertained, Rector’s, at Broadway and Forty-Fourth Street, helped to usher in the “lobster palace” craze, while Murray’s Roman Gardens, Cafe Martin, and others made eating vast quantities of elegant-sounding foods trendy among tourists and the middle class. These venues deliberately imitated the décor and menus of Fifth Avenue hotels and Society haunts such as Sherry’s and Delmonico’s but abandoned their exclusive atmosphere in favor of ostentation and Broadway theatricality. In the heyday of these eating emporiums, lobster was king.

This had not always been the case. From colonial days, new settlers from Boston to New York were horrified at the notion of eating the monstrous insect-like crustaceans with scaly exoskeletons and outsized pincer claws. Though specimens could be readily glimpsed prowling the seafloor or lurking in crevices, no one thought them edible, not even during the “starving time” when meat was as scarce as it was prized. (Natives Americans used lobsters to fertilize their fields.) The seafood most prized in New England from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries was cod, fresh or salted and dried, a mainstay in boiled dinners, chowders, and hash.

In the 1800s, Bostonians and New Yorkers began gradually to accept the idea of edible lobster, a lowbrow meal for those who were unworthy of cod, namely, the sailors, the down-and-out, indentured servants, and prisoners. (Terms of employment in Massachusetts and Maine guaranteed that mariners and servants were to be served lobster only twice weekly. Prison inmates, equally repulsed by frequent lobster rations, were in no position to bargain it away.) Lack of refrigeration was a factor. Dead shellfish fare no better than other seafood, and overripe lobster assaulted the senses.

Greater acceptance of the possibilities of lobster began, it seems, with the 1800s development of a fishing boat called a “lobster smack,” whose deck held wells or tanks that kept the crustaceans alive. By 1850, lobstermen worked close to shore using the traps that became the hallmark of the fishery. Early recipes insist that a chef or cook commence with a live lobster. The crucial test for the chef or restaurateur in New York was whether a lobster flexed its claws and whipped its tail. Later, canneries arose along the New England coasts, and lobster meat was packed for shipment inland. Railroad express trains and plentiful ice assured freshness by rail to areas far from the shore.

Enter Escoffier

The apogee of French cuisine in the Gilded Age was expressed, quite simply, in a single word: Escoffier. Referred to as roi des cuisiniers et cuisinier des rois (king of chefs and chef of kings), the recipes and techniques of the master French chef George Auguste Escoffier dominated the kitchens of the Paris Ritz and the Savoy and Carlton Hotels in London and were copied (or approximated) in the kitchens of New York’s Fifth Avenue and in the summer “cottages” in Newport. Escoffier’s essential La Guide Culinaire, both a textbook and a compilation of recipes published in 1903, includes menus to assist chefs wherever they sharpened their knives or heated their bouillon in preparing to confront the lobster.

Among the two dozen lobster recipes included in Escoffier’s Guide was one featured prominently at a “Servants’ Ball” at “The Rocks,” Elisha Dyer’s summer home in Newport. Among those who were costumed—as ladies’ maids, cooks, valets, chauffeurs, and footmen—was “cook” Elisha Dyer, who contributed to the “funniest” part of the evening by actually cooking “lobster à l’Américaine.”

Lobster à l’Américaine

The first essential condition is that the lobster should be alive. Sever and slightly crush the claws, with the view of withdrawing their meat after cooking: cut the tail into sections; split the shell into two lengthwise, and remove the queen [a little bag near the head containing some gravel]. Put aside, on a plate, the intestines and the coral, which will be used in the finishing of the sauce, and season the pieces of lobster with salt and pepper.

Put these pieces into a saucepan containing one-sixth pint of oil and one oz. of butter, both very hot. Fry them over an open fire until the meat has cooked well and the shell is of a fine red color.

Then remove all fat by tilting the saucepan on its side with its lid on; sprinkle the pieces of lobster with two chopped shallots and one crushed clove of garlic; add one-third pint of white wine, one-quarter pint of fish fumet, a small glassful of burnt brandy, one tablespoon of melted meat-glaze, three small, fresh pressed and chopped tomatoes (or, failing fresh tomatoes, two tablespoons of tomato purée), a pinch of chopped parsley, and a very little cayenne. Cover the saucepan, and set to cook in the oven for eighteen or twenty minutes.

This done, transfer the pieces of lobster to a dish; take out the meat from the section of the tail and the claws, and put them in a timbale; set upright the two halves of the shell, and let them lie against each other. Keep the whole hot.

Now reduce the cooking sauce of the lobster to one-third pint; add the intestines and the chopped coral, together with a piece of butter the size of a walnut, set to cook for a moment, and pass through a strainer.

Put this cullis into a pot; heat it without letting it boil, and add, away from the fire, three oz. of butter cut into small pieces.

Pour this sauce over the pieces of lobster which have been kept hot, and sprinkle with a pinch of chopped and scalded parsley.

Also included among Escoffier’s recipes was a particular New York favorite, Lobster Newberg, featured on the menus at both the popular lobster palaces and the ritzy Delmonico’s. But Lobster à la Newberg had an intriguing creation story that was apparently unknown even to Escoffier.

In the late 1870s, among the regular patrons at Delmonico’s Madison Square Café was a dandified sea captain, Ben Wenberg, who plied the fruit trade between Cuba and New York. Arriving to dine one evening, Wenberg announced his discovery of a new method for cooking lobster. He called for a chafing dish with a spirit lamp (termed a “blazer” at the time) to be brought to his table, where he prepared a dish made of lobster, cream, unsalted butter, French cognac, dry Spanish sherry, and cayenne pepper. Charles Delmonico proclaimed the concoction “delicious!” and named the dish “Lobster à la Wenberg” after his creative guest.

Alas, Captain Wenberg and Charles Delmonico quarreled, and the immensely popular Lobster à la Wenberg was banished from the menu. Delmonico patrons clamored for the dish, however, and Charles relented, somewhat. The dish reappeared on the menu as “Lobster Newberg.” Escoffier’s recipe suits proportions for an evening at Delmonico’s or the lobster palaces.

Lobster à la Newberg

Cook six lobsters each weighing about two pounds in boiling salted water for twenty-five minutes. Twelve pounds of live lobster when cooked yields from two to two and a half pounds of meat with three or four ounces of coral. When cold detach the bodies from the tails and cut the latter into slices; put them into a sautoir [saucepan], each piece lying flat, and add hot clarified butter, season with salt and fry lightly on both sides without coloring; moisten to their height with good raw cream; reduce quickly to half; and then add two or three spoonfuls of Madeira wine; boil the liquid once more only, then remove and thicken with a thickening of egg yolks and raw cream. Cook without boiling, incorporating a little cayenne and butter; then arrange the pieces in a vegetable dish and pour the sauce over.

Abjured in the first centuries of colonial settlement, the lobster made up for lost time in the Gilded Age of Lobster Palaces. Rector’s drew the admiring gaze of Theodore Dreiser, who pronounced it the height of all that was “sumptuous.” The restaurant beckoned patrons to an interior wherein “handsome chandeliers” threw a “blaze of incandescent lights” that shone on glazed tile floors and on walls of “rich, dark, polished wood.” Rector’s main interior attraction was “the long bar, . . . a blaze of lights, polished wood-work, coloured and cut glassware, and many fancy bottles . . . with . . . a line of bar goods unsurpassed in the country.” According to another close observer of the Gilded Age, “relaxations offered by Broadway after dark might include the fashionable lady who went to Rector’s “incognito” in a “hat with the largest and floppiest” of brims “in the hope that nobody would recognize her during her evening’s adventure.” Her escort “would be bidden to select one of the less illuminated tables in a distant part of the room.” She dare not wear a décolleté gown, lest she “put herself in a class with the feminine habitués who were not bound by caste and tradition.”

Eventually the lobster palace became a casualty of temperance reformers. In an effort to satisfy patrons eager to wash down their after-theater lobster feasts with magnums of champagne, liquor licenses had allowed palaces to serve alcohol around the clock, but new ordinances in the 1910s forced closure by one a.m. The era of Prohibition was on the horizon when the New York City mayor Ardolph L. Kline denounced the lobster-palace crowd for wee-hours “roystering” and often “openly immodest” behavior. “They get intoxicated,” he scolded, “behave boisterously, and indulge in lascivious dancing in rooms devoted to that use.” The palace doors closed when income from champagne and other alcoholic beverages no longer flowed throughout the night. Nonetheless, our love of lobster as the epitome of haute cuisine lives on.

The Grain and the Grape

In the battles that flared over alcohol in the Gilded Age, Mrs. Astor’s Four Hundred were ready combatants—of a sort. In a contest over liquor laws and the closing of saloons, their aims were purer. Let the hoi polloi imbibe raw spirits and quaff mugs of ale on the Lower East Side and the immigrant Germans down their steins of beer on Sunday afternoons; Fifth Avenue and Newport jousted on a different social plane. The right vintage or distillery, the right year, the right label meant the difference between the savoir faire of the Four Hundred and the gaucherie of the newly rich who bid to join their ranks. This was not a conflict between drinkers and teetotalers, the “wet” versus the “dry,” but a tussle over social superiority based on the elusive but distinctive category known as good taste. It was a confrontation between old money and what Edith Wharton termed “the chaos of indiscriminate appetites.”

The publication in 1895 of Ward McAllister’s Society as I Have Found It, a combination memoir and connoisseur’s guide, promised to tame the “chaos”—while ultimately infuriating the Four Hundred with its candor. McAllister’s reader could now learn that champagne ought to accompany a dinner from the fish course to the roast and that a vin ordinaire was acceptable throughout the numerous courses of the dinner. A Burgundy or Johannisberg or “fine old Tokay” complemented the cheese, and the roast was partnered with the “best claret.” Finally, “after the ladies have had their fruit and left the table,” the gentlemen were served “the king of wines, Madeira, . . . that imparts a vitality that no other wine can give.” McAllister promoted Madeira as if it were an elixir: “The next day you feel ten years younger and stronger for it.”

Madeira’s effect on youth and strength aside, McAllister breathlessly lists the best years for clarets and the “great” ones for champagne (the summa: 1884), his oenological credential proving his worthiness as Mrs. Astor’s longtime social chess master, sounding in places like a bossy sommelier: “In decanting, hold the decanter in your left hand, and let the wine first pour against the inside of the neck of the decanter. . . . Table sherries should be decanted and put in the refrigerator one hour before dinner.”

Among the Four Hundred, private cellars were a point of pride, as they are today. Edith Wharton relished her family’s reputation for its “celebrated” cellars that included her father’s “vintage clarets” and a Madeira that aged perfectly as it “rounded the Cape” on its slow voyage from Portugal. Ward McAllister, however, warned against amassing “a large cellar of wine,” cautioning that extended seasonal travels left servants “ample time to leisurely drink up the wine.” One such breach occurred in the Newport high season at “Crossways,” the home of Mrs. Stuyvesant (“Mamie”) Fish. Mrs. Fish’s autocratic English butler, Morton, had served, notably, in “English ducal families” and “could wither the most brazen offenders” of decorum with “one glance of superiority.” Throughout his aristocratic service, however, he had acquired “a fine taste in wines.” One afternoon, as Mrs. Fish’s twentieth luncheon guest arrived, an exasperated Morton “burst into the hall,” obviously under the influence, all constraints loosed. “I suppose because you happen to be Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish you think you can drive up and down the avenue inviting who you like to the house,” he ranted. “Well, let me tell you, you can’t.” He was dismissed the following day.

Though Society as I Have Found It reads like the manifesto of a latter-day wine snob, McAllister’s recipe for the champagne frappé, with its “little flakes of ice,” implies that the Gilded Age might also be known as the Golden Age of Cocktails. The word “cocktail” might visually suggest a rooster tail, but the custom of docking the tails of nonthoroughbred horses meant they were “cocktailed,” signifying that these animals were not purebreds. By the early 1800s, a spirit compounded with other ingredients, including water, was no longer purely itself. From the end of the Civil War, however, suspicions about dilution gave way to exhilaration as palates thrilled to the delights of new and newer libations being served in private homes. The etiquette adviser M. E. W. Sherwood’s Art of Entertaining (1892) suggested recipes for a dozen cocktails, claiming their heritage from the days of Cleopatra. House guests of Pembroke and Elisha Jones, such as Elizabeth and Harry Lehr, pronounced the couple “famous” for their “high balls and mint Julips.” After “several cocktails,” Mr. Lehr confessed, “I became strongly gay.” Hosts uncertain of their skills with the cocktail shaker could rely on the Heublein Company of Hartford, Connecticut, as of 1892. Its line of bottled Club Cocktails were premixed, requiring only ice and the proper stemware for a Manhattan, gin martini, or whiskey cocktail.

The designated “cocktail hour” of the Gilded Age varied according to desire or necessity. It might begin early in the day, the hour of the “hangover” when one needed the “hair of the dog that bit” the preceding night. A milk punch was called for at this early hour, as were “brain-dusters,” such as chilled absinthe or Black Velvets (equal portions of porter and champagne). A late-morning beverage was a welcome prequel to lunch, such as the mint juleps “dispensed every morning before luncheon to a select little coterie of the younger set” at the Newport summer home of the Pembroke Joneses. “As regards midday beverages,” Mr. H. Panmure Gordon recalled that “one’s brain reels at fond memories of Manhattan cocktails, Remsen refreshers, gin fizzes, the most subtle and captivating, and hundreds of others.” These hundreds might include drinks to celebrate historic milestones: the Coronation for King Edward VII, the Santiago for Admiral George Dewey’s victory in the Spanish-American War, the Dr. Cook for Frederick Cook, the surgeon on Robert Peary’s arctic expeditions from 1891 to 1892.

Crafted mixed drinks were soon passed liberally across the mahogany bars of men’s clubs, sumptuous restaurants, and fine hotels such as the Hoffman House and the Waldorf-Astoria. Celebrity bartenders were the wizards, the very names of their secret delectations as alluring as they were mysterious—the Shandygaff, Sitting Bull Fizz, Gin Sangaree, Whiskey Sling, Lightning Smash, and so on. Occasionally the provenance of a name could be determined. In one instance, a customer dared the master bartender Johnny Solon of the Waldorf to devise a new cocktail on the instant. Witnesses to the event were plentiful, for the establishment was a favorite of Wall Street businessmen and dandies who lined a bar bracketed at its ends by a bronze bear and a raging bull—with a wee lamb in between. Silver shaker in hand, Maestro Solon accepted the challenge, compounding a gin martini with orange bitters and adding dashes of vermouth. Solon had recently visited the Bronx Zoo: voilà, the Bronx!

For the most part, however, the origins of popular Gilded Age cocktails are lost. Consider the Morning Glory, one of numerous compounds in the repertoire of a “professor” behind the bar:

- 3 dashes gum syrup

- 2 dashes curacao

- 2 dashes bitters

- 1 dash absinthe

- 1 pony each brandy and whiskey

- Twist of lemon

- Ice

Stir, strain, and top with soda, then stir with teaspoon that has sugar in it.

By all accounts, the master mixologist was Jerry P. Thomas. Born in upstate New York near the Canadian border in 1830, he honed his craft well before the Gilded Age in knockabout years as a sailor, gold miner, and gambler—all the while tending bar from Connecticut to London, England, to San Francisco and the silver-mining boomtown of Nevada’s Virginia City. He served a stint at the New York bar of P. T. Barnum’s museum and, ever restless, apprenticed in saloons in St. Louis and New Orleans before looping back to Gotham. Dubbed by an admirer of 1863 as the “Jupiter Olympus of the bar,” Thomas cut a glittering figure as a “gentleman who is all ablaze with diamonds,” the “front of his magnificent shirt” boasting a “very large pin formed of a cluster of diamonds.” At his wrists were “diamond studs,” and his fingers flashed with “gorgeous diamond rings,” “‘properties’ essential to the calling of a bar-tender in the United States.”

Celebrity bartenders closely held the secrets of their signature cocktails. Authorship, however, proved tempting, and 1862 saw the first edition of his How to Mix Drinks, listing recipes for just ten straightforwardly named cocktails: Bottle, Brandy, Fancy Brandy, Whiskey, Champagne, Gin, Fancy Gin, Japanese, Soda, and Jersey. A later edition in 1877, now subtitled The Bon-Vivant’s Companion, added another 130 drinks with such names as the Deadbeat, the Moral Suasion, and the Fiscal Agent. The preface to The Bon-Vivant’s Companion offered moralistic pieties that offset the alcoholic license of the myriad drinks that followed. “We do not propose to persuade any man to drink,” wrote Thomas (or his prudent editor). “We simply contend that a relish for ‘social drinks’ is universal, and . . . that he who proposes to impart to these drinks . . . is a genuine public benefactor.”

Thomas’s best-known drink was the Blue Blazer, a mix of scotch whisky and water. “Use two large silver-plated mugs with handles,” he instructed, and then prepare “1 wine-glass of Scotch whisky, 1 of boiling water.” “Put the whisky and the boiling water in one mug, ignite the liquid with fire, and while blazing . . . pour them four or five times from one mug to the other.” “If done well,” he promised, “this will have the appearance of a continued stream of liquid fire.” This was more than a simple scotch and water. It was a seasonally wintry affair, a theatrical pyrotechnical display that awed all within sight. When the fire died, advised Thomas, “sweeten with one teaspoonful of pulverized white sugar, and serve in a small bar tumbler with a piece of lemon peel.”

Though a young lady of the Four Hundred seen sipping a glass of champagne in public became a titillating item of Town Talk or other newspaper gossip, the champagne fairly gushed at private balls and dinners. Edith Wharton frowned on the “nouveau riche” whose taste ran to “champagne and claret,” but Elizabeth Lehr marveled at “dinner tables laid for a hundred and fifty guests, . . . vintage wines, nothing but the choicest champagne.” Her husband, Harry, remarked on “caviar” and “the most expensive wines” at evening balls when “champagne may flow like water.” The typical tally of champagne and other rare vintages at the balls and other Gilded Age fetes is not a matter of public record, but one social observer, Albert Stevens Crockett, somehow got hold of the inventory of the Bradley Martins’ expenditures for their famous—or infamous—ball of February 10, 1897, at the Waldorf Hotel, which he declared to be a great bargain:

- Ballroom and Supper—700 — $4,550.00

- 59-10/12 cases Moet & Chandon @ $50 a case — 2,991.70

- 4 bottles Irroy Brut @ $3.50 — 14.00

- 10 bottles Moet & Chandon WS @ $3.50 — 35.00

- 55 bottles Château Mouton @ $2.25 — 123.75

- 6 Medoc Superieur @ $.75 — 4.50

- 496 bottles Mineral Water @ $.30 — 148.80

- 11 bottles Whiskey — 22.00

- 3 bottles Brandy — 18.00

- 48 bottles Soda — 7.20

- Beer and wine for musicians — 43.50

- Victor Herbert’s band — 658.00

- Carl Berger’s and Eden Musée bands — 250.00

- Supper and cigars (probably including food for musicians and policemen) — 150.00

- Ribbons — 20.00

- Total — $9,036.35

“Only a little over nine thousand dollars for the . . . most lavish” party of its day, Crockett exclaimed, adding, “the ‘Moet & Chandon’ drunk so liberally by Mrs. Bradley Martin’s guests was the rarest and most expensive sparkling wine known in the United States in 1897.” Perhaps so. It flowed as well at select restaurants, especially Delmonico’s, which imported European wines directly by the hundreds of cases, some under its own champagne label as the “Delmonico Brand.” As the New York Herald quipped, “As Delmonico’s goes, so goes the dining.” (The imbibing was assumed.) The Herald hailed the “fragrant wine” of this “palatial house.” The menu carte from the first Delmonico’s in the earliest years of the late 1830s had set the standard for the Gilded Age, with its half dozen different champagnes and another dozen vins blanc from the Rhone and the Rhine, plus twenty Bordeaux Rouge on a descending scale from the rare Lafitte to the ordinaire. Liqueurs abounded, whether one preferred extrait d’absinthe or crème de chocolat.

The gale-force winds of the temperance movement could not be completely ignored by the Four Hundred and their outer social circles. The vintner, the distiller, and the brewer all felt the gusts. Throughout the 1800s, the movement to ban alcoholic beverages had gained strength, and later 1800s organizations such as the Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) pressed elected officials to pass laws banning alcohol. Ministers inveighed against it from the pulpit, and church women knelt to pray at saloon doors, beseeching the Lord to protect families from the devil’s brews that ruined families. They testified that bread winners’ wages disappeared into saloons before reaching their homes, leaving wives and children destitute. The WTCU and allied groups contended that the health and well-being of the American family depended on the legislative elimination of alcohol. Prohibition was on the horizon. Well aware of the trend, the hospitality industry prepared to open private clubs and “speakeasies.” The Four Hundred, for their part, arranged for shipments to guarantee that libations would flow in private homes without interruption.